Review: Rethink the Linearizability Constraints of Raft for Distributed Systems

In Rethink the Linearizability Constraints of Raft for Distributed Systems (behind the IEEE paywall, dammit), some academic researchers describe Raft optimizations that make reads and writes quicker, while preserving linearizability. Raft and linearizability are my specialities, and I’m pretty sure I see mistakes in this paper. The ideas are worth considering anyway. I recommend it, if you or a friend has an IEEE subscription.

Table Of Contents

Lower-latency writes #

Classic Raft #

Here’s how writes work in classic Raft, as described by Diego Ongaro in his paper and thesis:

- A client sends a write command to the leader.

- The leader appends a log entry, which includes the command, to its log at position i.

- The leader waits for the entry to be replicated by a majority of followers, i.e. committed.

- The leader advances its commitIndex to i.

- The leader applies the command to its copy of the state machine.

- The leader advances its lastApplied index to i.

- The leader replies to the client with the command’s result.

The commitIndex and lastApplied variables are separate for concurrency’s sake. One thread is responsible for communicating with followers and advancing the commitIndex. Another thread applies committed commands and advances lastApplied. That’s how Ongaro built his reference implementation, LogCabin, and it’s a good idea for any multithreaded Raft.

Commit Return optimization #

In the “Rethink” paper, the authors propose that the leader replies to the client as soon as the entry is committed, without waiting until it’s applied. They call this optimization “Commit Return.” It works for blind writes, where the client doesn’t need to know anything about the command’s result besides “it was committed.” E.g., if the state machine is a key-value store and the client sends a command like set x := 1, the leader could reply “ok” before it updates its state machine.

Commit Return doesn’t work when the client sends a command that returns a data-dependent value, like return ++x. The leader must apply the command before it knows what result to return to the client. (Can the leader know at commit-time what the return value of ++x will be? No, there might be another committed and unapplied command in the pipeline that modifies x before ++x is applied.)

I’m skeptical #

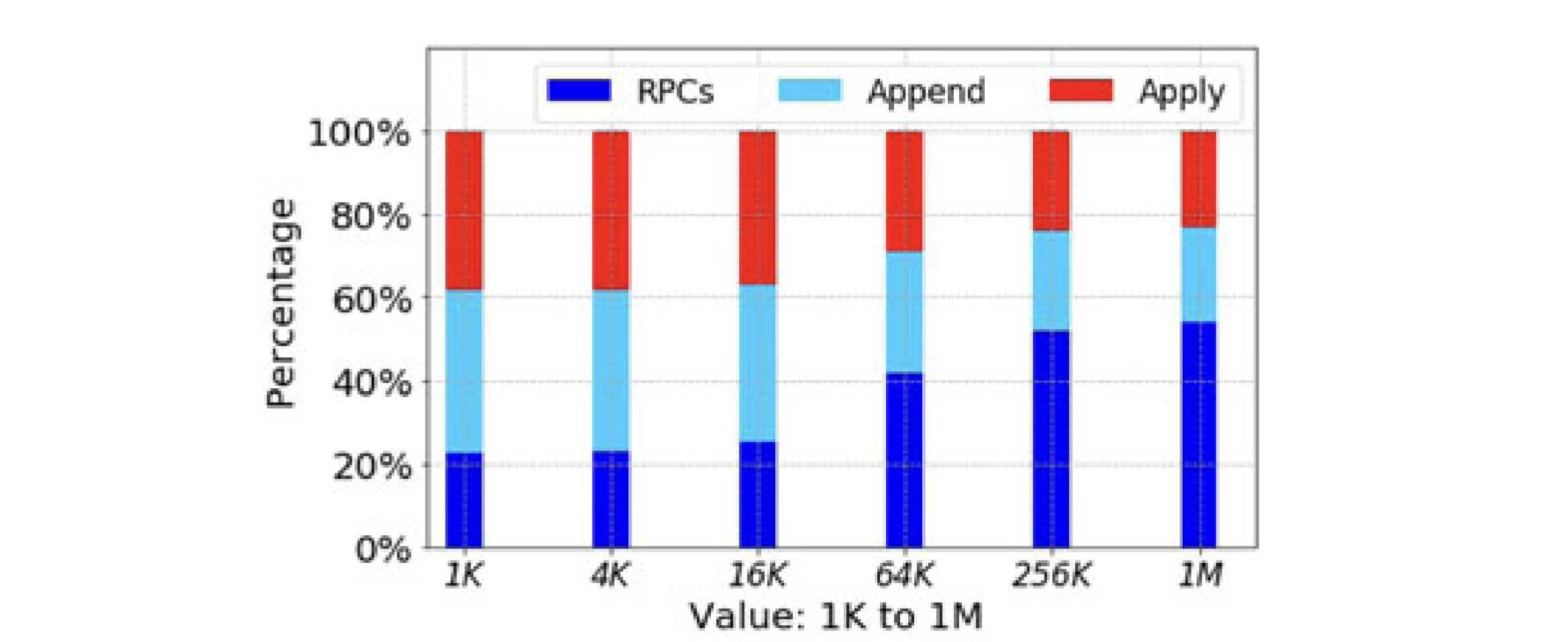

The authors claim that Commit Return is a big win, because sometimes applying a command takes much longer than committing it. This is surprising to me, because like most distributed systems people I assume that network latency dominates, so committing takes most of the time. The authors argue the opposite, and they construct a benchmark where this is true, with five nodes in a single data center connected by a high-speed network. The authors’ Figure 4 shows the percentage of time the leader spends appending entries to its log, or communicating with followers, or applying commands. With 1-kilobyte commands, 40% of write command latency is attributed to applying the command:

Figure 4 in the “Rethink” paper.

I admit that applying commands could be slower than majority-replicating them in this situation. But usually, you deploy a system across multiple availability zones—if you’re going to the trouble of replicating, you might as well be truly fault tolerant. Across AZs, you’re likely to see at least 1 ms of latency. And if you care about latency, then your application is OLTP, and your commands are probably mostly much smaller than 1 kilobyte and very quick to apply.

Oddly, I see that applying takes a larger percentage of the time for smaller commands in their benchmark. I guess there’s a lot of fixed overhead per command when their system applies commands, so small commands replicate quickly and take a comparatively long time to apply. The authors say, “Apply is slow because the apply operation involves writing the state machine log to disk.” But the authors separately measure the time spent appending to the Raft log. I wonder what additional logging is part of applying in their system?

Commit Return is a useful idea, regardless. In a more normal multi-AZ deployment, where most of the latency is the network’s fault, Commit Return reduces latency a smidge for blind writes, from the client’s perspective. The bulk of the paper isn’t about Commit Return, anyway: it’s about read optimizations that are independent of Commit Return. That part of the paper is more interesting, and definitely has a mistake!

Lower-latency reads #

Classic Raft #

Here’s how reads work in Raft:

- A client sends a query to the leader.

- The leader sets the query’s readIndex to the leader’s current commitIndex.

- The leader waits until its lastApplied ≥ the query’s readIndex.

- The leader runs the client’s query and returns the result.

This ensures the client sees the effect of all writes that were committed before the query started.

But that’s not enough to guarantee linearizability! The problem is, a Raft leader is never sure that it’s the real leader, or if it’s been deposed by a newer one. If it’s deposed, then the newer leader is executing writes that the deposed leader doesn’t see, and the deposed leader’s reads will reveal stale data, violating linearizability.

How does a Raft leader ensure it isn’t deposed? In classic Raft, Ongaro recommends that for each read, the leader sends a message (an empty AppendEntries message specifically) to all its followers, checking that they haven’t seen a newer leader. The leader waits for a quorum of followers to reply before it runs the client’s query.

This is expensive, obviously—reads now pay the same network cost as writes—so commercial Raft implementations often use timed leader leases instead, or else they just don’t guarantee linearizability.

Unfortunately, the “Rethink” authors don’t seem to know about the deposed-leader problem at all. They claim to guarantee linearizability, but they don’t mention which, if any, technique they use to prevent reading from a deposed leader. I’ll come back to this topic and see if the paper can be saved.

Read Acceleration #

As I said, in classic Raft, the leader sets a query’s read index to its commitIndex, then waits for lastApplied to reach the read index. The “Rethink” authors want to reduce this waiting period. Their ideas for this are the best part of the paper.

Immediate Read: The leader immediately runs the client’s read, and buffers the result. Then it applies the log entries between lastApplied and the read index to the result, and returns the updated result to the client. This is faster than just waiting until the applier thread applies these entries to the whole state machine, as in classic Raft, because the buffered result is small, and because the leader can ignore entries irrelevant to this result.

Figure 9 from the paper.

For example, let’s say x is zero in the current state machine, and the client sends get x to the leader. The leader has these committed and unapplied log entries:

x := 9

z := 1

z := 7

The leader runs get x on the current state machine and creates the buffered result, x == 0. It applies x := 9 to the buffered result before returning it, and ignores the entries that modify z.

Semantic-Influencing Request: Sometimes, the Immediate Read fixup process is impossible. Let’s say the client sends a SQL query like:

SELECT * FROM table WHERE x = 1

The leader runs this query and buffers the resulting rows. Now it looks in its log and sees a committed and unapplied log entry like:

UPDATE table SET x = x + 1

The buffered result has the wrong rows! It includes all the rows where x was 1 when the leader received the query, but these are not the rows where x is 1 after running UPDATE. The leader can’t fix this up as easily as the previous example. The authors call this UPDATE a “Semantic-Influencing Request.” If such a request appears in the pending log entries, the leader could try something fancy like editing the original query before running it:

-- Change the filter from x = 1 to x = 0.

SELECT * FROM table WHERE x = 0

This query selects rows that will match the client’s query, after the UPDATE is applied. The authors say the leader should estimate the cost of fixing up the query, versus waiting until it can be run normally, and act accordingly.

Interaction of read and write optimizations #

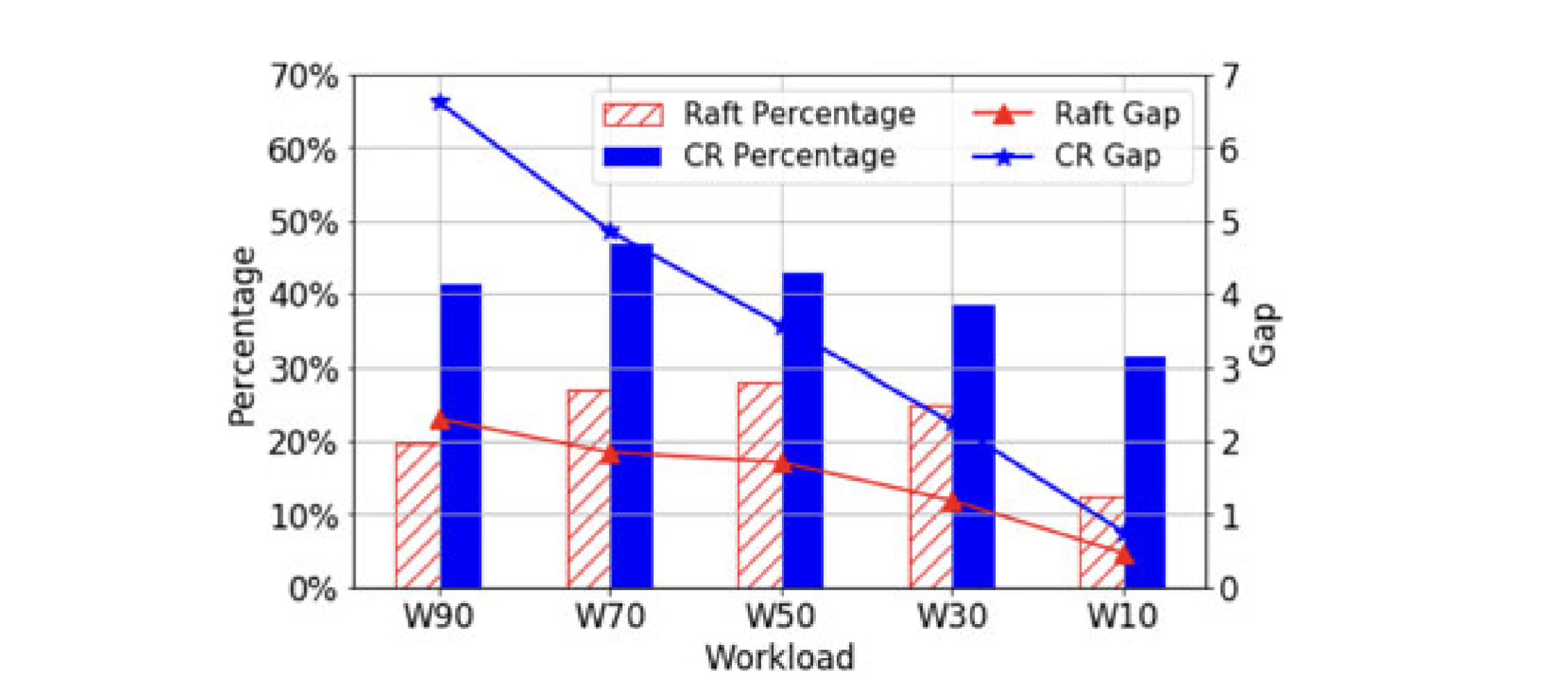

The authors say that Commit Return speeds up writes, but may slow down reads in exchange, because faster writes lead to a larger gap between the leader’s commitIndex and lastApplied. They even have a chart:

The red bars are the percentage of read latency in classic Raft that’s due to waiting for lastApplied to catch up to the query’s readIndex (which was the commitIndex when the query arrived). The higher blue bars are the percentage with Commit Return. The blue/red line shows the average gap between the readIndex and lastApplied with/without Commit Return, measured in number of entries. The horizontal axis is the percentage of writes in the YCSB workload, from 90% writes on the left to 10% writes on the right.

The authors claim this chart shows that with Commit Return enabled, there is a bigger gap between the leader’s commitIndex and lastApplied. This is an unfortunate mistake. I’m certain that Commit Return has no effect on the gap or on query latency. The authors were led astray by YCSB.

Commit Return merely reduces write latency from the client’s perspective: if the client does a blind write, the server replies “ok” a bit sooner, and the client can move on to its next task. If the client is a closed loop, then it waits for each request to finish before it starts the next. Let’s say this is the client’s code:

while True:

result1 = do_request("set x := x + 1")

result2 = do_request("get x")

In classic Raft, set x := x + 1 doesn’t return until the leader applies it, so the leader can run get x without much waiting. (If other clients submitted writes that are committed and unapplied when get x arrives; the leader still has to wait until those entries are applied before running get x.)

With Commit Return, set x := x + 1 returns as soon as it’s committed. Thus when the client sends get x, the gap between the leader’s commitIndex and its lastApplied is bigger than without Commit Return.

It’s important to understand that Commit Return doesn’t delay the advancement of lastApplied, so it doesn’t increase the gap between commitIndex and lastApplied in general! It just returns control to the client sooner, so the client can send a higher throughput of blind writes, or start querying sooner after sending a blind write. This only matters if you’re benchmarking the system with a closed-loop workload generator like YCSB. YCSB lets the server exert backpressure on the client, so it doesn’t measure throughput or latency realistically. (This is called the coordinated omission problem.)

A closed system.

With a more true-to-life open-loop workload generator, Commit Return does not have this effect. The authors’ claim that Commit Return makes Read Acceleration more important is a misunderstanding based on this obsolete benchmark.

An open system.

Tragically, lots of distributed systems researchers still use YCSB, so I see this mistake all the time. Worse, I see reviewers, who should know better, requesting that authors add YCSB benchmarks to their evaluations. YCSB benchmarks are wrong. If you’re a researcher, please switch to an open-loop workload generator, or invent one for the rest of us to use. If you’re a reviewer, point out this mistake when you see it. Let’s all standardize on some modern, open-loop benchmarks.

What about deposed leaders? #

The authors’ optimizations reduce latency and maintain linearizability, if the leader isn’t deposed. How do they guarantee that it isn’t?

If the leader checks a quorum of followers for each query, as in classic Raft, that gives the leader more time to concurrently apply any pending writes. It’s still possible that lastApplied hasn’t caught up to the readIndex during the quorum check—the authors constructed a scenario where applying commands is slow and communication is quick—but Read Acceleration is less useful once we take the quorum check into account.

The better way to handle a deposed leader is with a timed lease. I think the Read Acceleration techniques could be useful when paired with leases. I just hope anyone who reads this paper keeps the deposed leader problem in mind.

Conclusion #

This paper is a worthwhile read, despite its flaws.

Con: I doubt that it often takes longer to apply commands than replicate them, as the authors claim.

Pro: Even so, the Commit Return optimization might be a useful idea sometimes.

Pro and con?: Commit Return doesn’t have the downside the authors think it has: they think it makes reads slower, but that’s only in the artificial environment of a YCSB benchmark. Commit Return is better than they realize.

Con: The authors’ protocol does not guarantee linearizability unless they deal with deposed leaders somehow, like with a lease.

Pro: Read Acceleration is a cool idea. It’s useful if there’s a big gap between commitIndex and lastApplied. I really don’t think this is a common scenario, but the idea has other uses. I just published a paper in SIGMOD, with my colleagues Murat Demirbas and Lingzhi Deng, that uses a similar mechanism to permit linearizable reads when there might be multiple leaders.

Images: