Review: Amazon MemoryDB: A Fast and Durable Memory-First Cloud Database

Amazon MemoryDB: A Fast and Durable Memory-First Cloud Database, by six AWS engineers, in SIGMOD 2024. AWS hacked up Redis (I mean this respectfully) to produce a Redis-compatible database-as-a-service called MemoryDB, with better durability and consistency. Here’s a video of my presentation to the DistSys Reading Group, and a written review of the paper below.

The Problem #

It’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me.

Redis is popular because it’s fast and supports fairly powerful data structures, which makes some kinds of applications much easier to build. But Redis has basically no durability or consistency guarantees. So Amazon wants to sell a better Redis.

Digression: there’s been some license drama. Redis’s owner, Redis Labs, changed the license from open source to source-available. My company made a similar move and I think it’s justified. There’s a fork of open source Redis called Valkey now, and it has a new logo:

I have this thing where I get older but just never wiser.

Valkey sounds like a Norse warrior woman to me. I think their logo should look like this:

I’m a monster on the hill.

However, AWS marketing says MemoryDB is “OSS Redis-compatible”, and they don’t mention Valkey, I don’t know how this will play out long term. Will Amazon contribute to Valkey? Or will proprietary Redis, Valkey, and AWS’s version of Redis drift apart forever?

One day I’ll watch as you’re leaving.

Anyway. Amazon wants to sell a better Redis, with stronger durability and consistency. How are they going to do it?

The Solution #

Guaranteeing durability and consistency in a distributed database is always complex. In this paper, the authors’ solution is to make a black box, call it “the transaction log”, put all the complexity inside, and close the box.

I should not be left to my own devices.

The authors don’t describe the transaction log internals; we don’t know how it provides the guarantees on which MemoryDB relies. Presumably that’ll be a future paper, or maybe we can just infer it’s running Raft or Paxos. This is frustrating for me because I’m here for the distributed systems, but this isn’t a distributed systems paper—it’s mostly a software engineering paper. This paper is about how Amazon decomposed Redis into two parts: 1) the transaction log, and 2) everything else. They replaced the log with something better, put the parts back together, and created MemoryDB.

Too big to hang out, slowly lurching toward your favorite city.

MemoryDB Architecture #

Figure 1 from the paper.

Here’s the MemoryDB architecture. Clients send writes to the primary. In vanilla Redis, the primary streams operations asynchronously to secondaries (aka “replicas”). The MemoryDB primary saves writes to the transaction log synchronously. How did the authors make the change from async to sync without rewriting Redis internals? There’s a doohickey called a Tracker which knows when writes become durable, delays acks until then, and blocks reads on dirty data. This provides linearizability on the primary. My impression is it lives outside the Redis core code, and it intercepts requests and replies.

Secondaries receive entries from the transaction log only after they are multi-AZ-durable. A client can opt in to read from one replica and get sequential consistency, or multiple replicas and get eventual consistency. In both cases, MemoryDB secondaries have better consistency than Redis secondaries, since the former don’t observe writes that can be rolled back.

Off-Box Snapshotting #

Figure 2 from the paper.

Snapshots are useful for initializing new followers or disaster recovery. Normal Redis does snapshotting by forking the main process. One child keeps processing transactions (taking advantage of copy-on-write) while the other child creates the snapshot from its read-only copy of the data. These two children are competing for RAM and CPU, though, so the machine has to be overprovisioned to make headroom for occasional snapshotting.

With MemoryDB, when Amazon wants to take a snapshot it does it “off-box”. They start up a new Redis machine, restore it from the last snapshot in S3, replay the subsequent transactions, save a new snapshot to S3, and terminate the Redis machine. The customer workload proceeds without interference.

Advantages of a Disaggregated Log #

MemoryDB is much like Aurora: it keeps the open source execution layer at the top, ensuring compatibility and avoiding reimplementation, but replaces the transaction log at the bottom with a proprietary service that’s more scalable and durable. The authors claim their mysterious transaction log service guarantees 11 9s of durability. That’s more 9s than you can shake a stick at!

Tale old as time.

Once the log is separated from the execution layer, you can scale durability separately from availability. For example, a single-primary-only deployment is low-availability but high-durability. If the primary dies, you may wait a while for a new primary to be initialized from the last snapshot, but you won’t lose data.

Some other advantages seem Redis-specific. Since Redis is single-threaded, it’s crucial to offload as much work from the primary as possible. A vanilla Redis primary must work to fan-out log entries to its secondaries, but a MemoryDB primary writes each entry only to the transaction log, which handles fan-out. Furthermore, Redis elections provide few guarantees: a newly elected primary might be missing recent writes, and there can be multiple primaries. MemoryDB uses the log’s strong consistency as part of its election protocol to guarantee a single primary with all the previous primary’s writes.

Scaling #

MemoryDB, like Redis, is both sharded and replicated. Amazon can scale MemoryDB nodes up or down, in or out, in three dimensions:

- The number of replicas per shard.

- Vertical scaling (using more or less powerful instances).

- Horizontal scaling (adding or removing shards).

Number of replicas: More replicas permit read scaling (with weak consistency) and higher availability (there are more hot standbys). To add a replica, AWS restores one from the last S3 snapshot, then replays the transaction log.

Vertical scaling: AWS replaces each secondary with a new one using a different instance size, then hands over leadership and deletes the old primary. The paper says MemoryDB has “a collaborative leadership transfer, where the old instance actively hands over leadership, which minimizes downtime”. There are no details, but MongoDB and some other systems have similar ideas. I can imagine that the old primary ensures the new one is nearly caught-up in the transaction log before it starts the handover, then it stops accepting writes, relinquishes its lease, and tells the new primary to run for election immediately instead of waiting for a timeout.

Horizontal scaling: Redis supports sharding using something like consistent hashing. There are 16,384 slots. Each slot has a subset of the keys, assigned according to a hash of the key. Each shard is a replica set, and each shard owns a subset of the slots. Perhaps open source Redis can change the number of shards and reassign slots, the paper doesn’t cover this. In MemoryDB, slots are reassigned in the way you’d expect: the old owner streams data and data-changes to the new owner until they’re almost in sync, then the old owner stops accepting writes, streams the final updates to the new owner, and they both commit a change to the sharding metadata to transfer ownership.

Presumably the transaction log service can also scale, but the log service is a black box so we don’t know.

Upgrading Versions #

This part of the paper was clever and novel to me. MemoryDB upgrades the software version of a replica set thus:

- For any v1, v2: v2 can read v1’s log entries, but maybe not vice-versa.

- Each log entry is marked with the version of the primary that created it.

- Secondaries upgrade to v2 first.

- If there’s a failover during upgrade and a v2 node becomes a primary, v1 nodes don’t replicate its entries.

- Snapshots are built with v1 until all nodes are v2, so snapshots are legible if the upgrade is aborted.

This is simpler than MongoDB’s solution. It also doesn’t solve all the problems MongoDB solves, but still—I admire it.

Their Evaluation #

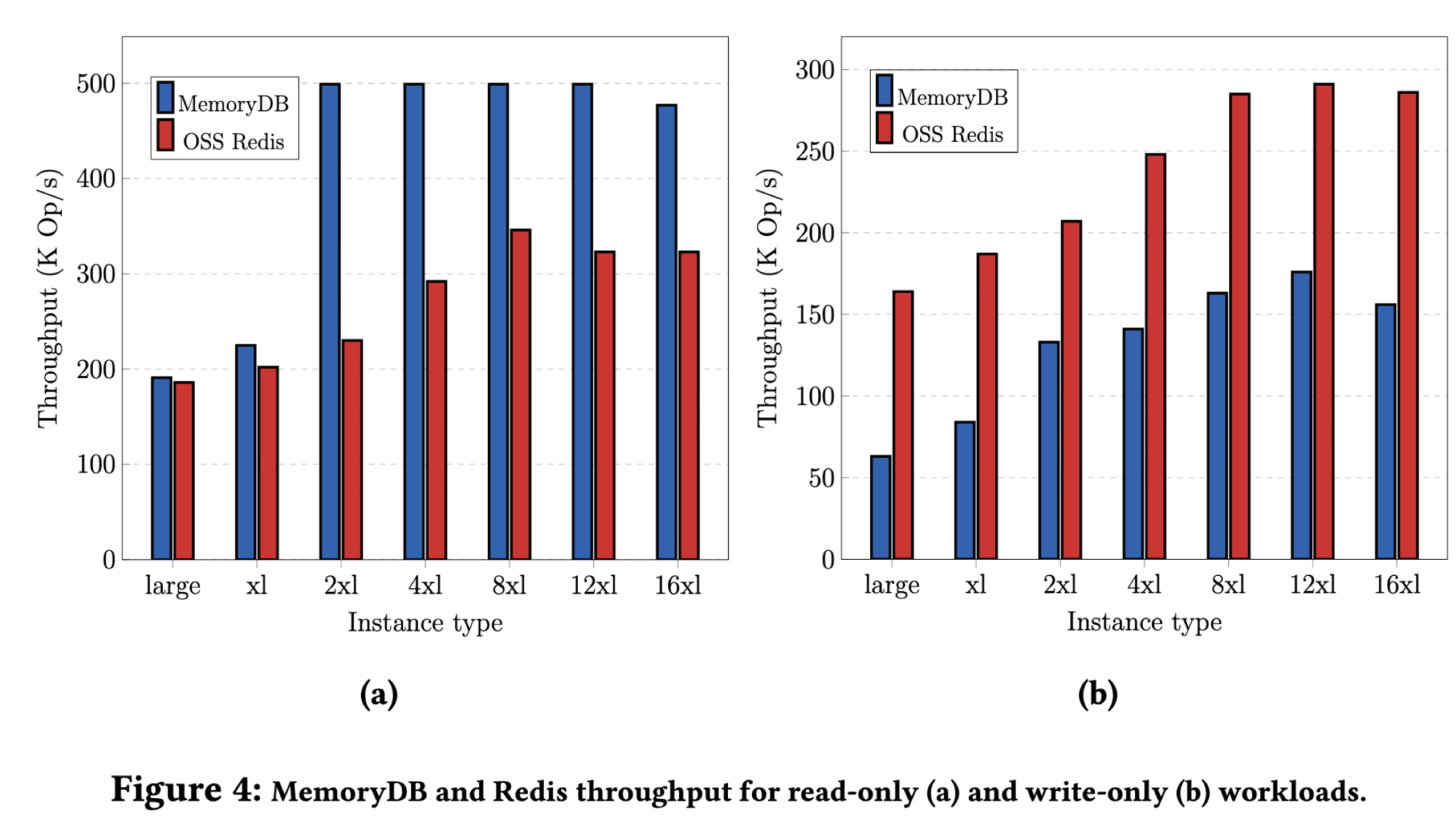

For a read-only workload, MemoryDB is about as fast as Redis on small instances. There’s a step change when the instance size is upgraded to 2xl, then no more benefit. The authors say this is because of “Enhanced IO Multiplexing”. I think this is because Redis is single-threaded, but Enhanced IO Multiplexing lets some IO work be offloaded to other threads. Apparently that removes a bottleneck when they upgrade to 2xl, but then they hit some other bottleneck and bigger instances don’t help.

For a write-only workload Redis writes faster than MemoryDB, but there’s no durability guarantee. It’s interesting that, even though Redis is single-threaded, it can still get a performance boost from a bigger instance. Bigger instances have the same CPUs, just more of them, which I think is useless for Redis. But bigger instances also have more network bandwidth, maybe that helps.

My Evaluation #

This is a solid industrial-track paper about pragmatic software engineering for a distributed DB. It’s frustrating for distributed algorithms buffs, but we’re not its audience. For us, I wish Amazon had published a paper about the log first, or included some log details in this paper. Nevertheless I like it. The upgrade protocol is wisely designed.