Review: SwiftPaxos: Fast Geo-Replicated State Machines

SwiftPaxos: Fast Geo-Replicated State Machines, in NSDI 2024, proposes a Paxos variant for networks with high latency, and different latencies between different pairs of nodes. Here’s a video of my presentation to the DistSys Reading Group, and a written review of the paper below.

Table Of Contents

Previous Paxi #

Paxos, as you know, is Leslie Lamport’s solution to the problem of consensus among unreliable nodes. The original Paxos achieved consensus on a single value (or “decree”), and it takes 5 one-way network delays in the happy path, counting client-server delays as well as inter-server. The standard analysis of Paxos’s performance assumes that each one-way network delay is the same.

Multi-Paxos #

Multi-Paxos is more practical. It handles the real-world scenario where a group of nodes must agree on a sequence of commands that modify a shared state machine. There’s a long lived leader, and the client sends its request to the leader. The leader broadcasts the client’s command to all the nodes. It commits the command once it hears replies from a majority of nodes, at which point it can execute the command and send the result back to the client. In the happy case, Multi-Paxos takes 4 one-way network delays per value (again counting client-server and inter-server chatter).

Diagram from Wenbing Zhao, “FastPaxos Made Easy”, 2015

FastPaxos #

FastPaxos reduces network delays in the happy case. The client sends its request directly to all nodes at the same time. When the leader hears from three quarters of the nodes, who all agree to put the same command in the same slot, the leader can commit and execute the command and reply to the client. This saves a single, one way network latency, for a total of 3 per value.

Diagram from Wenbing Zhao, “FastPaxos Made Easy”, 2015, plus my scribbles

Why is the “fast quorum” three quarters of the nodes? When I reviewed the Nezha paper a few months ago, I tried hard to understand this, and I think I succeeded. Then I forgot. While I read SwiftPaxos, I tried to remember. I failed. So let’s assume that three quarters is the size of a fast quorum, and that avoids certain problems that a mere majority would cause.

In FastPaxos, different clients are all broadcasting simultaneously to all of the nodes, so there can be conflicts: different nodes can receive different commands, or in different orders. Some of the nodes could tell the leader, “I want command c1 in slot i”, others could say, “I want command c2 in slot i.” The leader resolves a conflict by starting a new round using classic Multi-Paxos. Thus conflicts makes “Fast” Paxos slower than Multi-Paxos.

If you use a geo-distributed deployment with clients in many regions, conflicts are more likely, because their broadcasts reach different nodes with different delays. And in a geo-distributed deployment, restarting consensus after a conflict is very expensive!

SwiftPaxos #

This paper introduces SwiftPaxos. It claims to improve on FastPaxos in the happy case, with only 2 one-way message delays—just from the client to the leader and back! Even in the slow path, there are only 3 one-way delays. I’ll compare all these paxi and describe SwiftPaxos in more detail, and we’ll see if we agree.

Conflict Avoidance #

Sequels to FastPaxos attempt to avoid conflicts with various strategies:

- Egalitarian Paxos (EPaxos) is leaderless. Clients broadcast all commands to all nodes. Each node tracks each command’s dependencies and waits until a strongly-connected component (SCC) of the dependency graph appears. Then all nodes execute commands in the SCC in the same deterministic order, even when some nodes think they observe dependency cycles. The size of the SCCs each node must track, and the delay before a command is executed, can be large (theoretically unbounded).

- Nezha is similar, except it introduces deadline ordered multicast (DOM), which relies on reasonably synchronized clocks. DOM schedules each command to run sometime in the near future, and hopes that on three quarters of the nodes, the same set of commands will arrive before their deadline, so that will reduce conflicts. Nezha also falls back to a slow path when DOM makes a mistake. But Nezha recognizes that different orders are okay among non-conflicting commands (“commuting” commands) because their order doesn’t matter relative to each other.

- SwiftPaxos. Once again, nodes track dependencies among commands. SwiftPaxos never has dependency cycles (stay tuned). Like Nezha, SwiftPaxos ensures all nodes run conflicting commands in the same order, but they can run commuting commands in any order. SwiftPaxos has a low-key leader who’s mostly needed for accelerating the slow path.

What Are Nodes Agreeing To? #

To understand all these systems, I found it helpful to ask what value nodes are agreeing to.

- Paxos, Multi-Paxos: nodes agree that command c is in slot i, so they agree about the total order of commands.

- EPaxos, Nezha, SwiftPaxos: nodes agree that command c has dependencies s.

In EPaxos there’s no consensus on ordering! Only after consensus do the nodes look at the dependency graph that they agreed to, and then resolve cycles and run the commands in the same partial order, where conflicting commands are ordered the same on all nodes. So order is part of the consensus protocol for Paxos and Multi-Paxos, but not for EPaxos. Nezha and SwiftPaxos are similar to EPaxos, but their consensus protocols prevent cycles.

When Can a Node Run a Command? #

- Paxos, Multi-Paxos: as soon as it’s committed.

- EPaxos: after its dependencies (special rules for cycles).

- Nezha, SwiftPaxos: after its dependencies (never any cycles).

In Paxos and Multi-Paxos, as soon as command c is committed, all the commands that c can depend on are already committed, because c is already placed into a total order. In EPaxos, a command can run after the strongly-connected component to which it belongs has been identified, and its dependencies have run. If there’s a cycle, EPaxos breaks it by running the command with the lowest id number first. In EPaxos a command might wait for an unbounded amount of time before it can run: an adversarial workload can blow up the size of these strongly connected graph components. Since Nezha and SwiftPaxos prevent cycles, there’s a bounded delay between nodes agreeing about a command and executing it.

Semi-Strong Leader #

The role of the leader is where SwiftPaxos sharply differs from its predecessors. Every SwiftPaxos quorum must include the leader, but clients can propose commands to any node. The SwiftPaxos leader is sort of first among equals: it’s not as strong as in Multi-Paxos, but stronger than in Egalitarian Paxos (which of course has no leader).

In both Multi-Paxos and SwiftPaxos, there are N nodes with ids 0 through N - 1, the leader of ballot b is the node with id = b mod N, and this leader keeps its job until failure.

As in FastPaxos, SwiftPaxos has slow quorums and fast quorums. In SwiftPaxos, a slow quorum is a majority of replicas, including the leader. This is a departure from other protocols! A majority is not enough to commit a command, the majority must include the leader.

Each fast quorum is either:

- More than ¾ of nodes, including the leader, or

- A specific set of nodes which is a majority including the leader.

You can configure the system to use one kind of fast quorum or the other. The first is more fault-tolerant, the second is faster. Read Section 5.5 where the authors explore the tradeoffs; it’s subtle.

The SwiftPaxos Algorithm #

Let’s talk about the algorithm already. How does it actually work?

First, a client sends command c to all the nodes, the same as in FastPaxos. Each node N does the following:

- Compute c’s dependency set: prior uncommitted conflicting commands. For example, c reads some key x, and node N already knows of an uncommitted command that modifies x, so that uncommitted command is in the dependency set of x.

- Broadcast c’s dependency set to the other nodes.

- Wait for messages agreeing about c’s dependencies from a fast quorum.

- If a fast quorum agrees about c’s dependencies, follow the fast path:

- Wait until all of c’s dependencies are committed.

- Commit c.

- Wait until all of c’s dependencies have executed on N.

- Execute c.

- Otherwise, if no fast quorum agrees about c’s dependencies, follow the slow path:

- The leader proposes its value for c’s dependencies.

- Do normal Multi-Paxos agreement.

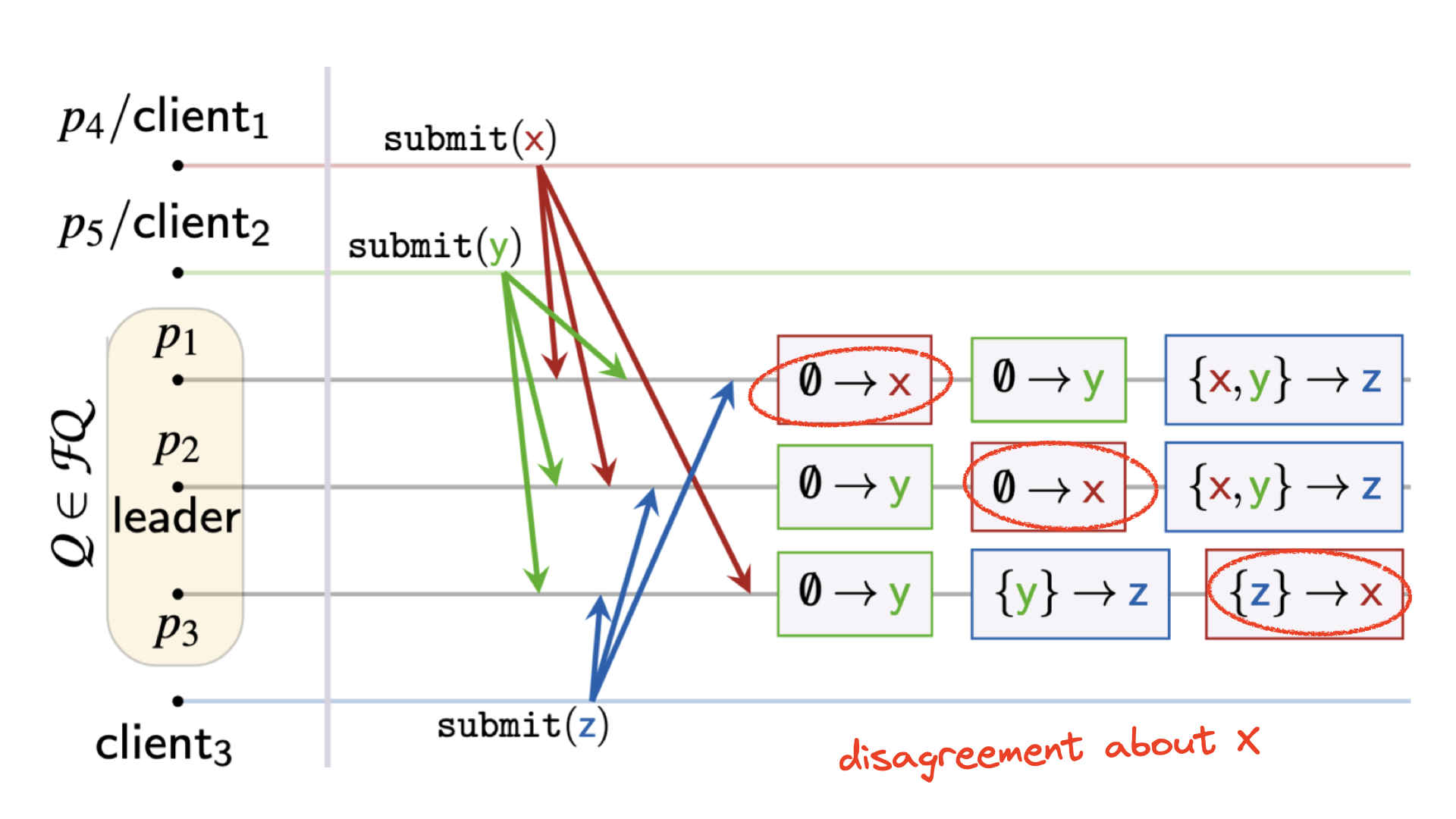

In this figure from the paper, there are three clients. The circled nodes p1-3 are a fast quorum. In this case we’re using SwiftPaxos’s quirky configuration, where the fast quorum is a specific set of nodes that forms a majority and includes the leader.

Figure 1 from the paper.

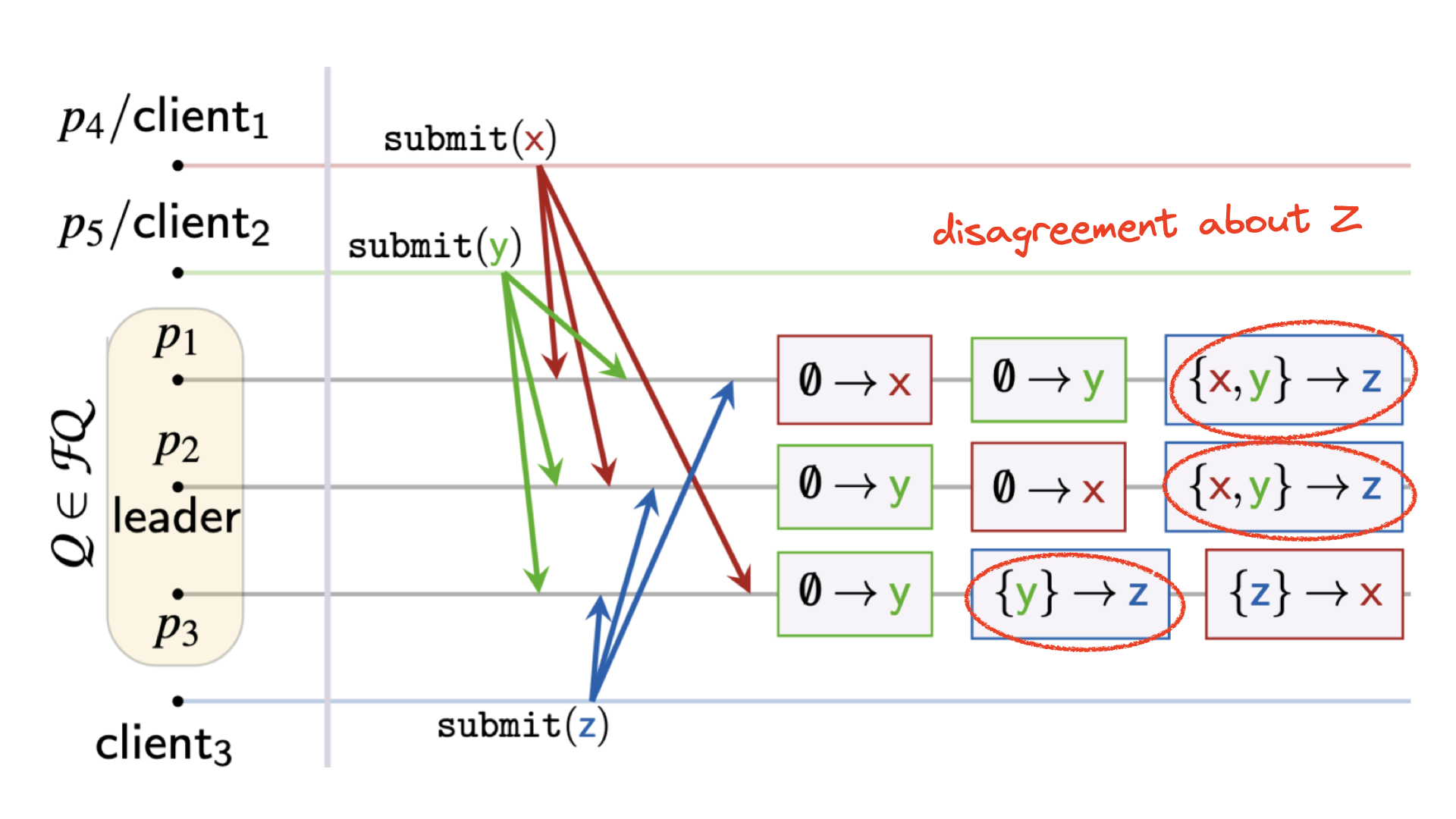

The three clients submit commands y, x, then z, in that order. But due to geo-distribution, the clients have different latencies to different nodes, and each node gets these commands in a different order:

Figure 1 plus my scribbles.

Some of these commands commute and some of them don’t.

All nodes agree about y’s dependencies. Node p1 decided that y does not conflict with x, and so y has an empty set as its dependencies on p1. Nodes p2 and p3 didn’t have to think at all: they had no prior uncommitted commands when y arrived, so they also decided that y’s dependency set is empty.

There is some disagreement about command x. It arrived before the other commands on p1, so its dependency set is empty there. On p2, x arrived after y, but p2 decided it doesn’t conflict, so its dependency set is empty there too. But on p3, x arrived after z, and these commands do conflict, so x depends on z. Thus p3 has a different opinion about x’s dependency set than the other nodes. Since we’ve configured SwiftPaxos with a special fast quorum consisting of these three nodes, any disagreement among them aborts the fast path and forces SwiftPaxos to fall back to the slow path.

Command z has the same outcome: it arrived before conflicting commands on some nodes and after conflicting commands on other nodes, so z has to fall back to the slow path too, i.e. normal Multi-Paxos consensus. A unique feature of SwiftPaxos’s fallback is that a node can vote twice in the same ballot: once for a fast-path proposal and once for a slow-path proposal. Since the leader must be a member of both the fast and the slow quorum, it can ensure only one proposal wins.

Apart from the consensus protocol, there are also optimizations in the client-server protocol. The leader optimistically executes any command immediately, before it’s committed, and sends the result to the client. If the leader and client learn the command was committed they can trust this result. Otherwise, they discard it. This saves some network latency compared to the normal pessimistic execution. On that fast path, a client submits its command to all nodes, receives agreeing replies directly from a fast quorum of nodes, and learns that its command was committed in just 2 one-way delays. The slow path takes only 3.

Why Is This Simpler Than EPaxos? #

SwiftPaxos is simpler than EPaxos, believe it or not. Why? I think it’s because EPaxos commits commands in any order: a command c’s dependencies must all be known, but not necessarily committed yet, before c is committed. That’s how EPaxos ends up with cycles, and why it must build up a certain kind of subgraph (a strongly connected component) before it can start executing commands. SwiftPaxos waits to commit a command until after all of its dependencies are committed. This is why there are no dependency cycles, and why SwiftPaxos doesn’t suffer unbounded delays like EPaxos. (I didn’t understand this until I read the proof in the appendix.)

After a leader change, there’s a recovery protocol in SwiftPaxos which is more complicated than what we’ve seen so far. The recovery protocol does have to deal with cycles. I wonder: if SwiftPaxos used Raft elections, which choose a member from the majority with the longest log, might that prevent cycles during recovery?

Their Evaluation #

The authors have a nifty approach to evaluation. They have sites scattered around the earth. Eight sites run clients, 3 sites run a server each, and 2 sites run both clients and a server. At the best client site, in the middle row of the chart, clients are near the nodes, and at the worst site at the bottom clients are far from them, so we can see the effect of getting a fast quorum agreement more or less often. The top row shows the average across all client sites. They compare how various protocols perform given different geo-locality and different rates of conflicts among commands.

SwiftPaxos permits two ways of defining a fast quorum, and for this experiment they choose the second option: a specific set of nodes, a majority including the leader, constitute the only fast quorum.

Figure 7a from the paper.

The y axis is each protocol’s latency speedup relative to Paxos, and the x axis is how often commands conflict. SwiftPaxos is the gold line. SwiftPaxos almost always beats the other protocols, of course, because this is the SwiftPaxos paper. But notice how some of the other protocols, particularly CURP+, are a little better at low conflict rates at the worst site. I don’t know the CURP+ protocol, so I don’t know why it’s better in this scenario.

Figure 7b from the paper.

Here’s the same average, best, and worst sites, evaluated by the cumulative distribution function of latency. The conflict rate is fixed at 2%. Again, SwiftPaxos beats all the others at the best site and the average site. But a couple of the other protocols are actually better, at this 2% conflict rate, at the worst site where the client is very far from a fast quorum.

My Evaluation #

The paper is well-written, but the protocol is complex and hard for me to understand, probably because I don’t know EPaxos well. I had to read the appendix to understand why it avoids dependency cycles, unlike EPaxos.

I’ve heard people say EPaxos is impractical, mainly because of the unbounded execution delay and accumulation of state at the nodes. EPaxos is interesting research and often cited, but not actually used. Perhaps SwiftPaxos is the practical sequel to EPaxos? It’s a new paper, we’ll have to see how the community responds and builds upon it. The savings in one-way network delays seems significant.

Audubon, the American swift.