Review: Distributed Reset

Distributed Reset, by Anish Arora and Mohamed Gouda, in IEEE Transactions on Computers, 1994.

Say you have a distributed system, and each node wants the ability to reset all the nodes to some predefined state. “Distributed Reset” is a bolt-on protocol you can add to your system. The protocol involves constructing a spanning tree and diffusing the reset message in three waves through the tree.

Table Of Contents

Spanning tree #

Arora and Gouda’s goal is to augment any distributed system with a distributed-reset module, which requires no additional processes or channels, it’s just some extra code. Distributed Reset brings all nodes to the same “distinguished state”. The authors don’t want to stop the world while the reset occurs: instead, it’s good enough if all nodes pass through the distinguished state, such that the system’s subsequent states are as if all nodes had been reset simultaneously.

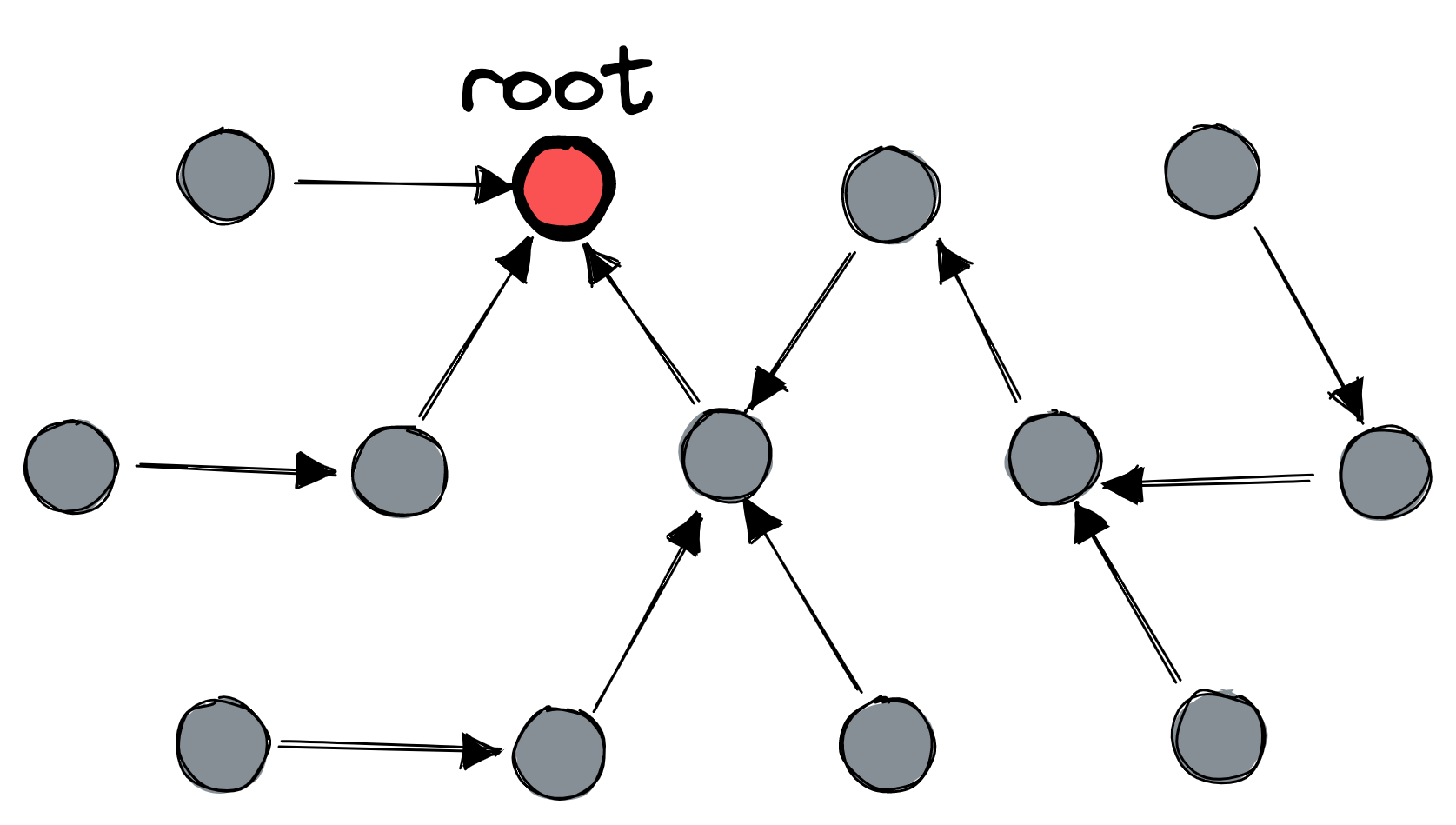

In order to reset all nodes, a message must be able to diffuse from any single node to all the others. To achieve this, nodes continually maintain a spanning tree, a DAG that covers all nodes and has a single root node.

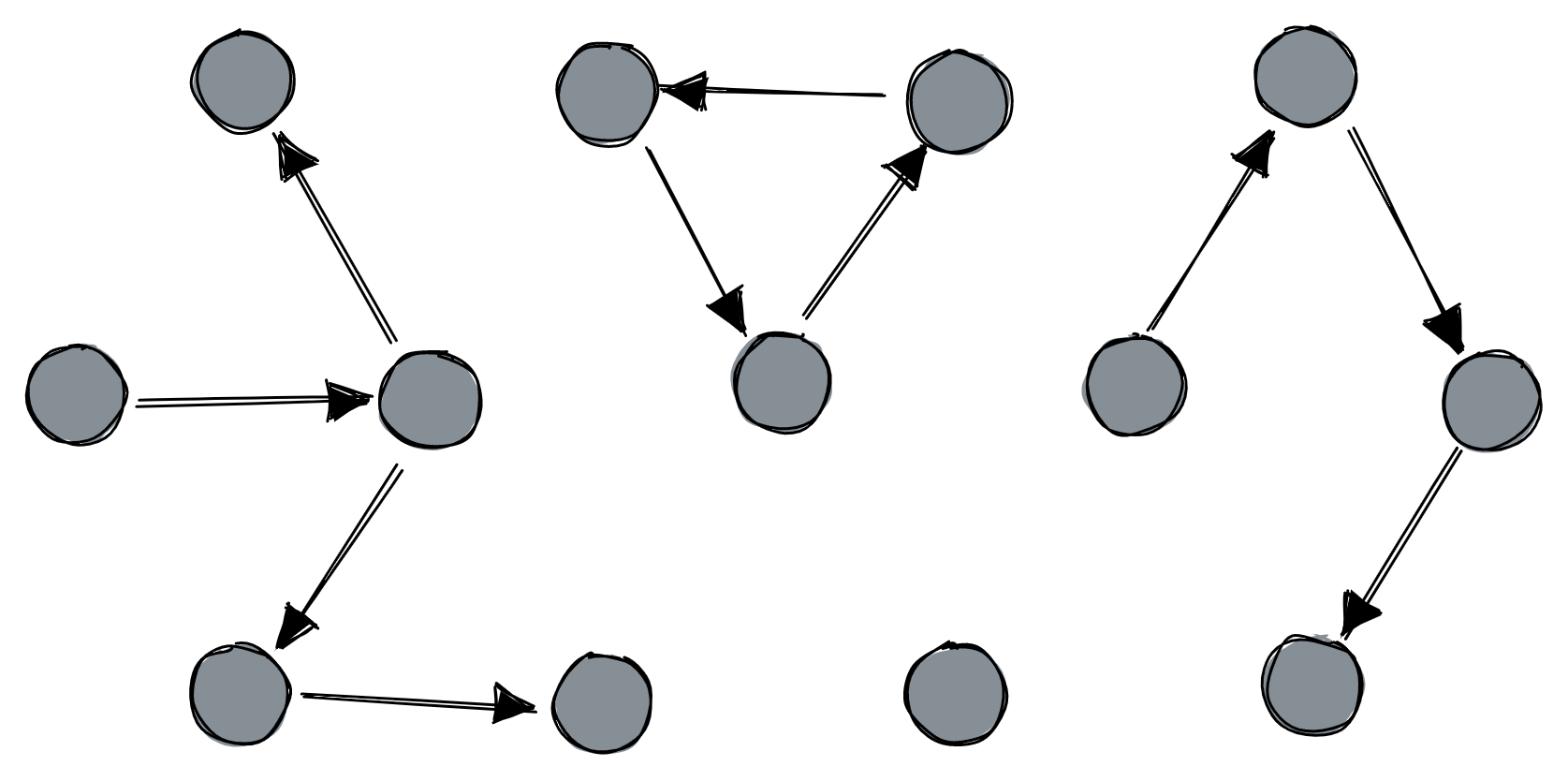

The initial state could be any directed graph, even one with cycles or isolates:

Each node keeps track of which adjacent nodes are alive and figures out who its parent should be, giving precedence to nodes with higher id numbers. How nodes know which peers are alive is an exercise for the reader. The authors assume there’s no network partition (big assumption!) and prove that their protocol is self-stabilizing: from any initial state, or after any topology change, the nodes will eventually re-establish a spanning tree with a single root node.

Diffusing computation #

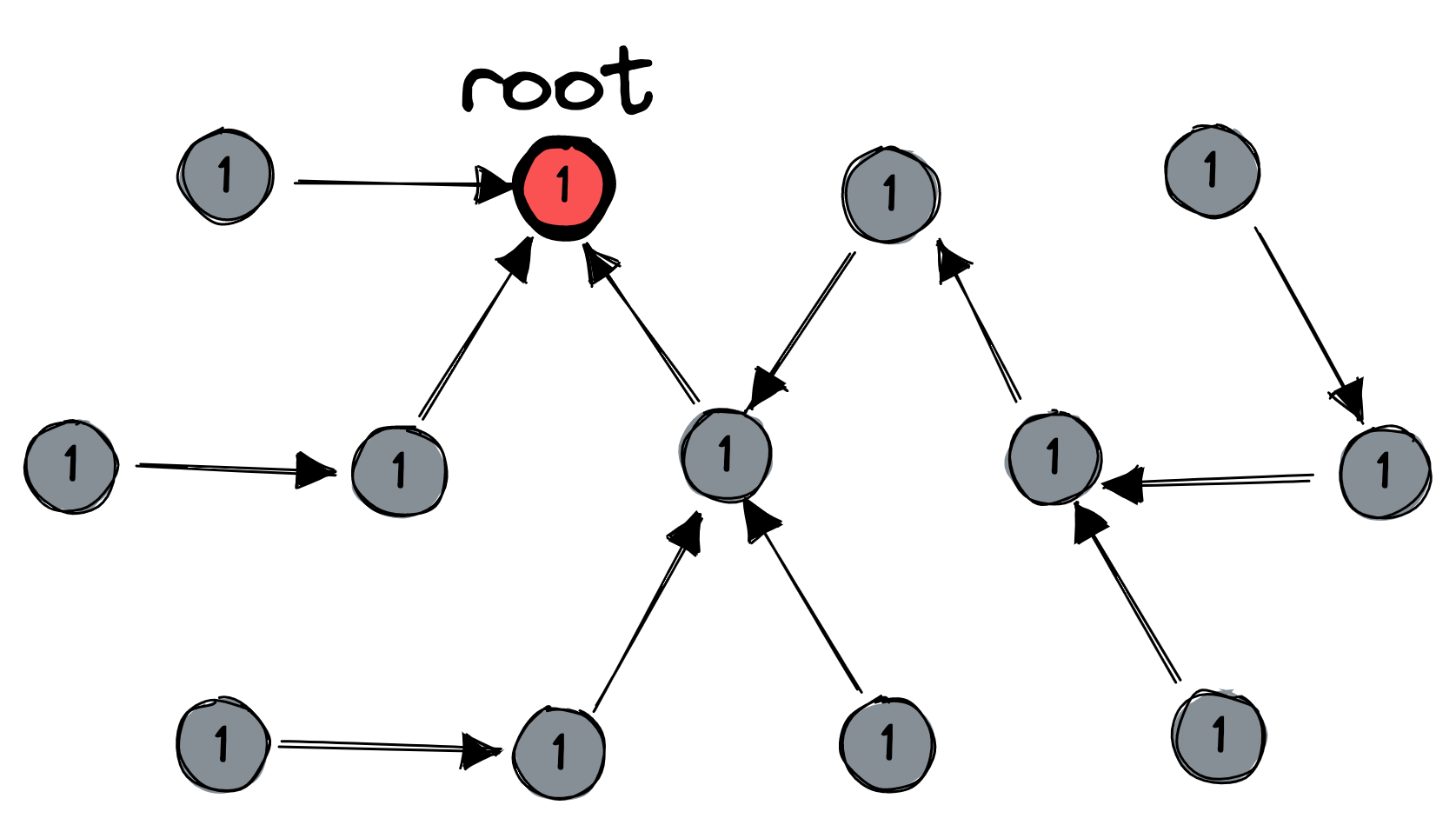

All nodes have a session number, and they somehow all start with the same session number. I’ve shown the initial session number as “1” here:

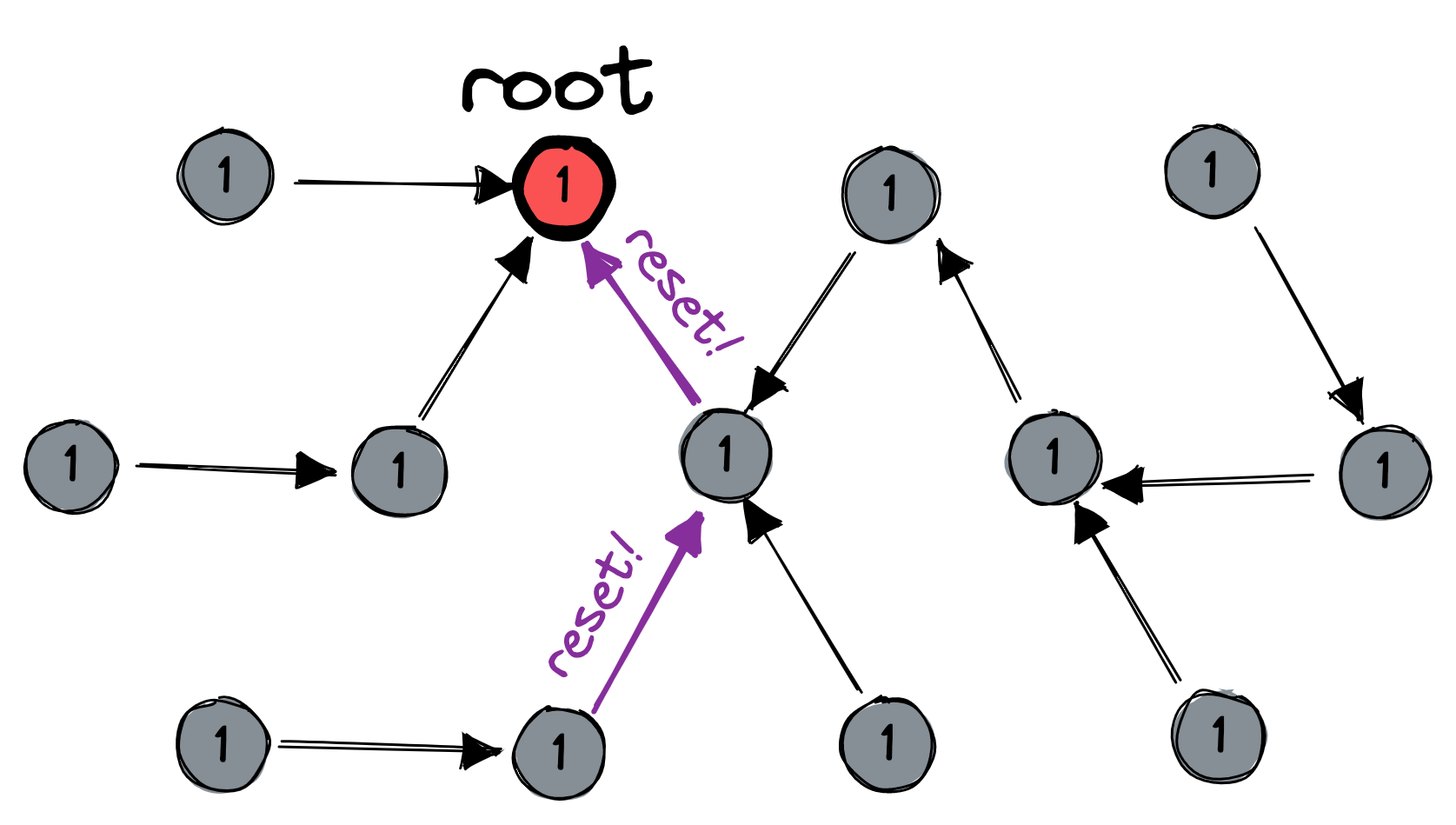

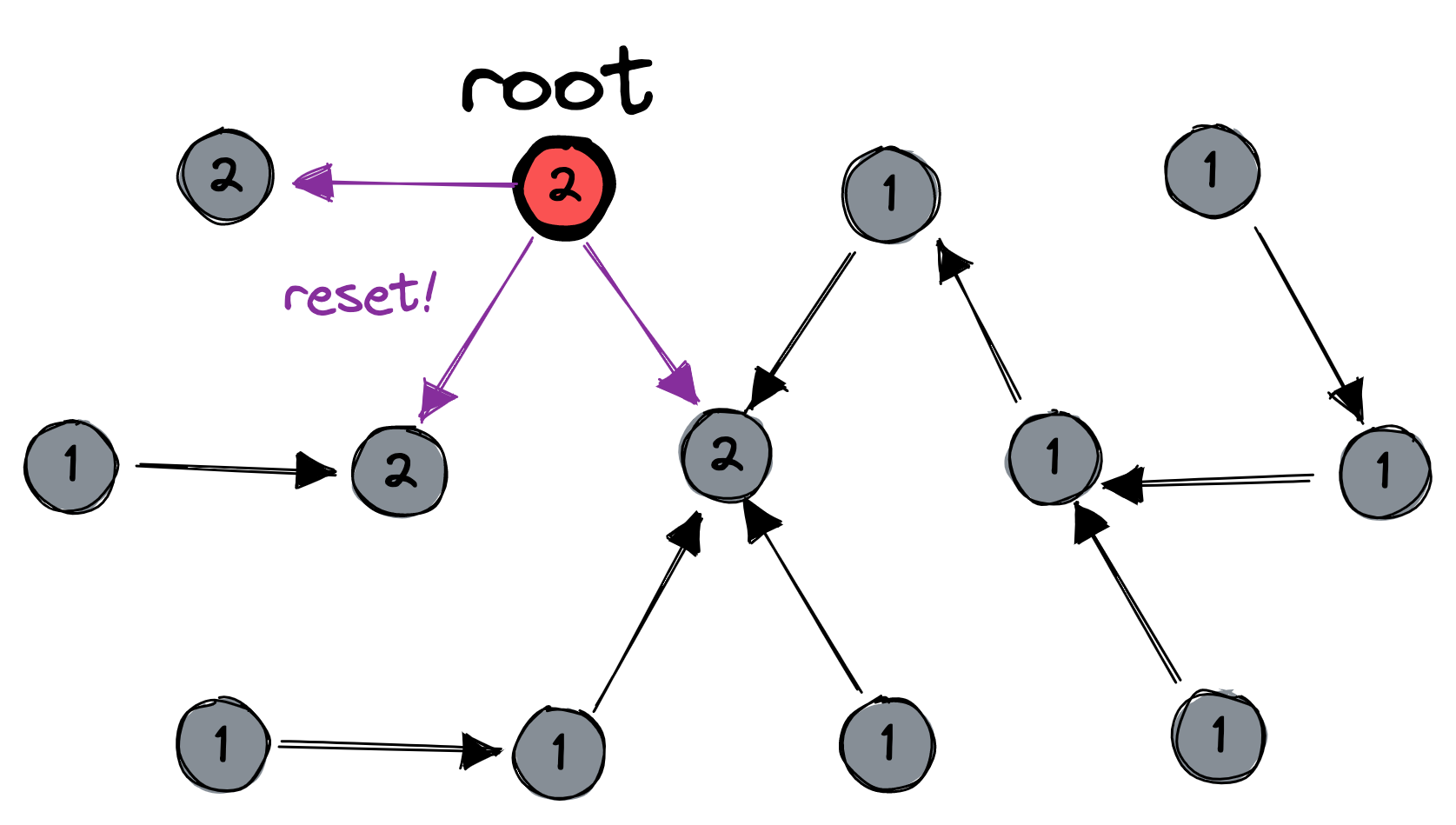

At any time, some node could decide to start a reset. This decision sets off three waves of messages. First, the reset-initiating node sends a message to its parent. The message keeps bubbling upward to the root:

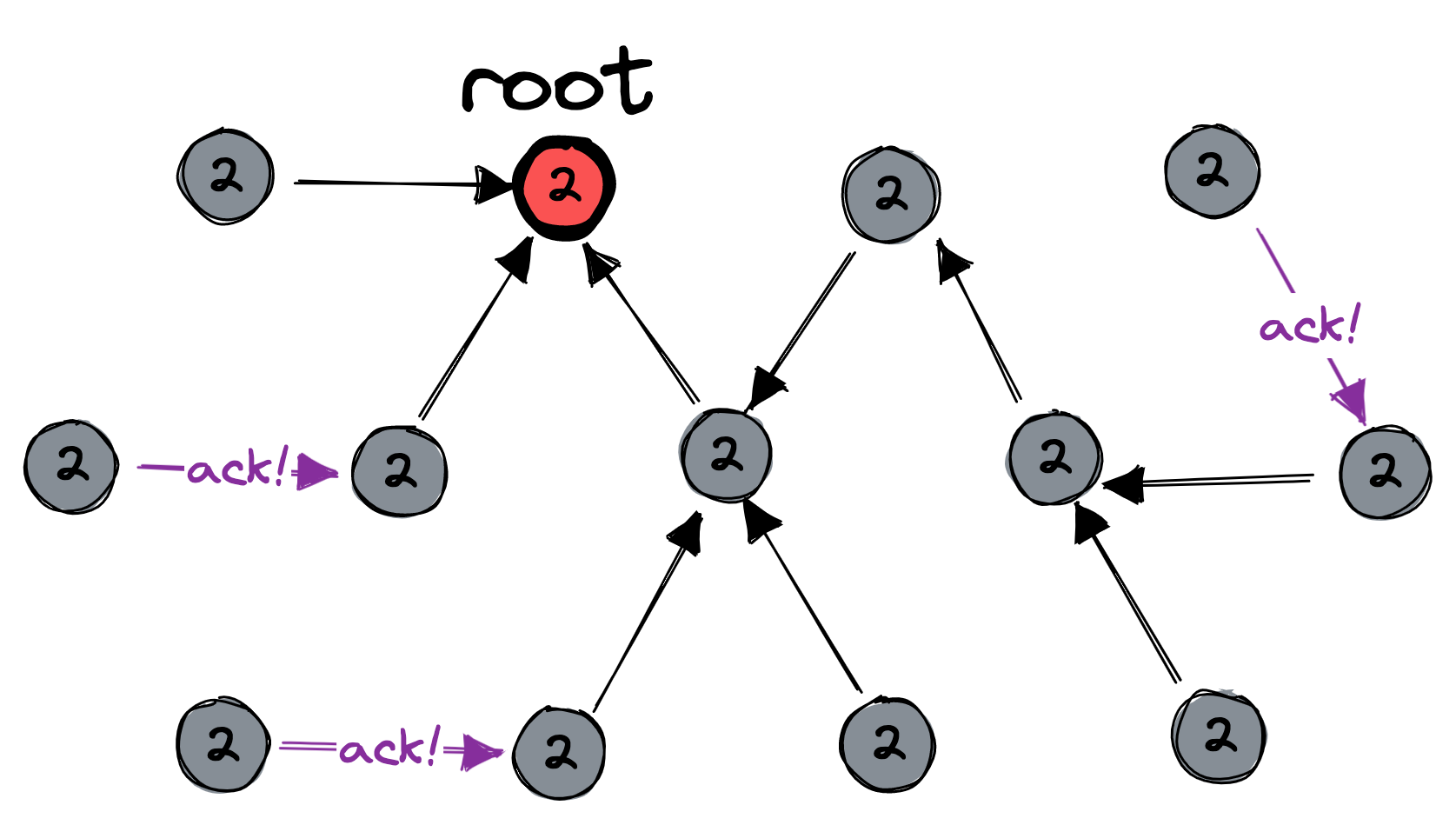

Second, the root resets itself to the distinguished state, and increments its session number. It propagates the message down to its children, who also reset themselves and increment their session numbers, and so on to the leaves:

Third, the leaves send acknowledgements which bubble upward until they reach the root:

Multiple resets could be in progress at the same time; the purpose of the session numbers is to distinguish them. During normal application logic (that is, aside from the distributed-reset protocol), nodes can only talk with other nodes that have the same session number. Thus if Node A has been reset and Node B hasn’t yet, then Node A has session number 2 and Node B has session number 1, and they can’t talk until Node B also resets itself. This guarantees that application logic proceeds as if all nodes were reset simultaneously.

Interestingly, it’s ok for the session number to wrap around when it exceeds some maximum. You could use an 8-byte int, and let the number increment from 255 to 0. The paper says only that the sequence of session numbers must have at least two elements. (From which I infer that the protocol permits only two resets to be in progress.)

That’s the gist of the Distributed Reset protocol. Much of the paper is consumed by meticulous proofs; they’re admirable and I ignored them.

My evaluation #

The paper’s spanning-tree algorithm is simple and robust. I don’t know what advances have been made in the subsequent 30 years for solving the spanning-tree problem, but this seems like a worthy contribution. I wonder if the rest of the paper is obsolete, though.

When is Distributed Reset necessary? Arora and Gouda write,

There are many occasions in which it is desirable for some processes in a distributed system to initiate resets; for example,

- Reconfiguration: When the system is reconfigured, for instance, by adding processes or channels to it, some process in the system can be signaled to initiate a reset of the system to an appropriate “initial state”.

- Mode Change: The system can be designed to execute in different modes or phases. If this is the case, then changing the current mode of execution can be achieved by resetting the system to an appropriate global state of the next mode.

- Coordination Loss: When a process observes unexpected behavior from other processes, it recognizes that the coordination between the processes in the system has been lost. In such a situation, coordination can be regained by a reset.

- Periodic Maintenance: The system can be designed such that a designated process periodically initiates a reset as a precaution, in case the current global state of the system has deviated from the global system invariant.

This seems vague and unconvincing to me. Consider points 3 and 4: I can’t picture what the authors mean by “coordination loss” or “periodic maintenance”. It sounds like they propose Distributed Reset as a Band-Aid over buggy software. Perhaps that’s a useful application.

Now consider points 1 and 2: “reconfiguration” and “mode change” require all nodes to agree to the new configuration or mode … in other words, consensus. And if you’ve solved consensus, you already solved Distributed Reset. You can just use your consensus protocol to make all nodes agree to the “distinguished state”. Furthermore, consensus protocols handle network partitions in predictable ways, whereas the Distributed Reset protocol was designed with the assumption there isn’t a partition; I’m not sure what would happen if there was.

The Distributed Reset paper was published in 1994, before Paxos was published in 1998. But Viewstamped Replication had solved consensus in 1988. What does Distributed Reset offer that isn’t a subset of Viewstamped Replication? It’s possible that Arora and Gouda weren’t aware of VR, or didn’t understand its power. They wouldn’t be the only researchers to do so. It seems that consensus wasn’t a well-distinguished concept among researchers of that era, and it had to be rediscovered a few times before achieving fame. Or perhaps Distributed Reset can succeed in some situations where no consensus protocol can make progress? This is past the frontiers of my knowledge, if you know then please tell me.

Update: Why not use consensus? #

Murat Demirbas educated me about the context of this paper. Anish Arora was Murat’s academic advisor a few years after this paper was published. In that era, Gouda, Arora, and Demirbas all studied self-stabilization, a branch of distributed systems that I’m not familiar with. The field was inaugurated by a 1974 Edsger Dijkstra paper. A self-stabilizing system can start from any state and reach a good state (which upholds some desirable invariants) in a predictable number of steps, unless it’s perturbed again by some change or failure. We can see that style of reasoning in this paper’s spanning tree algorithm: it doesn’t begin with some initial state, rather it starts from any state and is guaranteed to construct a tree in a bounded number of steps. Murat says this paper solved a problem that had been open for some years before it was published.

My own specialty is distributed databases, so given a problem like “Distributed Reset”, I reach for a consensus protocol like Raft. But Raft and this paper are intended for very different scenarios. Raft assumes a small number of nodes, which are initiated with a known state, and have stable local storage. Distributed Reset works for a large and ever-changing set of nodes with no storage. Raft assumes all nodes can talk with each other directly, but Distributed Reset can handle a partly-connected network graph. The Distributed Reset protocol is more “local” than Raft, requiring each node to execute only simple rules based on its local knowledge, eventually leading to correct system-wide behavior.

Raft requires a majority of nodes to stay up: you can’t reconfigure yourself to a smaller set of nodes if the old majority can’t acknowledge the reconfig! Distributed Reset, however, maintains availability despite the loss of practically any number of nodes. In CAP terms, Distributed Reset prefers availability, but offers no consistency: you don’t know when or if the reset completes, but you can always start another reset.

Thanks to Murat for explaining this to me. Search for “stabilizing” on his blog for more, particularly his articles on cloud fault tolerance and his proposal for extremely resilient systems.

Photos © A. Jesse Jiryu Davis.