American Religion in America's Time of Crisis

Audio only:

(Podcast subscription: https://emptysquare.libsyn.com/rss)

Ever since 2016, I’ve been reading about Reconstruction.

A little about the Civil War, too, and Abolitionists in the 1840s and 50s, before the war.

What I want to know is, what happens when there’s a political fight for the meaning of the United States? A fight to determine whether the meaning of this nation is freedom, justice, and life, or if its meaning is hatred and death? If ordinary party politics transforms into a fight like this, what happens next?

In 1860, Lincoln was elected. He was a Republican, they were the progressive party at the time, and Southern Democrats feared Lincoln’s election meant that slavery would be abolished soon. The South seceded, we went to war, and nearly a million Americans died.

That’s one kind of outcome to polarization. And what happens then? How do we ever return to democratic processes, to ordinary life? After the war, the Radical Republicans in Congress passed laws and constitutional amendments that forced Southern whites to respect the rights of freed Black people. 15 Black congressman and 2 Black senators were elected during reconstruction, and Black people held about 15% of state and local offices at the peak.

But white supremacy was only partly interrupted, and not for long. White northerners and the Republican party lost their passion for enforcing Black rights in the South. White Southerners staged coups, rebellions, and massacres to depose the progressive Reconstruction governments in their states.

In 1876, the presidential election ended in a tie. Republicans and Democrats made a deal: the Republican candidate would become president, but the last Union troops withdrew from the South, and white supremacy was restored under Democrat state governments. Black people were denied the right to life and liberty in the South for another century.

But you could imagine the editorials if this happened today. Hey, at least the country wasn’t so polarized anymore! At least civility was restored. Republicans and Democrats could talk to each other like human beings once again. So long as they were white.

I just read a new biography of Frederick Douglass, titled “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom”, by David W. Blight. I wanted to understand how Douglass’s passion for justice endured through the whole 19th Century, despite defeat after defeat.

He was born a slave in Maryland, probably in 1818, the property of a man named Thomas Auld. Thomas Auld’s sister-in-law taught Frederick Douglass to read at the age of 12. When Douglass was 19, he lived in Baltimore. His owner rented out Douglass’s labor as a ship caulker at the docks. Douglass met a 24-year-old free Black woman named Anna Murray. They fell in love, she scraped together the money for a train ticket to New York City, and he fled to freedom. Anna joined him in New York and they married immediately.

Douglass later wrote:

I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the ‘quick round of blood,’ I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.

That gladness and joy must not have lasted very long though. Four million Black people were enslaved in the South. Douglass wrote and spoke and preached for his whole life, first to abolish slavery, and then to enforce political and social equality for Black people, and finally when Reconstruction had failed and Jim Crow laws restored white supremacy, Douglass spent the last decades of his life, as both an advocate and a critic of the Republican Party, touring the country and thundering about the unfinished work.

What sustained him through a lifetime of struggle?

Douglass found religion when he was 13 or 14 years old in Baltimore. He met a Black preacher named Charles Lawson. Lawson was nearly illiterate, but he understood the Bible and he understood God. Douglass read the bible to Lawson. He said later that “I could teach him the letter, but he could teach me the spirit.”

Douglass began preaching while he was still enslaved, in Baltimore, at an African Methodist Episcopal Church there. After he escaped to freedom, Douglass became a preacher with the AME church. He spoke at churches and used Biblical analogies and quotations his whole life, particularly the prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah. Those prophets had condemned the Hebrews for their immorality and warned that they would suffer for their wickedness—you can see why Douglass was inspired by them.

When Douglass was 30 years old, 10 years after his escape, he wrote a letter to his old master, Thomas Auld.

The very first mental effort that I now remember on my part, was an attempt to solve the mystery—why am I a slave? I had got some idea of God, the Creator of all mankind, the Black and the white, and that he had made the blacks to serve the whites as slaves. How he could do this and be good, I could not tell. I was not satisfied with this theory, which made God responsible for slavery.

One night while sitting in the kitchen, I heard some of the old slaves talking of their parents having been stolen from Africa by white men, and were sold here as slaves. The whole mystery was solved at once. From that time, I resolved that I would some day run away.

The morality of the act I dispose of as follows: I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons. What you are, I am. You are a man, and so am I. In leaving you, I took nothing but what belonged to me.

This passage is amazing, its compassion:

The responsibility which you have assumed is truly awful, and how you could stagger under it these many years is marvelous. Your mind must have become darkened, your heart hardened, your conscience seared and petrified, or you would have long since thrown off the accursed load, and sought relief at the hands of a sin-forgiving God.

I intend to make use of you as a weapon with which to assail the system of slavery—as a means of concentrating public attention on the system, and deepening the horror of trafficking in the souls and bodies of men. I entertain no malice toward you personally. There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other.

I am your fellow-man, but not your slave.

Right here is the whole answer for today. Douglass is both compassionate and angry, both forgiving and uncompromising. He picks his weapon and rushes into the battle for justice.

Ever since 2016, I’ve been wondering what American Buddhists can do about America’s crisis. When I look at the old sutras or the koans they’re not much help to me. The Buddha didn’t have any project to reform ancient India’s politics. Within his own sangha he abolished caste, and women were closer to equality than they were in the surrounding society. But the first sangha didn’t participate in local politics. Internally, the monks and nuns had a wonderful political system: they followed an omniscient guru. Whenever they had a policy question, they asked him, and he told them the answer immediately, in excruciating detail, in verse.

What about our Chinese ancestors of 1300 years ago? They lived in a time of great political turmoil and civil war, but we don’t read about how they voted, or ran for office, or marched in protests.

Political participation is a somewhat modern idea. Reforming society is a modern idea. Some people have found inspiration for today from the ancient texts. The whole Buddhist Peace Fellowship and the Engaged Buddhist movement includes many people who apply the old stories to today’s situation. But right now, I’m finding more inspiration from American religion in the abolitionist era. That’s our lineage, too, as American Buddhists, we descend from them, just as much as we descend from Asian monastics.

We can look back at abolitionists like Benjamin Lay, a Quaker. Shinryu Sensei gave a terrific talk about him a few years ago. I recommend the biography, called The Fearless Benjamin Lay.

We can look to Frederick Douglass, who preached in the African Methodist Episcopal church. The Congregationalist minister Henry Ward Beecher, who raised money to buy slaves’ freedom, from a church in Brooklyn. William Lloyd Garrison, who founded the Liberator newspaper and the American Anti-Slavery Society, was inspired by the writings of a Presbyterian minister. Oberlin College, where I went, was one of the first co-ed and integrated colleges, the first in the US to graduate a Black woman, was founded by radical Protestants. The whole abolitionist movement in the United States was led by Quakers, Unitarians, Methodists…. And of course religious leaders and religious groups were in the vanguard of the peace movement, women’s rights, and the civil rights movement of the 20th Century, too.

Imagine if they had said religion and politics don’t mix.

Not all American Buddhists think we have a responsibility to engage in politics. I do. My partner Keishin and I have hosted a fundraiser for Joe Biden, we’re sending texts and postcards to voters, we’re doing everything we can. I asked a Buddhist friend if he’d help me raise money for Biden, and my friend wrote back:

I personally do not find a political appeal in accord with Buddhist practice. I am aware there are practitioners who hold the opposite, but I have found it’s usually because they have put their worldly goals above enlightenment in the name of compassion for others.

Yeah, I do have worldly goals in the name of compassion. That’s why I’m a member of the Village Zendo. Enkyo and Joshin founded this group in the midst of the AIDS crisis, with their fellow activists. This sangha is both a place for traditional Zen practice, and a foundation for activism. In the time I’ve been a member we’ve marched against war and against climate change, we’ve marched for a $15 minimum wage, we held vigils outside the governor’s mansion for clemency and prison reform. That’s my kind of Buddhism and it’s why I joined this sangha 17 years ago.

You might think that because the Buddha preached the Middle Path, we shouldn’t pick sides. That’s not what he meant by the Middle Path. In the oldest sutras, the Middle Path avoids the extremes of ascetism on one side, self-indulgence on the other. In Mahayana sutras, the Middle Path avoids the extreme of believing in an eternal soul, on the one hand, or believing that existence is an illusion and nothing is real, on the other. In our school, the Middle Path is “Not Knowing”. On the one hand, we don’t have any fundamentalist dogmas. On the other hand, we do have opinions. It’s my opinion that if Trump wins another four years, we risk great suffering and death.

The Buddha preached the Middle Path, and he also preached the precepts. Don’t lie, steal, or kill. In a democracy, we are responsible for our nation’s lying, stealing, and killing. There’s no escaping this responsibility. Reforming our nation is practicing the precepts.

You might make a distinction between campaigning for causes, and campaigning for a candidate. This distinction is so recent. It comes from a 1954 tax reform bill. Lyndon Johnson, who was a senator at the time, added a provision that said tax-exempt religious organizations can’t campaign for or against candidates. This was 1954, the peak of McCarthyism, and Lyndon Johnson was trying to suppress right-wing religious support for McCarthyism.

This taboo on religious organizations campaigning, it’s not about the First Amendment, it’s not about the separation of church and state, it’s not fundamental to the American system. It’s a tax rule from 1954.

So, to be clear, the Village Zendo doesn’t endorse a candidate. Our board of directors didn’t encourage me to talk about politics, I’m speaking for myself. I have taken the Bodhisattva vow to protect all beings from suffering, and I have promised to uphold the Buddhist precepts which oppose lying, stealing, and killing. It’s clear to me that American Bodhisattvas should be using every one of our thousand arms to defeat Trump. If politics is an expression of our religion, we must have sacred means, not just sacred ends. We have opponents, but never enemies. We are passionate, but never violent. Like Frederick Douglass when he wrote to his old master, Thomas Auld, we must be immovable in our principles, but forgiving towards our fellow beings.

I do need to say that Douglass was not a pacifist. He said the moment he became a man was when he beat up a slave driver. In the 1850s he advocated killing slave catchers and slave owners. He quoted Isaiah, “There is no peace, said my God, to the wicked.” When the Civil War broke out, Douglass was ecstatic. He said that white supremacy would not be defeated unless Southern society was completely destroyed. As a forecaster, he was right—because Southern society was not completely destroyed, white supremacy did return. But as a Buddhist, I don’t admire this bloodthirstiness in Douglass’s thinking.

In 1877, after the war, after Emancipation and Reconstruction, when Frederick Douglass was 59, he went to Maryland to see Thomas Auld. He wrote later that this homecoming was strange enough in itself, but to see his former master was still more strange.

Thomas Auld was sick and bedridden. His hands shook. Douglass wrote that he sat by Auld’s bedside,

holding his hand and in friendly conversation with him in a sort of final settlement of past differences, preparatory to his stepping into his grave, where all distinctions are at an end, and where the great and the small, the slave and his master, are reduced to the same level.

One question that had nagged Douglass his whole life was what year he was born, was it 1817 or 1818. Auld told him right away that he’d been born in 1818. There’s another thing Douglass wanted to know—was Thomas Auld his father? He didn’t ask. No one knows why he didn’t.

Douglass wrote,

He was to me no longer a slaveholder either in fact or in spirit, and I regarded him as I did myself, a victim of the circumstances of birth, education, law, and custom. Our fates were determined for us, not by us. Even the constancy of hate breaks down before the brightness of infinite light.

God willing, we’ll have the opportunity to forgive, after this struggle. Buddha’s teachings, and abolitionist preachers like Douglass, can show us how. Let’s follow their example.

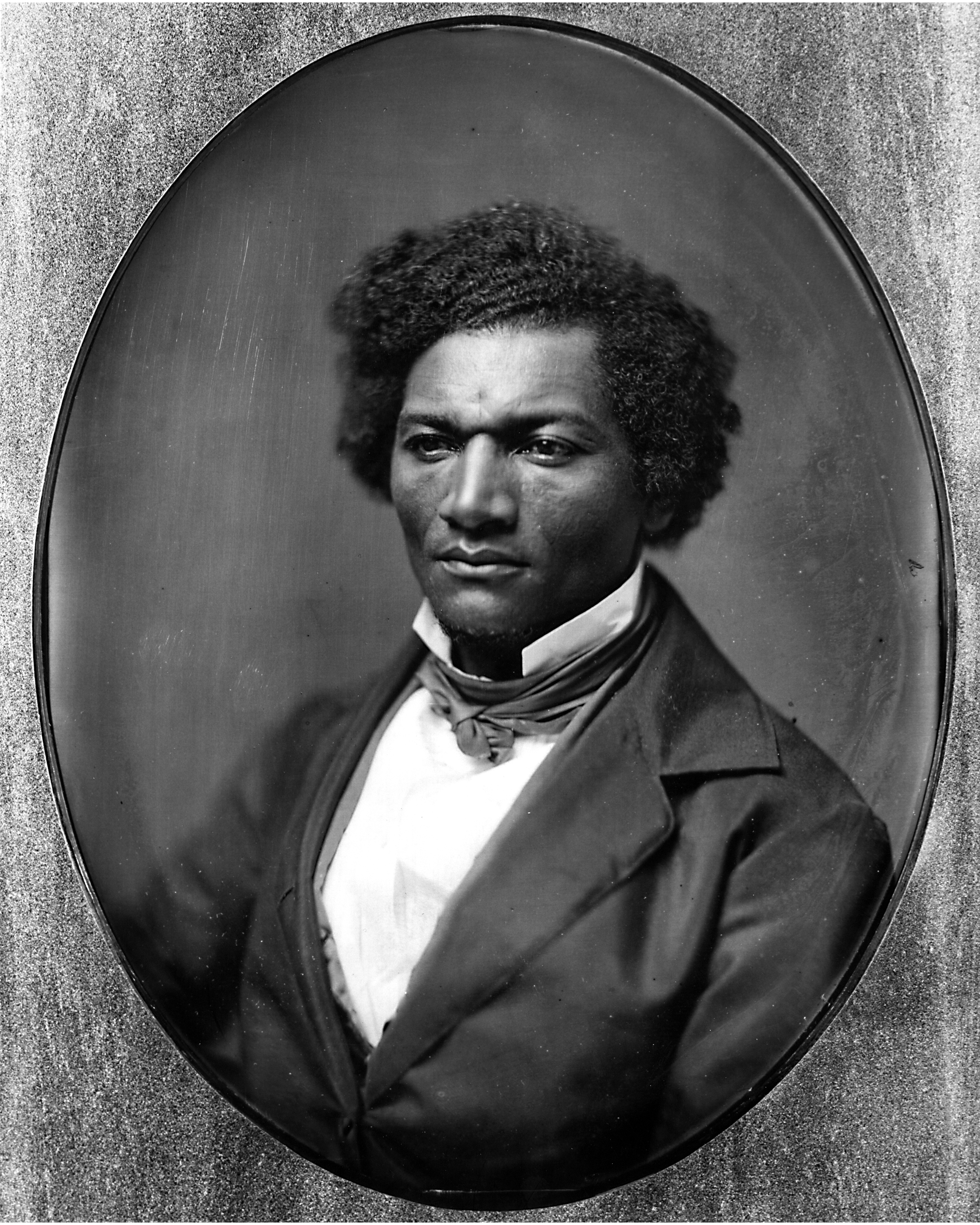

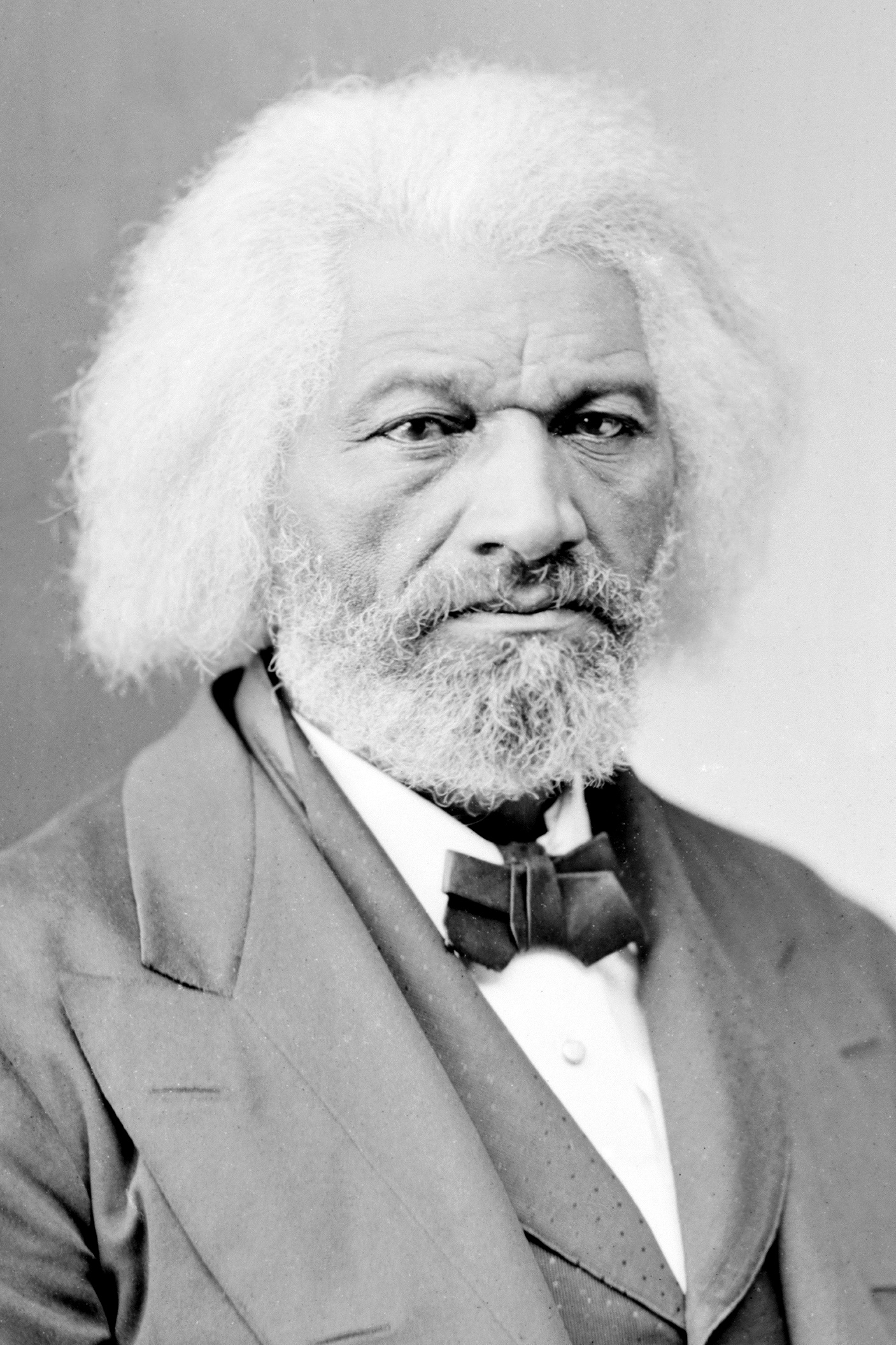

Top: Daguerrotype of Frederick Douglass, c. 1847-1852, by Samuel J. Miller. Bottom: Collodion plate of Frederick Douglass, c. 1865-1880, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection.