Optimizing a Meditation Retreat with a SAT Solver

Well, a SAT solver can optimize the retreat schedule. A meditation retreat as a whole is a living creature, beyond any individual’s control. But I can provide a schedule that functions smoothly and reduces distractions. I used Python and integer programming, a technique for mathematical optimization.

The problem #

The Village Zendo holds two weeklong Zen meditation retreats every summer, and one every winter. An essential part of Zen retreats is interviews (“dokusan” or “daisan”) between students and teachers, where students can ask questions or present their understanding of koans. At a Village Zendo retreat, we want each student to see one teacher per day. We assign students to groups, and call each group out of the meditation hall to see a teacher at the start of a meditation period. Certain students serve as jishas; they’re in charge of calling a group of students and escorting them to the door of the interview room. The students in the group line up, and enter the room one at time for a short conversation with the teacher.

Besides ensuring one interview per student per day, there are many other rules and goals. Dear reader, if you’re a programmer, you are probably already beginning to model this as an optimization problem. The objects in the system are:

- Students. Some of the students are jishas, and some have other jobs which affect the optimization problem.

- Teachers. This summer there were 8 teachers for 35 students.

- Rooms. This summer there were 2 interview rooms. Our abbot used his own room for interviews.

- Groups. Each student belongs to one group.

- Slots. There are time slots for interviews in the morning, afternoon, and evening meditation periods.

The challenge is to assign students to groups, then schedule jishas to bring groups to teachers during slots, so that all groups see a teacher once a day. Ideally, a group sees a variety of teachers during the week, and the workload is spread evenly among the teachers, and evenly among the jishas.

For the last few years my fellow Zen student, the mathematician Volker Kenko Ecke, had been manually solving this problem for each retreat with a big spreadsheet. He assigned students to groups, groups to slots, etc. by hand, then wrote formulas to check that all the rules and goals were satisfied. It was impressive, but I felt the itch to automate it. This is the difference between mathematicians and programmers.

Translating the problem into SAT #

Last summer I offered to write a program. This was not a problem for LLMs. I vaguely knew that a SAT solver was the natural tool. I chose Google’s open source CP-SAT solver, which solves integer programming problems: optimization problems involving assigning integers to variables, constrained by simple formulas. It has a nice Python API.

To translate the interview scheduling problem into Solverese, I made two big binary matrices. One is group assignments: the columns are groups, the students are rows, and there’s a 1 wherever a student is assigned to a group and 0 everywhere else.

students = [

Student(last="Davis", first="Jesse", dharma_name="Jiryu"),

Student(last="Cohen", first="Steven", dharma_name="Jindai"),

# ... and so on ...

]

MAX_STUDENTS_PER_GROUP = 5

groups = [Group(number=i) for i in range(ceil(len(students) / MAX_STUDENTS_PER_GROUP))]

from ortools.sat.python import cp_model

model = cp_model.CpModel()

# Matrix of bools, each is true if a student is part of a group.

group_assignments = {

(st, g): model.new_bool_var(f"{st.display_name} group {g.number}")

for st in students for g in groups}

As you can see, you create a variable with model.new_bool_var. Later I’ll show you how these are used in constraints like “each student is in exactly one group.”

Besides the two-dimensional group assignment matrix, the other binary matrix has four dimensions: teachers, jishas, groups, and slots. If a certain jisha takes a certain group to see a certain teacher at a certain time slot, then that cell of the matrix has a 1, otherwise 0. I called these combinations shifts.

# Matrix of bools, each is true if a teacher, jisha, and group is assigned

# to a slot. # Key is a Shift object, value is a variable to which the

# solver assigns a value.

shifts = {Shift(t, j.display_name, g, s): model.new_bool_var()

for t, j, g, s in product(teachers, jishas, groups, slots)}

Creating a schedule is equivalent to assigning 1s and 0s to the cells in these two matrices, in a way that satisfies all the constraints and optimizes some goal. So I started adding constraints.

Expressing constraints #

First, a student can only be in one group. That means the sum of group assignments along a student row is 1:

# Each student is in 1 group.

for st in students:

model.add(sum(group_assignments[(st, g)] for g in groups) == 1)

And each group can only have MAX_STUDENTS_PER_GROUP members:

for g in groups:

# Enforce MAX_STUDENTS_PER_GROUP.

model.add(sum(group_assignments[(st, g)] for st in students)

<= MAX_STUDENTS_PER_GROUP)

Giving interviews is tiring for teachers, they should only have one shift per day. For each teacher/day combination, I create an integer variable with model.new_int_var, constrain it to equal the number of shifts for that teacher on that day, and also constrain it to be less than or equal to one:

days = list(sorted(set(s.day for s in slots)))

for t in teachers:

n_teacher_shifts = sum(

v for s, v in shifts.items() if s.teacher == t)

for d in days:

shifts_today = model.new_int_var()

model.add(shifts_today == sum(

v for s, v in shifts.items()

if s.teacher == t and s.slot.day == d))

model.add(shifts_today <= 1)

There are a dozen other rules, and they’re all similarly easy to express. For example:

- A teacher can only see one group per slot.

- The abbot prefers to do interviews only in evening slots.

- The abbot has a particular jisha; other jishas are free-floating.

- Jishas should only do one shift per day.

- Each group should get one interview per day, and see each teacher only once during the retreat.

- Since there are two interview rooms, so only two teachers can do interviews per slot (but the abbot uses his own room).

- Some students are monitors. At least one monitor should be in the meditation hall at all times.

- … and so on.

Once I banged the model into shape, I told the solver to find a solution:

solver = cp_model.CpSolver()

# Determinism.

solver.parameters.random_seed = 1

# Stop trying after about 5 minutes - but use a virtual clock

# that always stops after the same number of operations.

solver.parameters.max_deterministic_time = 300

solver.parameters.num_workers = 1

status = solver.solve(model)

The “determinism” arguments ensure I get the same solution each time I run the same code, which helps me debug.

Refinements #

Once the program basically worked, I generated a PDF of the schedule and the group assignments, and made some improvements. For example, could I reduce the jishas’ workload? A jisha leaves the meditation hall for two reasons: if she leads a group of students to see a teacher, and also if her own group is called to see a teacher. On past retreats, a jisha might lead Group 1 to Teacher A, while her own Group 2 was seeing Teacher B. This led to hectic improvisation; not very peaceful. I called these “jisha conflicts” and told my program to eliminate them. This was a bit complex. Recall that every “shift” is a combination of teacher, jisha, group, and slot. So for every shift S1, and every other shift S2 with the same slot but a different group, either S1’s jisha isn’t in S2’s group, or S2’s group isn’t doing interview during this slot.

# Avoid jisha conflicts: when a jisha is serving one teacher while

# their group is called # for another. To prevent conflicts, if a

# jisha j is assigned to a shift it implies # j isn't in groups seen

# by other teachers in that slot.

for shift in shifts:

for t, j, g in product(teachers, jishas, groups):

if g == shift.group:

continue

# Another shift with the same time slot but different group.

other_shift = shifts[Shift(t, j.display_name, g, shift.slot)]

# If shift is true, then other_shift is false or shift's jisha

# isn't in other_shift's group.

j_in_other_group = group_assignments[

(name2student[shift.jisha_name], g)]

model.add_bool_or([

j_in_other_group.negated(),

other_shift.negated()

]).only_enforce_if(shifts[shift])

This was slightly mind-bending to code, but it only took a few hours of thinking and reading the CP-SAT docs. It eliminated a historical source of stress for the jishas.

I wondered, could I simplify jishas’ lives even more? For each jisha I calculated the number of extra trips she took out of the meditation hall: i.e., the number of times she led out a group of students besides her own. I told the model to minimize the sum of the squares of the extra trips, so it would try to both reduce the workload and spread it evenly. It’s about 20 lines of code, and it reduced the average jisha’s time out of the meditation hall from 3 trips to 0 or 1. This was another big improvement over past retreats.

As I said, a SAT solver can’t optimize your meditation, but it can help create good conditions!

Minimizing changes #

I’ve been on dozens of Zen retreats, and I’ve been involved in organizing some of them. Constant change is the norm, just like Buddha taught. People join late, leave early, get sick. And maybe we realize partway through the retreat that we should change the program, add a new constraint or goal we didn’t think of until we put the schedule to use. Once my program had made a schedule, I knew it wouldn’t be “final.”

So, each time the program runs, it checks the time. If the retreat hasn’t started, it can make a new schedule from scratch, freely reassigning groups and shifts. Once the retreat starts, the groups are permanent, and the program must do its best to meet its goals without changing group assignments. Shifts are malleable so long as they’re in the future, but the program knows it can’t change the past. So if we suddenly decided some group of students must see the abbot, the program can satisfy that only by changing shifts starting after the current time.

Retrospective #

I’ve scheduled four weeklong retreats with this program, improving the code each time. (I put a version with participants’ names redacted on GitHub.) I’ve learned what questions to ask the registrar, the abbot, and the retreat managers before the retreat begins, so I create a schedule that fits their requirements. I still have to personally edit and run the code—this is a script, not a software product—but it’s becoming routinized.

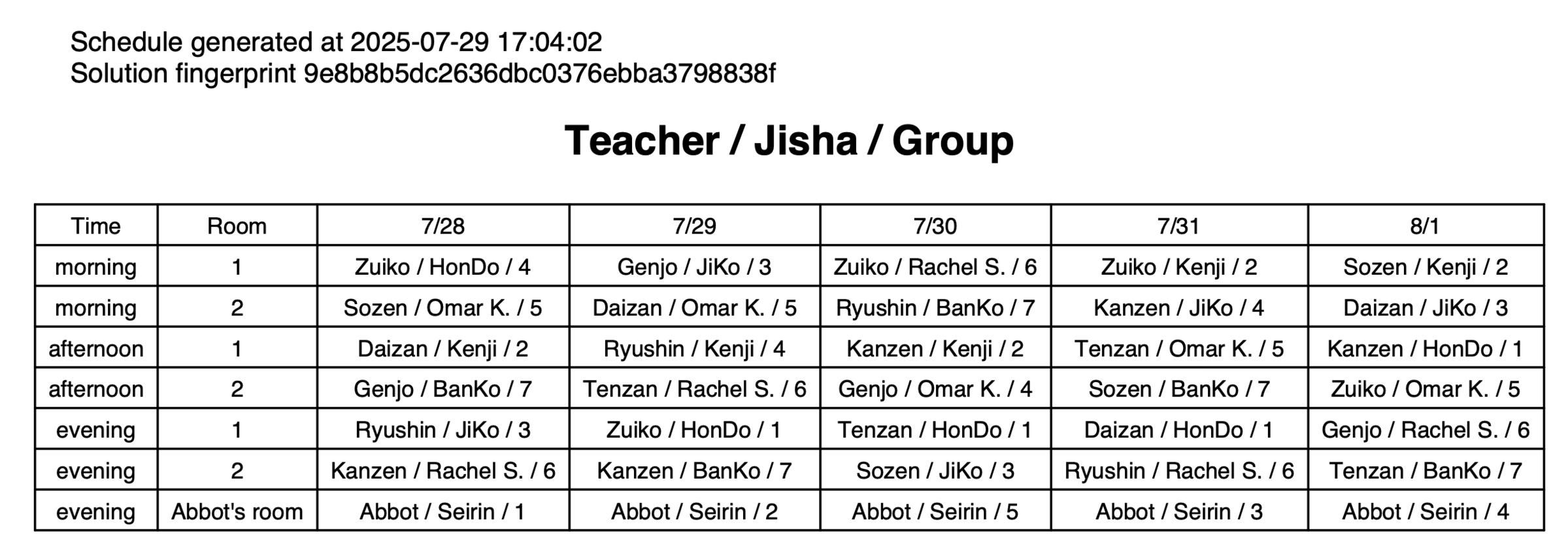

The program generates a nicely formatted PDF of the schedule, that we can print out and post on the wall at the retreat center:

The PDF includes a timestamp and a fingerprint (a hash of all the variable assignments), to avoid confusion when there are multiple printed copies floating around among the retreat staff.

The program also generates a PDF of group assignments, and a card with each student’s individual schedule. It also outputs a text file with statistics, like how many shifts each teacher and jisha has, so that the retreat managers and I can evaluate the quality of the solution.

The smartest decisions I made were the first ones: to encode the schedule as two boolean matrices and use a SAT solver. Now, I hardly ever have to think, “How do I solve this problem?” I only have to figure out, “How do I express this constraint or goal in terms of CP-SAT?” Furthermore, I spend little time checking the solution. If I code a new constraint, then I spend a few minutes checking that the latest schedule satisfies it as I expect, but after that I mostly trust the program. Even when I make a consequential change, like adding a constraint or removing a day, I’m confident the program will rearrange the puzzle pieces to fit. If I had tried to write my own scheduling algorithm, changes would be much harder and riskier.

I was particularly satisfied last week, when a teacher got sick and canceled on the first day of retreat. With the old handwritten spreadsheet, I think it would’ve been hard to adapt the schedule, and there wouldn’t be enough time to make a really good one. But now that it’s automated, I simply deleted the sick teacher and reran the program. It found no solution, so I relaxed a constraint—now some teachers will have to take two shifts per day—and voilà, a perfectly good new schedule popped out 5 minutes later.

Images: My photos from Village Zendo retreats. All rights reserved.