Review: PolarDB-SCC: A Cloud-Native Database Ensuring Low Latency for Strongly Consistent Reads

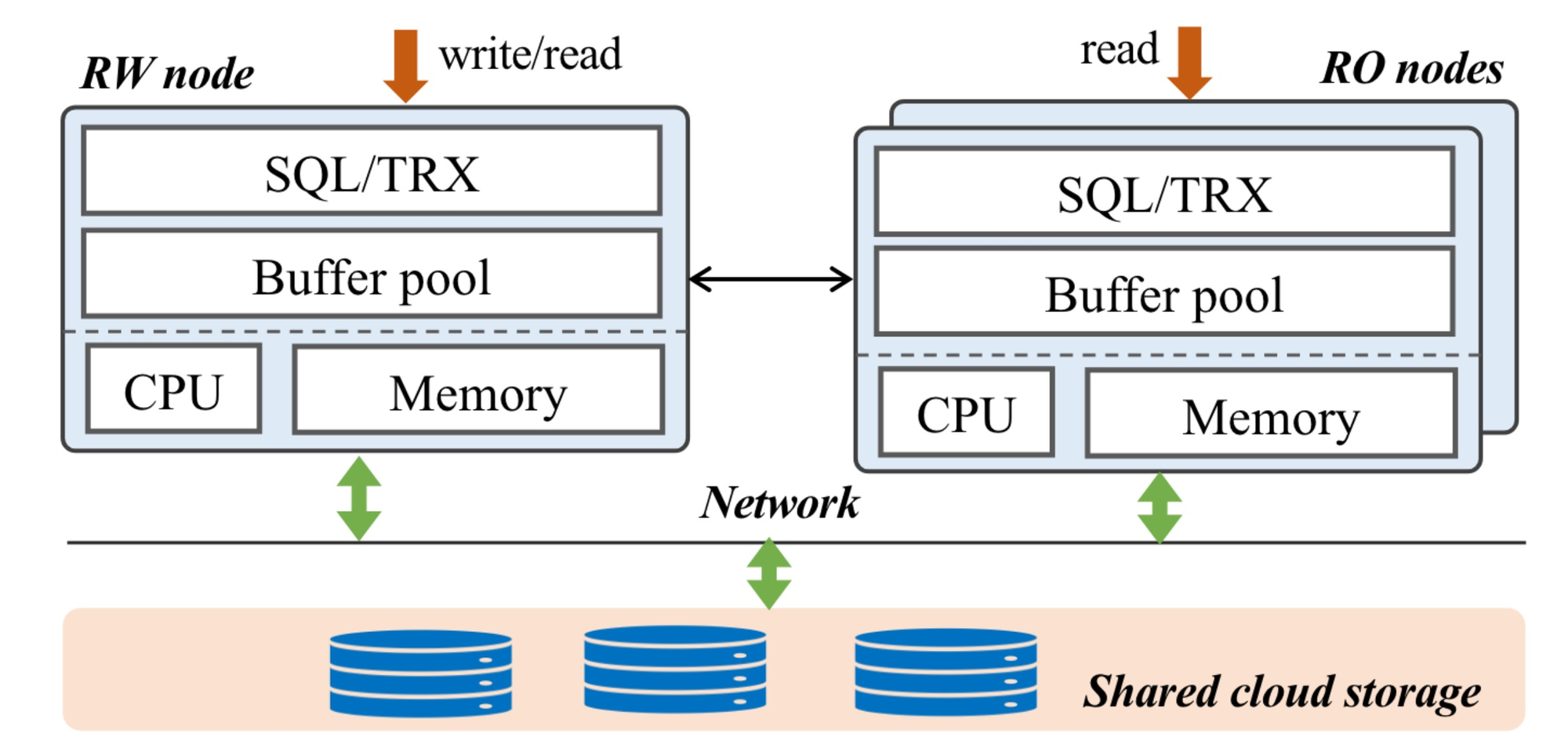

PolarDB is Alibaba’s cloud-native SQL database. It has the now-typical architecture of one read-write (RW) node and several read-only (RO) nodes as hot backups, sharing a disaggregated storage layer.

Figure 1 from the paper.

Figure 1 from the paper.

Each RO has an in-memory cache; to keep this updated, the RO streams the write-ahead log (WAL) from the RW and replays it on the RO’s locally cached data. Nevertheless the RO’s cache is usually a bit out of date, so RO queries may return stale (inconsistent) data. Alibaba either has to accept this inconsistency, or run all queries on the RW. Very fast replication will increase the chance of a consistent RO read, but doesn’t guarantee it. Therefore, Alibaba applications that require consistency only query the RW, bottlenecking on the RW’s CPU and leaving the ROs nearly idle.

In “PolarDB-SCC: A Cloud-Native Database Ensuring Low Latency for Strongly Consistent Reads”, some Alibaba engineers introduce algorithms for accelerating replication and guaranteeing consistent reads from ROs. (SCC stands for “strongly consistent cluster”.) Now that all applications can safely read from ROs, Alibaba can usefully autoscale the number of ROs and load-balance queries among all the nodes behind one serverless endpoint.

Fast replication #

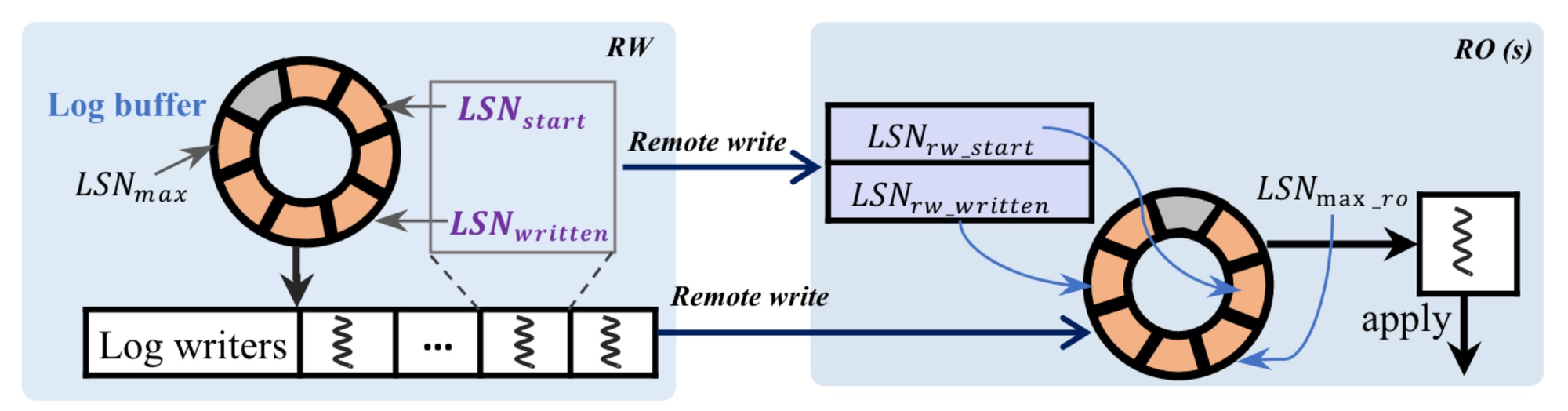

ROs use one-sided RDMA to read the WAL from the RW. The WAL is a ring buffer in the RW’s memory. The nodes coordinate to ensure that RWs can safely read it, and the RW won’t overwrite entries before they’re replicated. The paper describes the protocol in detail; it looks like lock-free ring buffers I’ve seen before, but I’m no expert.

Figure 7 from the paper.

Figure 7 from the paper.

Shipping logs with RDMA spares the RW’s CPU, and the authors claim it also minimizes network overhead. (I’d like to know more, see my evaluation below.)

Read-wait #

When a client queries an RO, the RO checks the RW’s global last-write timestamp. If the RO has replayed the WAL up to that timestamp, then the RO’s local data is fresh enough to run the client’s query. Otherwise, it waits until it has replayed up to that timestamp before running the query. The RO fetches the timestamp from the RW with one-sided RDMA, to spare the RW’s CPU and perhaps to minimize latency. Again, I’d like to see an experiment that compares this with non-RDMA fetching.

The authors describe an optimization they call a Linear Lamport timestamp, to avoid hammering the RW with a timestamp fetch for each RO query. If one RO query r2 begins fetching the RW timestamp at time T, and it happens that another RO query r1 began before T but hasn’t started fetching the timestamp yet, then r1 can wait for the fetch to complete and reuse that timestamp.

My adaptation from the paper’s Figure 5.

This sounds like an important optimization, but I wonder how often it happens. The authors don’t tell us the ratio of queries to fetches. Reusing a fetch seems to require task reordering on the RO: r1 starts before r2, but r2 begins fetching the timestamp first. Could this result from jittery thread scheduling, or because some queries need more preprocessing than others? Perhaps Nagle’s algorithm would let more queries reuse each fetch?

Hierarchical modification tracker #

Even if the RO hasn’t caught up to the RW’s global timestamp, almost all its cached data is fresh, so it can run queries on that fresh subset. The modification tracking table (MTT) lets the RO cheaply determine what data is in the fresh subset.

The RW maintains last-written timestamps at three levels: global, table, page. (A page is a chunk of memory, there are many pages in a table.) The RW’s MTT has two hashtables: one maps tables to timestamps, the other maps pages to timestamps. When the RW commits a transaction it updates the global timestamp and the timestamp for each affected page and table in the MTT.

![]() Figure 6 from the paper.

Figure 6 from the paper.

When the RO starts a query, it first fetches the RW’s global timestamp and checks if it has applied the WAL up to that timestamp; if so the RO is fresh enough to run the query. If not, the RO fetches the relevant table timestamp(s) and checks those. If that check fails, it fetches the relevant page timestamp(s). If that check fails, it’s run out of options and it has to wait. By checking timestamps at these three levels (with the Linear Lamport timestamp optimization, when possible) the RO has the opportunity to run queries on fresh subsets of its data, without waiting to be globally caught up.

The table/page hashtables in the RW’s MTT are fixed-size memory regions of a few hundred megabytes; an RO learns these regions’ addresses when it first connects to the RW, so it can read them over RDMA. Hash collisions are common. If several tables (or pages) have the same hash key, the RW uses the latest timestamp as the value for that hash key. This is pessimistic: it records the latest time that any of the colliding tables (pages) could’ve been modified. Thus when the RO checks that it has caught up to all the relevant timestamps, it may wait unnecessarily, but it won’t violate consistency.

When the RO fetches table/page timestamps, it updates its local copy of the MTT. This means the RW and RO MTTs don’t converge; the RO’s copy has recent timestamps for the data it’s queried, but it doesn’t update timestamps for other tables and pages. Furthermore, the timestamps the RO fetches can be wrong: too recent, due to hash collisions on the RW. It’d be interesting to study how the interaction of access patterns and hash table design affects the MTT’s accuracy on ROs, and causes unnecessary waits.

Their evaluation #

The evaluation is extensive. The authors test PolarDB deployed with one RW and one or more ROs. They run the standard benchmarks Sysbench, TPC-C, and TATP, plus an Alibaba workload. They compare PolarDB-SCC to three configurations:

- Default: The RW handles all queries.

- Read-wait: The ROs use “the vanilla read-wait scheme”, which is vaguely explained. I think the ROs check the RW’s global timestamp (over RDMA?), but there is no MTT or Linear Lamport optimization.

- Stale-read: The ROs run queries immediately, with no consistency guarantee.

