Is an Enlightened Person Afraid of Illness and Death?

This is a dharma talk I gave at the Village Zendo December 12, 2024, about my mother’s brain surgery and end-of-life decisions. Here’s the video and a transcript.

Two months ago, my mom had emergency brain surgery. She had an artery in her brain that was basically completely blocked. This is the artery that feeds Broca’s area and the temporal lobes. These are the language centers, and language is my mother’s whole life. She’s a scholar of philosophy and law and religion. Reading and writing are her whole career. So this was especially scary for her. She had surgery on a Monday.

Keishin and I went into Mount Sinai and it was supposed to be, I don’t know, six to eight hours. It took 10 hours. We were just waiting and waiting and waiting in the big waiting area that they have there. Finally, we found out that she was done and in the next building over. We went and sat with her until she woke up. When she woke up, she couldn’t speak at all, which nobody had warned us about. When she had gone into surgery, she was fine. She’d had a few episodes of difficulty speaking, but she was totally fine. And then after the surgery, she woke up, and as she was coming out of the anesthesia, she looked over at me. We made eye contact. It seemed like she recognized me. She smiled at me, and then she said “dub dub dub dub dah,” as if she expected me to understand.

And then maybe she seemed scared. There were some tears coming out of her eyes, and she was—she was in the bed spasming. Grabbing the edges of the bed and shaking it, and her legs were kicking. I had no idea what was going on with her, and I was so scared. I said, “Can you point to some part of you that’s not comfortable,” and she couldn’t seem to understand what I was saying. She would look at me and she would nod, but then she wouldn’t comprehend. Or she couldn’t express anything.

She had this huge bandage around her head, and she kept reaching up to scratch behind the bandage, and pull at the bandage. And I kept grabbing her hand and putting it down and saying, “It’s okay, just be patient. Leave that bandage alone. I don’t know why you can’t talk. I think it’s probably just the anesthesia. You’ll probably be able to talk soon. Just relax. Just be patient. Just keep waiting, Mom. I think you’re going to be okay, leave the bandage alone.” We did this for hours. At some point, she finally evaded me and pulled her bandage off, and it was heavy with blood. It was just soaked with blood, and her pillow was soaked with blood.

Whenever this experience got too much for me, I would still be sitting there holding her hand, but I would close my eyes, breathe into my stomach and just be there. I wasn’t reassuring myself because I didn’t know anything. I was just breathing. I was aware of Keishin sitting in the room across from me and watching me, watching my mother. Knowing that was reassuring.

Every once in a while, a doctor would come in and get in Mom’s face and loudly ask, “Do you know where you are?” She’d say “buh.” The doctor would say, “What year is it? Is it 2022? Is it 2024?” She would just look at them. One guy strolled out of the room and whispered to a nurse, “Word salad.”

I asked, “So it’s normal? How long is this going to last? She didn’t have aphasia before the surgery.” And the doctors said either it’s normal, or we don’t know, or wait until you can see some other doctor in the morning.

And finally, it was nine o’clock and we had to go home.

Over the next few days, I did find out, okay, maybe this is at the bad end of a normal spectrum. It doesn’t mean that she’ll never speak again. We still don’t know.

She’d had surgery on a Monday, and Thursday was really one of the worst days of my life. I got a call around nine-thirty in the morning from the attending physician, saying, “Your mother has taken a turn for the worse. She may have had another stroke.” So jumped on my bike and I rode over. I was staying in New York. I rode to the hospital again. Jennifer was upstate. I got her on the phone, and we talked to the doctor.

What happened? “Not sure, but what little language ability and responsiveness she had is gone.”

Will she get better? “Don’t know.”

Before my mother’s surgery, she had said to me, “Look, if something goes wrong and I can no longer write anything worth publishing—two tickets to Switzerland.” Meaning we were going to go to Switzerland together for assisted suicide. This was on my mind the whole time. When I saw her, I would say, thinking she might understand: “Mom, I think you’re going to get better, but if not, I remember your wishes. You can trust me. I remember what I promised.”

Thursday morning was the time to put this into effect.

I said, is she going to get better? “We don’t know.”

Okay. Is she on life-supporting treatment? “Not right now.”

Is there a way that we can end her life? “We can stop feeding her.”

Okay, let’s give it a few more days.

And then she started talking, that Sunday morning, seven days after her surgery. I was home in the city, and while I was in the shower, mom called. When I got out, I picked up her voicemail, and she had said, very carefully, “Hi, Jesse, it’s Dena. Could you bring some coffee when you come?”

That was the first full sentence I’d heard from her in almost a week.

So she spent five weeks in the hospital, total. She finally came home. She’s been home for, I guess, about two months now, little less. And continues to improve. She’s walking with a cane, she’s speaking, she’s reading, she’s writing. Definitely still affected by the surgery, but also definitely not the worst that we had feared.

I’m telling you this story, because this is about Zen training. This is about, why are we meditating? How can we use this training? How can we get it in our bodies such that when the shit hits the fan, we can put it into practice without thinking about it?

Sometimes the old Zen texts seem to think that there’s no point to meditation. They seem to make fun of people who think that there is a purpose to meditation. Every once in a while, there will be a story about some monk who thinks that meditation makes your mind like a perfect mirror that reflects reality with no judgment, with no opinion. And this seems great. It both seems like a very effective state of mind to be in for responding to events, and it seems very peaceful. You don’t see a mirror freak out about what it reflects. It just reflects.

Sounds lovely, right? But then you can tell really the Zen attitude is making fun of this desire to become a mirror. So there’s the contest—no actually, first I’m going to talk about this koan from the Eighth Century.

Nangaku went to his student Baso’s hut and asked, “What are you doing these days?”

Baso the student says, “These days I just sit.”

Nangaku the teacher: “What is the purpose of sitting in zazen?”

“The purpose of sitting in zazen is to become a Buddha.”

Nangaku the teacher, he gets a terracotta tile and rubs it on a rock.

“What are you doing, master?”

Nangaku: “Polishing a tile.”

“What is the purpose of polishing a tile?”

“I’m polishing it into a mirror.”

“How can polishing a tile make it into a mirror?”

“How can sitting in zazen turn you into a Buddha?”

And there’s an earlier story about a poetry contest between two students of Hongren. They’re competing to become his Dharma successor. There is the learned aristocratic student Shenxiu, and there’s the working class stiff Huineng.

So the learned aristocrat, he writes:

The body is the tree of enlightenment,

The mind is like a bright mirror’s stand;

Time after time polish it diligently,

So that no dust can collect.

The other student, the working class stiff Huineng writes,

Enlightenment is not a tree,

The bright mirror has no stand;

Originally there is not one thing—

What place could there be for dust?

And he, of course, is considered the winner and our ancestor, right? The one who says there’s no mirror to polish, there’s no dust to remove.

So what’s the point of meditation? Become a flawless mirror that perfectly reflects reality with no smudgy delusion? Or is that idea actually stupid and there is no point to meditation whatsoever. And if so, what were we doing for that last half an hour? And why?

And even taking another step back from this, some texts really seem to criticize asking questions like this, like, “What is the purpose?”

There’s the koan where Jizo asks Hogan, “What’s the point of going on a pilgrimage?” Hogan says, “I don’t know.” Jizo says, “Not knowing is most intimate.”

So should we be asking this at all? Should we be trying to know what is the purpose of meditation, or not?

Now, look, I’m Jewish. I can’t help asking questions like this, analyzing texts, getting myself involved in the arguments. There’s a two-thousand-year-old Jewish joke about this: Somebody who is considering converting to Judaism goes to the Rabbi Shammai and asks: “Explain to me the whole Torah while I stand on one foot.” Shammai is offended and chases the person out.

The same person goes to Rabbi Hillel and asks the same question: “Explain all of Torah to me while I stand on one foot.” Hillel says, “What you would hate if it were done to you, don’t do it to other people. The rest is commentary. Go study it.”

It’s a famous story because it gets both sides: Wisdom is very simple, and it’s very complex. And the complexity is worth studying.

So let’s do this. Let’s boldly analyze what is the point of meditation.

Here’s one answer: We are likely to experience old age and sickness, and we are definitely going to die. And most of us experience some anxiety about this. So maybe the purpose of meditation is to resolve this anxiety. In the old stories about Buddha, yes, for him, resolving this anxiety was the thing that motivated him to meditate. After studying meditation for six or seven years, he had learned yoga and magical powers, and he had almost starved himself to death, he sat under a tree and made the vow that he would not get up again until he had resolved this anxiety about sickness and old age and death.

And his insight after eight days of sitting was that suffering is caused by thirst, by trishna, by the desire for things to be different from how they are. For less of what we don’t want. For more of what we do want. And that is on a foundation of delusion, that the self is this separate and lasting thing that I can guard the borders of. That I can defend from the things that I don’t want. The borders behind which I can accumulate more of the things that I do want. And by seeing that this is all an illusion, we can resolve this anxiety about the end of this.

The monk Dogen had a similar story. He’s the founder of our lineage in Japan. He was born around 1200. When he was two, his father died, and when he was seven, his mother died, leaving him an orphan. At his mother’s funeral, he watched the incense rise up into the air and disappear. And he was devastated. Does this happen to everybody? Does this happen to everything? Will this happen to me? How do I understand this? How do I live with this knowledge? So that was what initially drove him to the monastery.

Now, in the 1700 years between the lifetime of Buddha and of Dogen, a lot had been written down. Dogen read a lot of this stuff—he was a big scholar—and he read all of these paradoxical texts like, “There’s no mirror for dust to settle on.” Or, “Meditating to become like a Buddha is like polishing a tile to make it a mirror. It’s hopeless.” And he thought, okay, there’s something they’re not telling me: Why are we doing this?

He traveled from Japan to China when he was 23, and traveled around China for four years. He found a teacher, Rujing, who seemed to him to have the real-deal original Chinese Buddhism. He studied with Rujing, and had a great insight. And his insight was: practice and enlightenment are the same thing. He wrote:

To suppose that practice and realization are not one is a view of those outside the way; in Buddha Dharma they are one and the same. Because practice within realization occurs at the moment of practice, the practice of beginner’s mind is itself the entire original realization.

When I first heard this slogan, I found it completely uninspiring. “Practice is enlightenment” pissed me off.

At 22 I was miserable. I was depressed. I was smoking pot every day. I was failing at my job. I hated myself. I turned to meditation for help, something that would fix me. I wanted to get enlightened, because I heard that enlightenment was liberation from suffering, and I was suffering. So I checked myself into a monastery for a year. And we chanted Dogen. We read Dogen together. I kept getting this message, “practice is enlightenment.” And I thought, this is a scam. Practice isn’t enlightenment. It’s a grind.

So I ignored this slogan, that practice is enlightenment, for years.

But after about 15 years of meditation, it started to make a little bit of sense. This is just my view of the teaching, but it’s been helpful to me, maybe it’ll be helpful to you: I am no longer trying to become enlightened. I’m trying to be enlightened more of the time.

Like right now, I’m paying attention to you. I’m aware that I’m in this room. I am trying to speak the truth. I’m being enlightened. Then in a little bit I’ll get on the subway. I’ll shove somebody aside, I’ll get lost in thought, I’ll be deluded. And then I’ll come to, and then I’ll be enlightened again. And for sure, after spending so many years of practice, both sitting cross legged and staring at the floor and everyday practice, I am being enlightened more often than I was before.

Now, I’ve read stories about people who become enlightened, and it’s a permanent change in their life. There are thousands of these stories. And I can’t say that I know for sure that this is just a folk tale. But as I get older, as I have more experience—I become more skeptical of these stories. Most of them are hundreds of years old. We don’t know these people, we don’t have a lot of independent witnesses of their behavior. And it’s a little bit suspicious that of all of the modern people who have claimed to be enlightened, almost inevitably they turned out to be alcoholics who sexually abused their students. I think we need to think very carefully about what path we are on. If that is one of the terminal subway stations, we need to figure out which station we transfer at. And I think we also just need to question whether this mindset of achieving some lasting change, as opposed to practicing being enlightened now, what effects those two things have in the long run on who we are and how we treat other people.

So I’m just trying to be enlightened more, and that’s what “practice is enlightenment” means to me. When I’m practicing, I’m being enlightened.

It’s true that being enlightened means not suffering. When I was sitting with my mom, when she came out of surgery, or when I was talking to the doctor about maybe ending her life—those were some of the most challenging moments in my life. But I wasn’t suffering. I wasn’t wishing it was different. I wasn’t thinking, “poor me.” I wasn’t thirsting for something else, because I was in the moment. I was very aware that I was being called to respond and that I needed to bring my whole self to it. And therefore I wasn’t suffering at all, because I wasn’t thinking about, “Do I prefer this or not?” I was just responding.

So Mom’s recovering slowly, as I said. This Thanksgiving, she actually was able to come up to New Paltz and have Thanksgiving dinner with Keishin and me—which, you know, was dicey. I wasn’t sure, but it worked out fine.

After Thanksgiving dinner, I saw her standing at my kitchen counter, and she was picking up one foot and putting it down, picking up one foot and putting it down. She said, “I bet you can do this for a whole minute, right?”

I said, do what?

She said, “Stand on one foot for a minute.”

I said yep.

She said, “It’s a physical therapy thing. I can only do it for a few seconds.”

And I said, well, I better summarize the Torah real quick then.

She laughed! She got it immediately. She said, “Very clever. Very well done.”

And I was aware, and I am aware, that my mother is just about the only person I know who would get that joke, who I can make that joke to. I didn’t know if she was gone or not, and she’s back. I have her, for now. Not forever, but for now. And that’s what being enlightened means for me, is to appreciate that.

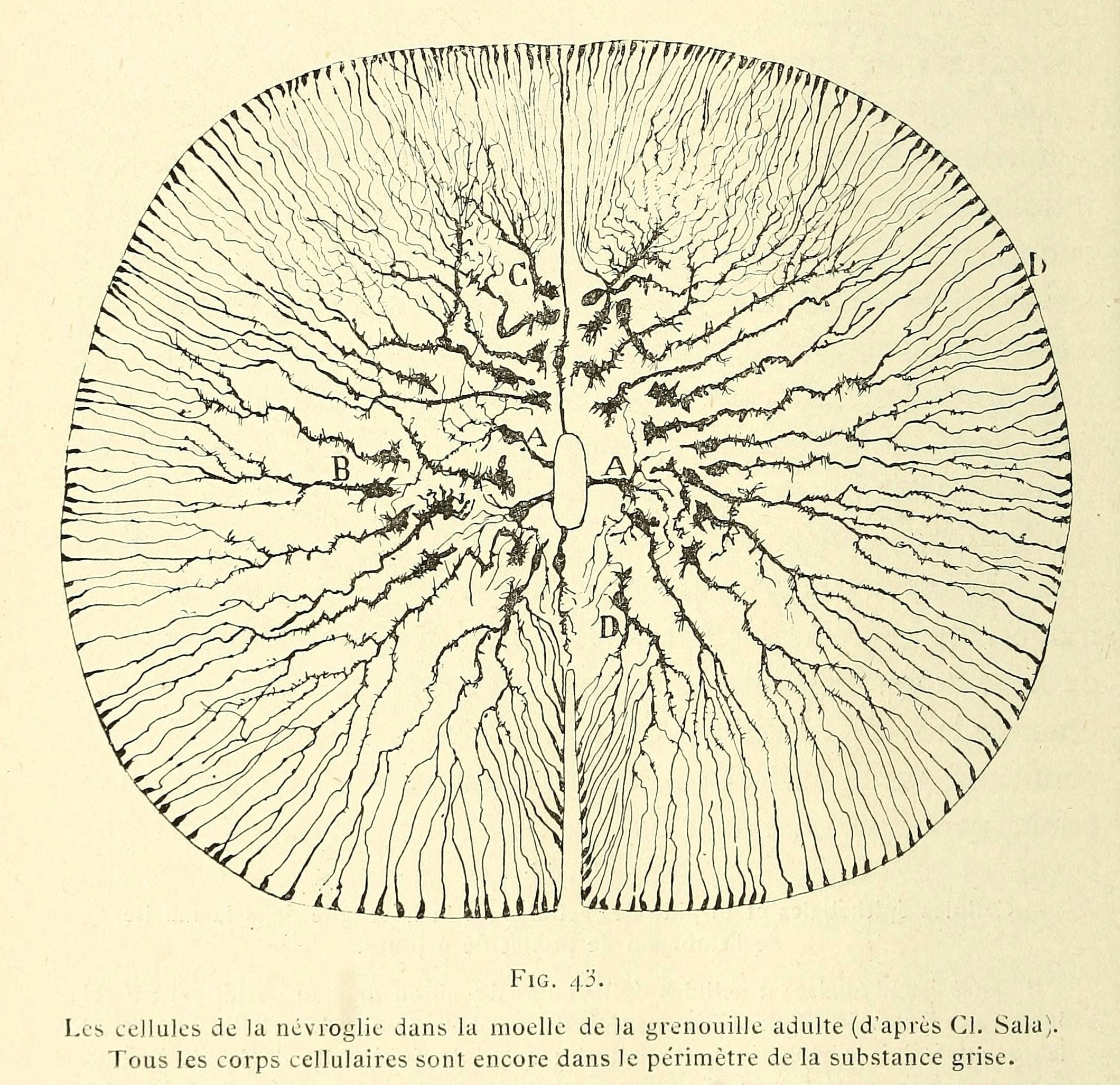

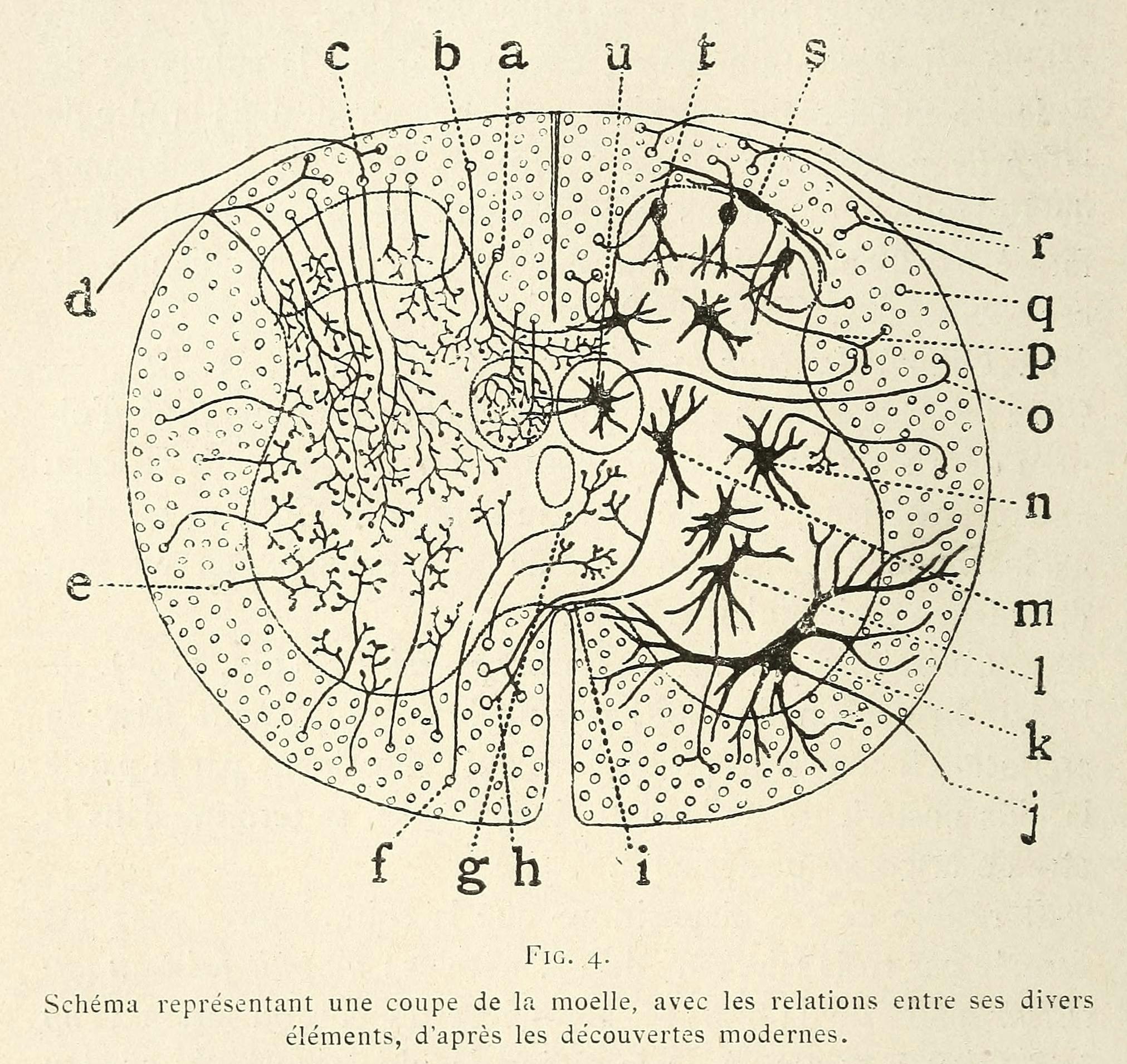

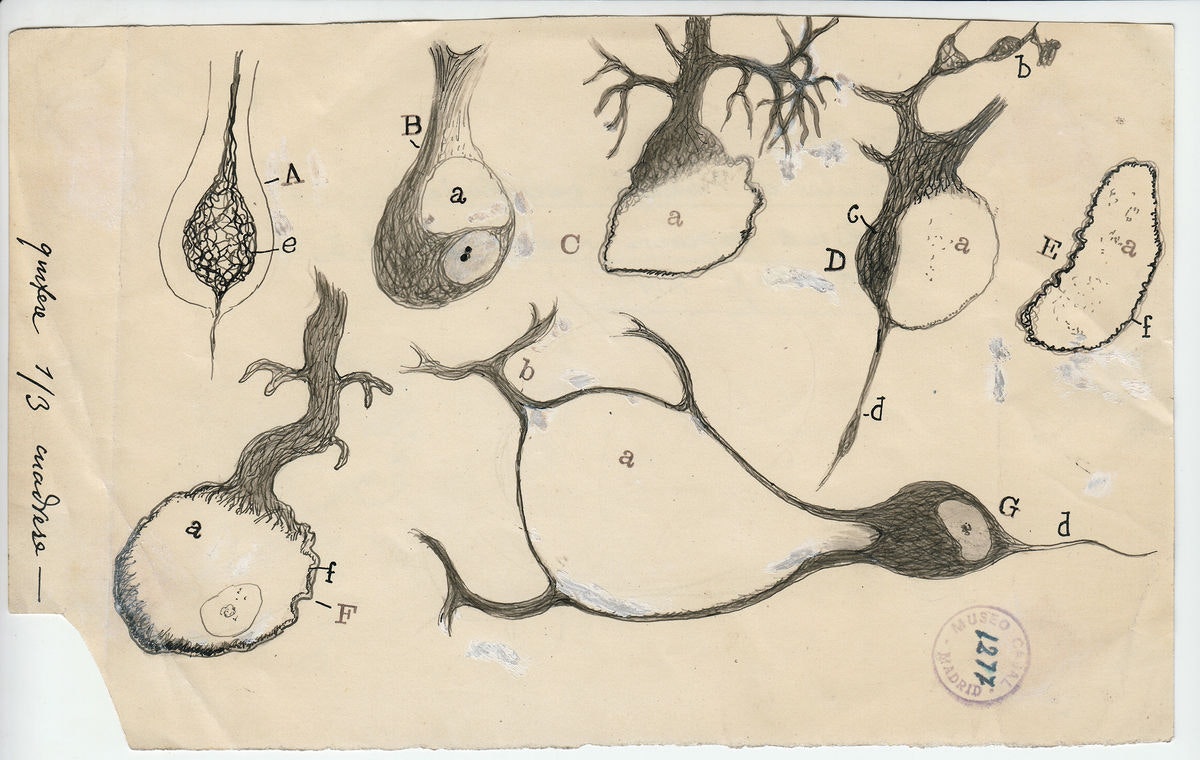

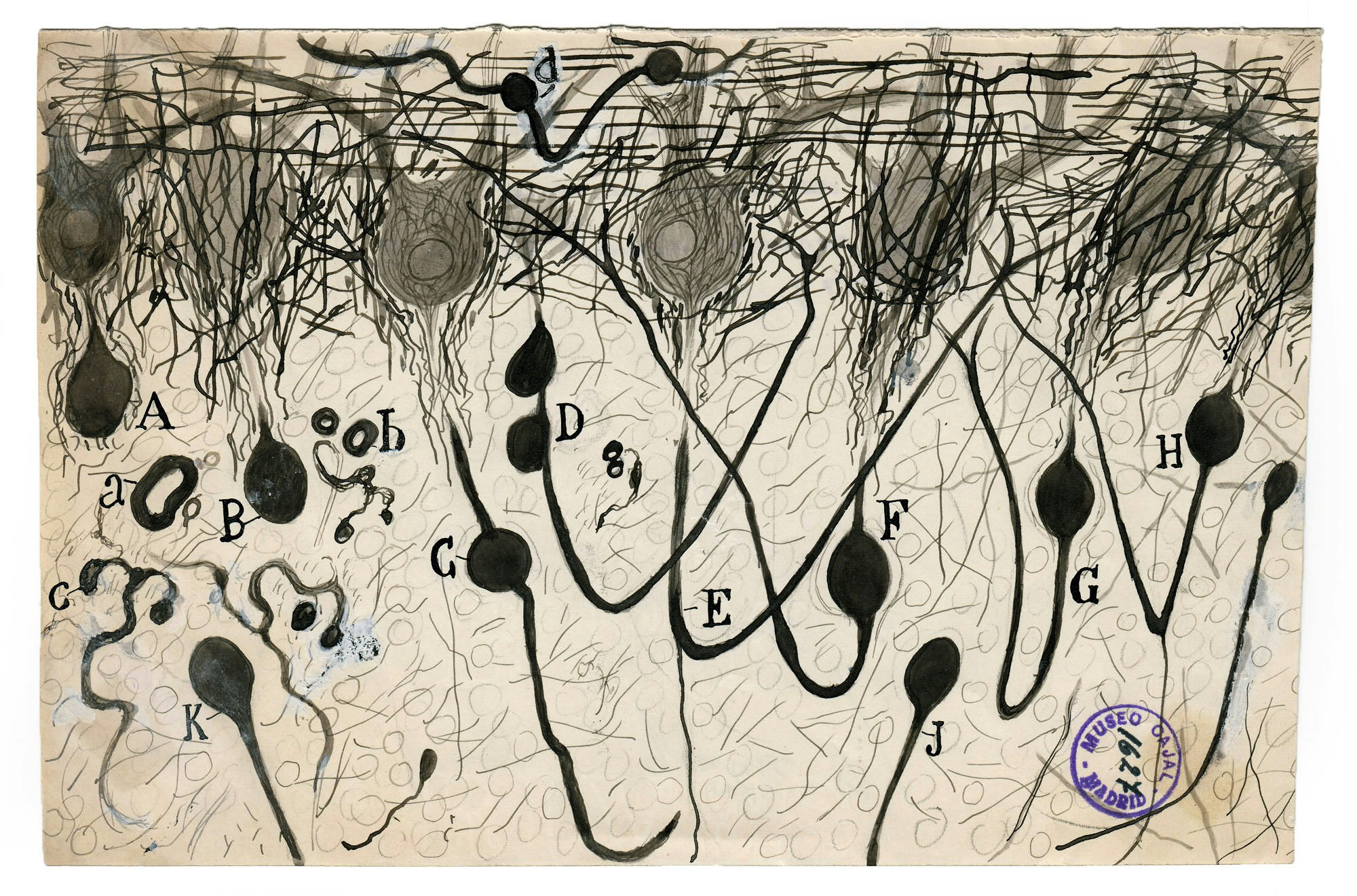

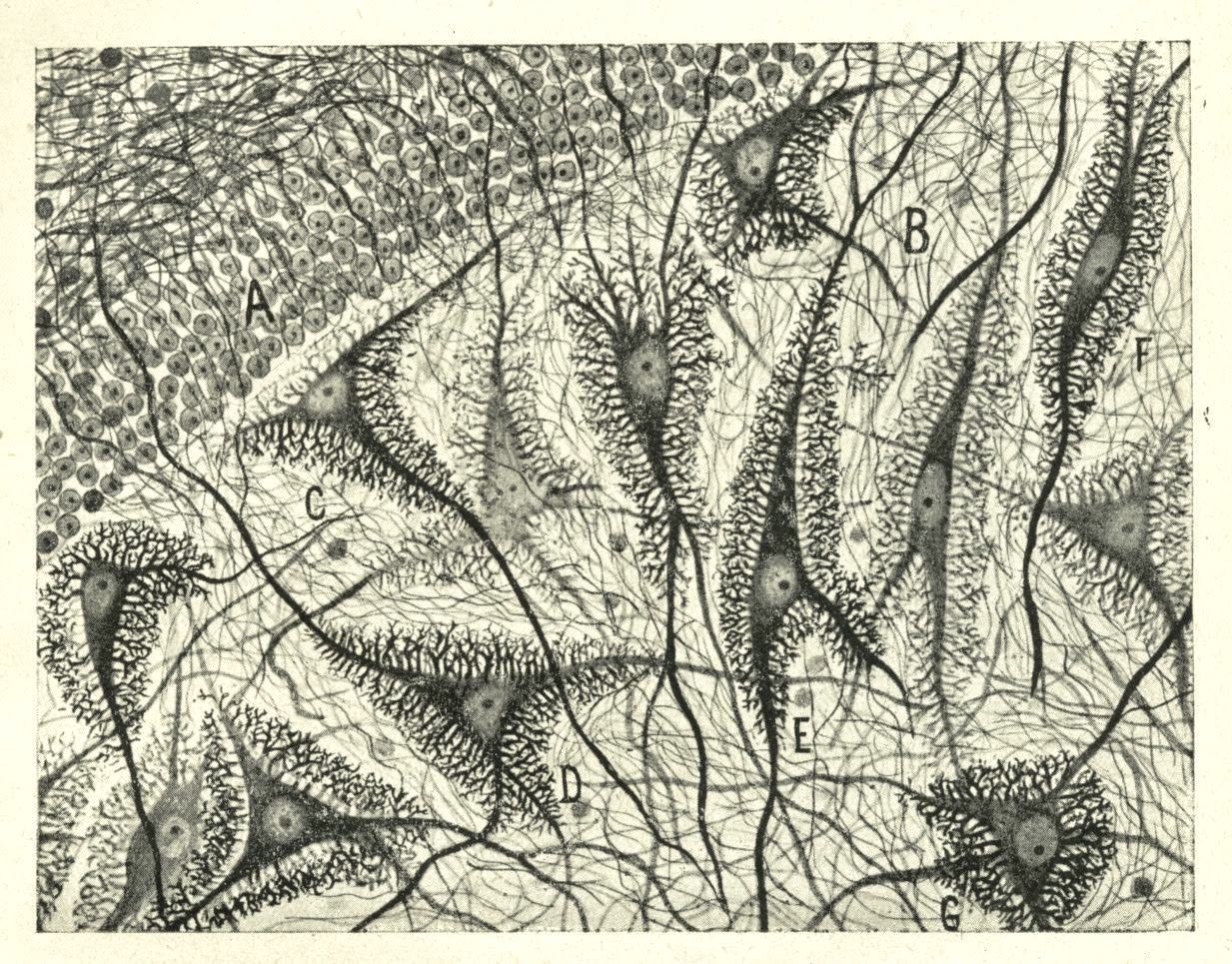

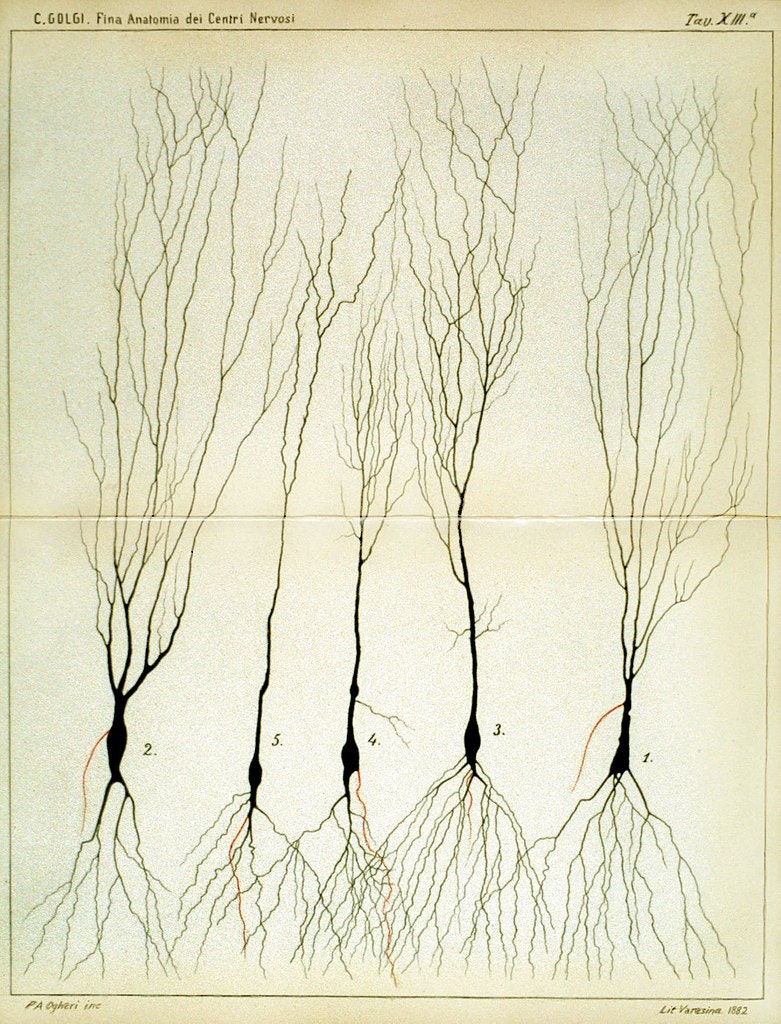

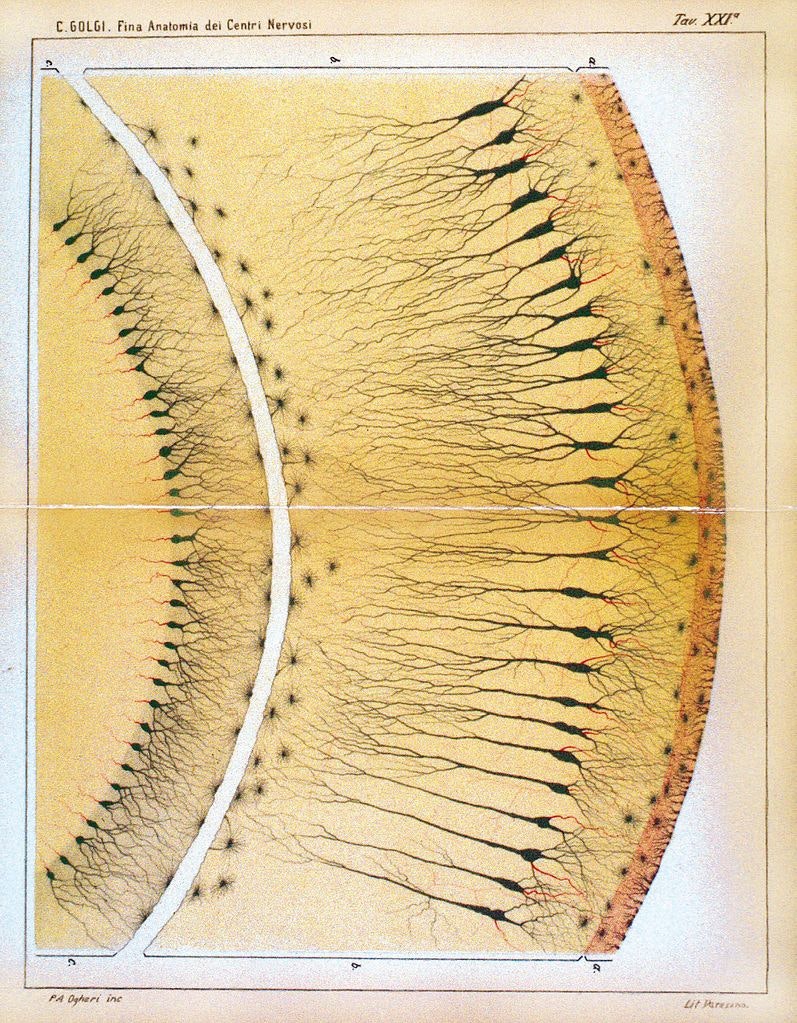

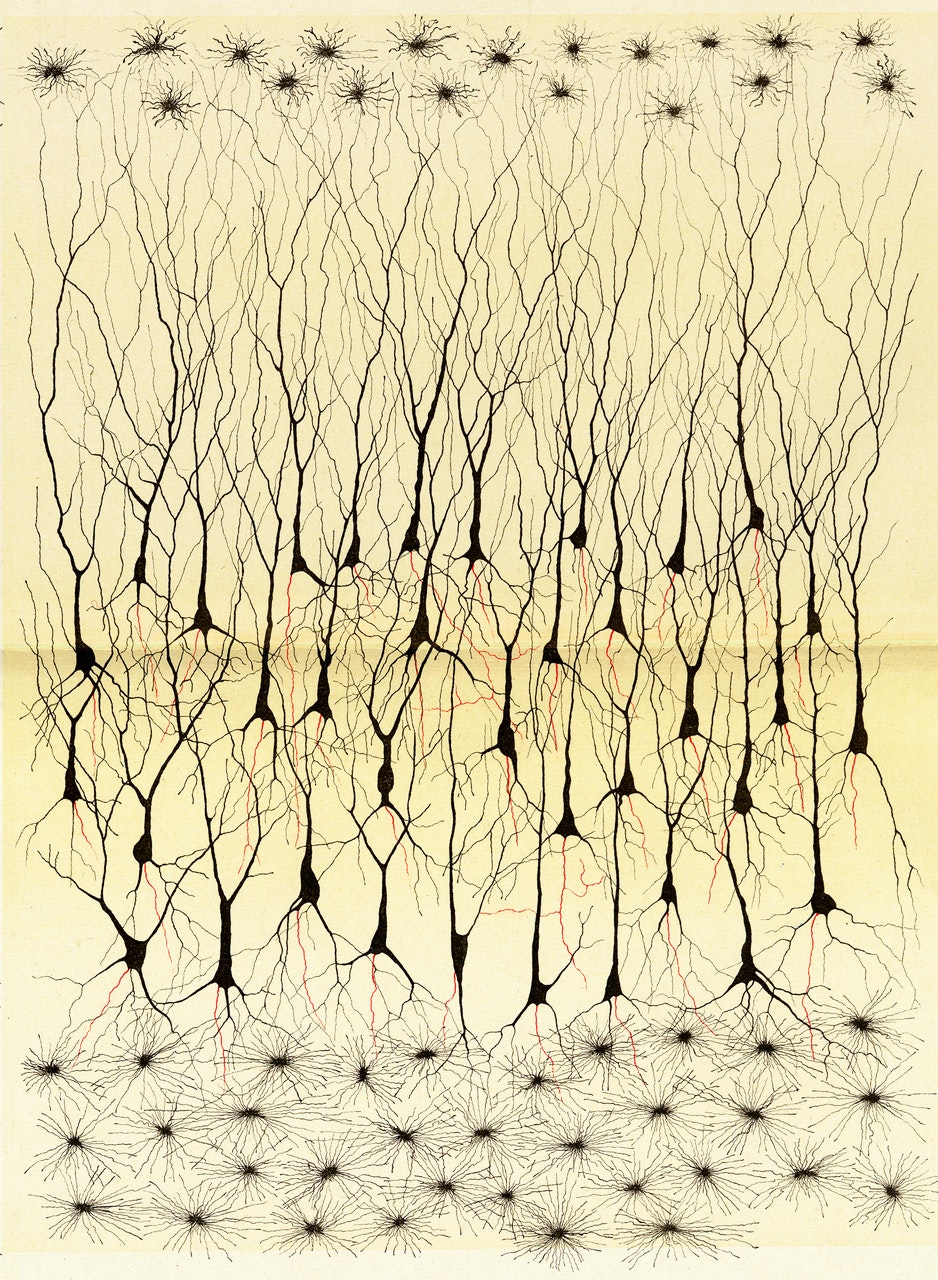

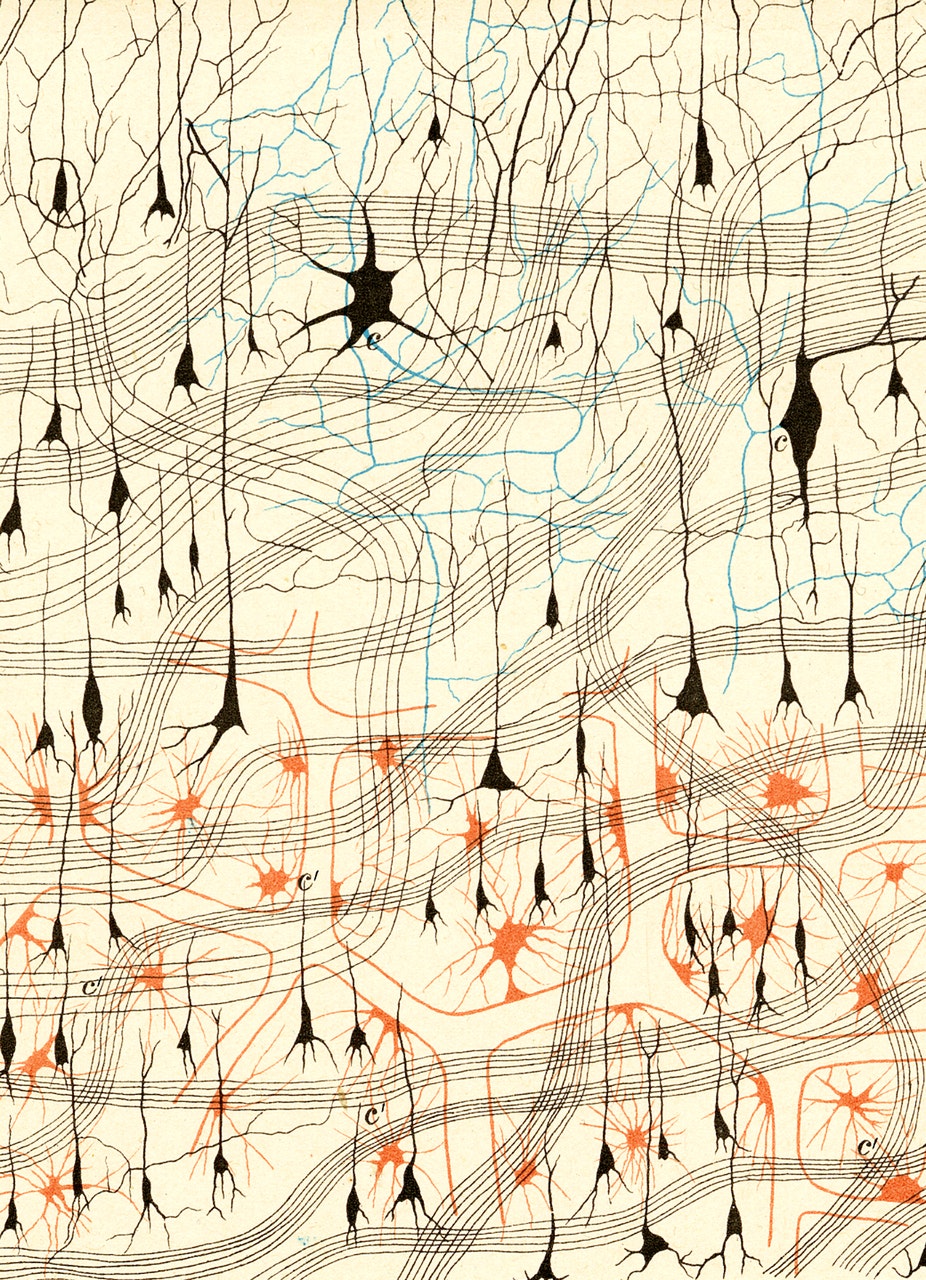

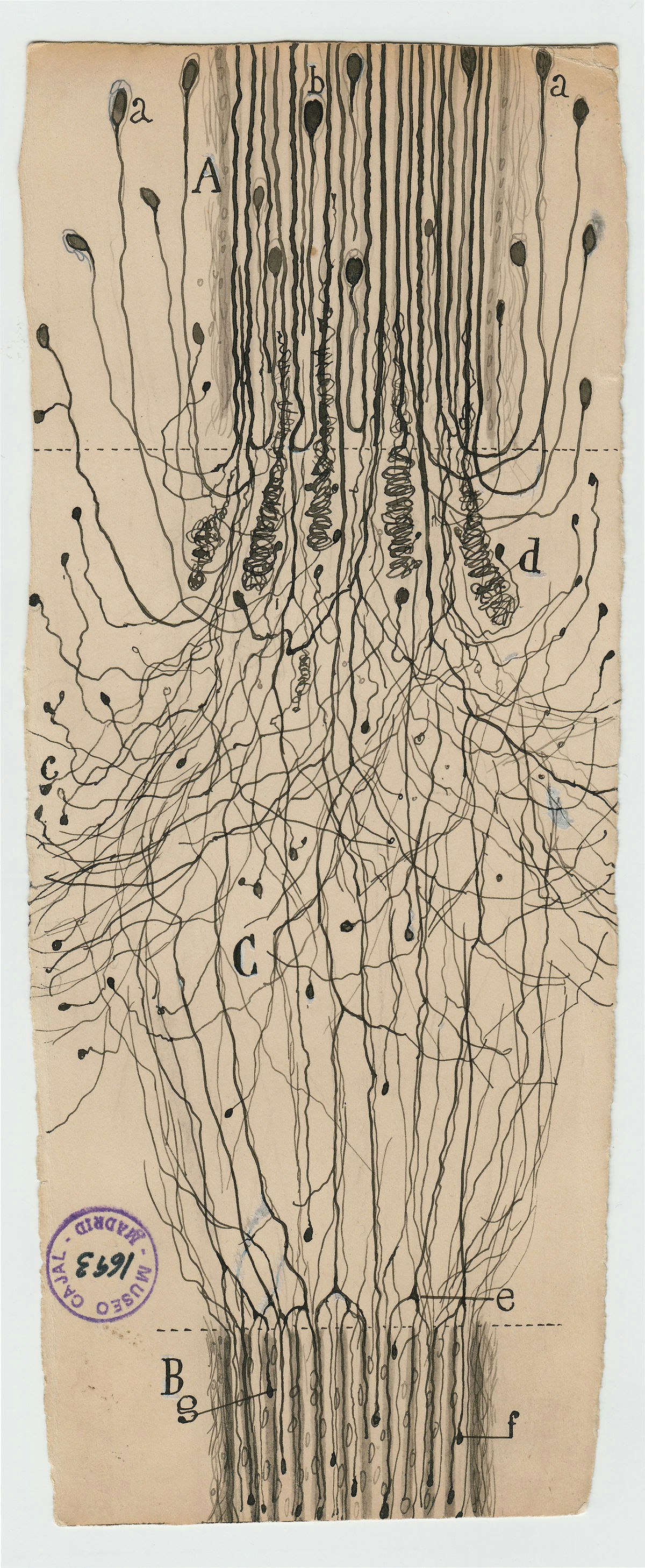

Images: Early Illustrations of the Nervous System by Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal.