Review: Cornus: Atomic Commit for a Cloud DBMS with Storage Disaggregation

Cornus: Atomic Commit for a Cloud DBMS with Storage Disaggregation, by Zhihan Guo, Xinyu Zeng, Kan Wu, Wuh-Chwen Hwang, Ziwei Ren, Xiangyao Yu, Mahesh Balakrishnan, and Philip A. Bernstein, at VLDB 2022.

This paper describes some optimizations to two-phase commit on top of cloud storage. If you’re using cloud storage and 2PC, this protocol will reduce commit latency and avoid 2PC’s dreaded “blocking problem”.

Table Of Contents

Background: Two-Phase Commit #

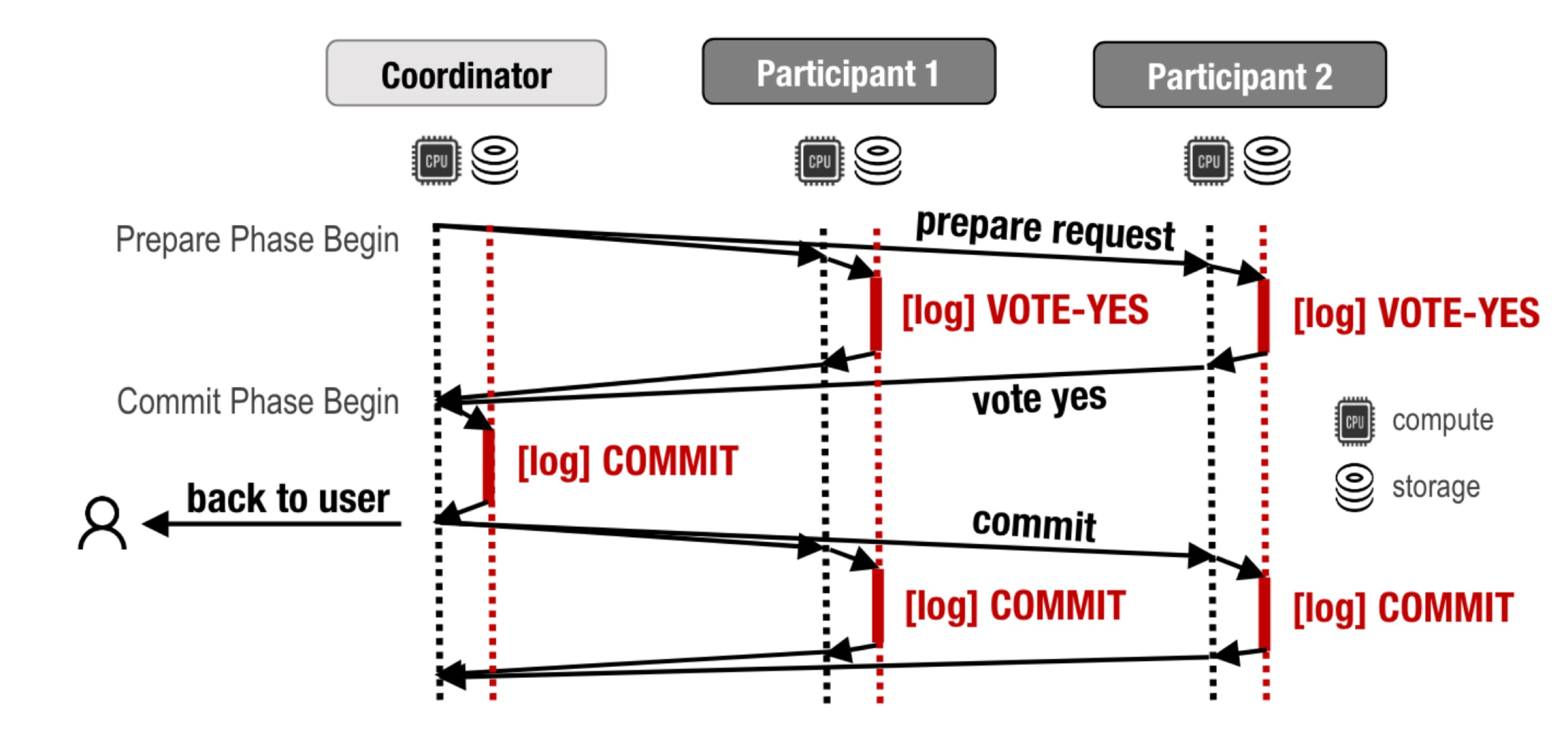

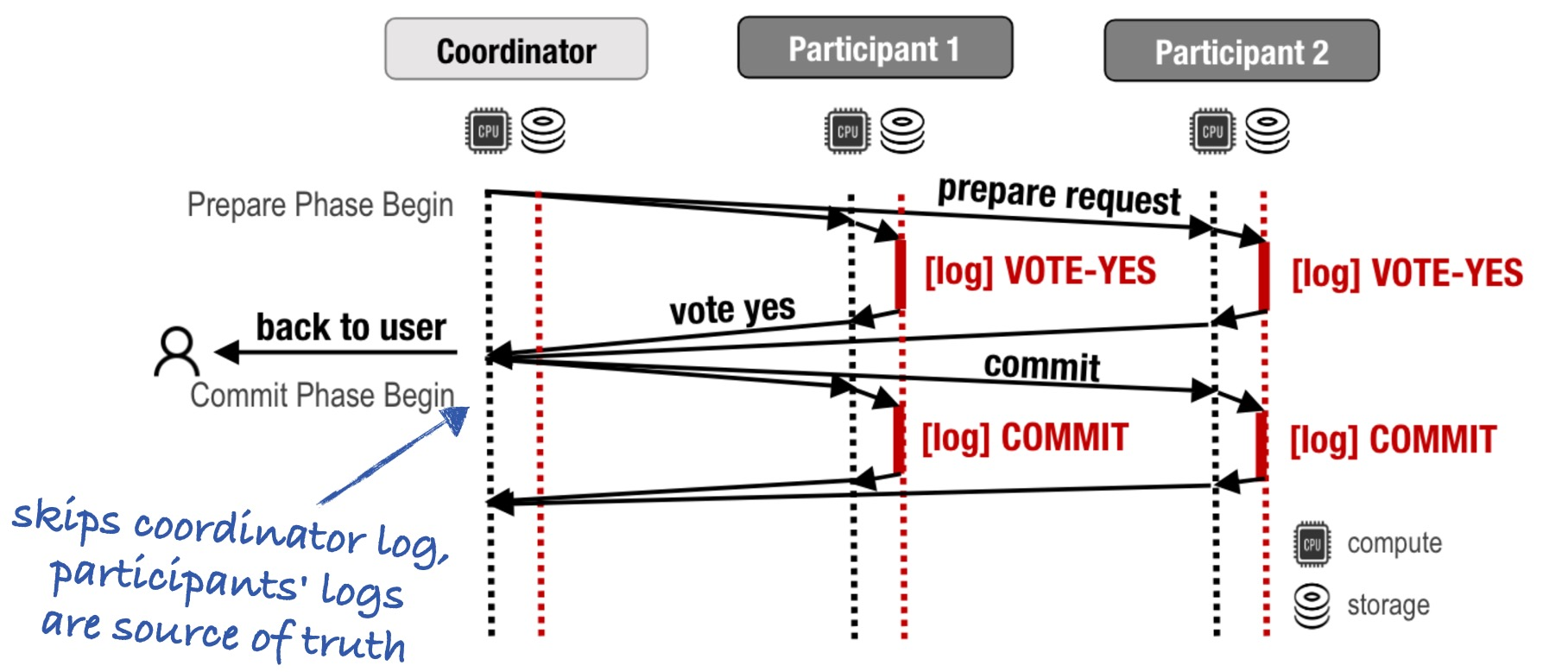

Let’s say we have a partitioned database. A user has started a transaction and written to several partitions, aka “participants” in the transaction. A coordinator has been chosen (maybe one of the participants, or a distinct service) and the user told it to commit. Now it must commit the transaction atomically: either all the transaction’s writes are made permanent, or none. The classic algorithm is two-phase commit (2PC):

First the coordinator sends a “prepare” message to all participants. They all log their votes to disk (they vote “yes” in this diagram) and reply. Once the coordinator hears all the yes-votes, or any no-votes, or times out, it logs its decision. It tells the client and participants about the commit decision. The participants log the decision.

The coordinator and the participants all have both compute and storage—those stacks of donuts are local disks.

Local hard disks.

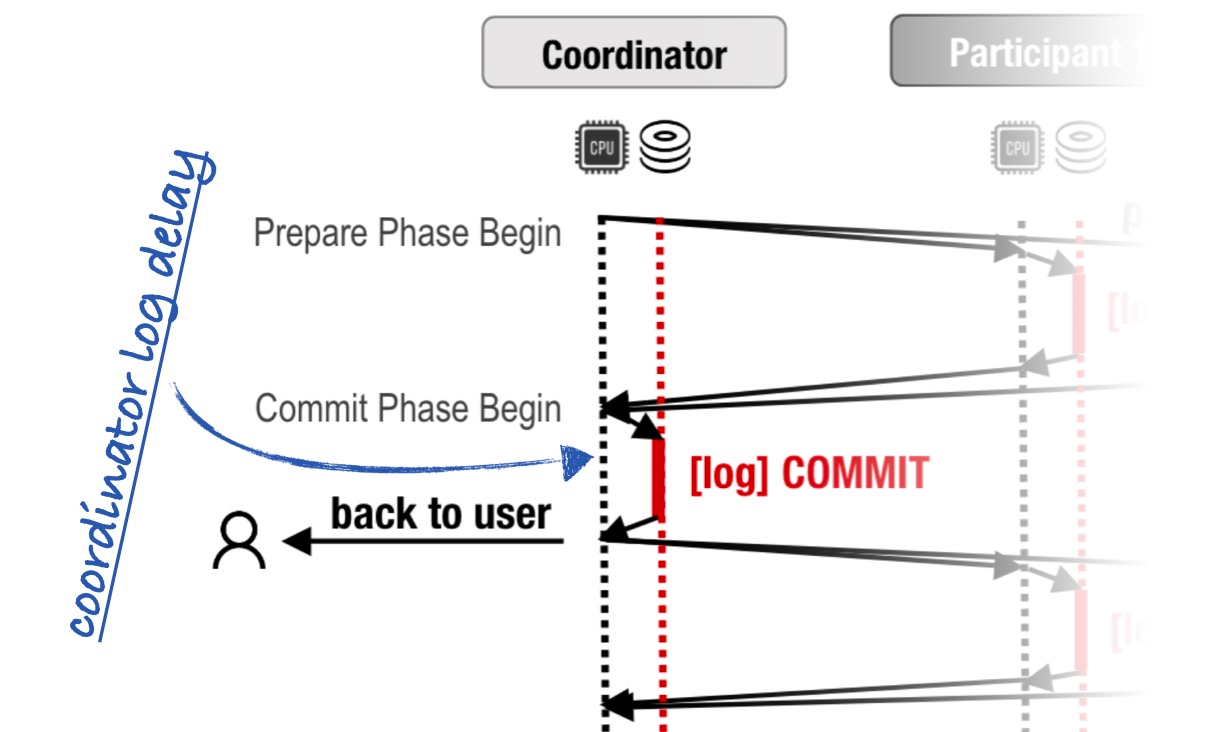

The coordinator must durably log its commit decision before it replies to the user. This causes some latency which we’ll call the coordinator log delay.

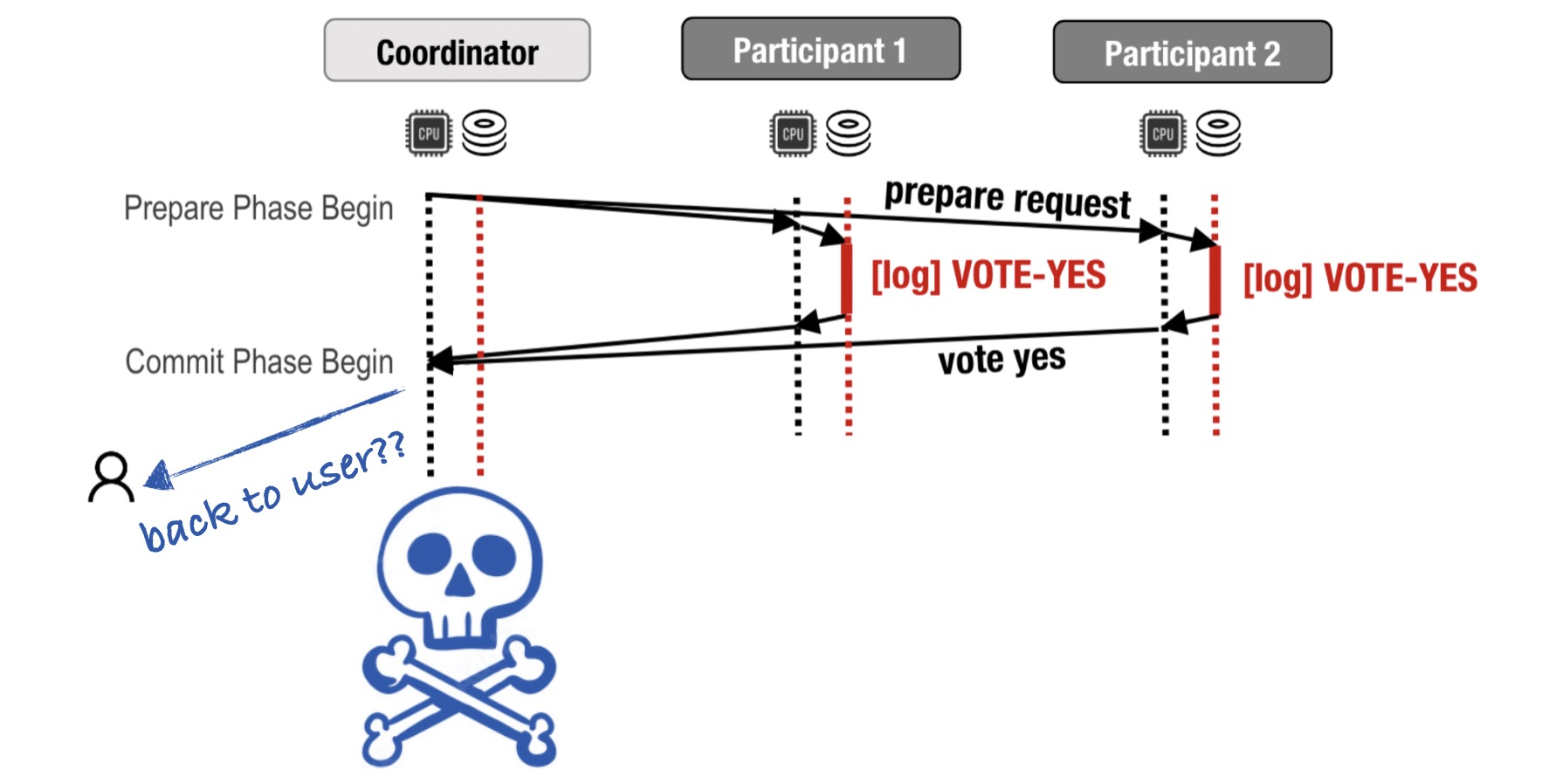

But why is this delay necessary? Let’s say instead that the coordinator just replies as soon as it decides. Well, what if it dies immediately after?

Now only the client knows the commit decision; none of the participants does.

Can’t we recover the decision by checking whether all the participants logged “yes”? No: if the coordinator timed out while waiting to hear all the votes, even if they were eventually all “yes”, then the coordinator would’ve aborted and told the user. But there’s no record of that decision in the system now. That’s why the coordinator must durably log its decision before it sends it to the user and the participants.

So if we lose the coordinator after it logs its decision, but before it has told the user and participants, then we can recover its decision when it reboots. But what if it never reboots? Participants must wait forever. This is called the blocking problem.

That’s 2PC. It’s been this way since the 80s. What’s new now? Now we have cloud storage.

Cloud Storage #

Cloud storage services (Amazon S3, Azure Table, Azure Blob, …) permit cloud databases to disaggregate compute from storage. Cornus is a 2PC variant optimized for cloud storage. It relies on a few features:

- Many cloud storage services have very high availability; lots of 9s.

- Since storage is on a separate layer from the participants, participants can read and write other participants’ logs!

- Writes to cloud storage are durable as soon as they’re acknowledged.

- Many cloud storage services permit something like compare-and-swap, which can be used to implement write-once.

Cornus can use any storage service, as long as these two APIs can be implemented on top of it:

Log(txn, message): A participant durably appends to its own log for txn. The message is a write operation.

LogOnce(txn, message) → message: A participant durably appends to any participant’s log with compare-and-swap. The message is VOTE-YES, COMMIT, or ABORT. If no such message exists for txn, update txn and return message. Otherwise, don’t update anything, return the already-existing message. This API is possible on top of S3, Azure Blob, etc.

The LogOnce API allows participants to write to each other’s logs concurrently. The first writer wins.

Cornus #

What if, instead of local disks, the coordinator and the participants all used cloud storage? In this figure from the paper, the stacks of donuts look the same as before, but now they mean cloud storage.

(Aside: the coordinator is stateless, it doesn’t log anything. So why does it have donuts?)

Cornus uses cloud storage to solve the blocking problem and to eliminate the coordinator log delay.

The 2PC blocking problem arises after a coordinator dies at an unlucky moment, because we don’t know if the coordinator made a decision, or what its decision was. In Cornus, though, the coordinator can’t decide anything—specifically it can’t decide to abort the transaction if it times out waiting for the participants. It must wait for the participants to all vote “yes” or any to vote “no”, then it relays this decision back to the participants, and to the user. The coordinator is stateless. If it dies, no information is lost. Once the participants give up waiting for the coordinator, they can recover the transaction state by asking each other how they voted. Since the coordinator doesn’t need to log anything, Cornus eliminates the coordinator log delay.

It’s ok if the coordinator replied to the user before it died: The participants will eventually figure out what it said.

This change makes sense if you bet the coordinator is more likely to die than any of the participants. But there’s one coordinator and many participants, so that seems like a foolish bet. But wait: if some participants die, that’s no problem! The surviving participants all use LogOnce to concurrently try writing ABORT to each others’ logs. (Remember, a participant’s storage is available even if the compute node died.) If all the logs already have VOTE-YES or COMMIT, then LogOnce returns those values and the surviving participants can commit. Otherwise they abort. Thus Cornus solves the blocking problem.

So cloud storage seems magical.

If you weren’t using cloud storage, then each database partition would need at least three-way replication for durability. Writes to cloud storage are also replicated for durability, but at a different layer. Thus they’re higher-latency than local writes: the authors say it’s ~10ms for Azure Blob in one data center, which is the minimum redundancy you’d want. So cloud storage isn’t magic, you’re paying the same latency cost in exchange for durability as if you implemented the replication yourself.

Their Evaluation #

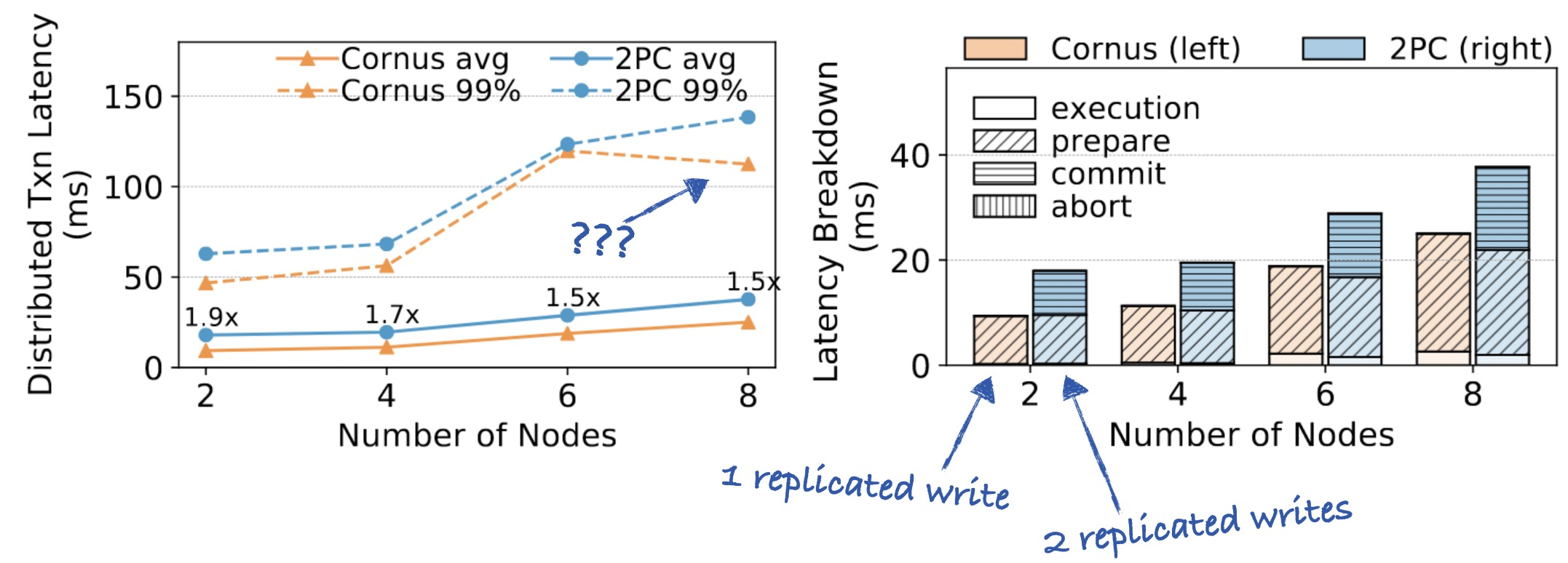

They have latency charts for Cornus implemented on top of several Azure services. I show Azure Blob because it’s the most like S3, which is what I’m most familiar with. I’d like to see Cornus actually implemented on S3, but the authors collaborated with Microsoft so they just used Azure.

Cornus latency with Azure Blob storage. I added the blue arrows.

Cornus clearly halves the commit delay from the user’s perspective. Cornus does one replicated write, and regular 2PC takes two, and replicated writes account for nearly all the latency.

(Why does p99 latency fall for Cornus with eight servers compared to six?)

My Evaluation #

This seems like a worthwhile improvement to 2PC on top of cloud storage. If you’re already using cloud storage for your distributed database, there are useful ideas here. I have four thoughts.

Thought One: The Storage Hierarchy #

Cornus works correctly so long as participants use the LogOnce API to write log messages directly to cloud storage whenever they vote, commit, or abort, but this incurs cloud storage’s latency for those writes. You might prefer participants write to a local cache instead, and asynchronously flush to cloud storage—this would be lower-latency but it won’t work with Cornus. Imagine that some participants think participant P is dead. They write ABORT to P’s log. If P is actually alive and has a local copy of its log, its copy will be inconsistent with cloud storage, and the participants will disagree about the transaction’s outcome.

So it’s essential in Cornus for LogOnce to write directly to cloud storage; this might make Cornus higher latency in total than a protocol that writes asynchronously to the cloud. The tradeoffs will be specific to your system’s architecture and usage.

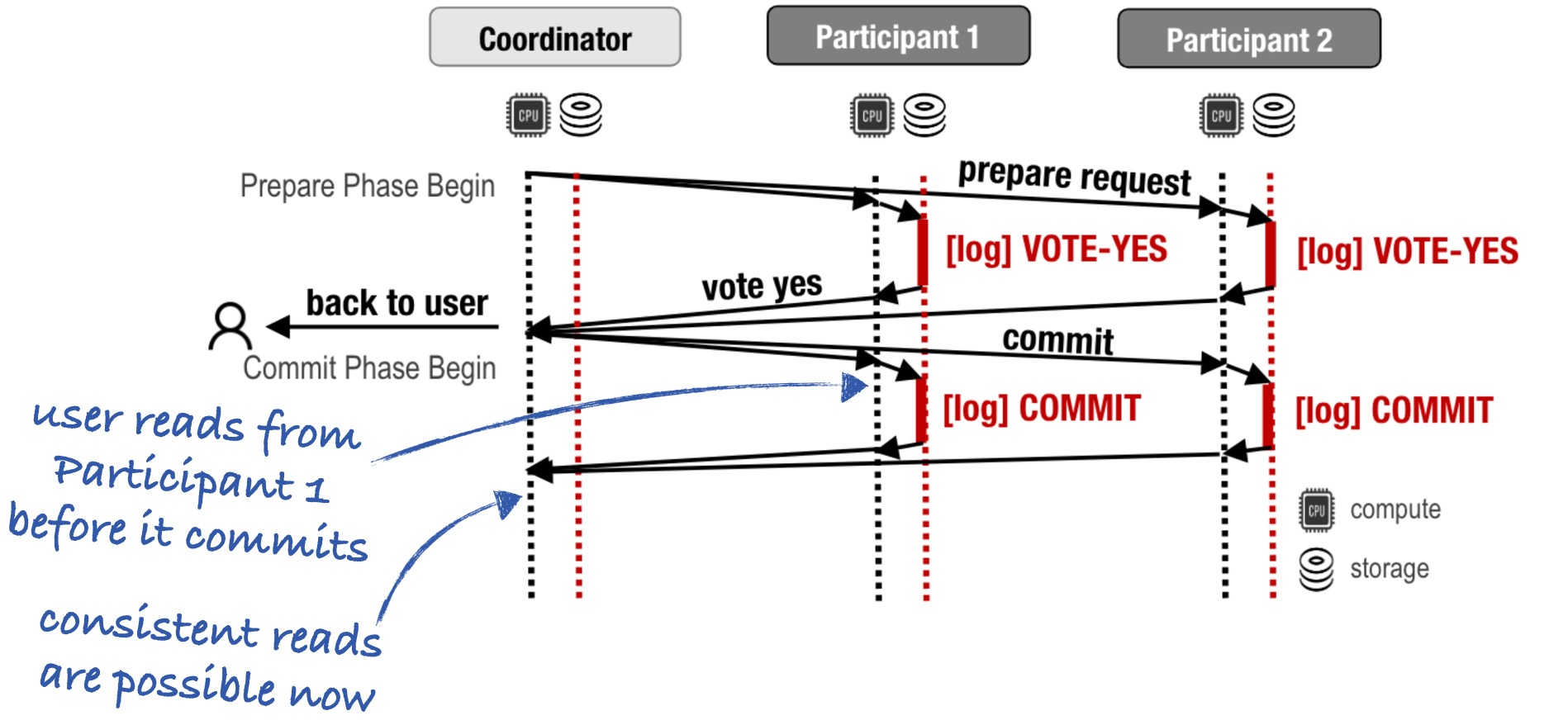

Thought Two: Consistency #

What about reading your writes?

Look at this situation again. As soon as the Cornus coordinator hears all the “yes” votes it replies to the user. What does the user do next? If they read from a participant before it commits, they won’t see their own writes.

If the user never reads, then it’s nice that they’re unblocked as soon as the transaction is durable. If they mix reads and writes, then maybe the coordinator should wait until consistent reads are possible before it replies. It’s still useful to remove the coordinator log delay, but now that only saves one third of the commit latency, not one half.

Thought Three: The Optimization Doesn’t Need Cloud Storage #

If you still want the coordinator log delay optimization, I don’t think it depends on cloud storage. You could rely on the participants to be always available (and replicate them appropriately), and use their logs as the source of truth, like Cornus does.

Thought Four: Cloud Storage Isn’t Magic #

My final caveat is, don’t assume cloud storage is magically invulnerable. You might want to configure a higher replication factor than the authors did. There can be disasters, even in the cloud.