Coaching Will Be The Last Human Job

Sam Altman and Arianna Huffington plan to make an AI health coach, which will address chronic illness by encouraging people to eat better, take their medications, and get more sleep and exercise.

Consider what it’s like to be a busy professional with diabetes. You might be struggling to manage your blood-sugar levels, often missing meals and exercise due to a hectic schedule. A personalized AI health coach, trained on your medical data and daily routines, could provide timely reminders to take your medication, suggest quick and healthy meal options, and encourage you to take short breaks for exercise.

A busy professional might benefit from an AI coach, but as Ben Krauss points out, it’s the working class who suffer most from chronic disease, and have the highest obstacles to a healthy lifestyle.

I want to criticize a different aspect of this pitch:

Yes, behavior change is hard. But through hyper-personalization, it’s also something that AI is uniquely positioned to solve.

Behavior change is something that a human coach is uniquely positioned to solve. No matter how smart, a mechanical coach’s impact is limited by my ability to ignore it. I’ve set myself all sorts of digital reminders and nudges and I routinely tell them to piss off. My employer nags me with automated messages about various policies, I delete them reflexively. So long as I know my nagger isn’t human, I feel no obligation to respect it.

I have at various times hired a personal trainer, a couples therapist, and a climbing mentor. In all cases, I granted my coach the authority to nudge me to do something. I had some long-term goal (fitness, an honest relationship, courageous climbing), but I was hampered by my short-term laziness or fear. I used my coach’s authority or charisma or whatever as extra oomph to overcome my reluctance. AI could one day match any coach’s expertise and personalization, but I doubt it will replace a human coach’s ability to exert peer pressure. Only a human can do that, because only a human is my peer. AI will either be my servant or, if it isn’t, then AI will no longer care about sharing recipes with me, it will be too busy converting me to paperclips.

Here’s a recent example of peer pressure. My climbing mentor Dustin Portzline was belaying and coaching me while I was scared on a climb. I repeatedly approached the crux, hesitated, and climbed back down to a ledge. I couldn’t calm myself and I started to give up. I asked Dustin to pull the rope tight so I could hang from it—if he had, I would have ruined my chance to claim a clean ascent. Dustin said, “I can do that, but are you sure? Do you want to try one more time?” His calmness and encouragement helped me collect myself. I respect him and I wanted to do my best for him. I tried once more. As I approached the crux and hesitated again, Dustin yelled up, “Increase the tempo!” …that’s what I remember. He says he yelled, “Move faster!” I was kind of blacked-out with fear, half-animal, but I stand by my recollection. Anyway, his instruction was the extra motivation I needed. I lunged for the next hold and latched it, and finished the climb.

Here’s Dustin’s version of events:

I experience from humans an “aura” which shines from no mechanical reproduction of humanity. Being face-to-face with another human has the most powerful effect on us, but even a text message from a human demands our consideration in the way an automated text doesn’t. If I respect someone, then I care what they think of me and I don’t want to disappoint them; I’ll try harder. My personal trainer made me stronger partly by prescribing the right exercises, and partly by watching me and yelling, “C’mon! One more!”

In fact the content of another person’s advice is less important than their attention. Therapists sometimes offer insight, but they mostly listen as their patients discover themselves. Factory workers are more productive when a researcher dims the lights, or makes them brighter—the brightness doesn’t matter, the workers are more motivated because they know a researcher is paying attention to them.

Of course, human coaches are very expensive, and Baumol’s cost disease makes them more so. If Altman and Huffington’s AI coach is cheaper than a human, then it’s worth a try, even though it won’t be as effective. But in the long term I expect Baumol’s cost disease to reverse: robots will do most of the work, and there will be a surplus of human labor looking for jobs. They will collect in the professions where the human aura is important or essential: therapists, stage actors, judges, nannies, masseuses, butlers, prostitutes, coaches.

There may be AI-native generations in the future that respect machines as much as they respect people. The special aura of humanity will be gone for them. A machine’s attention, although divided among millions of users, will be as satisfying to them as the undivided attention of a human. Confessing their shame to a machine will be just as great a relief. A robot yelling “one more!” will be just as motivating. An AI judge’s decision will carry the same weight. Good luck to them, I can’t imagine their lives. For a while, though, I think that coaching will be among the last essentially human jobs.