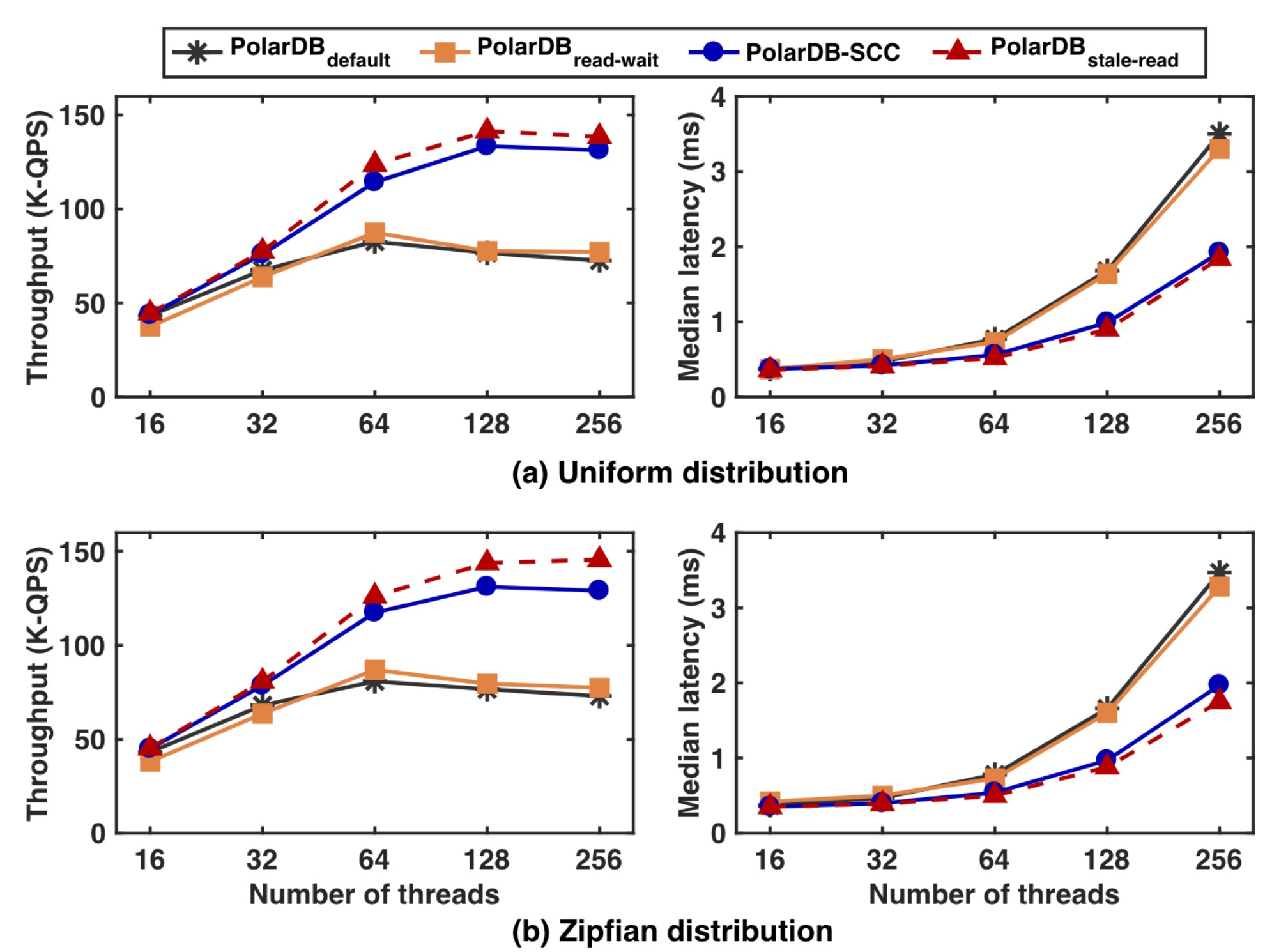

PolarDB-SCC is nearly as fast as stale-read, except of course it doesn’t serve stale reads.

The Sysbench test is fun. They try two workloads: one accesses all data with uniform likelihood, the other is a skewed workload that accesses some hot data much more than others. When all data is accessed uniformly, the RO usually has a fresh enough copy of the data being queried, so the timestamp-fetch (to update the RO’s MTT) is the only overhead compared to stale-read. The performance indicates that timestamp-fetch is very fast. With a skewed access pattern, hot data is more likely to be written on the RW and immediately queried on the RO, so the RO often has to wait to catch up, and throughput is a tiny bit lower:

In all cases, PolarDB-SCC beats the default, because it doesn’t bottleneck on the RW’s CPU, and beats read-wait, which often waits unnecessarily.

The authors compare PolarDB-SCC’s performance to MySQL Group Replication and to two anonymous databases “from two top cloud providers”, which they say they can’t name due to the DeWitt clause. This surprised me, since so many database vendors permit benchmarking nowadays; it might have been more valuable to readers if the authors had compared PolarDB-SCC to competitors they can name. Maybe Alibaba wanted these comparisons for their own use, so the authors decided they might as well publish them.

My favorite part of the evaluation is when the authors measure the contribution of each feature: the Linear Lamport timestamp and MTT each approximately double throughput compared to “vanilla read-wait”. With those two features enabled, RDMA log shipment increases throughput only a few more percent. I think that’s because the modification tracking table has made it less crucial to replay the log quickly: chances are, the queried data was last modified a while ago and the RO is fresh enough, which it can confirm by checking the MTT.

My evaluation #

There’s a lot of underutilized dark matter in the cloud, and backup nodes are a big portion of it. Any technique that makes them useful for queries is enticing. The Linear Lamport timestamp and MTT seem clever, and I guess they really work—PolarDB-SCC is in production.

Those two features could be implemented by any database, but the RDMA protocols require special hardware, so I wish the authors compared non-RDMA implementations of each feature. How much worse would PolarDB-SCC be if it didn’t use RDMA for fetching the global timestamp or the MTT? And how much slower would log shipment be without RDMA? Despite all their experiments, the authors didn’t isolate RDMA’s advantage for each feature, and those of us without access to RDMA would like to know. My MongoDB colleague Amirsaman Memaripour co-authored two papers that experiment with RDMA for MongoDB replication[1, 2], it looks zippy.

That’s my only complaint. This paper describes an exciting approach that could save a lot of power and carbon for all cloud databases, I hope to try it myself.

RDMA vs RPC? Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Une Voiture de Course Singer, Avenue des Acacias, Paris, 1912.

RDMA vs RPC? Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Une Voiture de Course Singer, Avenue des Acacias, Paris, 1912.