Arjuna's Dilemma

I look in the Bhagavad Gita and the life of radical abolitionist Benjamin Lay for examples: how do we live in stressful times, and how do we act when there are no good options? This is my March 30, 2025 dharma talk at the Village Zendo. Watch the video above, read the transcript below, or subscribe to my podcast.

TRANSCRIPT #

Once upon a time, ages ago, there was a civil war. One family, the Kurus, had ruled the great kingdom of Hastinapura for many generations, but there was a succession dispute, and relatives who had grown up together and loved each other became mortal enemies. On one side of the civil war were the Kauravas, 100 brothers miraculously born to the same mother at the same time, all strong and brave warriors. On the other side of the war were the Pandavas, 5 brothers, cousins of their enemies the Kauravas.

The middle child of the Pandavas was Arjuna. He was the greatest archer, perhaps the greatest warrior in history. He was a killing machine, he could shoot arrows with both hands at once, somehow, that’s what the story says though I can’t picture it. His quiver was inexhaustible, his aim was inescapable. But he was peaceful, humble, virtuous, never killed in anger and never committed an act of cruelty.

This story is the Mahabharata, of course, composed in India around 2000 years ago. It is the longest epic poem ever, it is 2 million words, I haven’t read the whole thing. I’m using some quotes translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, and by Stephen Mitchell. In the Ganguli translation, Arjuna was:

“Youthful in form, of curled locks and exceedingly handsome; embued with great energy and prowess; possessed of eyes like lotus-petals.”

“None can bear the prowess of Arjuna, who gratifies the fire by the slaughter of foes, like the wind scattering the clouds.”

So this guy—you’d expect him to have a nice life, right? Born a prince, handsome, intelligent, strong, brave, skilled, pious. When he sneezes, the gods shower him with lotus blossoms in celebration. He’s destined for success!

But he’s unlucky. He’s born into hard times. Because of the conflict between his brothers, the Pandavas, and his cousins, the Kauravas, he and his brothers lose their kingdom. They are exiled for 12 years. They grew up in this beautiful palace—now they live homeless in the forest. When they return, they try to regain their kingdom, first by diplomacy, and when that fails, by war.

I’ve been thinking about Arjuna lately, because I feel a little like him in my own small, non-epic way. I have a lot of privileges. But the last year has been hard. My mother’s been in and out of the hospital. There were moments we thought she might die—and moments we thought she should. She’s doing better now, but still, sometimes when she doesn’t pick up the phone, I panic a little.

And our poor hamster Sojourner has been bleeding internally for more than a month. We’ve been trying to treat her, but she’s not getting better. We don’t know what’s going to happen.

We’ve been building a house where we live in New Paltz. After we passed the point of no return—we had to finish it—the stock price of my company, which is where most of my money is, crashed. Now we don’t know if we can afford to finish the house, or what we’ll have to give up in order to do it. It’s just this daily poison of anxiety. It keeps me awake at night.

I lead the Zen program at Sing Sing Prison. A few months ago, the New York State prison guards all went on strike—illegally—in a disorganized way. The strike is supposedly over, but we don’t know what’s going on. Religious programs are still canceled. We haven’t been able to go in, see what conditions are like, support our sangha. Meanwhile, many prisoners have died due to the chaos and neglect. Not our sangha members. We don’t know what’s going to happen.

Of course, Trump and Musk are dismantling the federal government—or trying to. We don’t know what’s going to happen there either.

Like Arjuna, I’m not just an observer. I’m a citizen of New York State. I pay taxes to fund this dysfunctional prison system. I’m a citizen of the United States. I pay taxes supposedly to run the federal government. I pay for weapons that Ukrainians use to kill Russians. I pay for weapons that Israelis use to kill Palestinians. I pay for weapons that Americans use to kill Yemenis.

So I’m looking for the moment outside of Buddhism at examples like Arjuna. How do you live in difficult times? How do you appreciate your life? How do you take action—especially when there doesn’t seem to be a good option?

In the Mahabharata, the war between the Kauravas and Pandavas looks like it’ll be cataclysmic—a world war. Both sides are allied with many kingdoms. They gather armies of millions. On each side are a quarter million elephants, each with a driver and archers riding on top. On each side are half a million cavalry and a million infantry. These two stupendous armies line up on a huge battlefield, Kurukshetra. When they blow their conches, they can be heard from miles. The dust that they raise darkens the day. Their war cries make the ground vibrate, make their armor rattle.

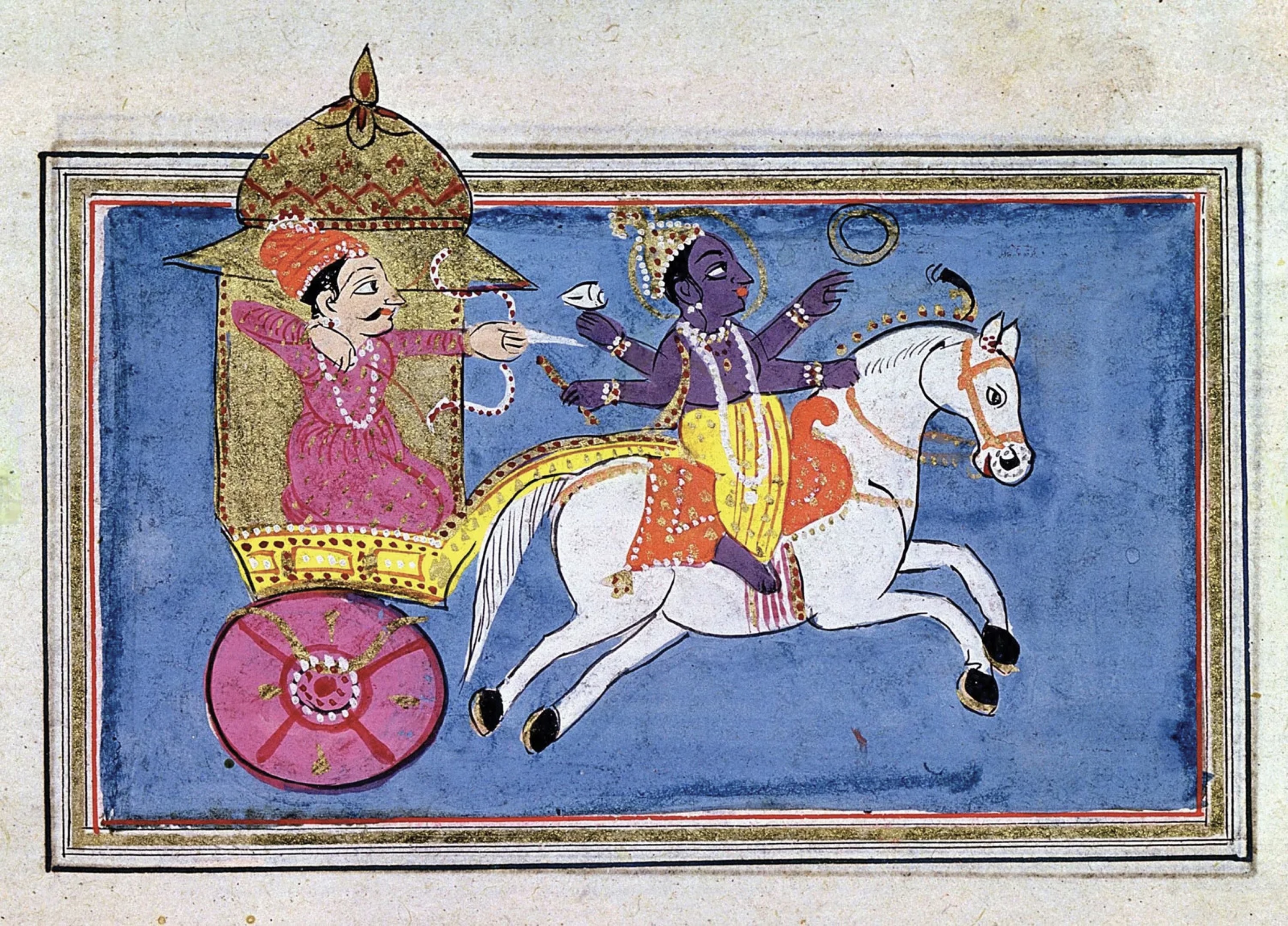

Arjuna is ready in his chariot, with his magic bow. The god Krishna is also participating—not as a soldier, as Arjuna’s charioteer. They drive into the middle of the battlefield, between the two armies, so Arjuna can get a good look at the other side.

He sees his own cousins. Friends, teachers, uncles. Millions of courageous soldiers on both sides prepared to destroy each other. And he hesitates.

As I see my own kinsmen, gathered here, eager to fight, my legs weaken, my mouth dries, my body trembles, my hair stands on end, my skin burns, the bow Gandiva drops from my hand, I am beside myself, my mind reels. I see evil omens, Krishna; no good can come from killing my own kinsmen in battle. I have no desire for victory or for the pleasures of kingship. What good is kingship, or happiness, or life itself, when those for whose sake we desire them—teachers, fathers, sons, grandfathers, uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons, brothers-in-law, and other kinsmen—stand here in battle ranks, ready to give up their fortunes and their lives?

The Mahabharata is not concise, as I said. Arjuna goes on,

Though they want to kill me, I have no desire to kill them, not even for the kingship of the three worlds, let alone for that of the earth. What joy would we have in killing Dhritarashtra’s men? Evil will cling to us if we kill them, even though they are the aggressors. And it would be unworthy of us to kill our own kinsmen. How could we be happy if we did? Because their minds are overpowered by greed, they see no harm in destroying the family, no crime in treachery to friends. But we should know better, Krishna: clearly seeing the harm caused by the destruction of the family, we should turn back from this evil. When the family is destroyed, the ancient laws of family duty cease; when law ceases, lawlessness overwhelms the family; when lawlessness overwhelms the women of the family, they become corrupted; when women are corrupted, the intermixture of castes is the inevitable result.

This is where things get weird and bigoted and we remember this is a 2000-year-old Indian poem.

Intermixture of castes drags down to hell both those who destroy the family and the family itself; the spirits of the ancestors fall, deprived of their offerings of rice and water. Such are the evils caused by those who destroy the family: because of the intermixture of castes,

He’s really into this.

…caste duties are obliterated and the permanent duties of the family as well. We have often heard, Krishna, that men whose family duties have been obliterated must live in hell forever. Alas! We are about to commit a great evil by killing our own kinsmen, because of our greed for the pleasures of kingship. It would be better if Dhritarashtra’s men killed me in battle, unarmed and unresisting.

He drops his magic bow. Slumps to the floor of the chariot.

Krishna sees that his friend is in trouble. Right there in a chariot parked in the middle of the battlefield, between two armies about to destroy each other, they stop. The battlefield falls silent. On this ground that’s about to be soaked with the blood of millions, Krishna explains everything.

This part of the poem is special. It’s called the Bhagavad Gita, the god’s song. Krishna says to Arjuna,

Nonbeing can never be;

being can never not be.

Both these statements are obvious

to those who have seen the truth.The presence that pervades the universe

is imperishable, unchanging,

beyond both is and is not:

how could it ever vanish?These bodies come to an end;

but that vast embodied Self

is ageless, fathomless, eternal.

Therefore you must fight, Arjuna.

Now this is a Hindu text, and we’re in a Buddhist temple, and we’re going to see that Hindu teachings and Buddhist teachings have some differences. Krishna says that everybody is part of one eternal universal Self, an Atman. This Self, the Atman, survives the death of the body, and it returns to the Great One. He says,

If you think that this Self can kill

or think that it can be killed,

you do not well understand

reality’s subtle ways.It never was born; coming

to be, it will never not be.

Birthless, primordial, it does not

die when the body dies.Knowing that it is eternal,

unborn, beyond destruction,

how could you ever kill?

And whom could you kill, Arjuna?

Compare this to Buddha’s teaching. Buddha lived a few hundred years before the Bhagavad Gita was composed, but in Buddha’s lifetime as well, Hindus believed in this Atman theory, this eternal Self. Buddha rejected this. He taught the radical idea of Anatman, Non-Self. He said that there’s nothing eternal, and there’s no distinction between body and soul. Everything is transformed. Everything is always being recycled now.

You and I are just a tunafish can and a La Croix can, on the great conveyor belt to the recycling center of the universe. We briefly have different flavors, but it’s all going in the fire. It will all be melted down. It will all come back as a hubcap or a roll of aluminum foil. And when we die, there is no soul that gets separated and returns to the Great One. It all goes in the fire. It is all recycled.

Buddha believed in reincarnation, of course, but the person being reincarnated is like the tin of the tuna can, or a wave that goes down into the ocean and then comes up again, or a flame that flickers and passes from one candle to another candle. It’s part of the environment. It’s always changing. And eventually it will be extinguished.

Another difference is Buddha taught his followers unequivocally: do not kill. Neither Self nor Non-Self excuses killing. If you kill, you’re going to make bad karma. It’s going to stick to you, whatever you are, it’s going to doom you to thousands of suffering rebirths.

But what Krishna says next to Arjuna, this could come straight out of Buddha’s mouth. Krishna says,

You have a right to your actions,

but never to your actions’ fruits.

Act for the action’s sake.

And do not be attached to inaction.Self-possessed, resolute, act

without any thought of results,

open to success or failure.

This equanimity is yoga.Action is far inferior

to the yoga of insight, Arjuna.

Pitiful are those who, acting,

are attached to their action’s fruits.The wise man lets go of all

results, whether good or bad,

and is focused on the action alone.

Yoga is skill in actions.The wise man whose insight is firm,

relinquishing the fruits of action,

is freed from the bondage of rebirth

and attains the place beyond sorrow.When your understanding has passed

beyond the thicket of delusions,

there is nothing you need to learn

from even the most sacred scripture.

Act for action’s sake. Nothing to learn from scripture. This is starting to sound like Zen, isn’t it?

So Arjuna’s doubts are resolved. He sees that he has a part to play in the endless destruction and recreation of the universe. His role is a warrior, so his job is to fight. That’s his dharma. Dharma is the most overloaded word in Sanskrit. For Hindus, dharma means your role, your duty. Maybe Arjuna wishes he were born to be a cook or a poet. But he’s not. His job is to fight and the time to fight is now.

So off he goes and he mows down his cousins.

There’s Arjuna and Krishna in a chariot on the left side, and Karna—the champion of their enemies—on the right. They’re all looking calm. But in between, on the line of battle, everybody’s spurting blood.

Here’s a medieval sculpture: Arjuna is on the right now, machine-gunning arrows at Karna.

That’s Arjuna’s story, but the Mahabharata includes a note of dissent. A minor character named Balarama.

He’s a god, of course—the half-brother of Krishna. And he sounds awesome. He’s fantastically strong in battle, and he fights with a plow. See how he’s holding a plow in this painting. He’s also an expert with a mace. He teaches mace fighting to one of the Pandavas and one of the Kauravas, these two cousins, years before the war. When these two students end up on opposite sides of the war, Balarama is heartbroken. As the armies assemble on the battlefield, Balarama says to his half-brother Krishna:

Let us render assistance to the Kurus.

Meaning: let’s help the whole family, not one side or the other. The poem says:

Krishna, however, did not listen to those words of his. With heart filled with rage at this, the wielder of the plow set out on a pilgrimage.

Balarama pleads with Krishna—maybe pleading with him to help stop the war? Krishna, the wise and omniscient one, ignores him? So Balarama hits the bricks. He’s outta there. He takes his whole clan with him, too. He’s fed up with his brother. He wants no part of the war. He goes off on a pilgrimage, and we don’t see him again until weeks later, when the battle is nearly over.

In all the Mahabharata’s hundreds of thousands of lines of poetry, we get three lines about this argument between Balarama and Krishna, about what Krishna actually should be doing about this world war.

So whose action was right in this awful moment? Krishna is the hero of the Bhagavad Gita, there’s no question about that. I’m not going to argue that Balarama’s side is secretly the message of the poem. Krishna’s message in the Bhagavad Gita is sacred scripture for Hindus. But I’m glad that Balarama’s viewpoint got a few lines.

In 2006, I took the precepts and got the name Jiryu, and I promised not to kill.

At the time, we were at war in Iraq and Afghanistan. We were torturing people in CIA black sites and Guantanamo. Israel was bombing Lebanon with American cluster bombs. Cluster bombs are big bombs, and as they fall, they break up until lots of little bombs. And then they all hit the ground and explode. So obviously there’s no targeting. And almost every time, a few of these bomblets are unexploded. Long after the war is over, some kid is playing in the rubble and gets blown up. For this reason all civilized countries have banned cluster bombs, but the U.S. and Israel still use them.

This for some reason, was the straw that broke my back, and I decided to stop paying federal income tax, so I wouldn’t pay for war. Not because I didn’t want to pay for the government—I’d have checked a box if I could that said “yes, I’ll pay for all the nonviolent programs.” But I couldn’t. So for me, the only way to uphold the precept of not killing was to stop paying. Every year I filled out my 1040 accurately. I enclosed a letter explaining that I’m a Zen Buddhist, can’t pay for war. I redirected all that money to charity. I couldn’t work a regular W-2 salaried job, because my employer would withhold my taxes and pay them for me, so I went freelance, changed jobs every few months.

I’m a computer scientist, and before I started tax resistance, I was working on big interesting problems. I was trying to use software to identify students who were struggling so that teachers could do targeted interventions, intensive tutoring, help them catch up. As a freelancer, I couldn’t take on a big project like that, so I ended up making iPhone apps. I made one for recording Little League scores, which is fine. And one for the Star Magazine celebrity gossip app, which is not fine. It’s toxic mental bilgewater. So to uphold non-killing, I violated the precepts of “don’t give intoxicants” and “don’t discuss others’ errors and faults”, right? I made a platform for gossip.

There is never ever any purity. Never ever.

So in 2011, after I’d been not paying for four or five years, I approached a startup, a database company in New York City, doing really interesting work, and joined them. And I still work for them today. There’s a lot of compromises in that, working for a company. We have defense contracts. We have intelligence contracts. I and other employees have objected to this, but we’re overruled. But on the other hand, we also power the British health service, and we power the Indian national ID system, which is the biggest social welfare, anti-corruption success story of the 21st Century. And of course, I had to pay all of my federal income tax back with interest, and a lot of that paid for war.

I think I made the right choice, but morality is not an equation. You can’t balance it. You can’t see which side is bigger. You’ll never really know.

So I’m still searching for examples. Who can I emulate?

The other non-Buddhist example is Benjamin Lay. He was a Quaker, a writer, a dwarf, and a radical activist against slavery.

He was born in England in 1682. As a young man, he made a nuisance of himself, telling his fellow English Quakers that they were too greedy and in love with luxury. When they spoke in meetings they claimed to be inspired by God, and he told them that in fact they were just in love with their own opinions and conceited about their own performance.

Dharma talkers, take this to heart.

He married another English Quaker, another dwarf named Sara Smith. They moved together to Barbados to set up shop. Barbados was an English colony, and the economy was booming because of the sugar plantations, worked by enslaved Africans. Benjamin and Sara Lay witnessed the worst carnage of slavery, and a lot of it was perpetrated by their fellow Quakers. Once, they went to visit a friend, and outside his house was a man hanging from a tree, naked. Benjamin wrote later that below the enslaved man’s “trembling and shivering body” was a “flood of blood.” Sarah went inside and asked the Quaker slave owner, what the hell? And he said he was punishing the slave for running away for two days.

Benjamin and Sarah held meetings of enslaved people at their home in Barbados. They served meals and they talked about ending slavery. This was obviously unpopular with the local whites. They left, Benjamin and Sarah, to escape the hostility, probably the eventual violence, of the slave owners. And also because they feared that if they stayed in Barbados any longer, they would be complicit with the slave economy. Maybe their hearts would be hardened. They would become used to this cruelty.

They became passionate abolitionists. Ending slavery, and particularly ending Quakers’ complicity with slavery became Benjamin’s life work. Sarah died in 1735 and it seems like once Benjamin was no longer worried about the consequences of his actions on Sarah, he became more radical and more fearless. Once in 1742, he staged a bit of street theater. He went to the marketplace in Philadelphia, and on a table he laid out fine china tea cups and saucers. (This might have been Sarah’s inheritance. We’re not sure.) He took out a hammer, and one by one smashed each saucer and tea cup.

I’ve been reading a lot of history and I’m starting to understand better just how insane this looked to everybody around him. Fine china for an 18th-Century middle class family was the store of wealth. It was the most expensive thing they probably owned. It doesn’t go bad. It doesn’t fall apart. It’s better than money. It’s better than real estate. This is how people were financially secure, and he was taking it out and smashing it.

Eventually some young men ended his performance: one guy grabbed him and another guy grabbed the china and ran away with it. But Benjamin’s point had been made: tea is harvested by colonized Asians who are brutally exploited, and sugar is made by enslaved Africans in the Caribbean who are worked to death. And the whole British empire’s economy is integrated. You can’t drink tea and not be a part of this, not be complicit.

Benjamin wanted to live without exploiting any other creature, not an enslaved person, not a colonized person, not an animal. In the final years of his life he’d become as self-sufficient and non-exploitative as possible. He had moved into a cave in Pennsylvania. He had vegetables that he grew himself, and honey from bees that he kept himself. His clothes were flax. He didn’t want to wear wool, he didn’t believe in exploiting sheep, or cotton, obviously: that was cultivated by enslaved people. So he grew flax, spun it, wove it and made his own clothes with it. He never rode a horse, he walked everywhere.

But his life in the cave was not a hermitage. He had visitors. He read books and he wrote pamphlets and he wrote a book.

Here’s Benjamin in front of his cave. He’s got his clothes that he made himself. He’s holding a book. He’s got a basket of vegetables that he grew and his walking stick, so he doesn’t have to ride an animal.

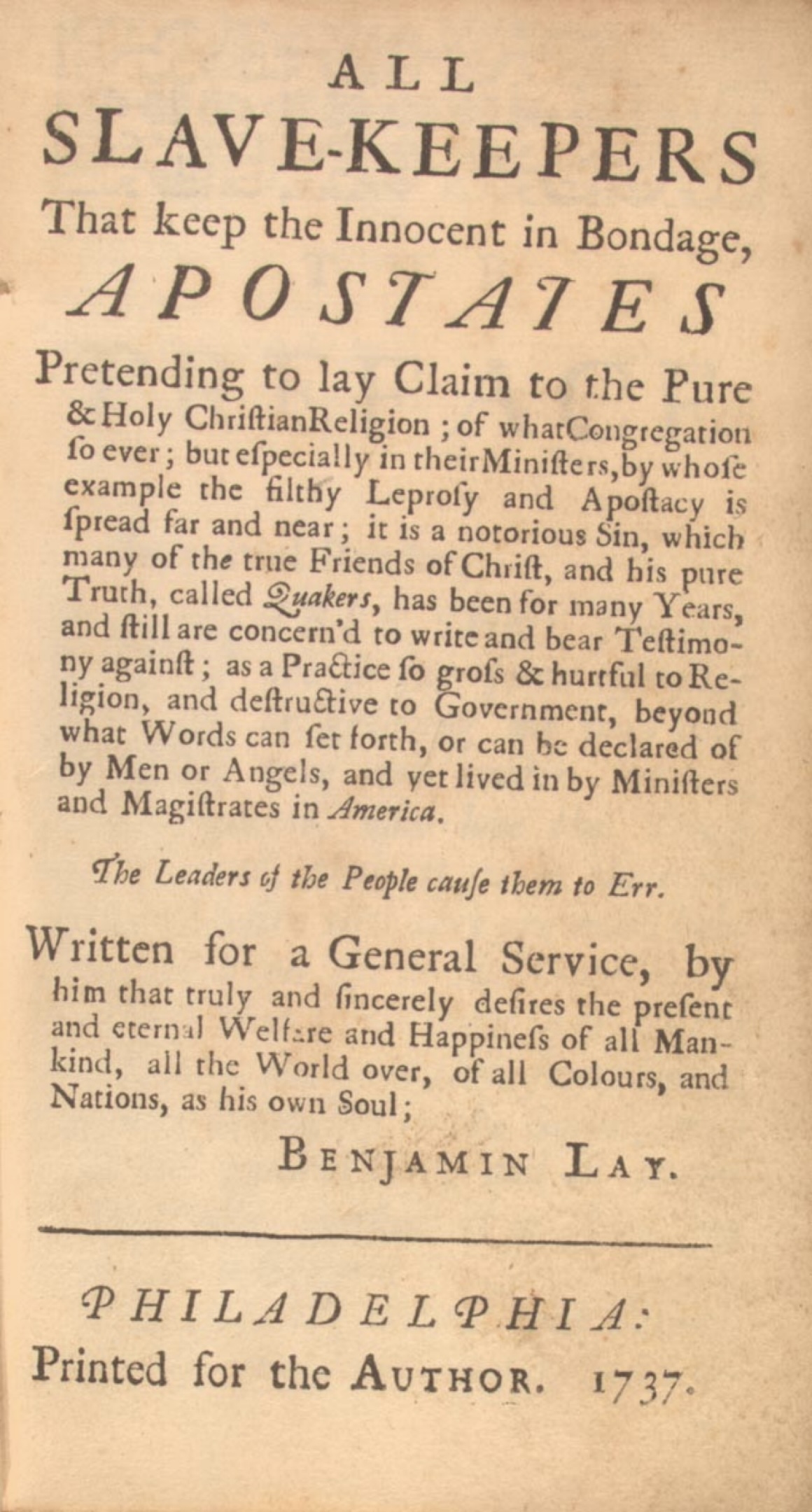

And his book, “Slave Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates”, meaning heretics, meaning anybody who claims to be a Christian but enslaves his fellow humans is a heretic. This was published by Benjamin Lay’s friend, Benjamin Franklin. But Franklin was too cowardly to put his name to it as the publisher.

I first heard of Benjamin Lay when Shinryu Roshi talked about him in 2017. Shinryu talked about him because the historian Marcus Rediker had just published a biography of Benjamin Lay, kind of bringing him back from obscurity. The biography is titled “The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist”. I’ve read it, I recommend it. And he’s coming to my mind again because I just saw a one man play called The Return of Benjamin Lay. It’s co-written by Marcus Rediker and it stars Mark Povinelli. It’s great, it’s short, it’s only $65, it’s playing a few blocks away through April 7th and I recommend it.

So my objective was to look for tips for living and taking action in difficult times. How can we be happy? How can we choose the best among bad options?

Arjuna, on Krishna’s advice, fulfills the role that he finds himself in, even if he has to fight his family. He does it without anger or cruelty. He’s not attached to the outcome. He just focuses on skillful action.

Balarama walks away, goes on a pilgrimage, doesn’t want any part of this, comes back when the fighting’s over.

Benjamin Lay also refuses to participate in violence, but he doesn’t walk away. He stays engaged. He argues and eventually he wins. In 1758, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Quakers, this kind of administrative body, bans slave trading by all Quakers, and 18 years later, bans slave holding. Of course, slavery continues in the American colonies and the United States for a hundred years. Benjamin Lay continued to be an inspiration to abolitionists here and in England.

I can’t just imitate one of these people. So I have two principles that I’m trying to keep in mind. First is, I intend to enjoy my life, no matter what. I don’t believe in reincarnation; I believe in YOLO. There isn’t going to be some other life that’s going to be easier to appreciate than this one. Of course there’s going to be conundra and Catch-22’s and difficulties in my life. But I’m going to enjoy it anyway.

Second, I intend to act effectively. If it seems like there’s a march or a donation that’s actually going to make a difference, I’ll give it a shot. Nothing’s certain. I’m going to concentrate on things that seem to have a high probability of success. I donate to GiveWell, which measures charities’ effectiveness and directs money mostly to poor countries. I’ll write to my New York State officials and ask what is going on with the prison system. We need it stable and humane and non-violent and we need to restart religious programs. I’m not going to refuse to pay my federal taxes again. It’s not the right message for this time. I don’t know what I’m going to do about Trump and Musk yet. I do live in a swing congressional district with a Democratic congressman who keeps barely winning reelection. I helped him win last time, I’ll help him win next time.

Beyond that, like Aaron Burr sings in “Hamilton”:

I’m not standing still,

I am lying in wait.

Whenever the moment for action arises, I will take it.