Versions of The Eternaut

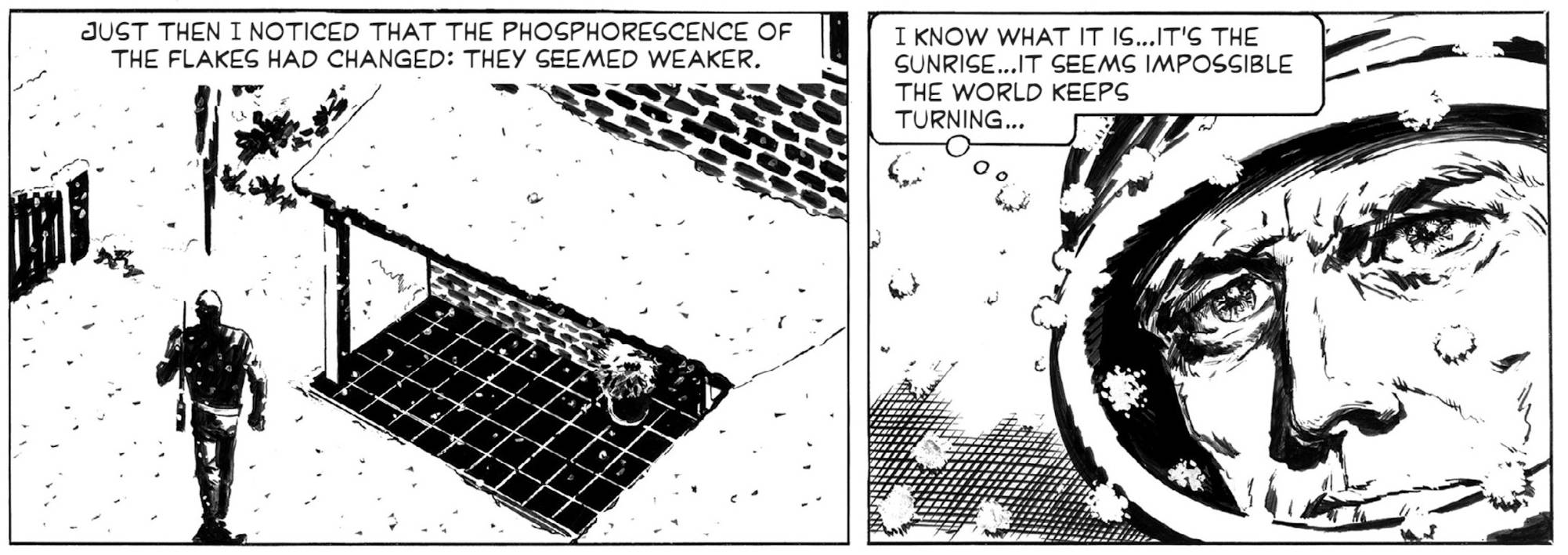

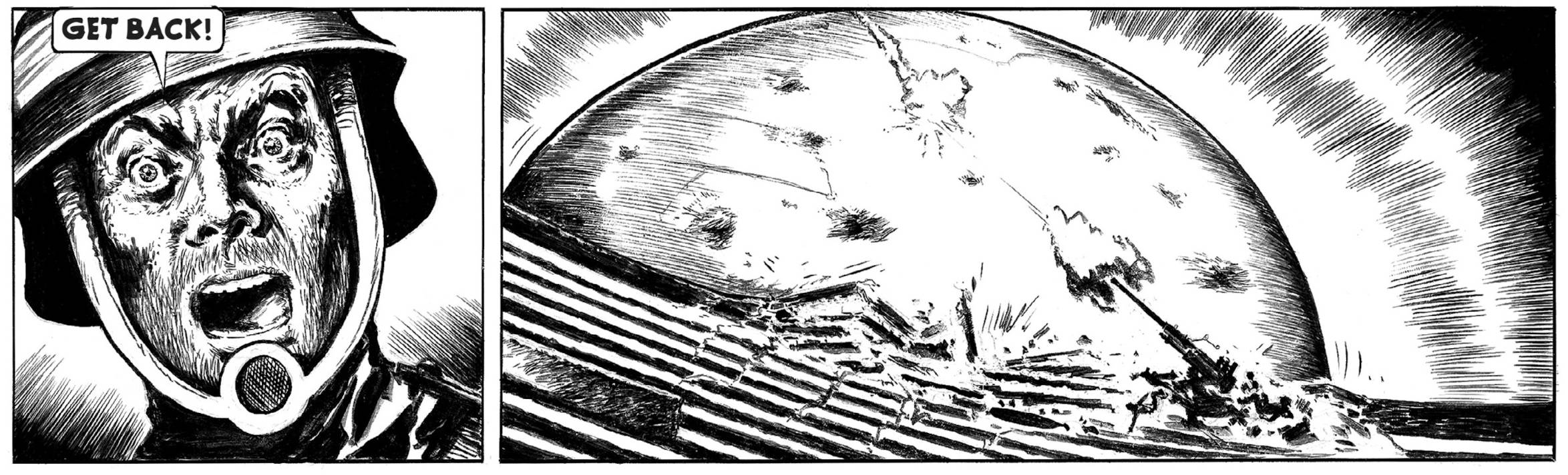

In late-1950s Buenos Aires, on a quiet night, Juan is in his attic, playing cards with his close friends. The radio plays in the background. Juan’s wife and daughter are downstairs. On their suburban street, snow begins to fall. The music on the radio turns to static. Out the window, Juan sees cars crashing, pedestrians dropping dead: the snow is glowing, toxic, everyone it touches dies in seconds. It’s the prelude to an alien invasion. Juan’s family and friends are lucky: the windows were all closed, and Juan’s modern house is tightly sealed. They fashion hazmat suits from spare parts and venture out to gather supplies for their survival.

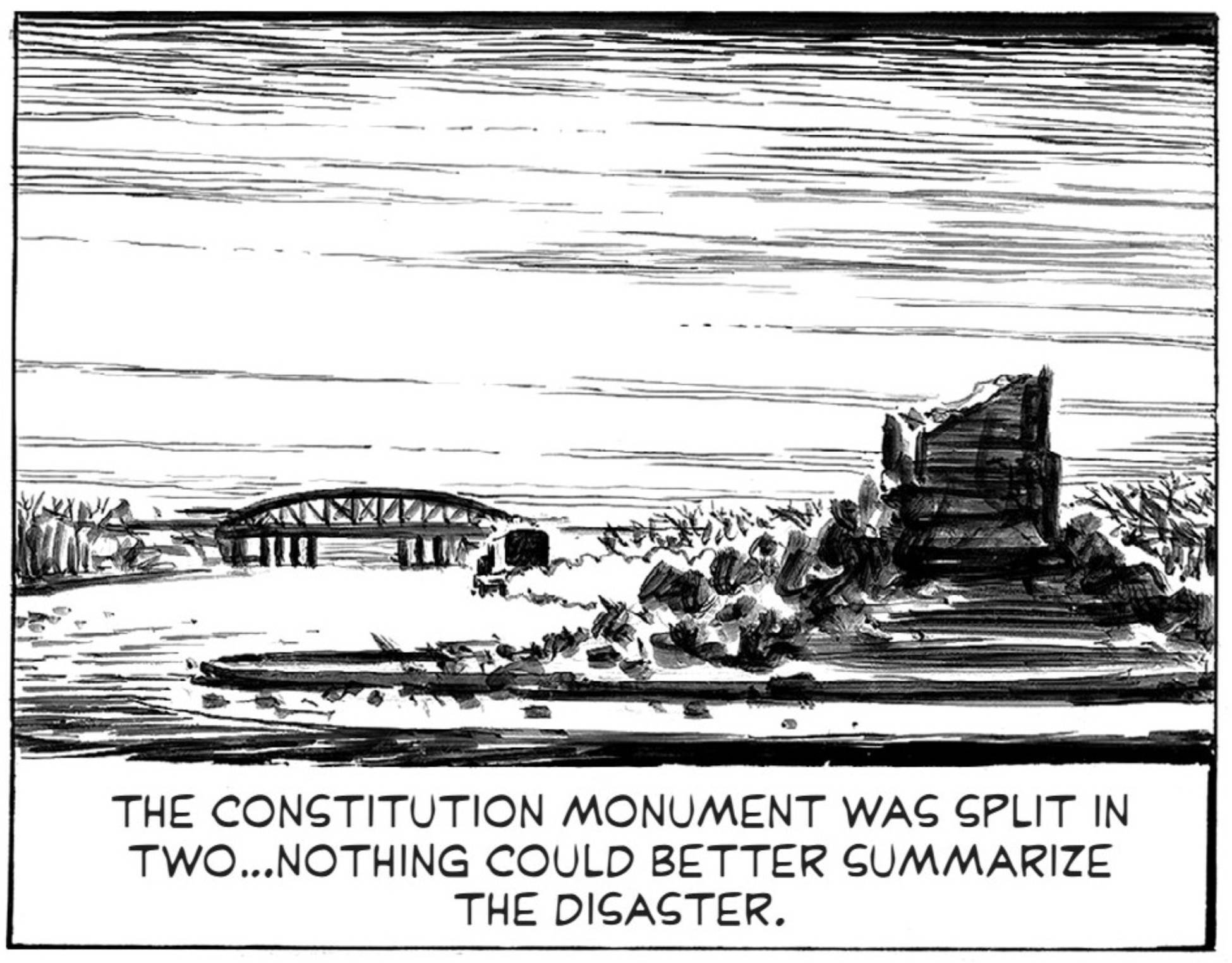

Over the next few days they’ll witness mass death, anarchy, waves of attacks by various weird aliens and crazy weapons, the destruction of the Argentine army, and perhaps the end of humanity. In the story’s final moments, Juan tries to steal an alien ship, but presses the wrong button and gets teleported to another dimension, doomed eternally to wander space and time, searching for his wife and daughter.

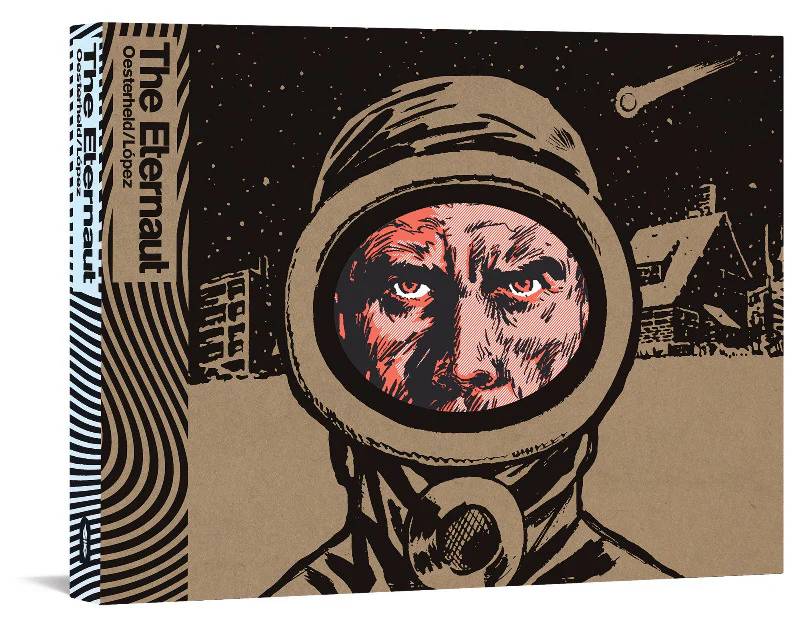

The Eternaut (El Eternauta in the original Spanish), written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld, was serialized in an Argentine sci-fi magazine from 1955 to 1957. It’s drawn by Francisco Solano López in a pulpy style, though with more artistic brushwork and composition.

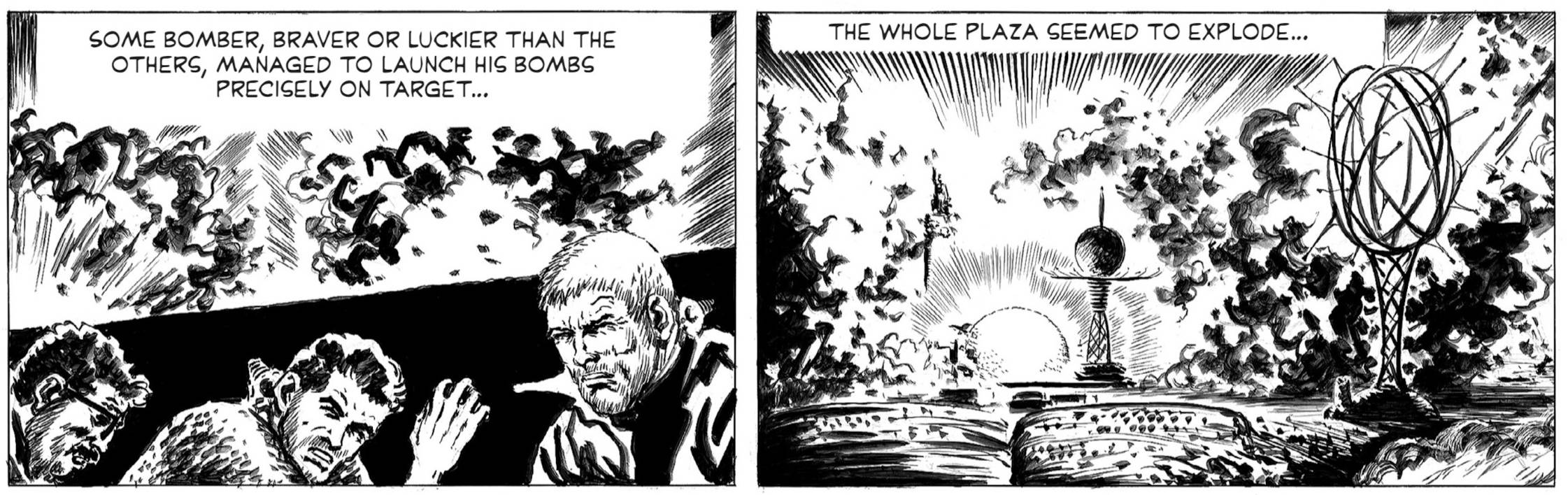

Oesterheld wrote the story in the aftermath of Juan Perón’s overthrow and an airstrike against a pro-Perón rally in Buenos Aires’s central square, which killed hundreds of civilians. I don’t know much about Argentina’s history, and I’m confused about Oesterheld’s opinion of Perón and the coup. Everyone has to agree that the bombing of the Plaza de Mayo was an atrocity, I assume. But in The Eternaut, it’s the good guys who bomb a plaza, trying to destroy the alien headquarters.

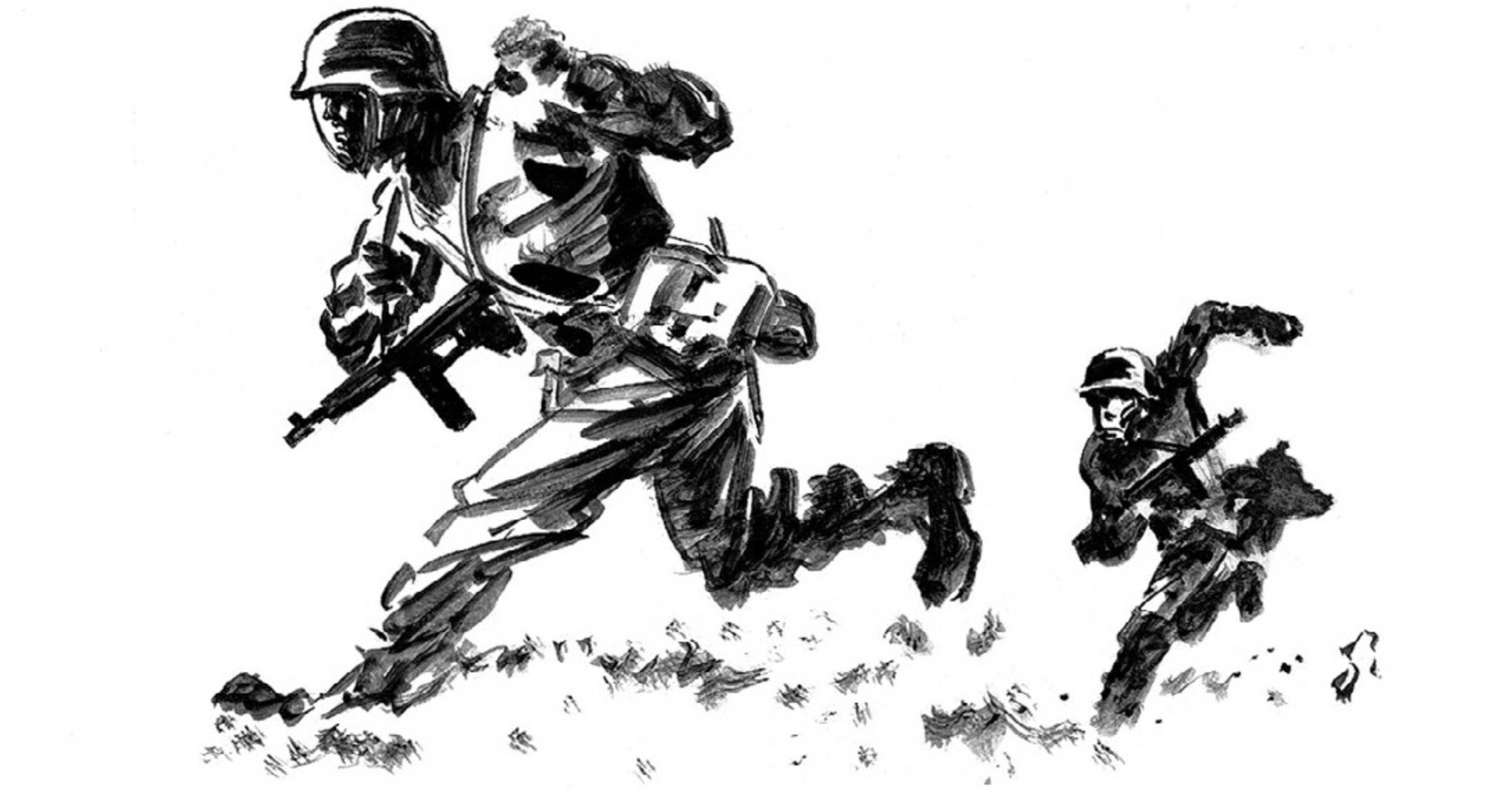

The themes of The Eternaut seem universal enough to be reused by any political faction. On one side of the conflict is a classic 50s hero, a square-jawed family man, with his brave and competent friends, a physicist and a metalworker. On the other side, inhuman and implacable enemies who bombard Buenos Aires with toxic snow and lasers, then use mind-control devices to enslave the survivors. They could represent the military forces that bombed civilians and overthrew Perón, or the repressive regime that followed, or the foreign imperialists who tried to manipulate Argentine politics from afar, or any foe of middle-class liberal patriotism.

The comic was published in installments, and you can see the seams between them when reading it as a book: each episode begins with a bit of recap and ends on a cliffhanger. Too many times, a major character is presumed dead and reappears improbably. But the story is among the most gripping I’ve ever read. The alien assault is relentless, the velocity of events is frantic and disorienting, the body count is in the billions, and the only predictable plotline is that all human resistance will be crushed. The story’s end is abrupt and shockingly inconclusive. We never actually see the invaders, or know for certain why they attacked and what they will do with the handful of survivors, if there are any.

Eternaut 1969 #

In the 60s and 70s, Oesterheld moved left. He wrote biographies of Che Guevara and Eva Perón, and a book titled 450 Years of War Against Imperialism, and sequels to the Eternaut, which I hope are translated to English someday. Meanwhile, Argentina descended into its worst era of dictatorship and violence, known as The Dirty War. Oesterheld and his family joined a rebel group. He was “disappeared” and presumably killed by the government around 1977.

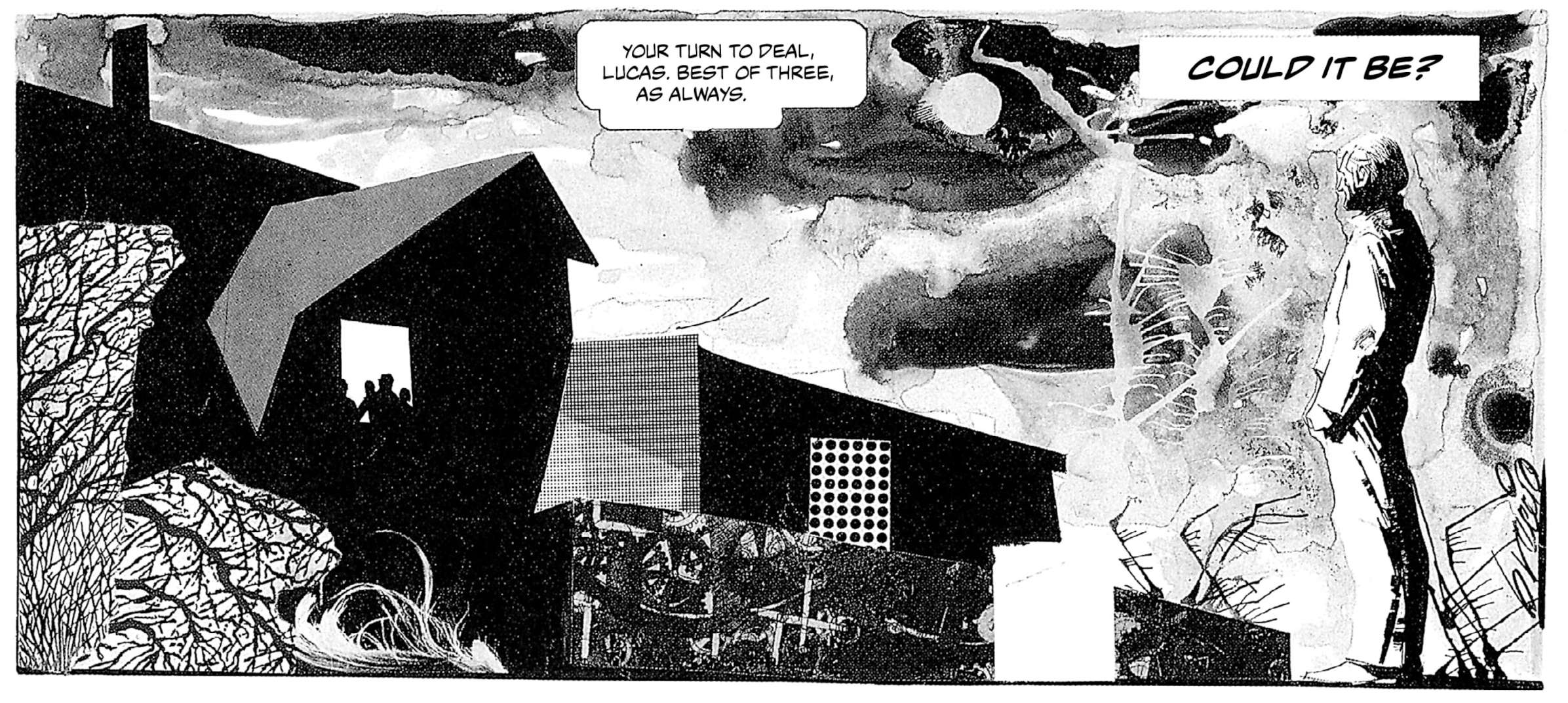

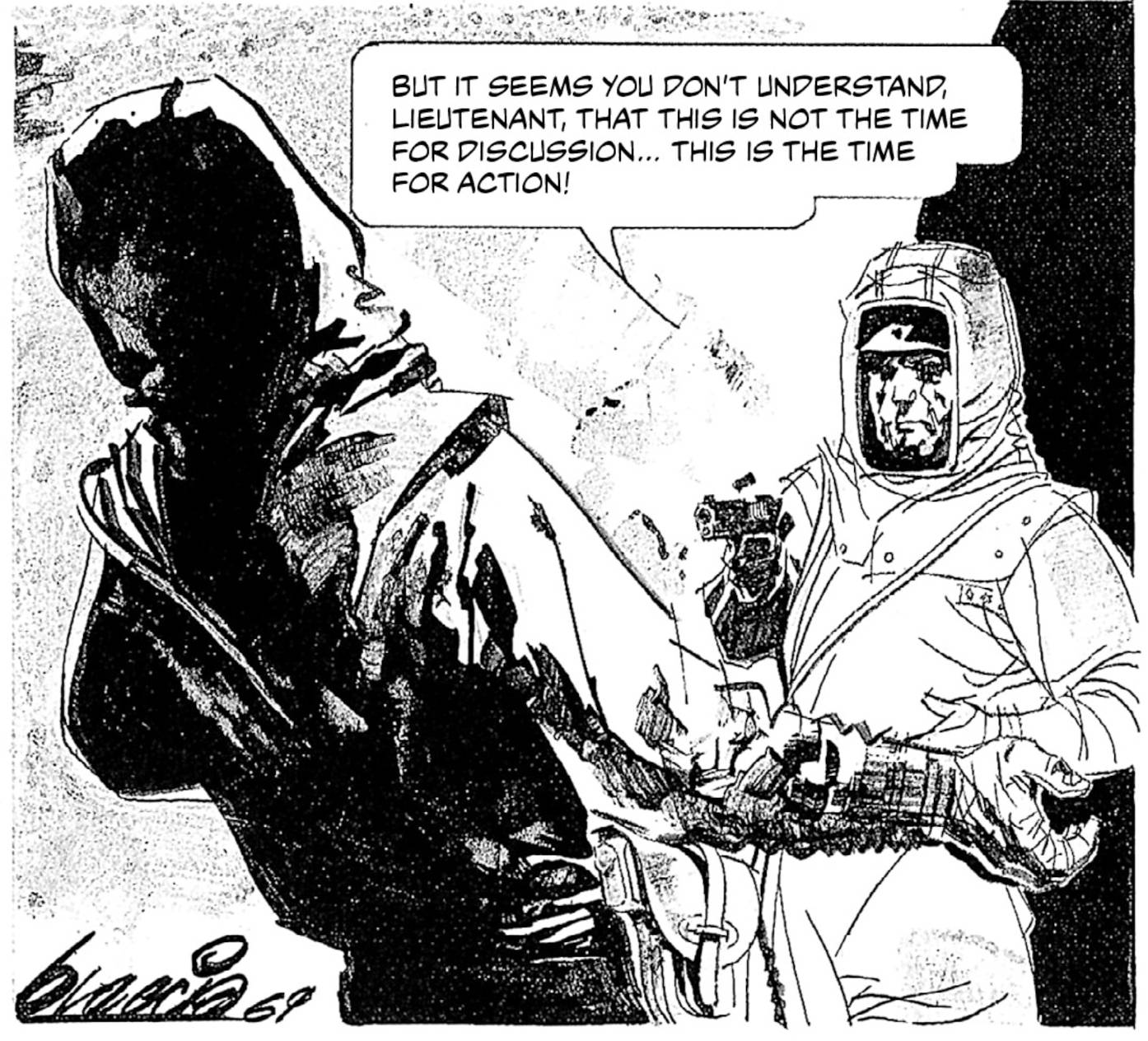

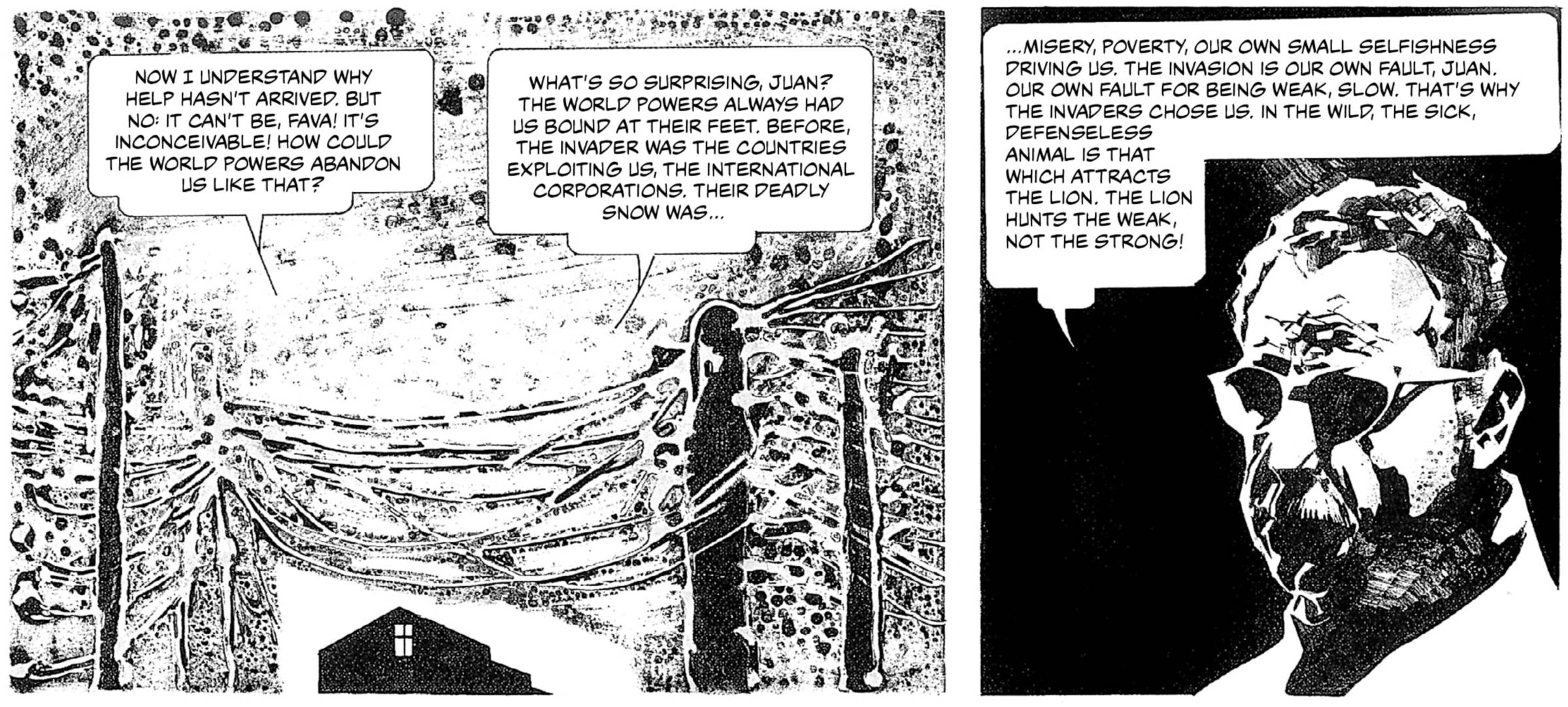

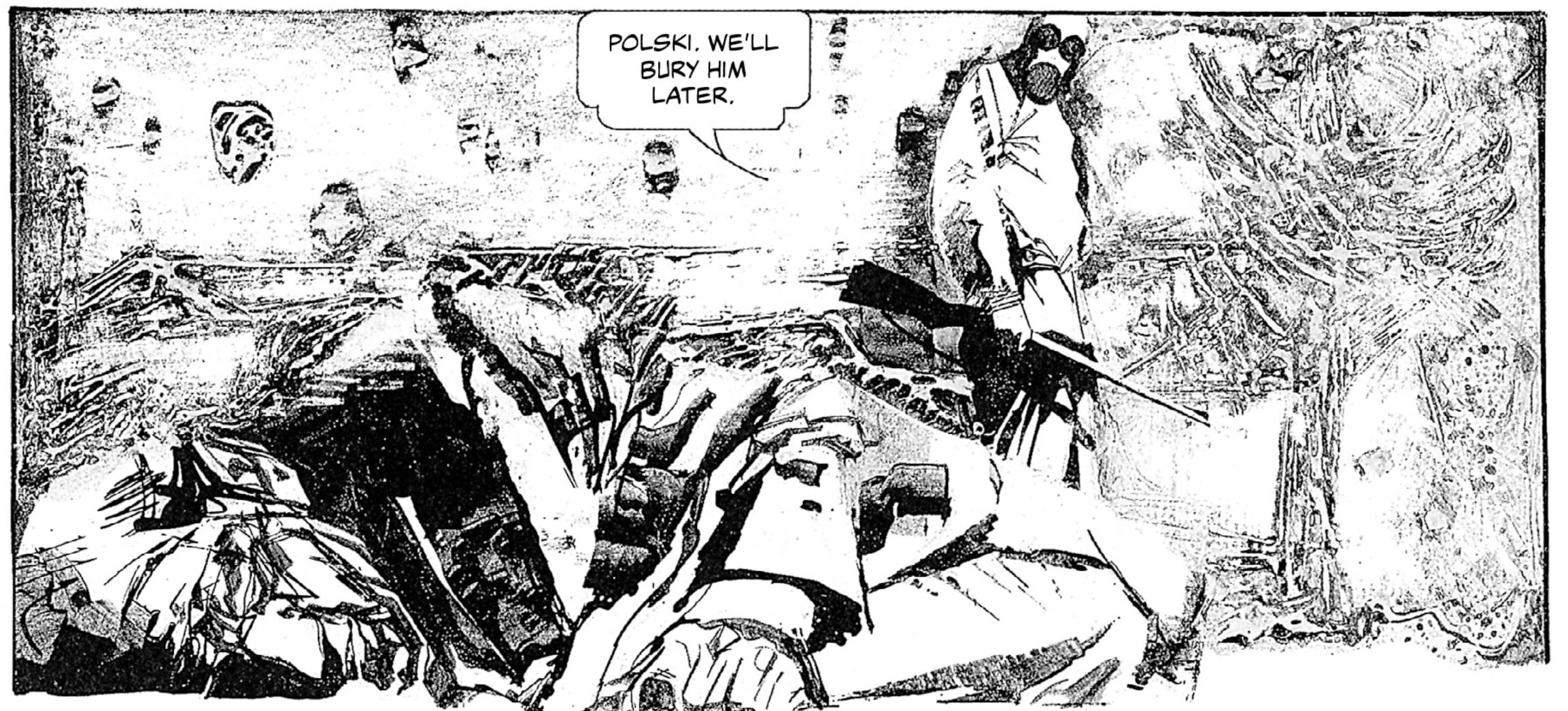

In 1969, Oesterheld rebooted the Eternaut with a new artist, Alberto Breccia, serialized in an Argentine gossip magazine. Breccia’s art is like a bad ayahuasca trip. Weird shapes and gloopy lines fill the background, the characters’ faces are lost in murk, the action is often illegible.

The content has darkened, too. In the 1950s, Oesterheld’s main characters are a plucky band of friends, and the Argentine army is led by stoic professionals. In 1969, everyone is paranoid. Juan observes that as soon as they rescue a young woman, the men see each other as rivals for her. The army is led by a brute who murders his lieutenant for dissenting.

In the original Eternaut, “the North” is a distant ally attacking the aliens with nuclear missiles. In the reboot, the northern powers have negotiated a separate peace with the aliens and abandoned the South, without even a warning.

Eternaut 1969 alienated its audience. Oesterheld’s resentful politics and Breccia’s avant-garde art led to the series’s early cancellation. In the last few pages the comic rushes to its conclusion, summarizing the plot in a few paragraphs and some vague illustrations. The work is a sad failure, comprehensible or interesting only to an Eternaut completist.

The Eternaut on Netflix #

The original Eternaut and Eternaut 1969 were republished, including English translations, in 2015 and 2020. I think the Eternaut comics influenced Netflix’s superb TV adaptation of the novel Station 11: the Station 11 show includes images of people in improvised hazmat suits walking around snowy Chicago, and a knife fight with a hazmat-suited intruder, that seem more inspired by scenes in The Eternaut than by Emily St. John Mandel’s novel. Maybe Station 11’s success and the reissue of the comics led Netflix to greenlight a 2024 adaptation of The Eternaut. The first season aired last year, and another season is in production.

Oesterheld’s heirs required that any adaptation must be in Spanish and set in Buenos Aires. Netflix complied, but moved the action from the 1950s to the present day. The show has the luscious visuals, desaturated palette, stylish soundtrack, and tight plotting you’d expect from a prestige sci-fi series these days. It borrows and expands the ideas of the 1950s comic, combining them with the paranoid atmosphere of Eternaut 1969. Unfortunately, some of the original Eternaut’s attention to detail is lost. Oesterheld knew enough science to make the alien snow a consistent and believable phenomenon. His heroes, a band of can-do tinkerers, build various filters, respirators, and airlocks to survive. These are described with some specificity, in the Popular Mechanics spirit of the era. On Netflix, though, the snow seems to kill or spare people based on the writers’ mood and the needs of the plot. Oesterheld’s snow blocks radio signals, neatly isolating the main characters and driving the plot, whereas on Netflix the snow is accompanied by some implausible super-EMP that not only knocks out the power grid but drains cell phone batteries specifically, sparing old cars and flashlights.

I’m not mad that Netflix is unfaithful to the comic, though. We’ve had seventy years to add ideas and overtones atop the foundation Oesterheld laid. In that time, Argentina passed through several coups, dictatorships, republics, another Perón presidency, and finally a stable democracy. Some of the genres that Oesterheld drew from, like alien invasion and post-apocalyptic survival, were new in the 1950s and are well-developed today. Perhaps most important, we’ve all recently lived through a pandemic. Like Juan when he first saw the snow, we didn’t know if the disaster was natural or a bioweapon. Like him, we were trapped inside until we jury-rigged masks so we could venture out and gather supplies. We personally saw the camaraderie and paranoia, the selfishness and courage that humanity displays in such a crisis. The Netflix writers mixed all these ingredients into a bigger, more complex story than Oesterheld’s original.