Review: Distributed Transactions at Scale in Amazon DynamoDB

Distributed Transactions at Scale in Amazon DynamoDB, USENIX ATC 2023. This paper builds on last year’s DynamoDB scalability and reliability paper. It’s unrelated to the obsolete Dynamo system described in 2007. The current paper describes how Amazon added transactions to their existing key-value store. Their requirements were:

- ACID, where “C” is serializable, but not strict serializable: transactions can appear to happen in any order. This will be important.

- Transactions update items in-place, rather than creating new version of items. Their existing storage layer didn’t have MVCC and they didn’t want to add it.

- Large scale. DynamoDB does non-transactional operations at record-breaking volume, and they expect to support a monstrous throughput of transactions too.

- Don’t hurt the performance for the single-key (non-transaction) operations they already support.

“The challenge was how to integrate transactional operations without sacrificing the defining characteristics of this critical infrastructure service: high scalability, high availability, and predictable performance at scale.”

DynamoDB is a key-value store, built on sharded, replicated storage nodes. The shards use MultiPaxos for consensus and fault-tolerance.

Clients can send four kinds of non-transactional requests to storage nodes: put, update, delete, and get. These are single-key operations and not transactional, and each runs on a single node. Routers (not shown) find the right node for each request.

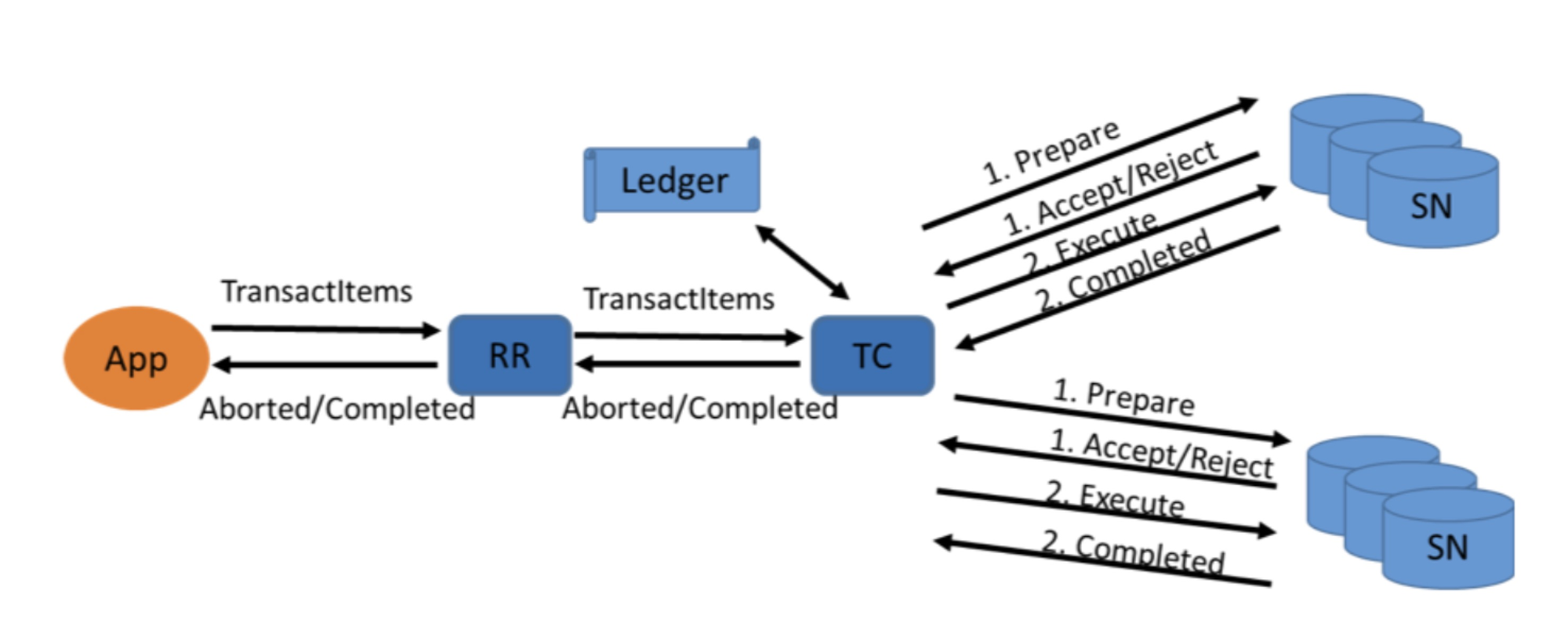

Transactions, however, can involve multiple keys and therefore multiple storage nodes. There are lots of transaction coordinator nodes, each transaction can use any one coordinator.

Coordinators are replicated for fault tolerance. If a coordinator goes down during a transaction, one of its backups takes over and continues.

Transactions API

The DynamoDB engineers decided not to support conversational transactions like in SQL. Instead, they have a one-shot transaction API. Here’s an example for writes. (Listing 1 from the paper; I’ve edited for clarity.)

// Check if customer exists

Check checkItem = new Check()

.withTableName("Customers")

.withKey(...)

.withConditionExpression("attribute_exists(CustomerId)");

// Insert the order item in the orders table

Put putItem = new Put()

.withTableName("Orders")

.withItem(...)

.withConditionExpression("attribute_not_exists(OrderId)");

// Update status of the item in Products

Update updateItem = new Update()

.withTableName("Products")

.withKey(...)

.withConditionExpression("expected_status" = "IN_STOCK")

.withUpdateExpression("SET ProductStatus = SOLD");

TransactWriteItemsRequest twiReq = new TransactWriteItemsRequest()

.withTransactItems([checkItem, putItem, updateItem]);

DynamoDBclient.transactWriteItems(twiReq);

There are three operations here (check, put, update), which are packaged and sent to the coordinator in one shot. If any condition (highlighted lines) is false, the whole transaction is aborted. So this series of operations is a tiny program that can enforce invariants, like “a product appears in at most one order”.

Write Transactions

Here’s the algorithm that each storage node runs to prepare a transaction, once for each item involved. (Listing 2 from the paper, edited).

def processPrepare(PrepareInput input):

item = readItem(input)

if item != NONE:

if evaluateConditionsOnItem(item, input.conditions)

AND evaluateSystemRestrictions(item, input)

// No committed transaction with later timestamp:

AND item.timestamp < input.timestamp

// Not already read/written in a prepared transaction:

AND item.ongoingTransactions == NONE:

item.ongoingTransaction = input.transactionId

return SUCCESS

else:

return FAILED

else : #item does not exist

item = new Item(input.item)

if evaluateConditionsOnItem(input.conditions)

AND evaluateSystemRestrictions(input)

// No txn has deleted *anything* with later time

AND partition.maxDeleteTimestamp < input.timestamp:

item.ongoingTransaction = input.transactionId

return SUCCESS

return FAILED

This is optimistic concurrency control: the write transaction doesn’t lock any items, to avoid blocking non-transactional operations. Instead, the coordinator assigns a timestamp to the transaction (input.timestamp) from its local clock, and the storage node checks if any later-timestamped transaction involving the same items has committed; if so it returns FAILED, which causes the coordinator to abort the transaction. The storage node also returns FAILED if an item’s ongoingTransaction field is set, meaning another transaction involving the same item is in the prepared state.

Notice that if a concurrent, later-timestamped transaction deletes any key in the same partition as this item, it aborts this transaction. The authors say deletes are rare enough that this is okay. Otherwise, they could replace each deleted key with a specific tombstone, but then they’d have to garbage-collect the tombstones, which would be less efficient for their workloads.

The “prepare” phase is part of a larger protocol, the classic two-phase commit. The client sends its request to a request router “RR”, which sends it to a transaction coordinator “TC”. The coordinator persists the transaction info to a replicated ledger, then it tries to prepare the transaction on all the storage nodes. They all write the transaction’s id to all the involved items' ongoingTransaction fields, both the items read and the items written. If successful, that means no other transaction involving those items can prepare. Then the coordinator tells the nodes to commit, so they all write the transaction’s timestamp to the involved items and clear ongoingTransaction. Finally, the coordinator acknowledges the transaction to the client.

If the coordinator aborts a transaction, it clears ongoingTransaction but leaves the items' timestamps unchanged.

So long as each transaction appears to occur at some point in time, without interleaving with any other transaction, serializability is guaranteed. The prepare algorithm we saw ensures that.

Clock skew will cause extra transaction aborts. (And maybe “external consistency” violations?) But clock skew won’t cause DynamoDB to violate serializability or any other stated guarantees.

By the way, what happens if two coordinators start two transactions at the same timestamp (within their clocks' precision)? The paper doesn’t discuss this; I’d assign a unique id to each coordinator, and append this id to each timestamp to deterministically resolve ties.

I think that non-transactional writes (including deletes) must be blocked or aborted by prepared transactions on the same keys, but the paper doesn’t specify. Additional interactions between transactions and non-transactions are described in the optimizations section.

Read Transactions

DynamoDB’s read-only transactions have a distinct implementation from write transactions. Read transactions could use the same protocol as write transactions, but the authors say they didn’t want to update item timestamps on read, because updating the timestamp is an expensive replicated write.

Most modern databases have MVCC, so read-only transactions just read a recent past version of the data, providing snapshot isolation. But DynamoDB doesn’t have MVCC. The authors didn’t want to use read locks, either. They could update every key’s timestamp when it is read, to track read-write conflicts, but that would make every read into a costly replicated write, which the authors wanted to avoid. So how do read transactions work?

DynamoDB uses an optimistic concurrency control algorithm which aborts read transactions if they’re concurrent with any write transactions on the same items. The paper doesn’t include pseudocode for read transactions, so I wrote this:

def processRead(input):

items1 = readItems(input)

for x in items1:

if x.ongoingTransactions != NONE:

# A prepared transaction is writing.

return FAILED

items2 = readItems(input)

for x, y in zip(items1, items2):

if x.logicalSequenceNumber != y.logicalSequenceNumber:

# A transaction wrote to data in the read set.

return FAILED

return items2

The transaction coordinator reads all items, then reads them all again. If any are involved in a prepared transaction (just during the first read?) the transaction aborts. Each item has a logical sequence number (LSN) which increases whenever the item is changed, so the coordinator checks that all items' LSNs are unchanged between the first and second reads. If so, then the data the coordinator has read represents a consistent cut of the data at some point in the past, thus the coordinator returns its results to the client and upholds serializability. Otherwise it retries.

There’s an optimization where the coordinator doesn’t retry both phases of the transaction. It just assigns items2 to items1 (and re-checks if there’s an overlapping prepared transaction?), then re-reads items2, and compares LSNs again.

You can see I don’t totally understand the rules for prepared transactions. Plus I’m annoyed to see LSNs pop up here, when they haven’t been mentioned before. Could read transactions compare timestamps instead? Perhaps non-transaction writes update LSNs but not timestamps, so read transactions must compare LSNs to be certain that items are unchanged?

Optimizations

The paper’s Section 4 is two pages of little optimizations.

The classic timestamp ordering concurrency control scheme can be extended with novel optimizations when applied to a key-value store where reads and writes of individual items are mixed with multi-item transactions.

I’ll summarize and categorize their optimizations:

- Write transactions don’t block/abort single-key reads/writes, since the latter are always serializable and can be placed somewhere in the total order.

- Ignore a late-arriving write transaction if a later transaction just overwrites it. (Murat Demirbas points out this is the old Thomas write rule.)

- Same, for a batch of preparing transactions: if they all overwrite the same keys, pick one to commit and ignore the rest without aborting them.

- Single-partition transactions skip two-phase commit.

- Read transactions can have one phase if each item has a last-read timestamp. But isn’t that what the authors said they want to avoid? In a discussion, Alex Miller speculates they mean storage nodes can keep last-read timestamps in memory. They need not be durable; if there’s a failover, the coordinator can just retry the whole read transaction.

I’m peeved that the authors don’t say which of these optimizations they’ve implemented now, which they implemented before they ran this paper’s benchmarks, and which they haven’t implemented yet.

Their Evaluation

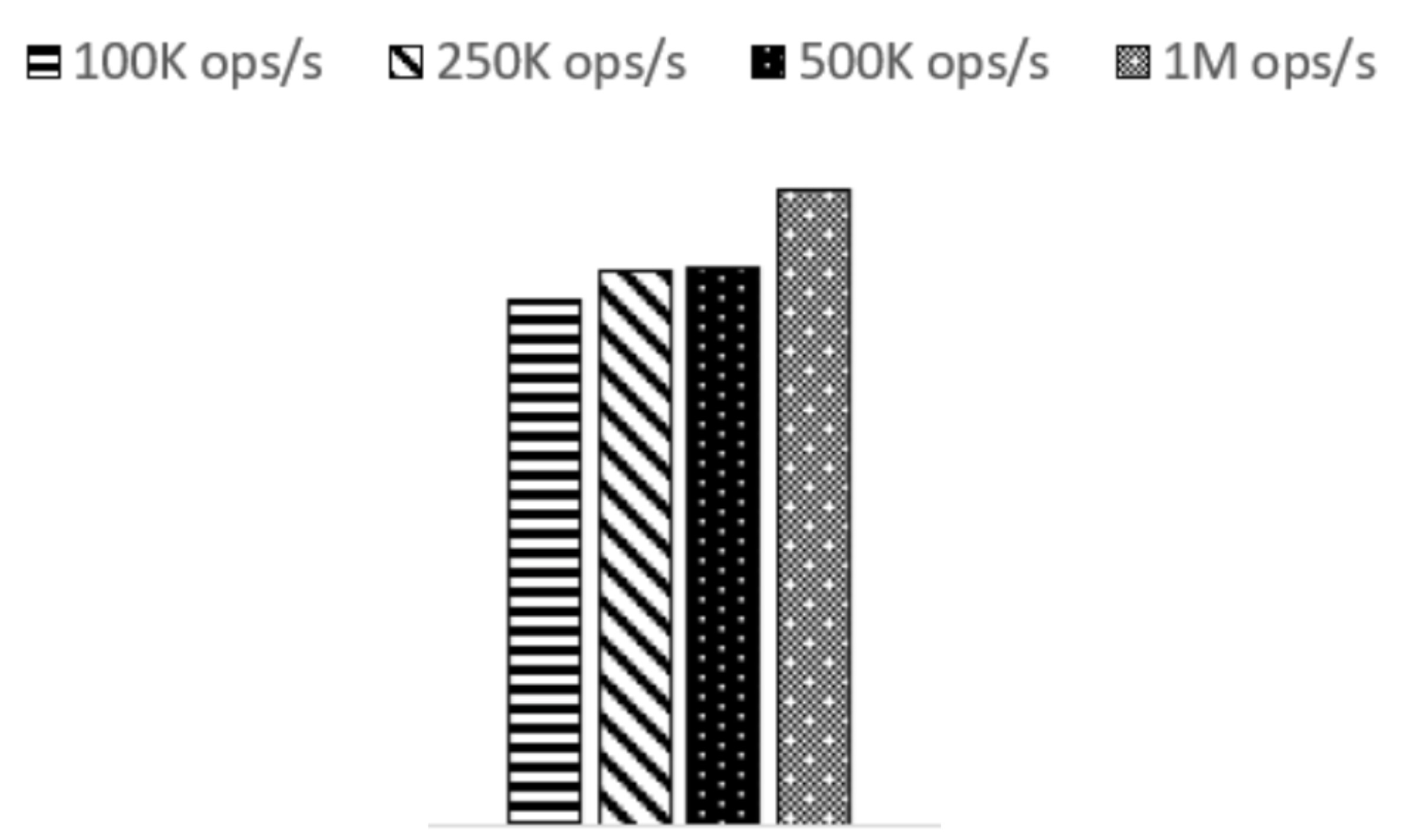

Amazon keeps their cards close to the chest. The authors don’t say what hardware they ran their benchmarks on, or how many routers or storage nodes they used. They show charts where the y axis is latency, but without any labels, so we don’t know what the actual numbers are. Judging by eye, it seems latency is virtually unaffected by the volume of transactions per second:

From Figure 4, p99 latency of half read/half write transaction workload

The slightly higher latency at very high load is due to Java garbage collection on the transaction coordinator. I’m really curious how many machines they used, and whether it was the same for the 100k workload and the 1M workload.

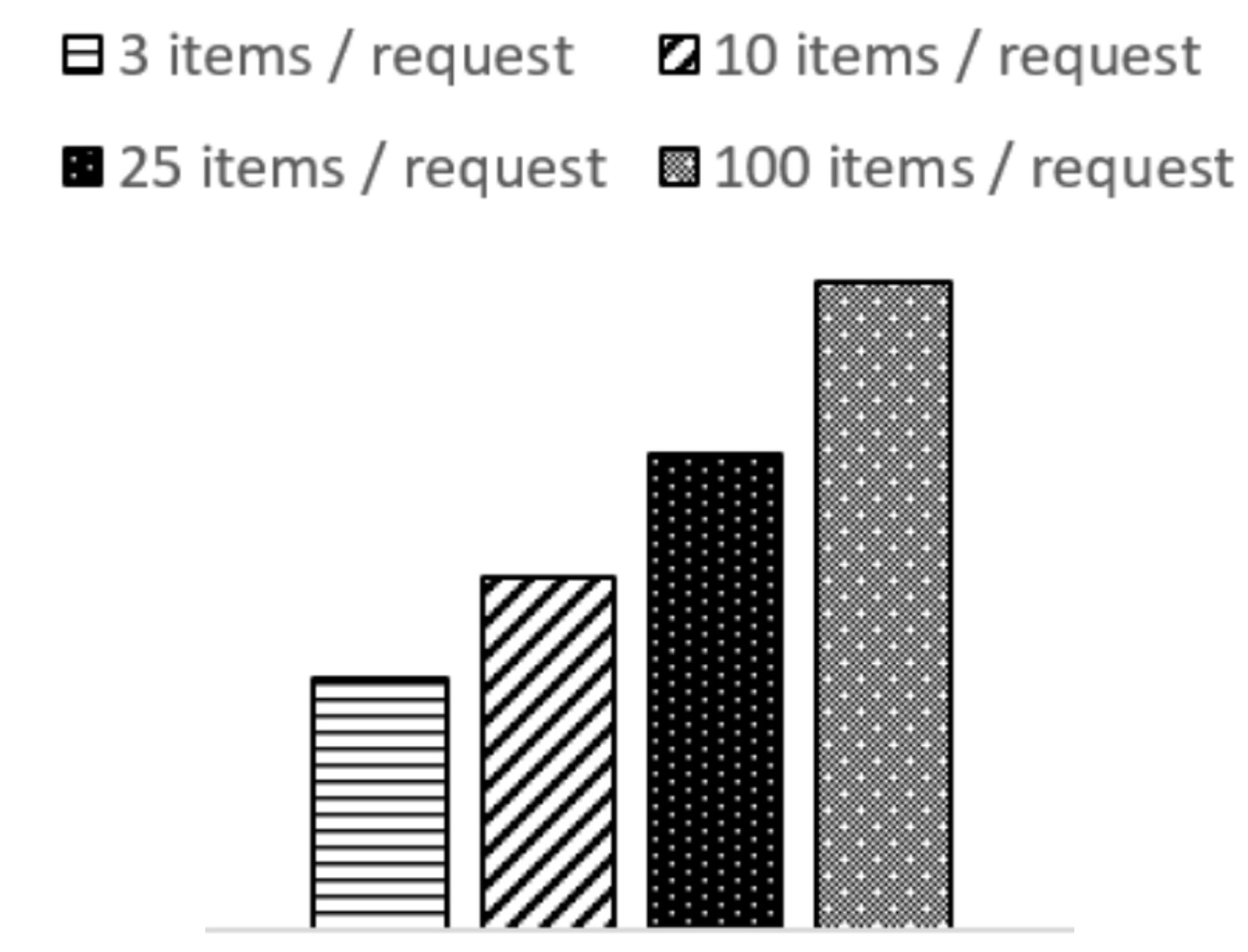

Holding the volume of transactions constant, latency increases sublinearly as the number of operations per transaction increases:

From Figure 6, p99 latencies for varying number of operations per TransactWriteItems

Again, we don’t know the Y scale for this chart, but presumably it’s linear. It shows that you can go from 3 items per write transaction to 100 items, and only double the latency. This is sublinear scaling, and DynamoDB accomplishes it by running each transaction’s operations in parallel. (This surprised me, since they didn’t mention parallelization when they described the transaction algorithms.) Latency does rise, because a large transaction has a higher chance of a slow operation. Plus, a big transaction takes longer to persist to the transaction ledger on the coordinator, and the request and/or response takes longer to transmit over the wire. Regardless, parallelization obviously works very well.

My Evaluation

The paper’s benchmarks show impressive scalability. But we don’t know what hardware they used. We don’t know if all the workloads use the same instance sizes and same number of partitions and coordinators. And of course we don’t know the actual latency numbers, because there’s no Y scale. It’s hard to be sure what the charts mean.

The one-shot transaction API could be tricky to use sometimes. For example, what if you want to read values from two items and store their sum?: a.x := b.x + c.x. You can’t express this in a one-shot transaction using DynamoDB’s API. It’s definitely possible to code this as a serializable operation, but it requires several round trips to the server, careful thinking, extra fields, and extra application logic. It reminds me of things we had to do with MongoDB to preserve constraints, before we had any transactions at all. The restrictions on DynamoDB transactions could make some application logic even trickier:

TransactWriteItemsis a synchronous write operation that groups up to 100 action requests. These actions can target items in different tables, but not in different AWS accounts or Regions, and no two actions can target the same item. For example, you cannot bothConditionCheckandUpdatethe same item. The aggregate size of the items in the transaction cannot exceed 4 MB.

I admire this paper, though. The authors faced unusual constraints, and responded with a thoughtful design that meets their goals. Timestamp ordering plus two phase commit is a classic style.

Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant in His Girl Friday

See also Murat Demirbas’s insightful summary.

Thanks to svgoptim for converting Excalidraw SVGs into something I can display on my blog with the font preserved.