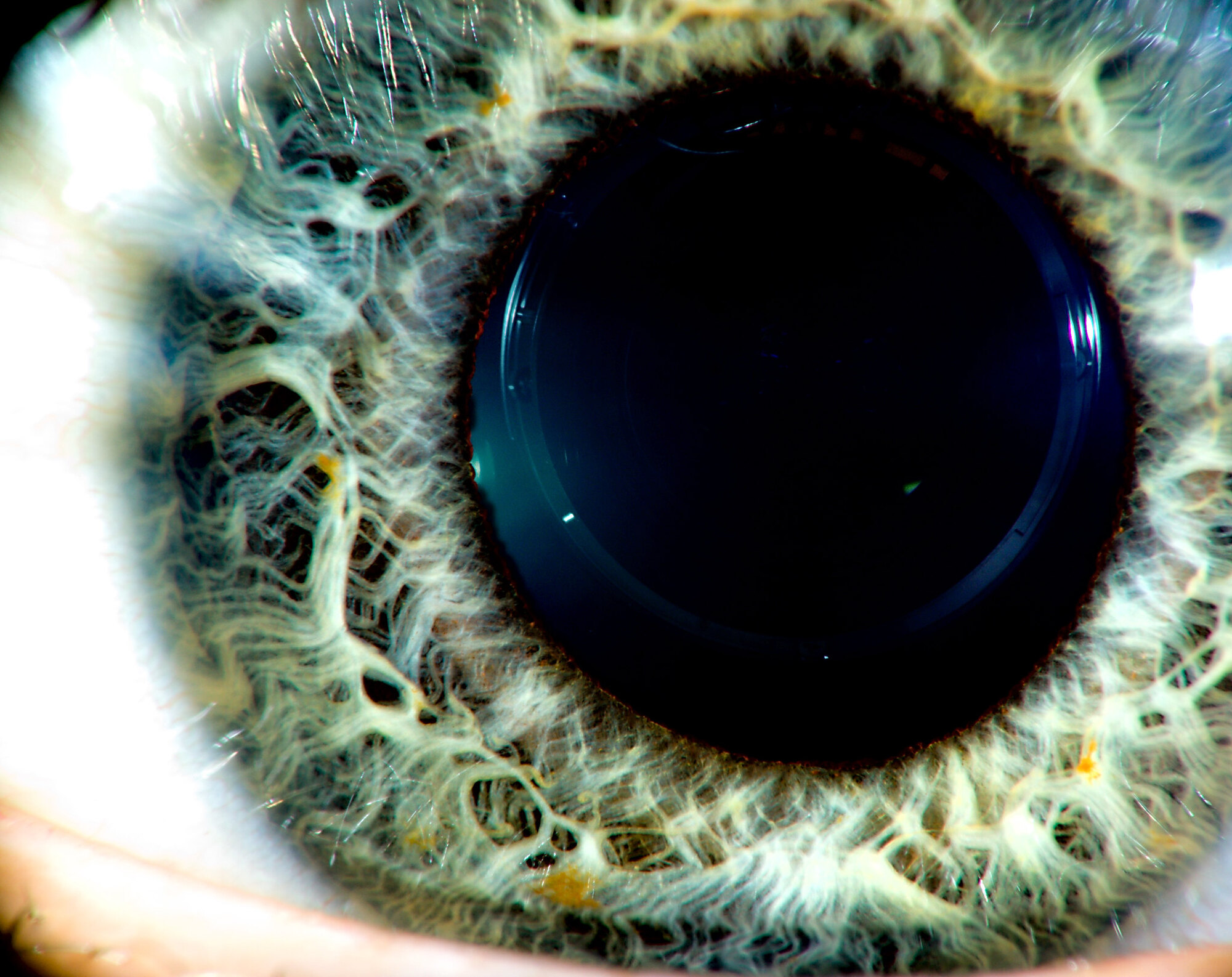

Photo: my eye.