Review: SelfTune: Tuning Cluster Managers

SelfTune: Tuning Cluster Managers, by authors from Microsoft Research, regular Microsoft, and Stony Brook University, at NSDI (Networked Systems Design and Implementation) 2023. Here’s a presentation I gave to the distributed systems reading group, a written version is below.

The only reason I review papers is because I like finding old images, here’s a guy tuning a piano.

The Problem #

This paper is about cluster managers, software systems like Kubernetes or Docker Swarm, that manage a bunch of servers (possibly in the cloud) to provide auto-scaling, high availability, geo locality, and so on. Cluster managers have a ton of config parameters. Tuning them by hand is a big effort, you might not find the optimal settings, and you have to keep tweaking them as conditions change. There are some existing auto-tuning systems, but the SelfTune authors say the existing systems either don’t find the true optimal config, or more importantly, they find it too slowly. It’s important to find a good local optimum fast, otherwise you’re wasting money or violating SLAs while running at suboptimal settings.

The Solution #

SelfTune is designed to find an optimal config quickly. It tunes live in production, without a separate experimental phase, thus SelfTune needs to balance “exploration” and “exploitation”: that is, it has to learn, but it mustn’t make lots of bad decisions in the process of learning.

It has a simple API for integrating self-tuning into your app. Here’s a code sample from the paper showing how it works (I’ve reformatted it and added comments). It uses SelfTune to configure some sort of job queue, which can process jobs in parallel, throttled by the number of “tokens” that are available.

public const double optLoad = 0.80; // target utilization

Config UpdateCycle = new Config(

"UpdateCycle", "TimeDelta", "00:00:01-00:00:30", "00:00:05");

// name type range default

SelfTune st = new SelfTune.Create(UpdateCycle);

// connect to a SelfTune server - could be one per host,

// or more centralized

st.Connect();

var currentLoad = 0.0;

while(1) {

// if underloaded, start more jobs, otherwise wait for jobs to finish

if (currentLoad < optLoad) {

int numTokens = GenerateTokens(currentLoad);

GrantTokensToJobs(numTokens);

}

Guid callId;

UpdateCycle = st.Predict(callId, "UpdateCycle");

sleep(UpdateCycle);

currentLoad = CalculateLoad();

// update SelfTune

// callId permits asynchrony

st.SetReward(callId, currentLoad - optLoad);

}

In this example, you initialize the SelfTune instance with the parameters it can tune (“UpdateCycle”), connect it to the tuning server, then enter a loop where you measure some reward function (how close load is to the desired level), ask SelfTune for its suggested parameter values, apply them, see how it impacts the reward, and report that back to SelfTune. The API looks nice and clean.

I thought the example of tuning “update cycle” was kind of odd though—wouldn’t you want to measure load as often as possible? When would a system perform better by sampling less frequently? Maybe there’s some other factor at play that should be addressed more directly in this example.

BlueFin algorithm #

SelfTune is an API and an architecture for tuning in production. There’s a pluggable learning engine in the middle of it; in this paper they use a specific learning engine called BlueFin. It’s a minimalist gradient ascent algorithm:

Loop forever:

- Randomly perturb each parameter up to some amount δ (delta, the “radius”).

- Wait for feedback.

- Estimate the local gradient.

- Update params according to the gradient, scaled by η (eta, “learning rate”).

I think that BlueFin does not decrease delta on each cycle, the way gradient ascent normally would. This means it doesn’t get more precise over time, but also that if the environment is changing, BlueFin is always equally open to learning new info. Or I could’ve misunderstood.

Setting delta and eta seems like a major piece of human guesswork that’s underemphasized in this paper.

The authors say that just measuring the reward in two cycles is enough to get a good estimate of the slope and choose an optimum. This seems to assume that the reward curve is nearly planar? Couldn’t there be curves at least, if not more complex shapes? This is the part of the paper where I have the least expertise, but it feels too simple to me.

The Experiments #

The paper includes three experiments:

- Tune the refresh rate of a workload manager for Exchange Online and SharePoint. This goes into detail about the system we saw in the code example above.

- Tune prewarm and keepalive for FaaS environments. This shows how SelfTune responds to changing circumstances.

- Tune 89 parameters for a Kubernetes-managed network of microservices.

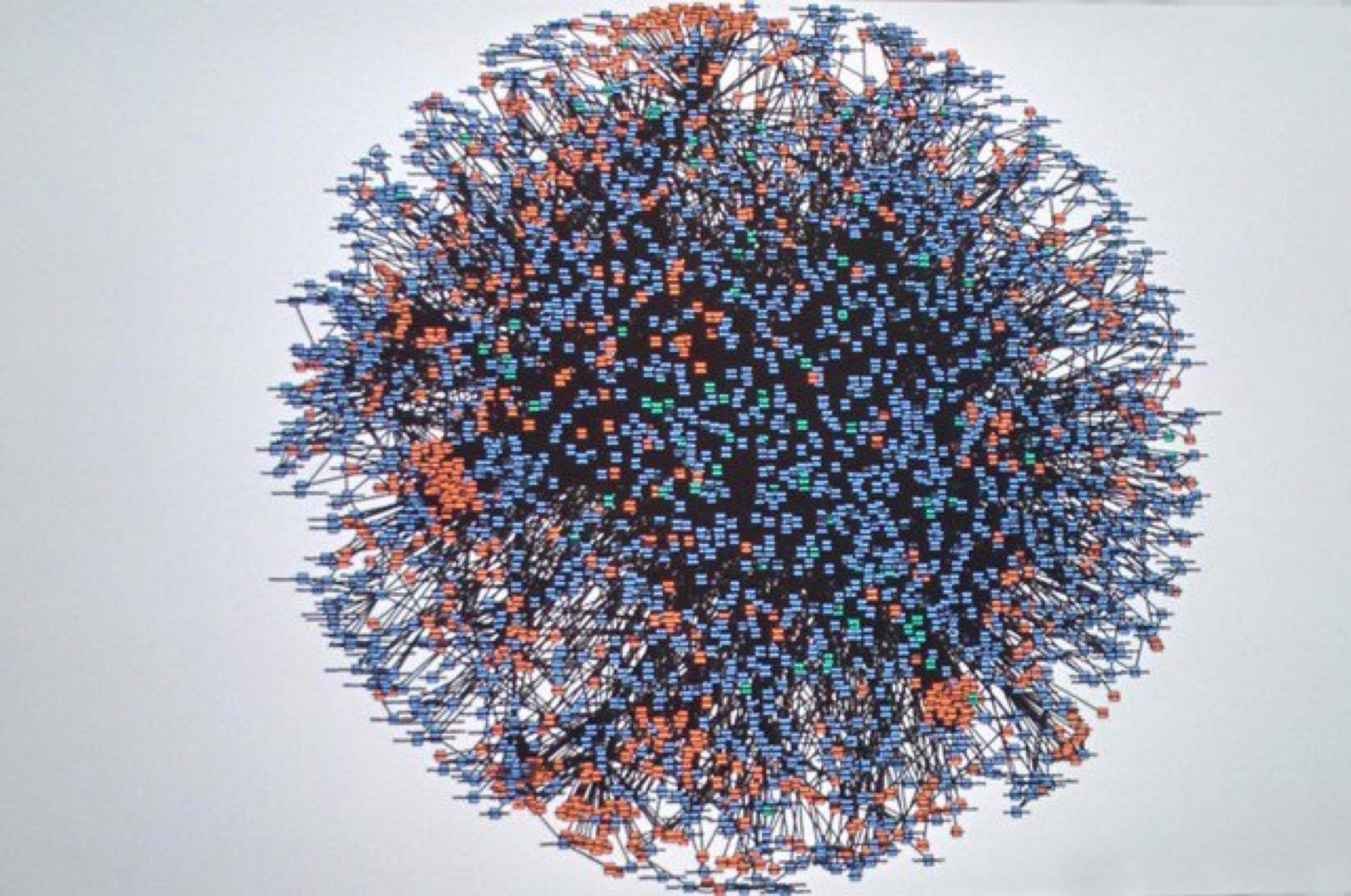

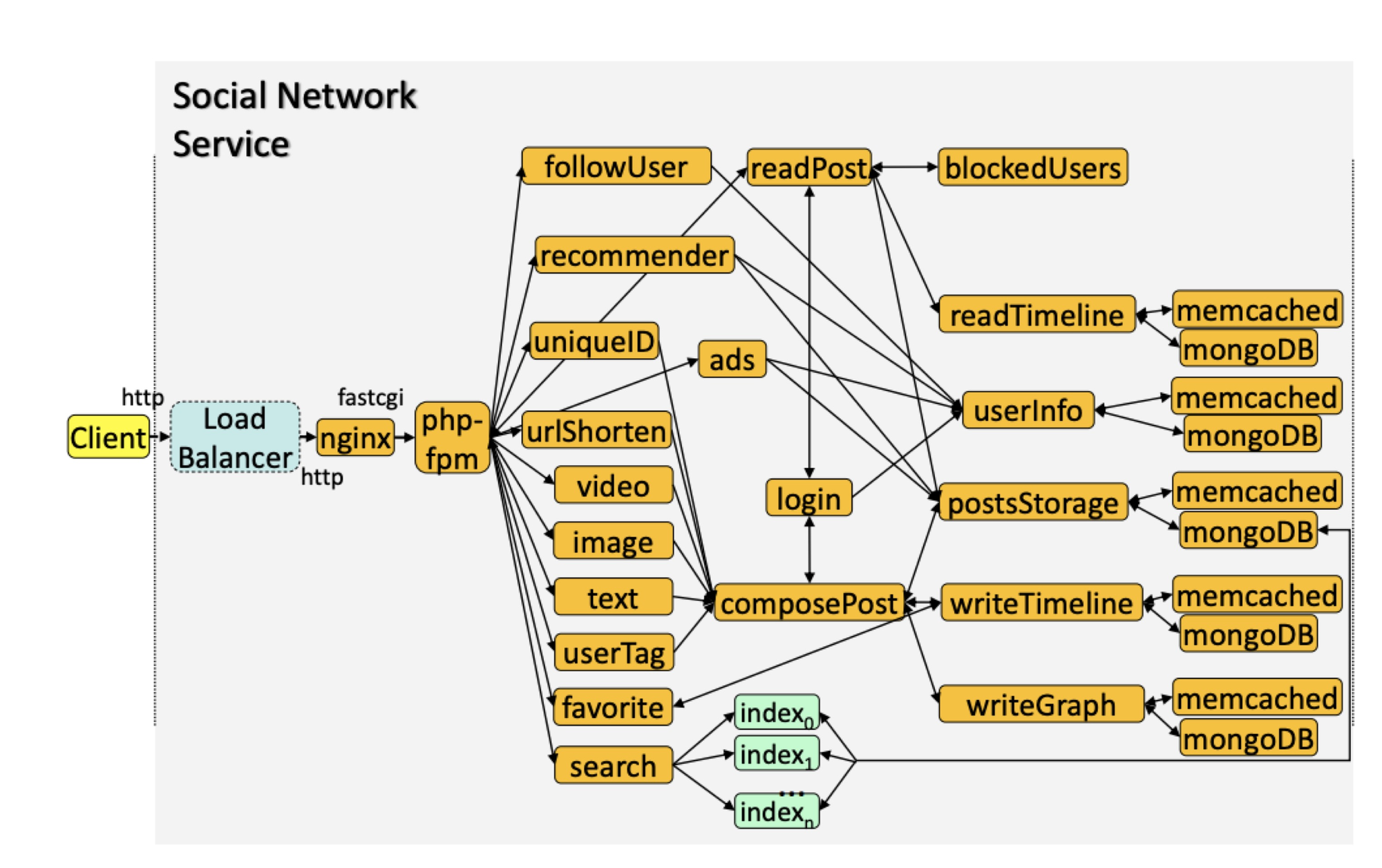

This last experiment is what I really want to see: lots of parameters, lots of interacting microservices. It’s a situation that’s realistic, and unmanageable for humans. The app is a simple social network with 28 microservices, adapted from a research benchmark suite called DeathStarBench. The term “Death Star” refers to these sorts of microservice interaction diagrams:

The AWS microservices "death star" in 2008

The example social network app is much more tractable:

Gan et. al. 2019

Even a small system like this can show complex dynamics and failures. They used the Kubernetes vertical pod autoscaler (VPA) and gave SelfTune control over 4 CPU scaling params plus “about 85” other service-level configs. During the experiment, load came in 15 minute bursts. (The app was completely idle before and after?) The authors compared SelfTune to Bayesian Optimization and two Reinforcement Learning methods. The optimizers themselves don’t scale the system up or down, they tell Kubernetes how quickly to scale up or down. Each method gets 50 rounds, i.e. 50 bursts of 15 minutes. I saw no mention of choosing SelfTune’s hyperparameters δ and η.

SelfTune achieved the best throughput of all methods tested, about 2% better than the next best. The big win was it converged optimally after only 8 cycles, 3-5x faster than alternatives. That matters when you’re learning on live systems—you’re wasting resources or violating SLAs during convergence.

My Evaluation #

I like the emphasis on SelfTune’s API and ease of integration. The experiments seem exceptionally thorough and realistic, compared to similar papers I’ve read.

Humans still have to think and experiment to choose the “radius” and “learning rate” hyperparameters. I wish they had discussed the method for this, it seems important but not automatic. BlueFin is so simple, I wonder whether it risks getting stuck in a suptoptimal local maximum, or conversely whether it risks jumping around forever and missing the maximum. SelfTune’s learning method is pluggable, and I wonder if it would perform better with a more sophisticated method than BlueFin.

I also wondered if real world scenarios are more complex than they tested. Would 8 cycles always find the global optimum, or could you get stuck in a local maximum? And what’s the right scope for each SelfTune instance—per machine, per service, or more centralized? What are the tradeoffs among these deployment styles? The paper seems to advocate decentralization, but I worry about oscillations or shifting bottlenecks when instances interact. A global tuner could help but might also get overwhelmed by complexity. Further research is needed.

Images:

- Unknown photographer, Les Dorizac tuning an upright piano, 1956.

- Norman Rockwell, Piano Tuner, 1947.

- Tuning a Broadwood Cabinet piano, 1842.

- T/4 William Kuehl tunes a Victory Vertical on Guadalcanal.

- Steinway Victory Vertical.