Paper Review: Programming as Theory Building

If you’re my colleague and you want to trigger my most ferocious pet peeve, ask me to explain something that I’ve already written down. My first response will be a terse link to the docs. I won’t say “RTFM” out loud, but if you listen closely you can hear me think it. If you ask a followup that I’ve also written the answer to, I get sarcastic and rude. Things generally devolve from there.

My pet peeve, when triggered.

Until now I’ve felt justified nurturing this pet peeve. If it bites you, that serves you right for not doing your research before you bothered me. But I’ve just read something that changed my mind.

In his 1985 article “Programming as Theory Building”, Peter Naur (of Backus-Naur form) says a programmer’s main activity isn’t coding, it’s creating a theory of the problem at hand and its solution. This theory is implicit knowledge, which can’t be written down. Sure, I can transmit some knowledge via documentation. But you can’t understand my code as well as I do unless you acquire the theory I built in my head, and you can’t get that by reading my docs or my code. I can’t acquire your theories by reading your writing, either.

Peter Naur.

Naur says that a theory is “the knowledge a person must have in order not only to do certain things intelligently but also to explain them, to answer queries about them, to argue about them, and so forth.” (He’s borrowing a definition of “theory” from philosopher Gilbert Ryle.) This sounds like the kind of knowledge I have about my own software designs, but not about anyone else’s.

Why can’t I write down my theory? Naur says “the programmer’s knowledge transcends that given in documentation in at least three essential areas”:

- The programmer knows how the real world maps to the program, and which parts of the world are relevant to the program or not. Naur claims this can’t be captured in text.

- The programmer can explain all design decisions. “The justification is and must always remain the programmer’s direct, intuitive knowledge or estimate.” Even if I followed some well-known design principle, my choice of which principle to apply was intuitive, not based on a principle-choosing rule that I can write down.

- The programmer knows how best to modify the program to meet new requirements. This depends on recognizing similarities between new and old situations; these similarities “are not, and cannot be, expressed in terms of criteria, no more than the similarities of many other kinds of objects, such as human faces, tunes, or tastes of wine, can be thus expressed.”

I’m ambivalent about these arguments. On the one hand, my experience matches Naur’s: I seem to know something about my designs and code that others don’t, and others know something about theirs that I don’t, and no amount of documentation alters this. On the other hand, I cling to the belief that better writing could capture more of this knowledge. The designs I write today are not the best explanations possible. Each of my design docs gets frozen as soon as I achieve consensus among my dozen reviewers; it’s a ceasefire line, not a friendly guidebook. If I took the time to write the guidebook after the design is approved, and I encouraged everyone to read the guidebook instead of the design, maybe I’d transmit this theory that Naur thinks is so ineffable.

When a design debate ends, the document is a record of when the shooting stopped, not a clear explanation. (The Somme.)

But let’s say Naur’s right: a theory can’t be written. This implies that to modify a program, you must hire people who possess the theory, usually the program’s original authors. Otherwise each change by programmers who don’t possess the theory adds to the program’s decay, until it is unmaintainable. “The death of a program happens when the programmer team possessing its theory is dissolved…. [R]eestablishing the theory of a program merely from the documentation, is strictly impossible.”

It reminds me of Zen. Bodhidharma described it thus: “A special transmission outside the scriptures. No dependency on words and letters.” As in Zen, a programmer can speak from her understanding, though not of her understanding. Naur: “[T]he person possessing a theory will be able to produce presentations of various sorts on the basis of it, in response to questions or demands.”

Does that make me indispensable? Must I answer questions about my designs and code until I quit or die, leading to my software’s death? No, a theory is transmissible (like Zen):

What is required is that the new programmer has the opportunity to work in close contact with the programmers who already possess the theory…. This problem of education of new programmers in an existing theory of a program is quite similar to that of the education problem of other activities where the knowledge of how to do certain things dominates over the knowledge that certain things are the case, such as writing and playing a music instrument. The most important educational activity is the student’s doing relevant things under suitable supervision and guidance.

So it’s not mystical after all; it’s pretty ordinary. A theory includes some implicit/functional knowledge, not just explicit/propositional knowledge, and the implicit knowledge must be transmitted by mentorship.

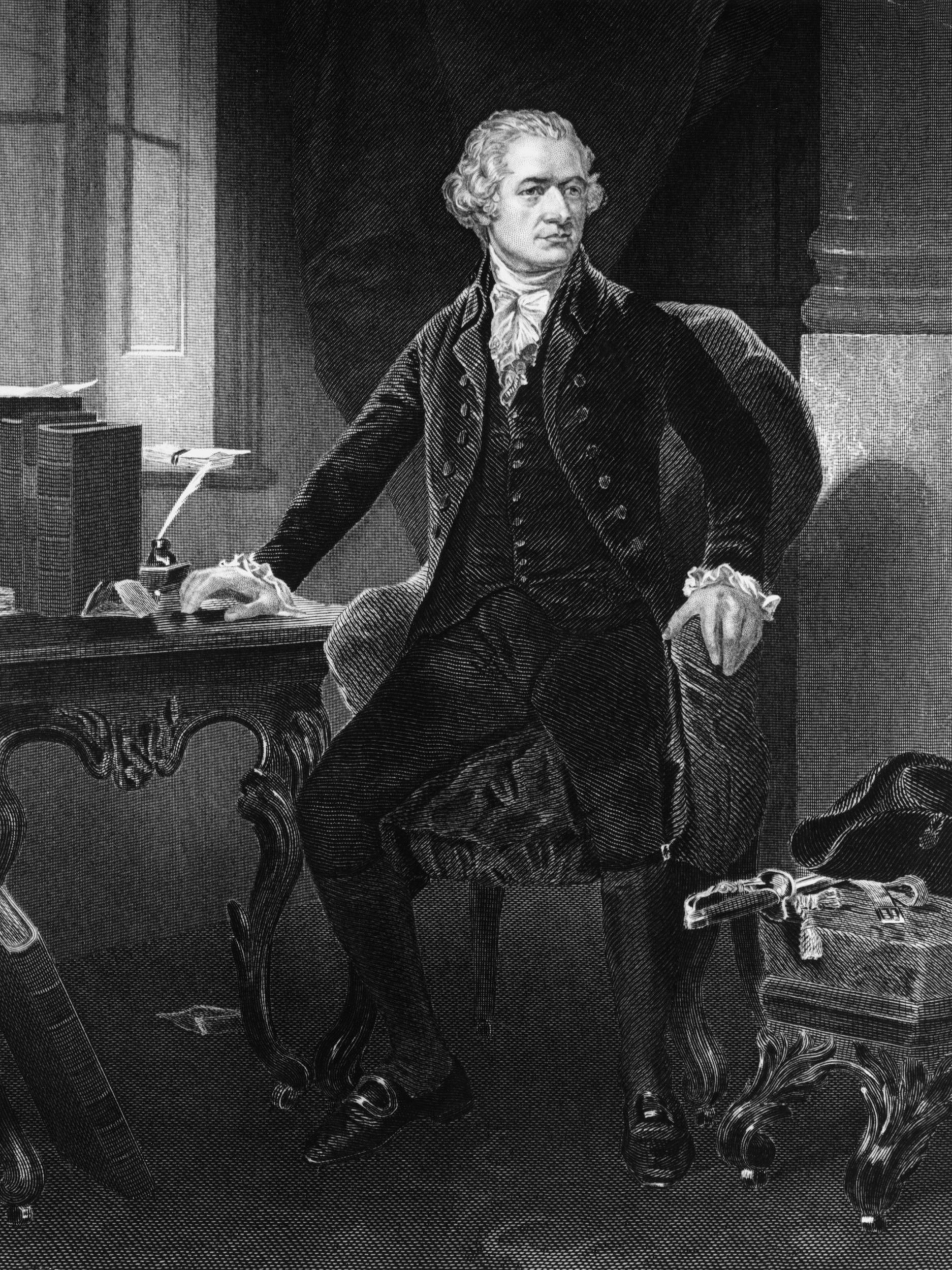

Until now, my goal when I wrote designs was to preempt all questions. If you’re my colleague, I thought you should be able to read the design (or a blog post or wiki page) and learn everything you need. Like Hamilton, I tried to write my way out of most situations. If you had read my document and still had questions, I’d write more! Until “Programming as Theory Building” I didn’t know why this didn’t work. If I believe Naur (and I half do), then I have to deliberately transmit each of my theories by working closely with the individuals who want to acquire them.

Alexander Hamilton.

What about my pet peeve? I feel less justified snapping at you for asking me questions. It’s a fact of life that we can hold more subtle knowledge in our heads than we can express in language, so we have to play Twenty Questions and Charades trying to find the outlines of each other’s knowledge. That’s a lonely fact, but at least we’re all lonely in this together. I don’t know your theories any better than you know mine.