Video From PloneConf 2017: Why Generosity Turns to Rage

I talked in Barcelona in October about being nice to newcomers who ask basic questions. We go to StackOverflow and mailing lists and forums with the intention to be generous, so why do we nevertheless act cruelly to beginners? Why do we lose our tempers? And what can we do about it?

My talk got a rocky start. I didn’t realize how hard it is to get a cab in Barcelona on a rainy morning, so I arrived late. My A/V didn’t work for the first few minutes. Nevertheless it was a joy to give this talk; the Python and Plone community in Barcelona was very gracious to me.

Transcript #

I’m a Python and C programmer from New York. I work for MongoDB there. I want to talk today about generosity and why generosity so often goes wrong. We try to help newcomers, and we start off with this intention to be generous to them and to help them out. Then we lose our temper and we get mad at them and we become cruel. I think I understand why this happens and I think that I also have a method for how to prevent this from happening to us. That’s what I’m going to talk to you about today.

Angry Santa Claus #

In the United States, the symbol of generosity for us is this character named Santa Claus. You might know him as Saint Nicholas or Father Christmas. He goes around giving presents to children on the night before Christmas, distributing gifts for free. In recent years in New York City, we have a new tradition which is called SantaCon. SantaCon is when a bunch of young men, mostly, come to New York City and they dress up like Santa Claus and go around having a big party. A few years ago, I was walking around New York City and I saw the most amazing thing. A young man who was dressed like Santa Claus with the white hat, fake beard and red jacket, was talking to a homeless man who was sitting in a wheelchair on the sidewalk. The homeless man asked Santa Claus, ‘Can you spare some money?’ And Santa Claus digs into his pocket and he comes out with a five dollar bill. It’s a substantial amount of money. He thinks for a second and then gives the five dollar bill to the homeless man in the wheelchair. And the man in the wheelchair, he just takes the money and puts it in his pocket. He doesn’t say, ‘Thank you.’ I don’t know why; he’s tired or something. And all of a sudden, something goes wrong. Santa Claus becomes enraged at the homeless person. He says, ‘Dammit. I gave you five dollars. I meant to give you one dollar. I would have given you a dollar but five is the smallest I had, so you should feel lucky. This is your lucky day. You should at least say thank you.’

This is terrible, right? It’s terrible for a couple of reasons. First of all, it’s terrible because of power. Santa Claus is a privileged, young, white man with money and a home. The other man is a middle-aged, black, disabled person without a home. And Santa Claus is just yelling at him. It’s terrible. The other terrible thing is that Santa Claus is dressed like the symbol of generosity. He had intended to be generous and in a moment, something went wrong and he became cruel and angry.

So, why does this happen? This isn’t just a story about Santa Claus, this is a story about technology communities. This happens in technology communities every day. It happened to me a little while ago. I was hanging out on Slack, where new MongoDB employees hang out and ask each other questions. This new colleague of mine got on Slack and said, ‘Hey, how do I do such and such with MongoDB? Does anybody know the answer?’ And I thought I knew the answer. I said, ‘That’s going to be implemented in the next release.’ And then this person asks a follow-up question. ‘What’s the ticket number for that feature?’ And I don’t know why, but suddenly I got furious. I got really sarcastic. I said, ‘I memorize all ticket numbers. It’s 12345.’ And then he asks, ‘Are you sure? I can’t find ticket 12345.’ And yeah, I laughed, too. We all laugh at this. I played a trick on him. But I immediately felt terrible. I’m one of the most senior programmers at MongoDB. This is not the kind of behavior that I want to demonstrate to new employees, that we humiliate people in public because they make us angry.

Why Does It Matter? #

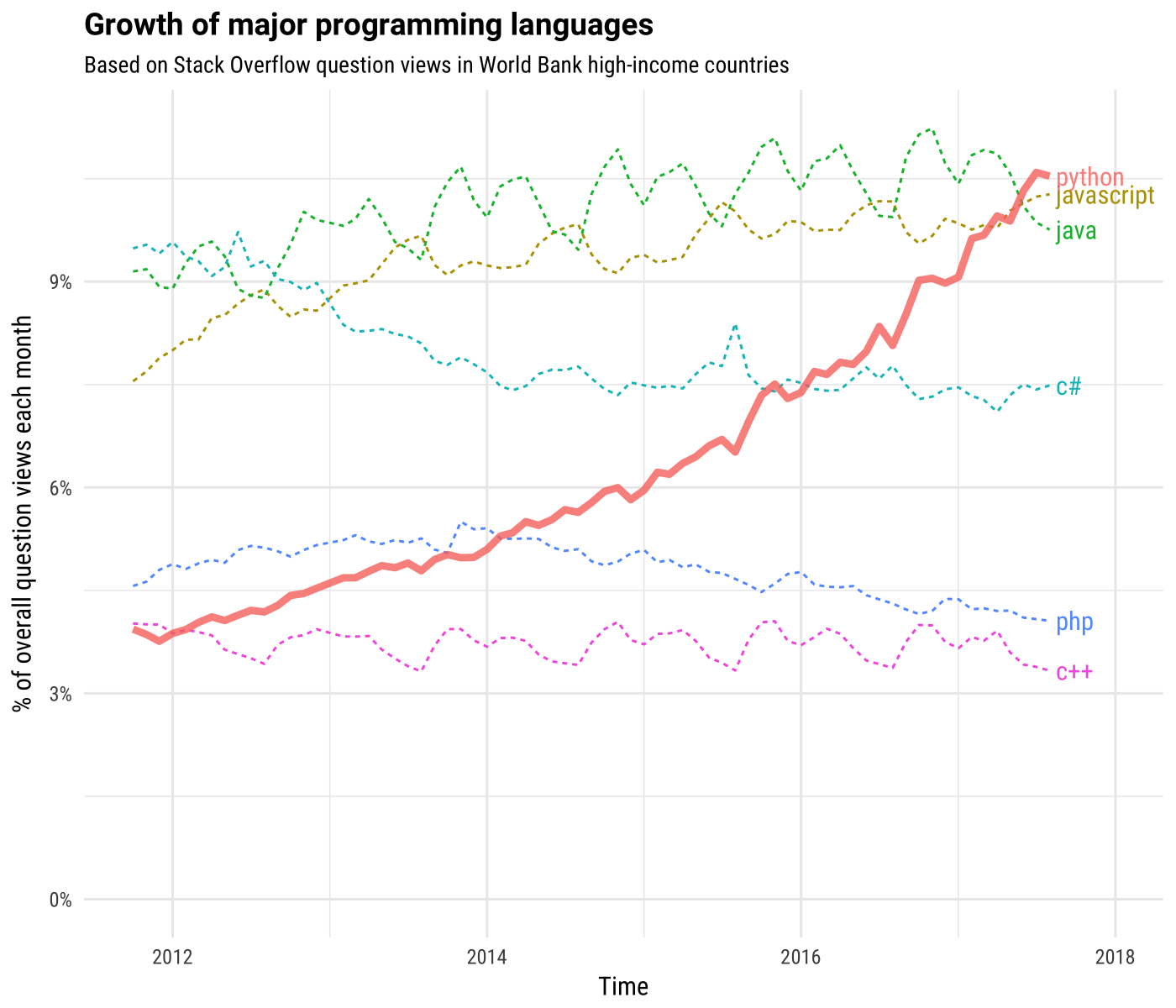

Now you might ask, why does this matter at all? We’re here to write code. If the code works and it’s fast, does it matter if we’re nice to each other or not? I think it does. Last month on the Stack Overflow blog, David Robinson wrote this article that showed that Python has been growing incredibly fast for the last six years. It’s the most popular of the major languages that people ask questions about on Stack Overflow. If you’d asked me a few years ago whether Python was going to be beating JavaScript or Objective C or Swift or Go, I would not have predicted this. The author made a very simple projection that showed over the next two years—even in the most pessimistic forecast—we are going to far outgrow the other languages on Stack Overflow. I think that there’s a couple reasons for this. Python has a great syntax. It’s versatile. We are good at scripting and web application development. You can write a database in Python. And I think that we’re good at data science, which is driving a lot of this recent acceleration. I also think that we’ve got a really strong community and we welcome newcomers. We’re a nice community of programmers. And in particular, I think that we started to understand that developing a community that is inclusive and diverse is important. We understood that before most other language communities did. That also contributes to this growth.

This is good news for everybody in this room because we are all Python experts, or we are becoming Python experts. If you’ve come to this conference you’ve invested in your skills and you’re spending time with this community. So, the fact that Python is becoming more and more popular, it’s good for us. It makes our skills more valuable. You’re going to see that reflected in your salary, in your job opportunities and in your job security. This chart means that our skills are becoming more valuable every year.

But we still have work to do. Our community is not as welcoming as it could be.

The Trouble With Stack Overflow #

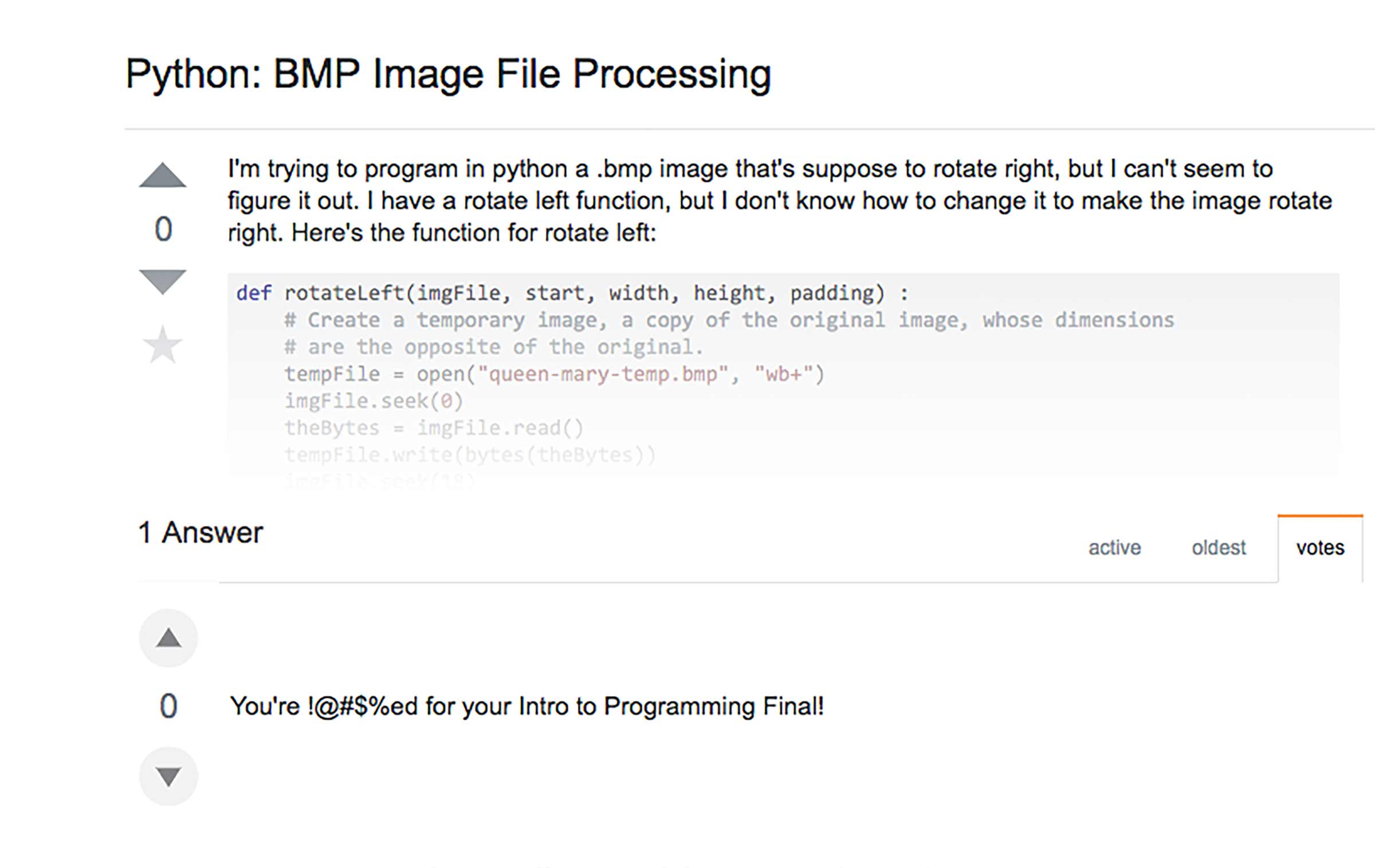

I searched Stack Overflow for rude answers to beginners’ questions and it was not hard to find examples. Here’s somebody asking about image processing in Python. It’s a perfectly reasonable question.

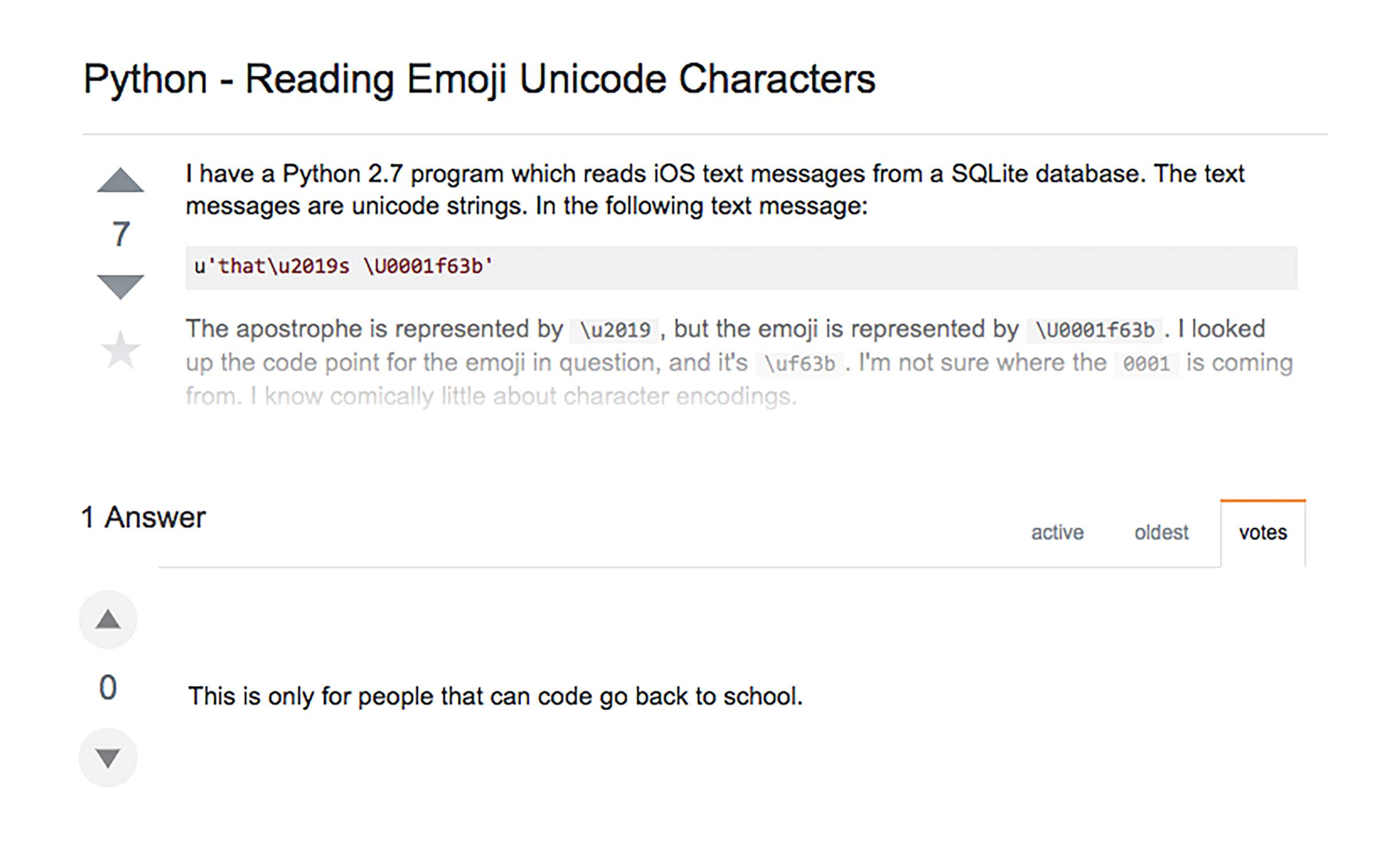

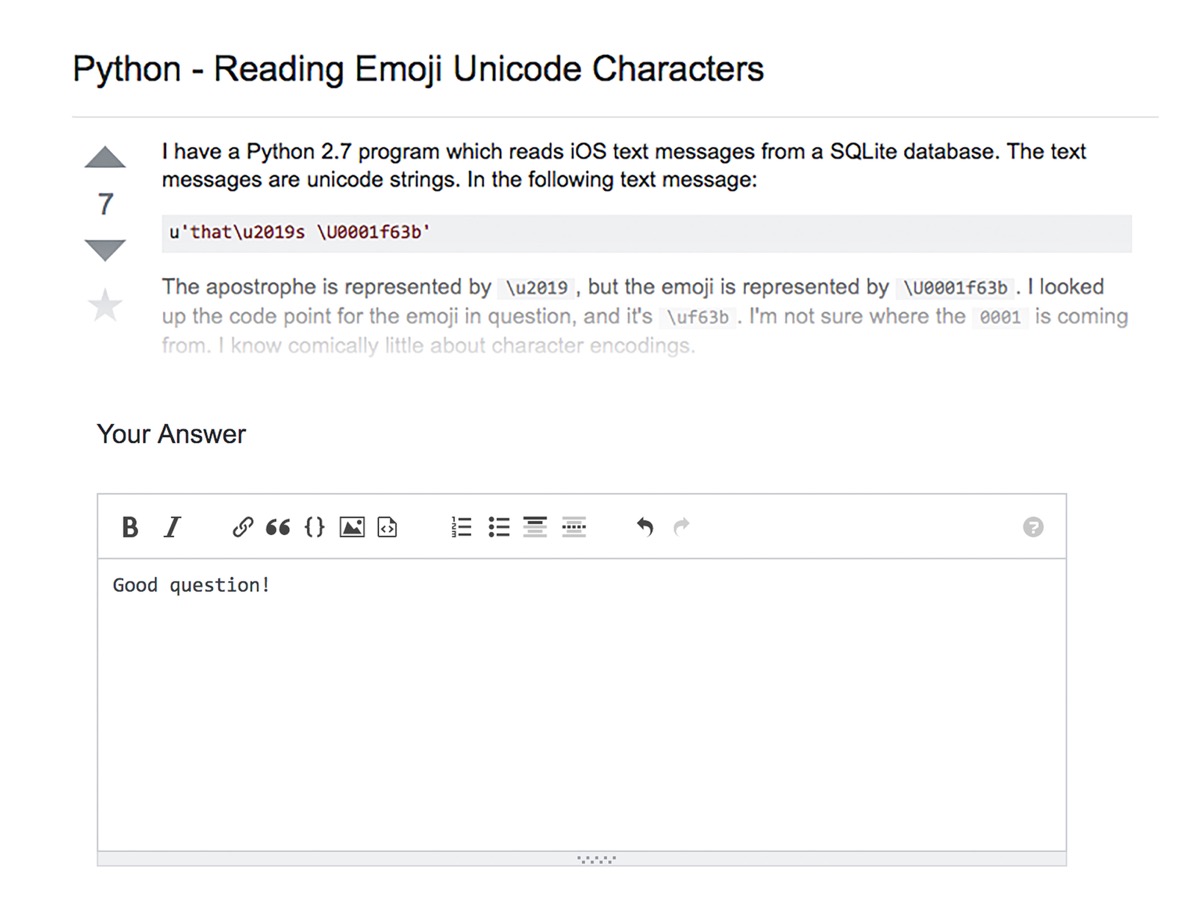

The very first answer to this is, ‘You’re fucked for your intro to programming final.’ What’s the message here? The message is, ‘If you’re asking a question you must be a student and you are doomed. You are not going to pass. You’re not smart enough. Get out.’ I immediately found another example of this bad behavior. Somebody is asking about Unicode in Python.

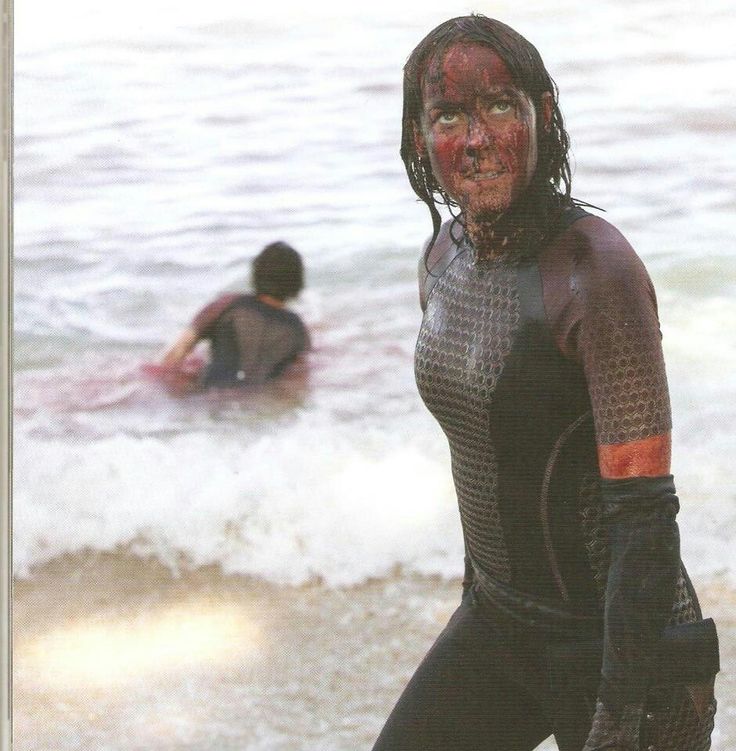

Who here has never been confused by Unicode in Python? And yet, somebody answers with, ‘This is only for people that can code. Go back to school.’ Again, the message is, ‘You are lazy and stupid. You don’t belong here. Get out.’ And part of the problem here is Stack Overflow. Stack Overflow really is a nice place to visit if you’re not asking a question. You can read other people’s’ questions and answers and it’s great for that. It’s sort of like Hunger Games. Hunger Games is a sci-fi movie, it’s in English, maybe you’ve seen it. It’s about children who kill each other. And Stack Overflow is kind of like that because if you ask a question, all of these strangers start fighting each other to get those 15 points to be the one whose answer is marked correct. The outcome is very pretty, right? The winner of the contest has this lovely dress.

It’s great to watch, it’s lovely to be in the audience, but if you’re asking a question on Stack Overflow, I think it’s a little bit more like this.

You’re covered in blood and there’s bodies in the surf behind you. I’m not here to describe what should change about Stack Overflow to make it a community worth joining. But I do know what you and I can be better participants in Stack Overflow. We can control our own behavior.

I’d like to do a little interactive exercise. I promise it will be short, though I won’t promise it isn’t painful. I’d like you, first of all, to pair up. Turn to your right or your left and introduce yourself. Now, you’re going to do the exercise. The person on the left, please repeat after me. ‘How do I convert from PNG to GIF in Python?’ Person on the right, you say, ‘Just Google it. You’re lazy and stupid.’

How does this feel? And what does this do to our community when we treat each other this way? It decimates the community. We drive people away when we treat each other this way. Some of our best experts leave everyday because they see us treating each other this way. Maybe they’re still programming Python, but they’re not participating in conversations anymore online.

The other thing this does is it drives away newcomers. I think that particularly, if you’re not confident that you belong with us, when somebody treats you this way it can drive you away. So, we’re losing out on some of the best minds of the next generation. People who could be the great Python programmers five or ten years from now. They ask a beginner question and somebody is mean to them and they’re gone.

And finally, it feels bad. What did it feel like to say, ‘You’re lazy and stupid’? What did it feel like to be told, ‘You’re lazy and stupid’? That’s not the kind of community I want to be a member of.

This is not in our interest, it hurts our community, it makes our skills less valuable because we drive people out. So, why do we do this? Why do we act against our own self interests?

Why Generosity Turns to Rage #

I think that there are three scenarios that I find make me really angry and make me treat people badly. One of them is when I act generously and I don’t get the reward I was expecting. This happened to Bad Santa, right? He gave a five dollar bill to a homeless man and he didn’t get the thank you and the good feeling he was expecting and so, he got angry.

The other thing that can happen is when you encounter an unexpected difficulty. This can happen on IRC, mailing lists, Stack Overflow. Even face to face. Somebody asks me a question, I make an effort to answer it, and then the person doesn’t understand my answer or I need to explain it more clearly. All of a sudden, it’s harder than I thought it was going to be and I lose my temper.

The final thing that can really make me angry is when I feel like I’m trapped. I must answer this question even though I don’t want to. I heard a story about an example like this. There’s a man named Sawyer X who is a prominent Perl programmer. Sawyer was giving a talk at a conference. It was a Perl conference, he’s a Perl programmer. He gave a talk about Perl web frameworks. It was very well thought out and sophisticated. Sawyer gave the clearest explanation he could. And then it was time for question and answer. So, somebody gets up from the audience and asks, ‘Hey. I use PHP. Is there any need for a web framework or not?’ And it’s irrelevant. It has nothing to do with Sawyer’s carefully prepared talk, but he can’t just say, ‘I’m not going to answer that question’ because he feels like he’s in the arena. You can’t just say, ‘I’m not going to answer that’ when you’re in a room with lots of people. So, he made fun of the guy. He said, ‘If you use PHP, I can’t help you.’ And the audience laughed and Sawyer felt clever. But he told me he immediately regretted that he had done this. And he vowed never to lash out as somebody like this again.

So, these are three scenarios. Unexpected difficulty, sense of obligation, feeling trapped. They all kind of boil down to one thing which is, we have expectations for how things are going to go. That we’re going to make a certain amount of effort and get a certain reward. When those expectations are violated, we get angry.

I’ve been practicing Buddhism for many years and my thinking about this is influenced by Buddhism. Buddha talked about this in his very first tech talk. Buddha was at a small conference. They didn’t even have a venue, they were just sitting under a tree. And Buddha had just had his great insight after many years of meditation. He explained what he had learned in terms of four truths, The first truth is that to be alive is to be dissatisfied, to want things to be better than they are now. We don’t accept the way things are. This dissatisfaction is caused by wanting more of what we want and less of what we don’t want. And expecting that if we get more or if we get rid of more, that it will make us happy for a long time. This is the unrealistic expectation. If I get a promotion or if I delete ten emails, that’s temporarily satisfying but it doesn’t make me happy for the long term. We suffer because we expect that it will make us happy and that’s not realistic.

The third truth is that we can stop being dissatisfied. We can liberate ourselves from this feeling by understanding our own minds, by understanding that our expectations are not realistic.

The fourth truth is that the way to transform ourselves this way is to live a generous and ethical life and to understand how our minds work. I’ve been studying this stuff for many years, I’ve been meditating for many years, it doesn’t mean that I don’t get angry all the time. Just a week ago, somebody commented on my video on YouTube. I uploaded this video called, “How do Python Coroutines Work?” This took me months of research and preparation and rehearsal to create this video. Then somebody posts a comment, ‘I want to master Python. What should I do?’

This just really pissed me off. I wanted to say something sarcastic like, ‘For starters, maybe you could spell Python with a capital P and end a question with a question mark. And just Google it. You’re lazy and stupid. I don’t have time for this.’ But I didn’t. It’s easy enough to close a tab, it’s just command + W on a Mac and it goes away. I was just too angry to answer this person, so I just didn’t answer at all. And that works fine.

What To Do About It #

This is the beginning of my method for how not to be angry at people and how not to treat them badly. This is the second half of this talk. This is what to do about this rage that we sometimes feel. I want to start with a little aside. This talk is not for trolls. I know that people join communities with bad intentions, but this talk is not for them. The only thing that I know how to do with trolls is ban them.

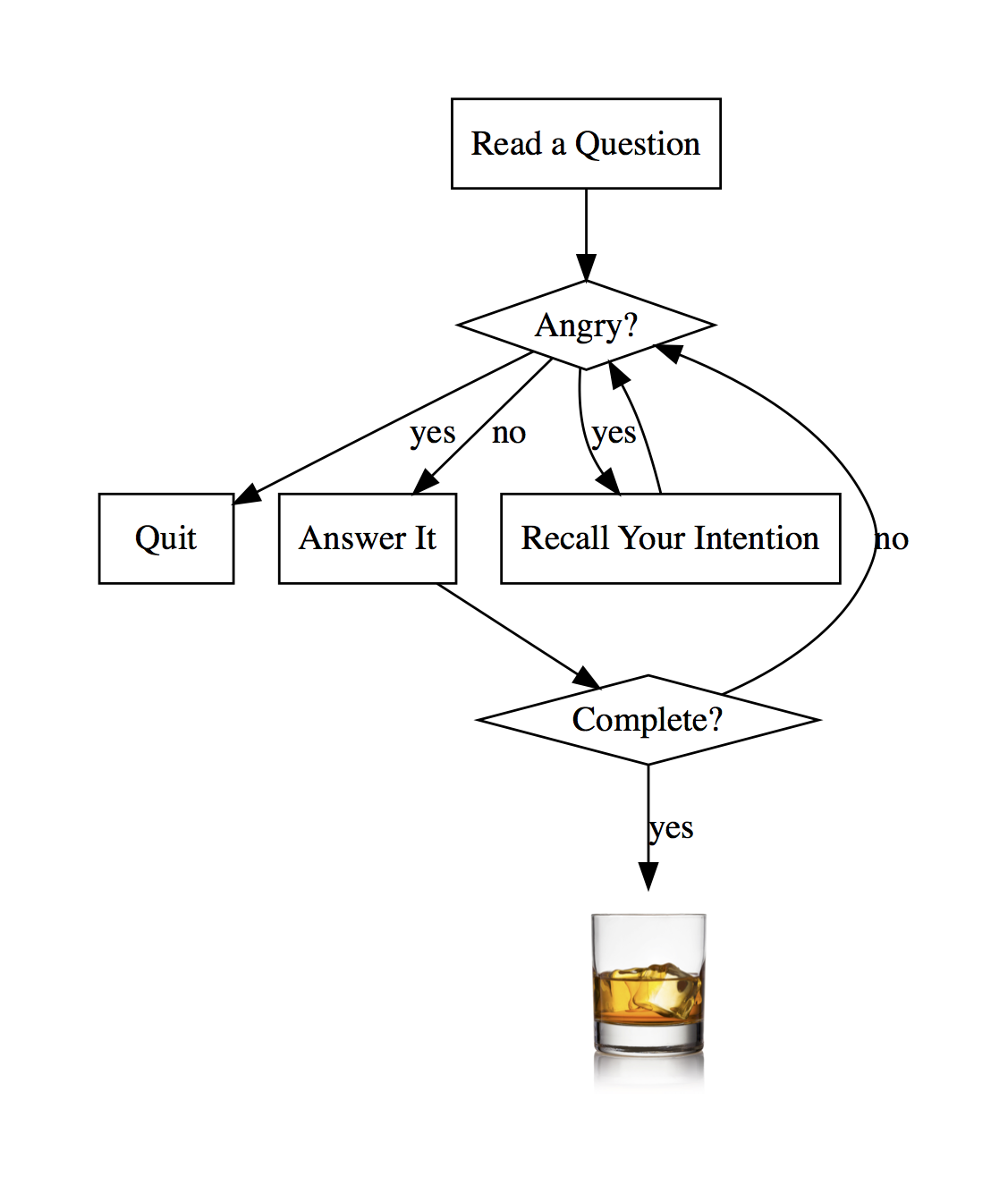

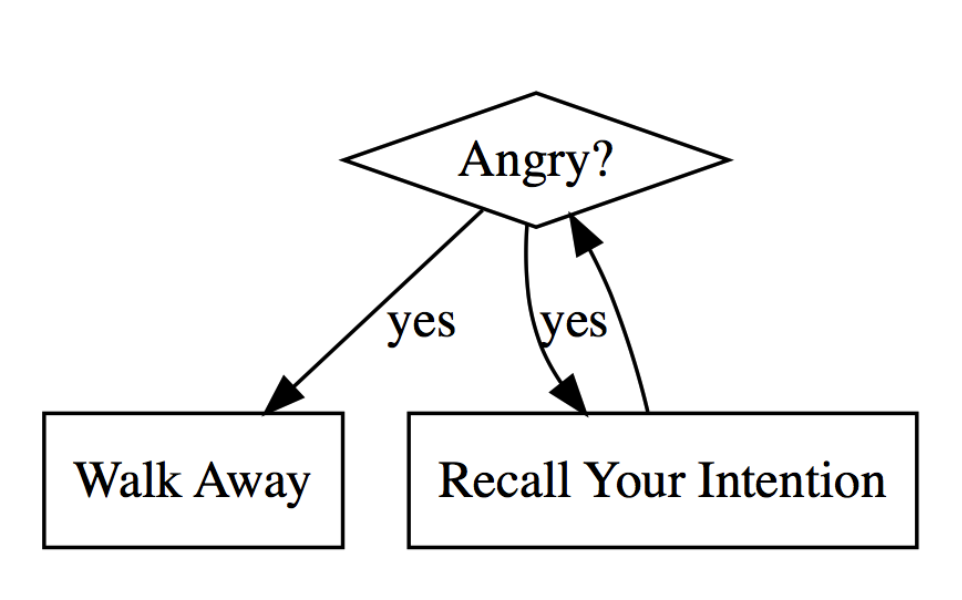

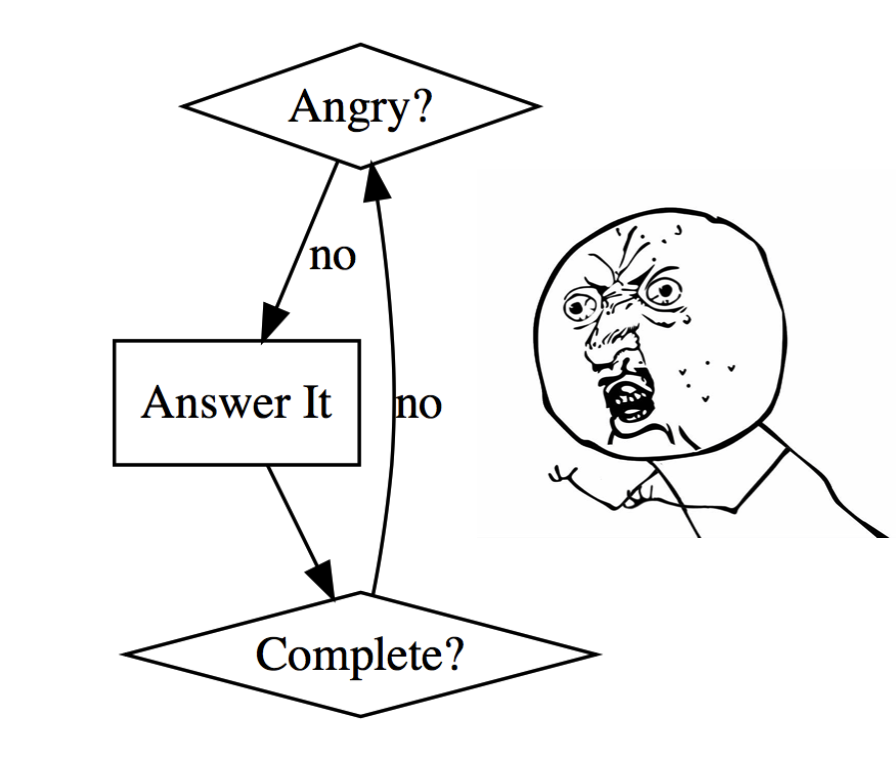

This talk is for you and me. We join communities with the intent to be generous to newcomers and then something goes wrong. So, we are here today to figure out how to prevent that from happening. And because I’m a nerd, I made a flowchart with GraphViz. It starts at the top and you read a question, and then maybe it makes you angry. And then you’ve got some options. You can walk away, or you can recall your intention, you can remember what you’re doing here and then check again. Am I angry, still or not? If you’re not, then you can complete answering the question then you can get your reward, whatever it is. For me, it’s a glass of whiskey.

Now what is the most important step in this flow chart, do you think? I think it’s the step where you ask yourself, ‘Am I angry or not?’ In person, it’s easy. If I’m face to face with you and you ask me a question and I get angry, I feel myself. I feel myself breathing, my neck gets tense. But when you’re online, you’re just typing, and you’re not aware of your body at all. I think that this is part of the reason why we behave so much worse online than we do face to face. We’re not feeling our bodies while we’re communicating. So, ask yourself, ‘How do I feel? Am I angry or not?’ And then, if you are, remember you can just walk away. There’s no reason that just because you started answering a question that have to finish it. Just because you read something on Stack Overflow it doesn’t oblige you to stay there. In the United States, we have this saying, ‘If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.’ I think that is a perfect principle to apply online. Somebody else will answer it, somebody who is not angry.

But maybe you’re angry but you want to get over it. You still want to answer this question because it’s your job or you have an intention of nurturing new programmers. How do you stop being angry? The thing that works for me is just to remember my intention. What was I doing here in the first place? I think that there’s about three intentions for me, that bring me to Stack Overflow or mailing lists to answer beginners’ questions. The first of these intentions might simply be that it’s my job to answer questions. It’s my job to answer questions about MongoDB and Stack Overflow, for example. Or it’s my job to answer questions about using Python and MongoDB on the mailing list. And I want to do my job well.

Another thing is, you might not be paid to answer questions about an Open Source project, but you care about that project and you want people to use it correctly. So, you care about your code and you want to take good care of it. Maybe that’s your intention. Or you just want to nurture new programmers in general. Maybe you’re answering questions of basic Python usage in Stack Overflow. Why are you doing that? I do that because I want to nurture the next generation of programmers and also to use Python as a way of increasing access to computer science for everybody who wants to learn how to code.

So, once you’ve remembered what you were doing here, check in again. Am I still angry, or not? If you stopped being angry because you remembered why you were trying to answer this question in the first place, then you’re ready to go ahead and answer it. I have a basic, basic technique that will you off to the right start. So, let’s say you’re reading this Unicode question. You’re going to answer it. It doesn’t matter whether this is a good question or a bad question, or a basic question or an advanced question. Open that text box and type, ‘Good question.’ Makes you feel good, makes the other person feel good. It gets everything off to the right start.

We’re going to do another interactive exercise. You’re going to have the same partners as you did before but we’re going to switch roles. So, now it’s the person on the right. You’re going to say, ‘How do I convert from PNG to GIF in Python?’ And now, the person on the left, you’re just going to say, ‘Good question!’

How does it feel to say, ‘Good question’? And how does it feel to hear, ‘Good question’? It gets things off to the right start. It doesn’t matter if it was actually a good question or not.

Now, here comes another dangerous spot. What if you have answered the question but the person who asked it doesn’t understand or asks a follow-up question? Or needs you to explain it more clearly. You thought you were going to be done, but you aren’t. I find this infuriating. This is what happened to me a couple years ago on Slack when I lost my temper with that new colleague of mine. I thought I’d answered his question, but then he asked a follow-up question and he wanted me to make more of an effort. I responded with sarcasm and cruelty.

So, if you’re not complete again, you’ve got to go back to the top and take three more breaths. Ask yourself, ‘Am I angry or no?’ Here I think it’s helpful to just put yourself in the other person’s shoes. Remember what it felt like today when somebody called you lazy and stupid. You don’t want to put somebody else in that position. Or just remember when you were first learning something, anything. You were first learning a language or you were first learning how to program computers at all. Just remember that everybody starts somewhere. Treat everybody with the respect that they deserve.

The Reward #

And now, if you manage to drive the conversation to completion, it’s some for your reward. And for me, the reward is a glass of whiskey or whatever you want, glass of wine, tapas; it’s up to you. But the outcome of treating newcomers well is what we’re here for. It’s the best.

I think about my colleague at MongoDB, a woman who I trained when she first joined MongoDB, named Asya Kamsky. She joined MongoDB when we only had 30 or 40 employees. We were all doing everything and I was doing the initial technical training for new hires. I was teaching them how MongoDB works internally. Asya took this class from me and I couldn’t figure out what was her deal. She was a funny Russian lady. She wasn’t like anybody else in that class. She kept interrupting me to ask these basic questions. I would be explaining something about MongoDB and she would say, ‘Hold on, hold on, wait. Start over again. Break it down for me. What are you really saying?’ But I never lost my temper with her. I was respectful. And I had some advantages. First of all, we were face to face. We were in a room and that makes it easy to treat people respectfully. And also, I was doing my job that day. It was my job to teach this class, so I knew that I was going to be there all day no matter what. So, it was easy to be patient with her. And I’m so glad I was, because it turns out Asya was already an extremely experienced engineer, far more experienced than me when she was taking my class. She just didn’t know how MongoDB worked.

Asya’s one of the smartest people I’ve ever worked with, and she’s now one of the most valuable colleagues that I have. She’s the lead product manager. She’s given talks about MongoDB that are most popular and highest rated of any MongoDB talks. But imagine if I had treated her disrespectfully when she was asking those basic questions at first. Asya can work anywhere and she might have just quit. I would have, if I were her and somebody disrespected me. I don’t want to work for a company where people are mean to each other. But because I treated her well when she was first starting out, she has proven to be one of the most valuable people at MongoDB.

So, this is what we get from treating people well. This is the ultimate reward. First of all, that we cultivate our community. We keep that line moving up and to the right. We keep Python growing and that makes our own skills more valuable. We also welcome new members, people who might not be sure that they belong with us. We reassure them that there’s no such thing as a stupid question. We will treat the most basic questions from the newest programmers respectfully and well. That helps us use Python to create an inclusive and diverse community around writing code. And finally, it just feels good. It feels good to be part of a community where people treat each other with respect. It’s the kind of community that I want to be a member of.

The Three-Breath Vow #

I’ve got one takeaway for you from this talk. You don’t have to memorize the whole flow chart. You just have to remember this. I invite you, if you want, to vow to take three breaths before you answer questions online. If you’re ready, then please repeat after me:

I vow

to take three breaths

before I answer a question online.