Paper review: Strong and Efficient Consistency with Consistency-Aware Durability

Strong and Efficient Consistency with Consistency-Aware Durability, by Aishwarya Ganesan, Ramnatthan Alagappan, Andrea Arpaci-Dusseau, and Remzi Arpaci-Dusseau, FAST (the USENIX conference on file and storage technologies) 2020.

In leader-based consensus protocols like Raft, Paxos, or ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast (“ZAB”), clients typically write some data, then wait for a majority of servers to replicate the write and make it locally durable, to ensure the write will survive the loss of any minority of servers. This paper makes an eccentric proposal: clients can write without waiting, then wait for durability before reading. This doesn’t prevent data loss, but it does guarantee that clients never read data that is lost subsequently. Add a further guarantee that the system replies to each query with data at least as fresh as its previous reply, no matter which client is querying it, and you get a quirky new consistency property: “cross-client monotonic reads”.

The paper makes four claims:

- “Cross-client monotonic reads” is a novel and strong consistency property.

- It’s weaker than linearizability but still useful to applications.

- It’s more performant than linearizability.

- The system proposed, Consistency-Aware Durability or “CAD”, guarantees cross-client monotonic reads.

With cross-client monotonic reads, the system can still reply with stale values. So, read-your-writes is not guaranteed, much less linearizability. But, unlike with session guarantees, this property does not require you to use the same client for a series of reads.

Guaranteeing monotonicity with the durable index #

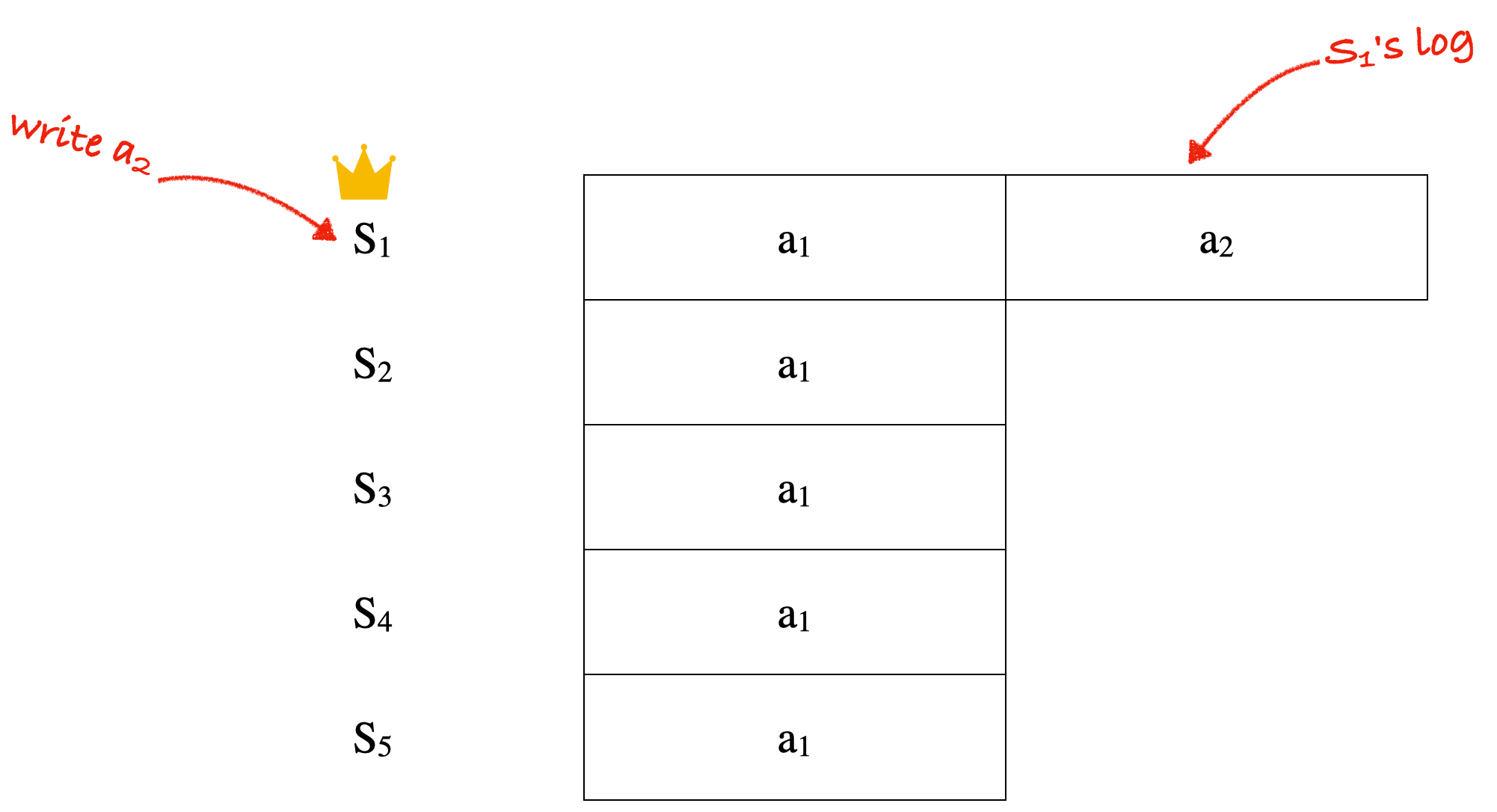

How does CAD guarantee this property? Let’s take an example with 5 servers. CAD works with leader-based protocols—in the paper they have extended ZAB, but I see no reason it couldn’t apply to Raft or Paxos—so let’s say that server S1 is the leader and the others are followers. Suppose the client writes the value “a1” to the key “a” (ZooKeeper is a key-value store). It sends its write to S1, and S1 appends the write to its log, as in most consensus protocols. S1 applies the write to its local data immediately, unlike with Raft or Paxos. S1 eventually replicates the write to its followers. Then the client writes “a2” to the key “a”, but this write hasn’t been replicated yet.

Now S1’s value for “a” is “a2”, and it has two log entries. Its followers’ value for “a” is still “a1” and they have one entry.

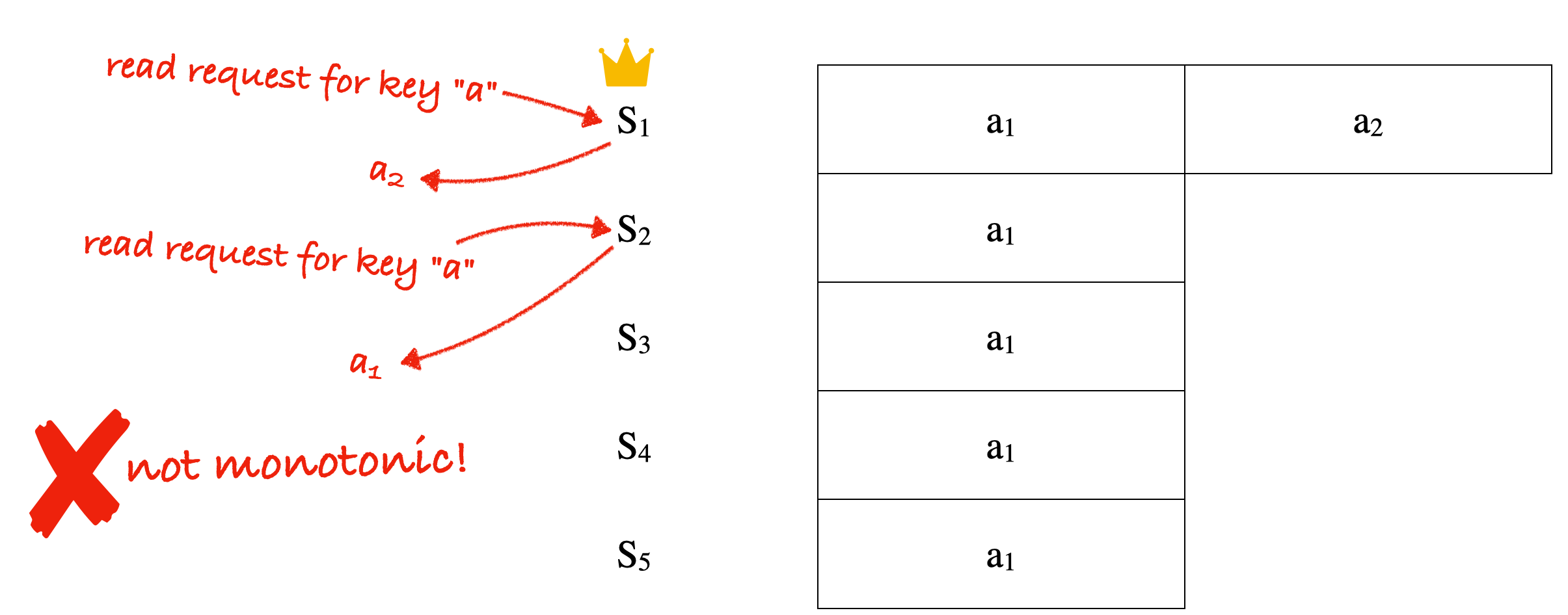

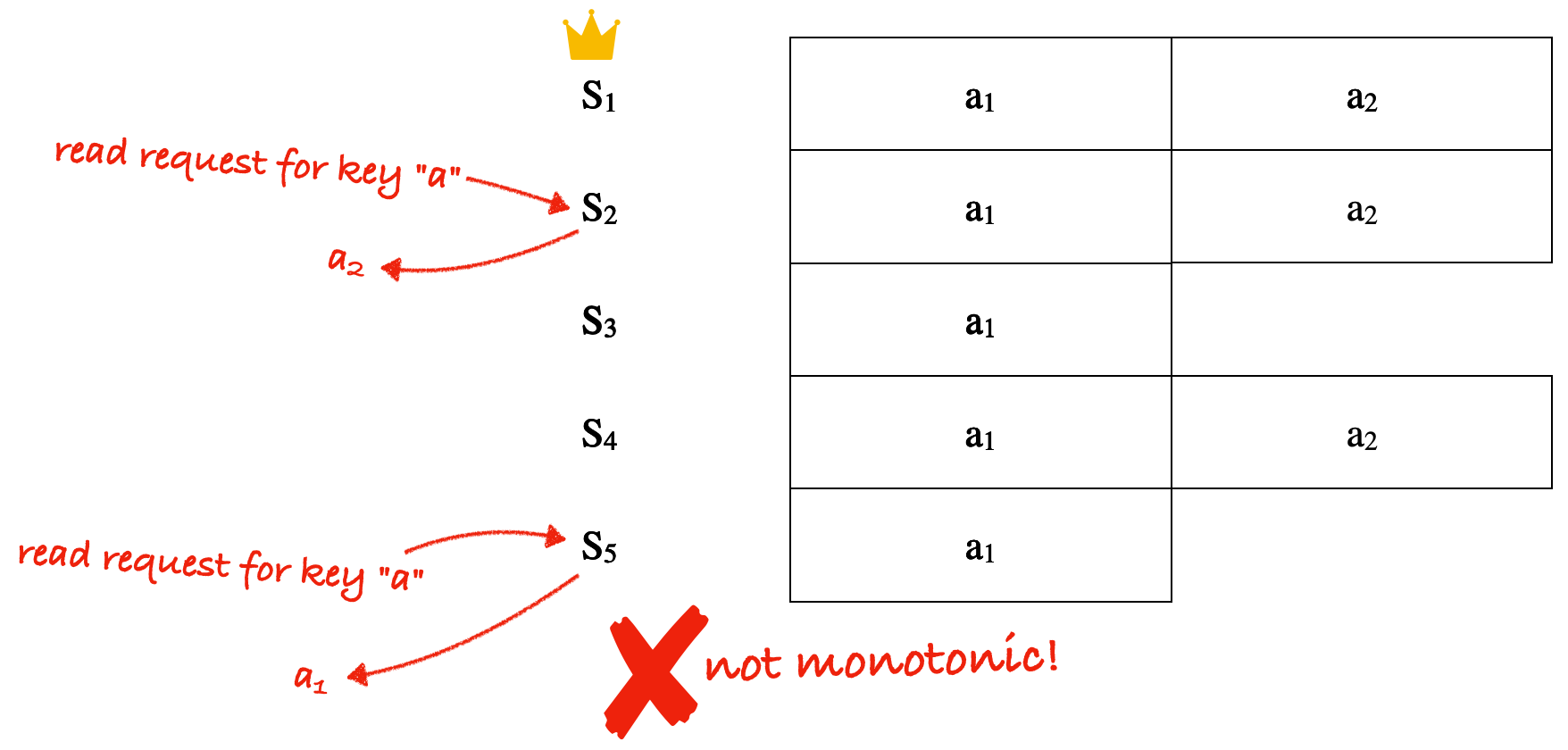

The important question now is, what reads are permitted without violating monotonicity? If the client reads first from S1, then a follower such as S2, it would see “a2” then “a1”, which is wrong.

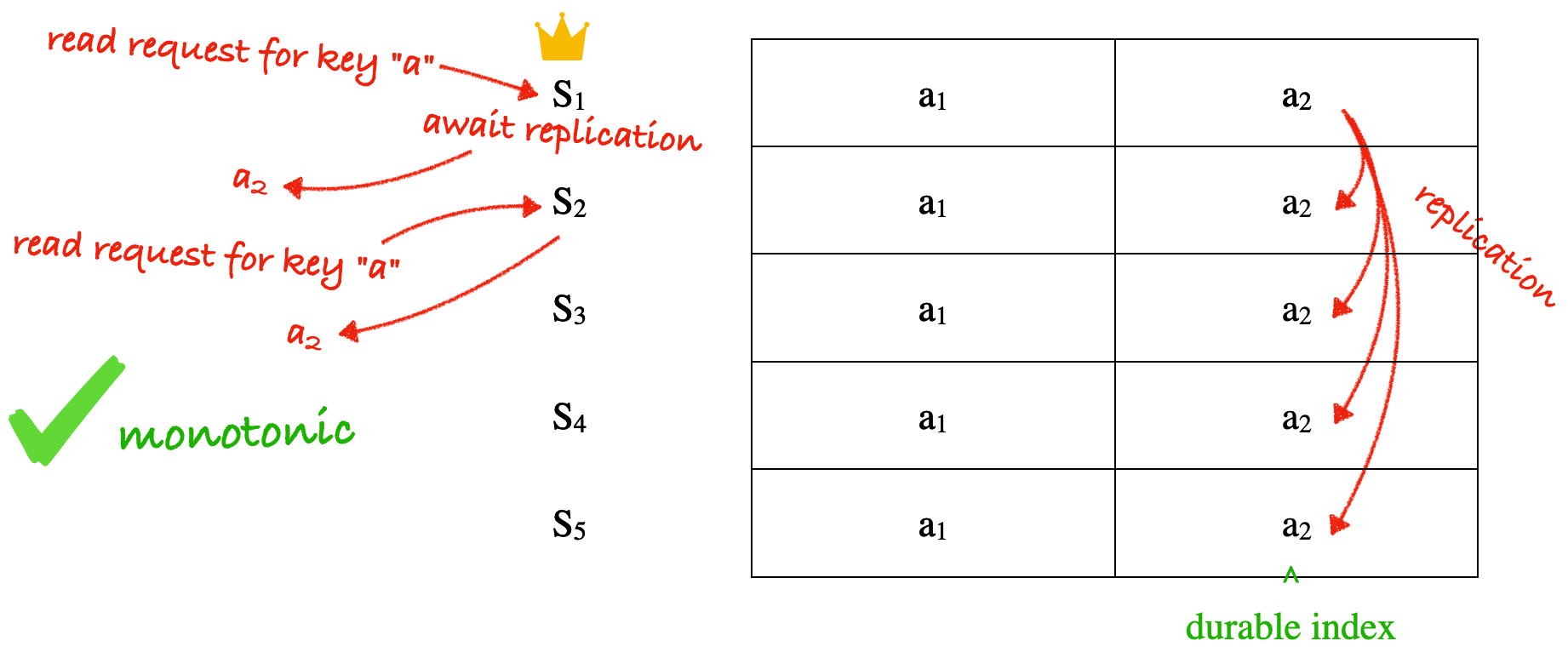

In CAD, the leader tracks how recently each key has been updated. It also tracks how recently all the followers have replicated updates: this is the “durable index”.

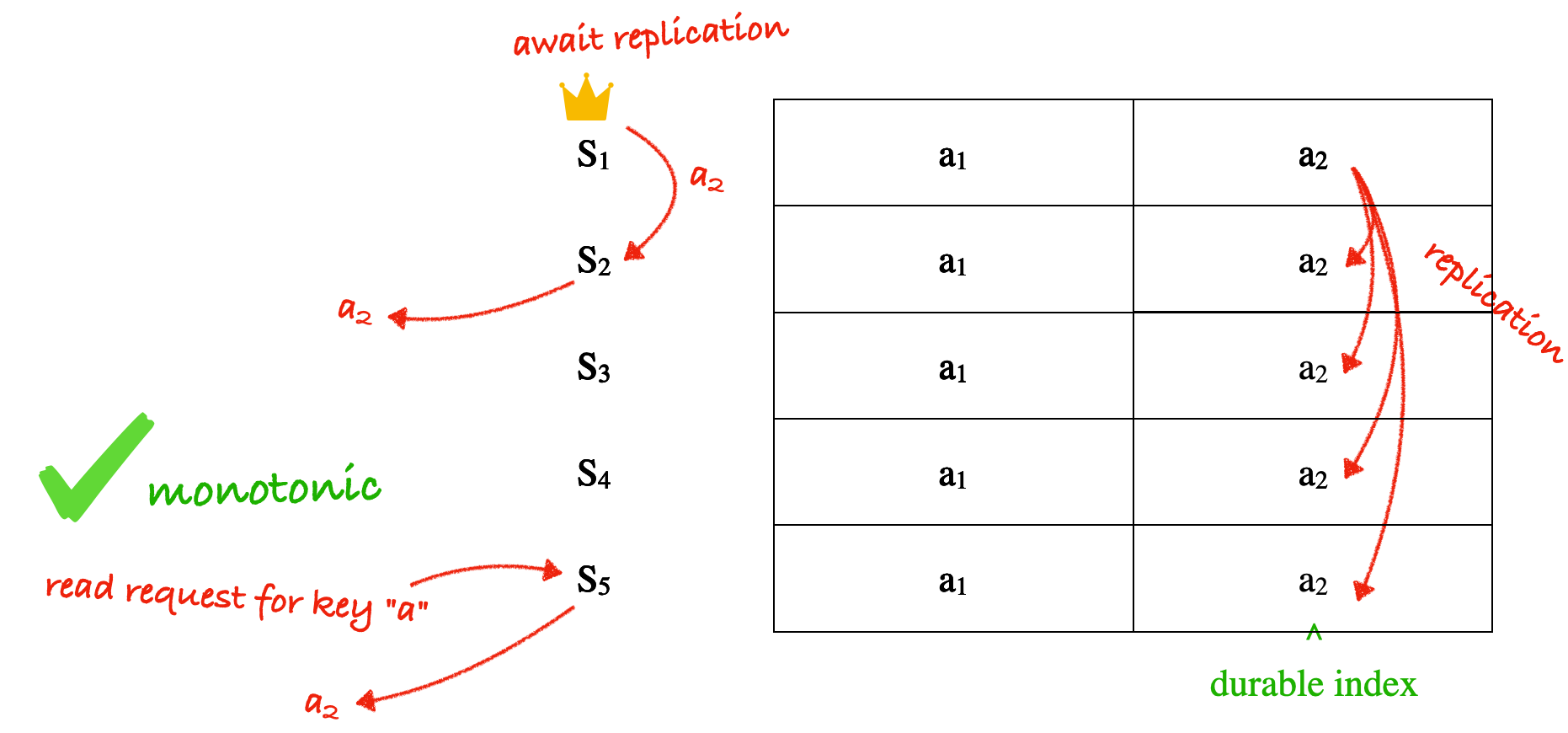

When the leader receives a request for key “a”, but the followers haven’t replicated the latest write to “a”, that means the durable index is stale. The leader waits for followers to all replicate, and it advances the durable index, before it answers the request with “a2”. That means any later request, from any client on any follower, will also get “a2”. The followers’ replies are at least as fresh as the leader’s, thus they’re monotonic.

(By the way I’m showing diagrams as if there’s only one key in the system. In fact, the system is tracking when each value was most recently updated, by tracking the log index of its last update.)

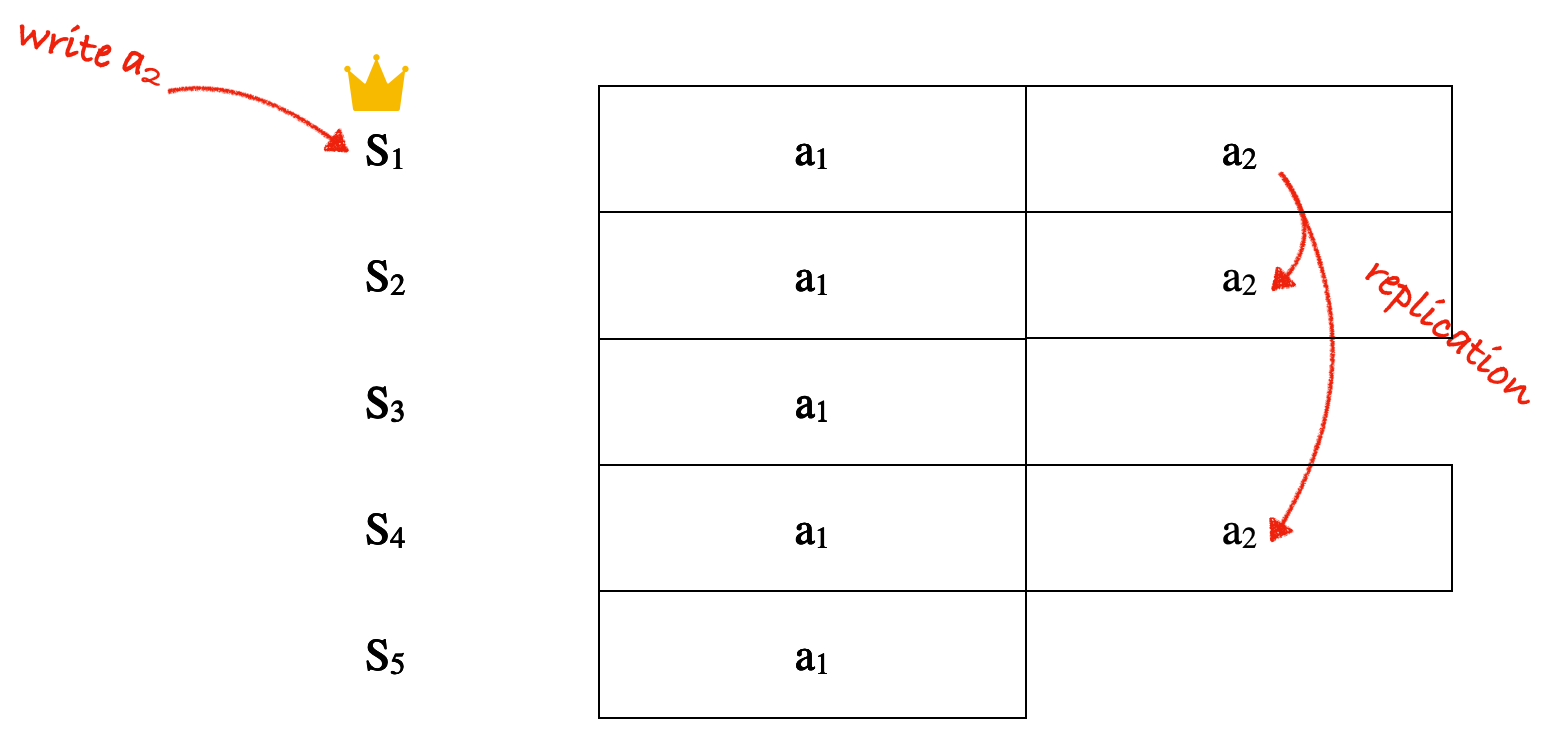

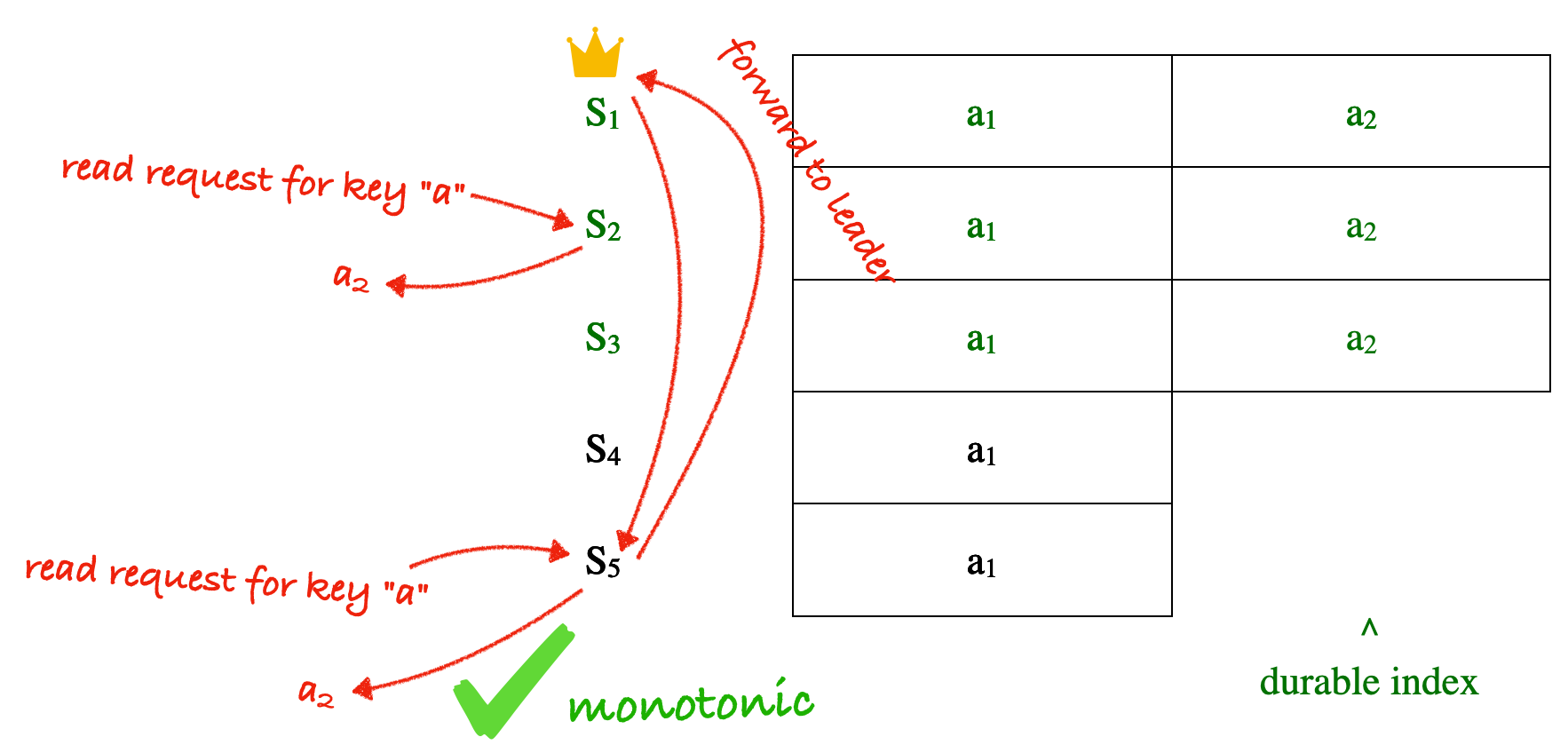

So, that’s how CAD makes a follower read, after a leader read, monotonic. What about two follower reads in a row? Suppose again that a client writes “a2” to the leader, and it replicates to followers S2 and S4, but the other followers haven’t replicated yet.

Now, if all followers were allowed to serve reads without waiting, the client could read “a2” from S2, then the older value “a1” from S5, violating monotonicity.

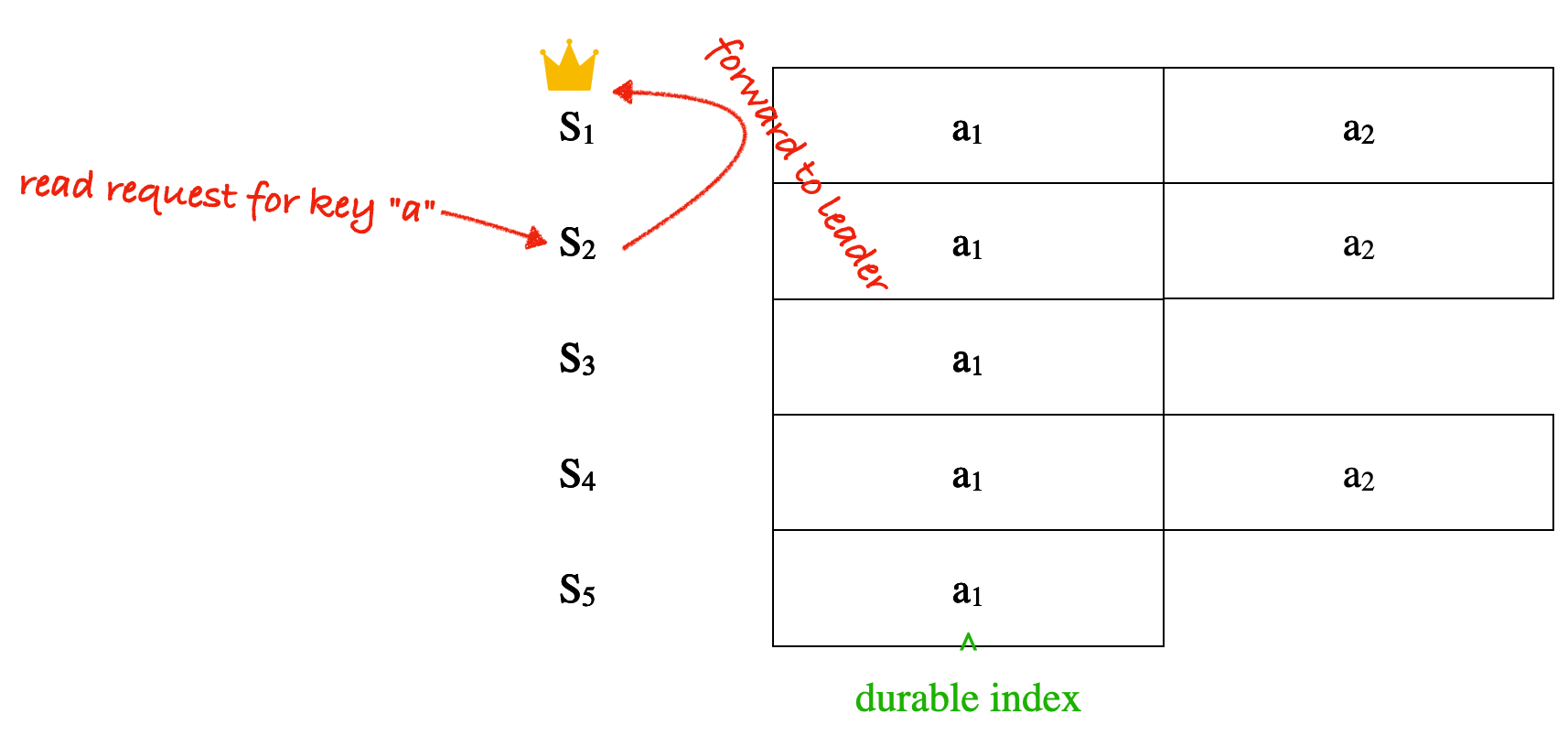

Let’s see how the durable index guarantees monotonicity when reading from two followers. When the client has written “a2” to the leader, and only two followers have replicated it, the durable index is still on the previous value “a1”. The durable index is not updated when a majority replicates a log entry (unlike most consensus systems), only when all of them have. When S2 serves a read for a key that’s been updated more recently than the durable index—in this case, key “a” was updated in the second log entry, but the durable index is still on the first entry—the follower forwards the read to the leader.

Now the leader behaves just like we saw before: when it serves a read for a key that was updated more recently than the durable index, it waits for all nodes to replicate so it can advance the durable index, then it answers. The follower S2 relays the leader’s answer back to the client.

My interpretation is that the system presents a snapshot of the data at the durable index. Since the index only moves forward, reads are monotonic. How does the system always serve data at the durable index? First, any read of a key’s version after the durable index awaits an advance of the durable index. Second, any follower read of a key’s version before the durable index also awaits an advance of the durable index, so it can reply with the version at the durable index.

Avoiding blocking with the active set #

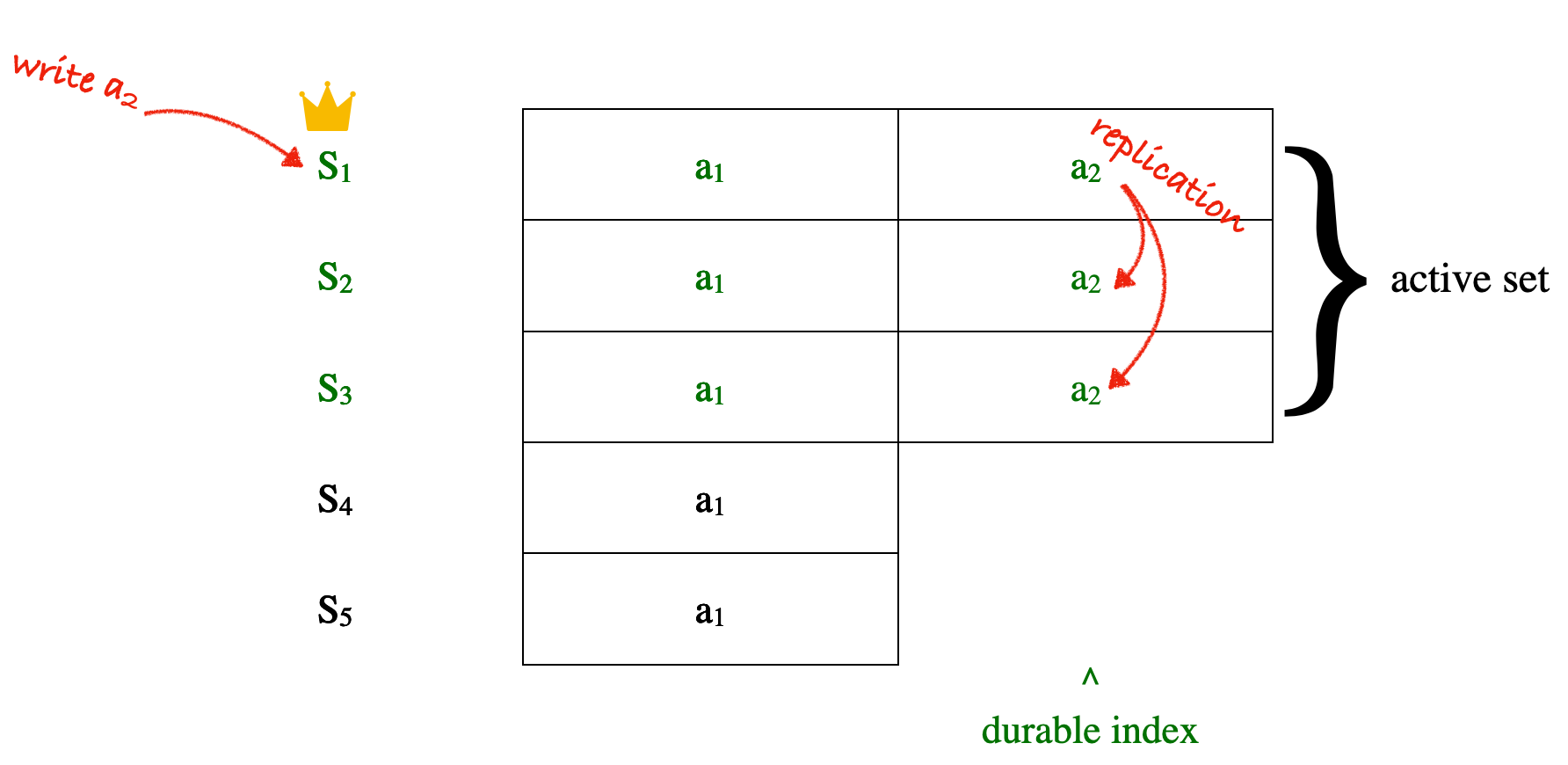

So far, I’ve said that the durable index is advanced only when all followers replicate a log entry. Obviously this is vulnerable to blocking: if one follower is laggy or down, the durable index is stuck. Read requests for keys updated more recently than the durable index will block until the follower recovers. CAD solves this problem with an “active set” of servers. The active set has to be at least a majority, but it can exclude unhealthy, laggy nodes. The leader advances the durable index as soon as a log entry is replicated by the active set, rather than waiting for all followers. Followers that aren’t in the active set can’t serve reads. (The paper doesn’t say how; I assume they forward reads to the leader.)

Suppose servers S1, S2, and S3 are in the active set, and the other two aren’t. If the client writes “a2” to the leader and at least S2 and S3 replicate it, then the durable index advances.

The active set is maintained with leases, and there’s some careful discussion about clocks and timing to ensure a member knows that it’s out of the active set before the leader knows, which is important for monotonic reads.

Now, a read from S2 can be answered without waiting: the durable index has advanced to include “a2”, even though the two laggy nodes haven’t caught up. A read from S5 is forwarded to the leader (I assume), which can answer without waiting for the same reason.

Their claims #

Let’s recall the paper’s claims and see if they’re justified.

- “Cross-client monotonic reads” is a novel and strong consistency property.

It’s certainly novel to me, but I quibble with the claim that a consistency property is “strong” if it doesn’t even provide read-your-writes. Maybe there’s a well-known definition of “strong” that I don’t know.

- Cross-client monotonic reads is weaker than linearizability but still useful to applications.

I’m very skeptical about its usefulness. If you can’t read your writes, do you care about consistency at all? Perhaps you’d prefer even weaker consistency in exchange for completely wait-free reads. The paper offers two examples of applications that might benefit from cross-client monotonic reads, but I find them a bit contrived. In both cases I think an application-specific solution would easy to implement. Apps that need only monotonic reads seem so niche, I’m not convinced a general solution would be marketable.

I had wondered if this is a better example: one application is write-only, and it updates the data in the proper order to preserve foreign-key constraints. Another application is read-only, and relies on monotonicity (it sees changes in the order they were written) to guarantee it never sees foreign-key violations. I thought this seemed like a plausible use case for monotonic reads, but then I remembered that CAD can lose writes, since writes don’t wait for durability, so the writer application can’t guarantee foreign-key constraints after all. (The paper mentions that their system provides a durable-writes option, but then the performance advantage is partly lost.)

To be fair to CAD, my objection is to monotonic reads as a consistency level in general. Providing cross-client monotonic reads is an improvement; I’ll say more below.

- Cross-client monotonic reads is more performant than linearizability.

Yes, writes are faster (but unreliable). Reads are faster if you don’t usually read the most recently-written data, so the system relies on certain access patterns. If you constantly read data just after writing it, then performance degrades to that of a linearizable system, as the authors show in their evaluation section.

- Their system guarantees cross-client monotonic reads.

Yes, a follower redirects reads to the leader if the follower is not in the active set, or doesn’t have the latest durable version of a value. The leader never returns a value that can be rolled back.

Their conclusion #

“Cross-client monotonic reads, a strong consistency guarantee, can be realized efficiently upon CAD. While enabling stronger consistency, CAD may not be suitable for a few applications that cannot tolerate any data loss. However, it offers a new, useful middle ground for many systems that currently use asynchronous durability to realize stronger semantics without compromising on performance.”

My conclusion #

If the “monotonic reads” consistency level is useful at all (a big if), then adding the “cross-client” guarantee is very helpful. In my experience, applications have trouble using session-based guarantees (which is how monotonicity is usually provided). A multi-tier application will generate a request near the top layer, and in a deeper layer it creates a database session and sends the request to the database. By the time the reply has bubbled back up to the top layer, the session is lost, and the next request can’t reuse it. So, guaranteeing monotonic reads to applications that don’t keep track of their sessions will make life easier for real-world programmers.

But any consistency level without read-your-writes is niche. If I were building a new distributed database, I’d want to provide users with a variety of choices of consistency level before I added cross-client monotonic reads: Linearizable, snapshot, eventually consistent, session-based causal consistency. Only then might I think it’s worthwhile to add this niche option. But if I did, CAD is a clever way to implement it, and I think it could be combined with other consistency levels.

Further reading: