How To Dissolve The Self

Transcript #

I can stand 25 feet above the floor on a little piece of plastic the size of my big toe and not be afraid.

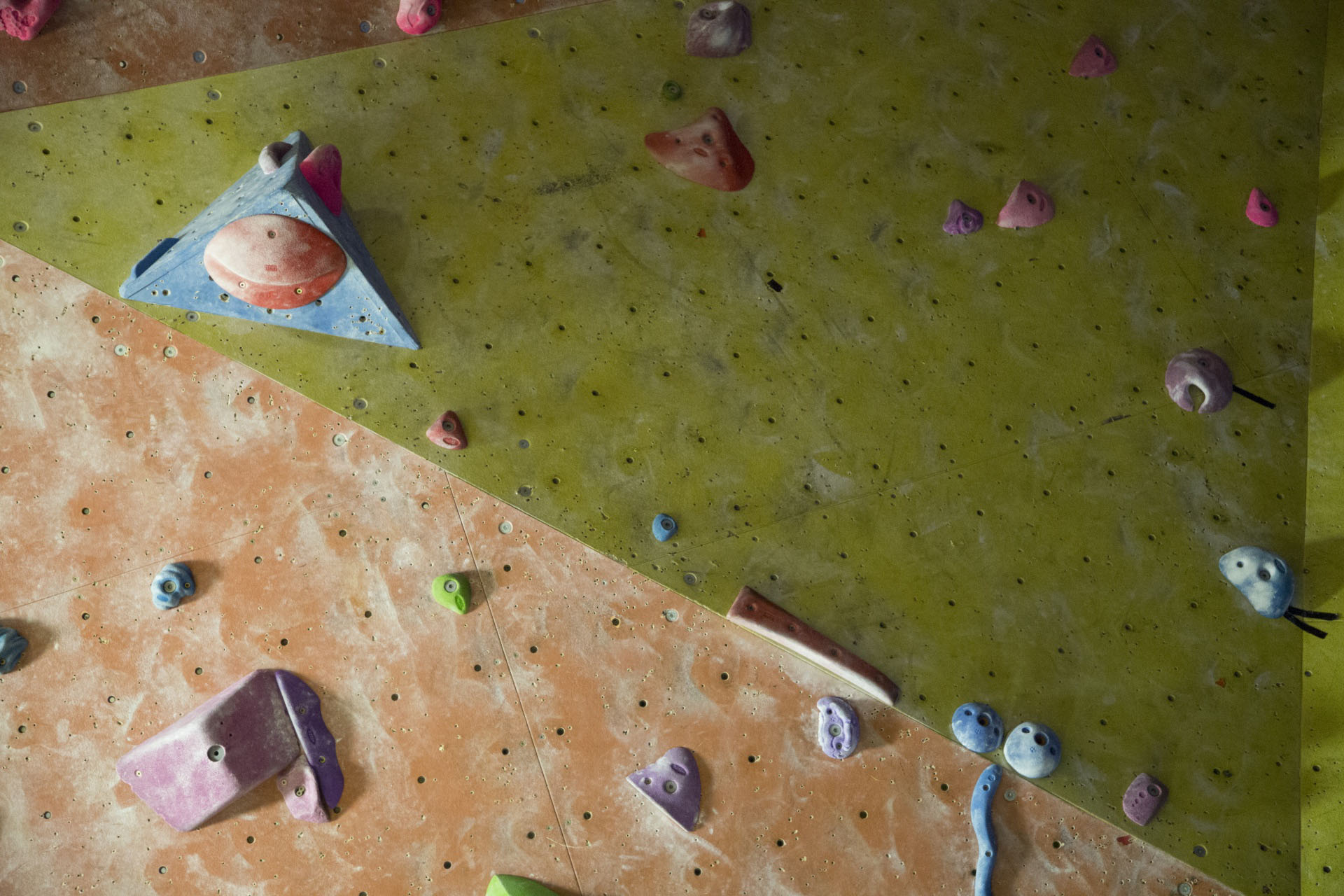

But this is something that I’ve worked up to. My partner Keishin and I have been going to a climbing gym. We started early this spring. It’s in Long Island City, and if you’ve never been in an indoor climbing gym before, it’s this enormous room with walls 45 feet tall, and the walls are uneven. There’s great slabs that lean back or hang out into the room over you. There’s corners that jut out or fold in.

The route-setters who configure the climbing gym are continuously putting up routes on these walls made of these colored plastic holds that are all different shapes and sizes and textures. So there might be a route up one section of wall that consists of all green handholds and footholds. And that might last for a little while and then they’ll unscrew all of the holds and put in a new route with different holds there.

One of my favorite experiences so far at the gym was the first time that I climbed a particular yellow route. It was rated 5.9 which is, on the scale of things, not very hard. A medium-amateur grade of difficulty. But it was the tallest and the most difficult climb that I had attempted so far.

The climb started with about 25 feet of vertical wall with these plastic hand- and footholds. And that part of the section is not that bad. Some of the holds only have one good side that you can hold onto, so you have lean your body over to the other side in order to be able to hang off of them with your fingers wrapped around them. But that was okay. I’d been climbing a couple months. I knew how to handle that. It just tired me out a little bit by the time I’d reached the 25-foot mark. Then things got really dicey, because there’s a chunk of wall that comes straight out horizontally into the room.

So, picture what it would take to climb up the side of a house. You go up the vertical wall on the side of the house and then when you reach the point where the roof meets the wall, and hangs out over the wall. You have to climb up into the eaves and then reach out over the gutter, and then swing one leg up over the gutter, and then the other. And then you can stand up on the roof.

That’s what how this wall was designed, except it was the size of, like, a five-story house. So when you get up to that 25-foot mark, you reach the roof, it’s hanging out over you. And you’ve got to, for a few moves, crawl up under that roof, hanging with your body horizontal—hanging by your fingers and your toes—and crawl backwards to the lip of the roof, in order to reach up over the edge of the roof onto the next section of all that’s above it.

You get one hand over and you find your handhold there. Your feet are still under the roof but one hand’s above it, and then you get your other hand over the lip. So far, so good, but then the really scary part comes when you have to swing one leg up over that lip and make that transition: instead of pressing your foot into this stalactite that’s hanging down from the roof, you have to swing your foot up over and place it on this tiny little yellow piece of plastic that claims to be a foothold but it’s the size of a thimble. It’s right on the lip, so below the little yellow plastic thimble is 25 feet of thin air. You have to place your foot on top of it and then really step on it, shift your weight over onto that little thimble and stand up, and trust that it will protect you from falling 25 feet through the void. The first time I tried this, I was just so afraid, and shaking so bad, that I just—I couldn’t do it, and I fell off.

And it was completely safe, because I’m attached to the rope, and the top of the rope is attached to the top of the wall, and the other end of the rope is attached to Keishin who’s standing on the floor below me and keeping this rope ratcheted tight. When I fell, I fell about one foot. And then Keishin gently lowered me the rest of the way. So it’s completely safe, but try telling that to your body. Your body will take that information with a grain of salt.

The next time I tried it, I managed to get my weight onto that thimble and stand up, but by that point I’d been gripping the holds so hard out of fear that I was completely exhausted, and my hands gave, and I fell off again.

So I came back a few days later and I got my foot on the thimble, I stood up on it, and I managed to make the next few moves and climb the remaining 20 feet to the top of the wall.

That was so exciting. That was such a moment of pride for me. I was laughing as I was lowering down on the rope, I was so excited. My hands were tired and I needed help to undo the rope tied to my waist, but I’d done it.

For the next few weeks every time we would go back to the gym, I would save time at the end to do that same yellow 5.9 route again. And I got better and better at it, and I got less and less afraid. It was like a pride spigot that I could keep going back to for more. Every time I wanted to feel good about myself, no matter what had happened previously in the session, even if I’d fallen off every single route that I’d tried, I would make sure that I did that one at the end, so I could walk away feeling good about myself.

Then one day we went to visit the gym and the route was gone. The route setters had re-set that whole section of wall, they had unscrewed all of the holds from the wall, and put up new routes. There was something purple there that was much harder and I had to start over from scratch figuring out how to climb that route now.

That ability that I’d achieved for myself was suddenly irrelevant. The fact that I could climb that particular yellow 5.9 turned into a memory and began to vanish. I was a better climber than I’d been before, but my ability to climb that route was suddenly meaningless.

This is what happens to all our achievements, right? Sooner or later. If we try to make them part of our identity—I am somebody who can do this—it vanishes, it turns into just a memory, and then a ghost, and disappears.

Things that I’ve achieved at past jobs, computer code that I wrote? Those companies went under. The code was lost. Nobody remembers what I did. It’s gone.

Things I achieved as a teenager, like being cool for a second, I no longer care about. I worked so hard for it and it’s not an achievement at all, because my values changed.

Think of something you were proud of that’s vanished in some way. How do you deal with that? What does your identity do in response when something that you had, amoeba-like, tried wrap your identity around and hold, and then it just turns out to be a puff of smoke and is gone? How do we deal with that?

My identity is kind of like a wall that I build up around myself to try to give myself a sense of solidity and reliability, a sense that I’m a thing and I know what I’m going to be like tomorrow, because I built this structure around myself today. And the bricks in this wall that define my edges, they’re built out of the achievements that I’m proud of. They’re also built out of things that I’m ashamed of. I think those things are actually much better building material. The stuff that I’m ashamed of defines me. I use the things that I believe that I can do, and the things that I believe that I cannot do as bricks in these walls. Things that I believe are true. Things I refuse to believe. Things I like or don’t like. The goals that I have. All of these are these bricks that keep me solid.

Buddha taught—this is one of the earliest, most reliable things that we believe that he actually said—Buddha taught that this sense that we have that we are things that last, that are the same tomorrow as they are today, that we have this identity—it’s false. It’s a delusion. And it leads to disappointment because we think that we are a thing which we can add good things to and reject bad things from. We can get more of the stuff that we like and we can remove the things that we don’t like, and so the thing-of-myself will be better tomorrow. But none of this lasts. At all. So it’s disappointing, and this leaves us permanently dissatisfied and stressed out, unhappy with our lives.

In the Sattipatthana Sutra, Buddha taught a meditation to remind us that our bodies won’t last. So, imagine a fit, beautiful, Peleton-trained body. And then imagine that it’s a corpse. It’s blue, swollen and festering, and then it’s being eaten by crows, hawks, vultures, dogs, jackals or by different kinds of worms. Then it’s a skeleton, held together with some flesh and blood and tendons, and then it’s just a blood-smeared skeleton with all the flesh gone, but it’s still held together by tendons. Then it’s a skeleton that is still held together by tendons, but without flesh and not anymore smeared with blood. And then it’s just loose bones, scattered in all the directions. And then it’s bones bleached white like a conch shell. And then it’s just a bunch of old bones heaped together, and finally it’s dust. Bone dust.

And remember that this body will become a corpse, inevitably. So don’t rely on it to be happy.

I actually personally feel reasonably at peace knowing that this body will be a corpse. I actually sort of like aging, at least right now. I think it’s sort of miraculous that my beard is a little bit grayer every month. I like the aches and pains, the way that the shape of my face is changing, it feels as miraculous as the first snow—evidence that seasons still change. This natural phenomenon is going, and that feels amazing, especially when it’s happening to me.

I think that the fundamental disappointment of our lives is not that our bodies are temporary, but rather that the stories we tell about who we are are temporary. We want to construct a story that proves we are who we think we are. Then it turns out to be false, and it fails us.

It’s especially true of the stories that we tell about our Zen practice. Maybe on some long retreat you had some experience that was really intense. Or maybe you spent some period with your mind in a state that was peaceful and joyous. Maybe you stopped worrying. Or maybe you stopped thinking for awhile, once. It was exciting and you thought, I’m going to always be like this. Or, I’ve had a breakthrough or an insight that’s going to make it possible for me to always return to this state. Then you return to your regular life and you go back to your old habits once again. All of the same anxieties and thought patterns resume. It’s incredibly frustrating.

I think among all of the achievements that I’ve had to forget about and abandon, the Zen achievements are some of the shortest-lived of all. Even the sort of negative achievements: I once did a retreat where I was so anxious about my life that it felt like my whole torso was going to burn up, and I thought, well, at least something is happening. I’m not daydreaming. I am burning up with anxiety. This is a breakthrough. From now on, my meditation is going to be this intense. And it wasn’t.

We try against all odds to hold onto that story, that this Zen experience defines who we are, that we’re making progress. But just the same way that this body will become a corpse and dissolve into dust, it’s the same with all of our Zen experiences. It’s gone and it leaves behind a story that we tell ourselves. And the story becomes a memory. Then the memory becomes a ghost, and it packs up its white sheet and it’s gone.

What if we approach our Zen practice without telling any story about it at all?

All we would do would be to surrender to the experience at this moment, without analyzing it, without relating it to before or after, without relating it to myself. And then this moment. And then this one. I think it would be like stepping out into thin air. It would be dizzying. It wouldn’t be hard, but it would be terrifying.

Zen teachers have used the phrase that it’s like stepping off the top of a hundred-foot pole.

In the Mumonkan, master Sekiso said:

“From the top of a one hundred-foot pole, how do you step forward?”

And then master Chosa says it a little bit differently:

“Someone sitting at the top of a one hundred-foot pole, even if she has attained ‘it,’ has not yet been truly enlightened. She must step forward from the top of the one hundred-foot pole and manifest her body in the ten directions.”

Whatever nice Zen experience you’ve had recently; it’s sad but you have to let it go. Because telling a story about it isn’t going to preserve it. It’ll make a story, but it won’t preserve “it”. You have to keep jumping out into this thin air, over and over again.

It’s not difficult to do this. I think there’s kind of a misperception about the work of dissolving the ego that’s come about because of some of the metaphors we use. Buddha called the ego a house with a strong ridgepole. And when he had his great enlightenment experience he said the ridgepole had been broken. “House builder, you will build the house no more.” Trungpa Rinpoche described the ego as a prison with a locked door. I was describing it just now as a brick wall.

But the self is not solid at all. It’s like a tissue, it’s so weightless, it’s so delicate. It flits around. When you’re doing the dishes, the self flits into the tips of your fingers and the soap and the dish so you don’t drop it. You’re not thinking, I’m rich or I’m poor, or I’m a Democrat or a Republican, or this is how my childhood affected me, or this is what I’ve achieved in the past, right?

This sense that the ego is some structure that you have to take apart, can’t be so, because it’s gone the second that you do anything with your full attention. It only comes back when you start building it again.

Whenever you’re doing what you’re an expert in, the self flicks into the shape that it needs to be and the place that it needs to be for that activity to happen. When we chant, we are mouths and lungs. We aren’t thinking about our pinkies. We aren’t calling ourselves names. I don’t say “I am Jiryu and I am chanting.” It’s just [chanting] Sentient beings are numberless.

Any skillful activity at all is the activity of the self inhabiting the place and the thing that it needs to inhabit. So try to notice that. When we chant in a few minutes, you’re going to defeat yourself, because the second you think about it, you can’t do it. But try to see as you move around in your life, the way that the self changes shape. How weightless it is. How flexible it is. And how, when we want to act smoothly and skillfully without a lot of effort, we use the self as a tool. We send it. Send it into my feet when I’m running. Or I send it into another person when I am practicing empathy. This happens all the time for all of us. It’s not some special Zen thing.

There’s a story about a teacher named Zuigan. Every morning Zuigan got up and he called to himself: “Master!” And then he answered himself: “Yes, yes.”

Mumon commented on this thing that Zuigan did. Mumon said,

“He is opening a puppet show. He uses one mask to call ‘Master’ and another that answers the master.”

And the self is just like this. It’s weightless, it’s elastic, it shifts, it moves.

So here’s the riddle. Who opens that puppet show? Who puts on one mask and then the other? Keishin sitting there is the wearing of the mask. Who’s wearing it? Who’s sitting there?

Mumon says,

Some Zen students do not realize the true person in a mask

Because they just see the ego.

Ego is the seed of birth and death,

And foolish people call it the true person.

The true person who’s the one wearing all the masks, who’s working all the puppets, the one who’s everywhere. That’s who we are, and I think that watching the way that the self shifts and moves allows us to see the unchanging field in which these actions are happening.

That brings us back to that hundred-foot pole. You climbed to the top of it, you accomplished that goal. What’s that really worth to the one who wears the masks?

That yellow 5.9 climbing route that I once mastered, it’s gone. How could I possibly hold on to that achievement? And if once upon a time I learned how to put my foot on a tiny thimble 25 feet up and not be afraid, what’s that worth now? It’s gone.

Master Chosa said,

“Someone sitting at the top of a 100 foot pole, even if she has attained “it”, has not yet been truly enlightened. She must step forward from the top of the 100-foot pole and manifest her whole body in the ten directions.”

Manifesting in the ten directions—that is being the one who wears the masks, the one who is in all the places. As the self flits from shape to shape, activity to activity, the true self is the one who is always in all of those places, all of those shapes.

And it sounds really lofty and special, but it isn’t. It’s truly ordinary life. It’s the life that’s left over when we stop telling a story about the life that we think that we’re living. It’s the life that we have when, with our full attention, we just really wash the dishes, with our self just in our fingers. Or when we really chant with our self just in our mouths and lungs.

Mumon said,

“If you can really step forward from the 100-foot pole and turn back, that is, if you can return to your everyday life and live as an ordinary person, then every movement of your hand and foot will create a new breeze. No matter what you may do, you cannot help but develop your working of the Truth.”

Images: