Review: Nezha: Deployable and High-Performance Consensus Using Synchronized Clocks

This is a review of Nezha: Deployable and High-Performance Consensus Using Synchronized Clocks, from NYU and Stanford researchers last year. To understand this paper I had to relearn how quorums work in Paxos and Fast Paxos, so we’ll start there.

Table Of Contents

Classic Paxos Quorums #

In Paxos there are proposers, acceptors, and learners. Each server usually plays all three roles, but the protocol’s often described as if the roles are separate (confusingly, in my opinion). The protocol is like:

- A client sends value v to a proposer.

- The proposer sends “prepare” to the acceptors, with a unique current round number.

- The proposer hears “promise” replies from a majority of acceptors.

- The proposer knows that only it can propose a value for this round.

- The proposer sends “accept” to the acceptors with the value v for this round.

- A learner hears “learn” messages from a majority of acceptors, it knows v is the value for this round.

- The learner sends an acknowledgment to the client.

Real systems use MultiPaxos, in which the “prepare”/“promise” exchange is done once to establish a “distinguished proposer”, which then drives a series of “accept”/“learn” exchanges indefinitely. Optimized MultiPaxos is nearly the same as Raft, it’s just explained much worse.

Fast Paxos Quorums #

- Before any proposals, a proposer sends “accept any” to the acceptors with no value for this round.

- The proposer hears “promise” replies from a majority of acceptors.

- Fast track: the client sends value v directly to the acceptors!

- A learner hears “learn” messages from 3/4 of the acceptors, with the same value.

- The learner sends an acknowledgment to the client.

Fast Paxos saves a single one-way message delay compared to regular Paxos. But it risks collisions: several clients can send several values to the acceptors in the same round. Fast Paxos uses a larger “fast quorum” size to check for collisions. If no value is chosen by a fast quorum, the system goes into a slow error-recovery mode. Fast Paxos is safe—it will never accept multiple values in a round—but its performance is brittle; it’s slow under contention.

Quorum Sizes #

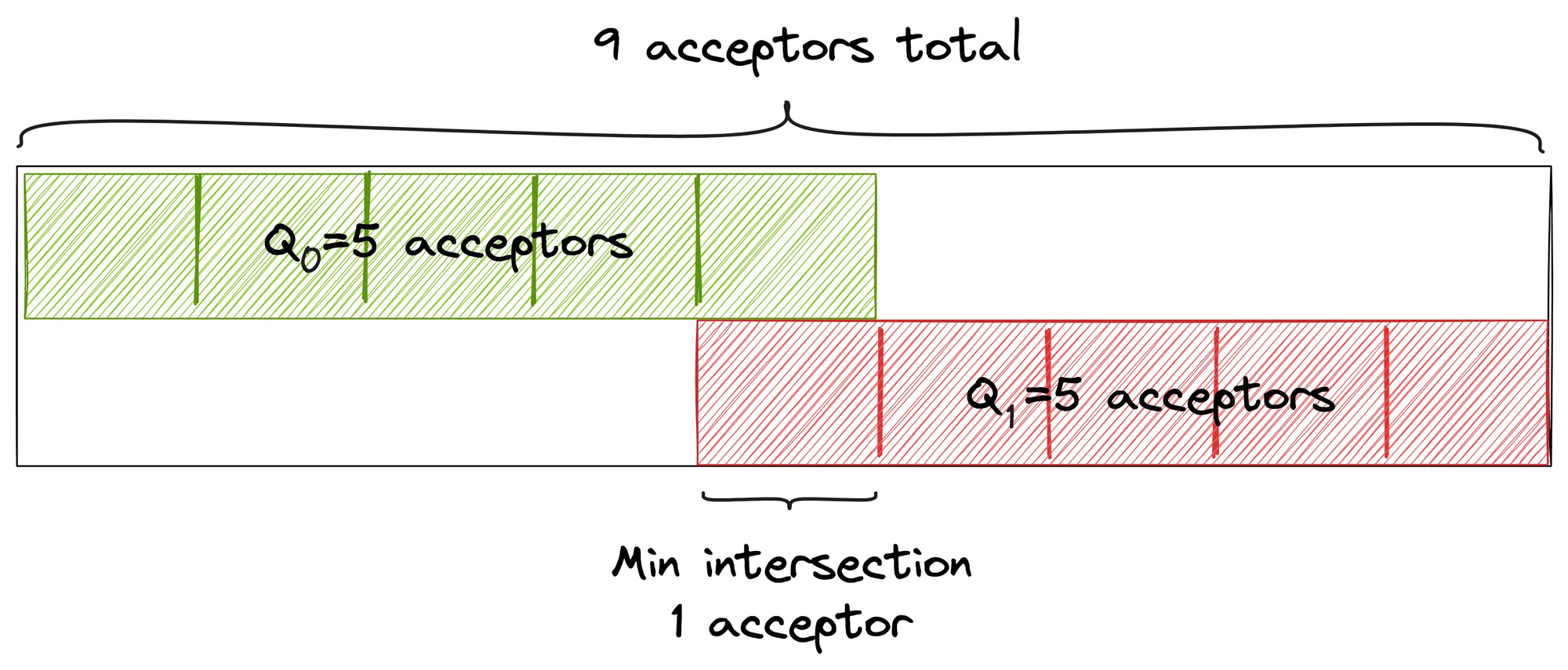

A classic Paxos quorum must be a majority, so that any two quorums Q0 and Q1 share at least one node. For example with 9 acceptors, a quorum is at least 5:

Thus if a minority of acceptors fails, at least one survivor remembers accepting v. (If a majority of acceptors fails, the system won’t accept more values.)

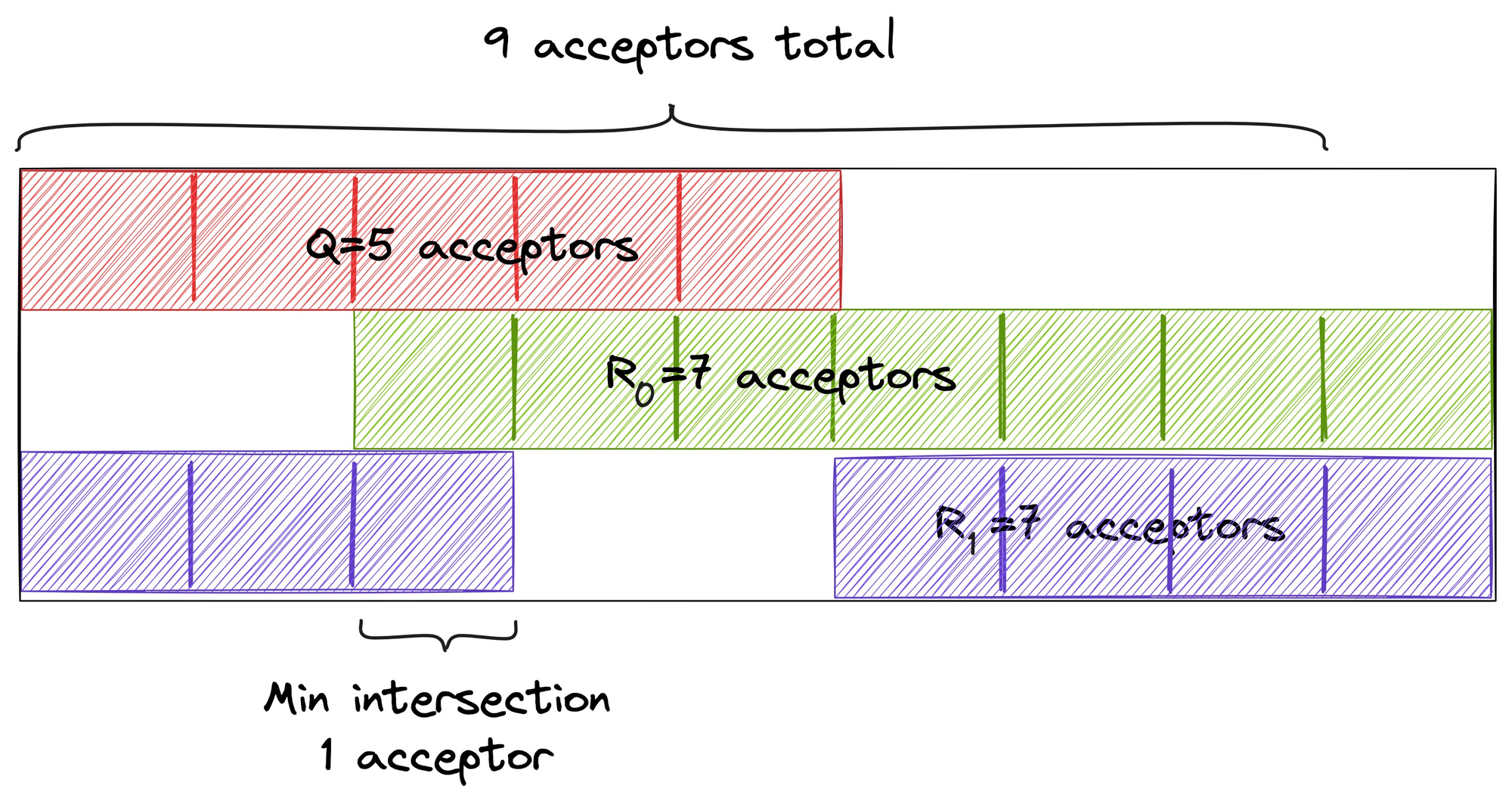

The rule for fast quorums is, any classic quorum Q must share at least one node with any two fast quorums R0 and R1. With 9 acceptors, a classic quorum is at least 5 as before, and a fast quorum is at least 7:

If a fast quorum accepts v and then a minority of acceptors fails, at least one survivor remembers v, and no other value could’ve been accepted by a fast or classic quorum. In classic Paxos, “no other value” is guaranteed by the “prepare” phase, where one proposer hears a majority promise to stop accepting other proposers’ values with earlier round numbers. But in Fast Paxos all the failed acceptors could’ve accepted some other value. We need a bigger fast quorum to know that we’ve chosen a unique fault-tolerant value.

There are various quorum sizes that satisfy this property, and there are tradeoffs when you choose a quorum size. See Lamport’s Fast Paxos paper for details.

Nezha #

Now I can describe the Nezha paper. As author Jinkun Geng mentions in a podcast interview, Nezha is a Chinese diety with three heads and six arms, “so he has wonderful fault-tolerance.”

Nezha bridges the gap between protocols such as MultiPaxos and Raft, which can be readily deployed, and protocols such as NOPaxos and Speculative Paxos, that provide better performance, but require access to technologies such as programmable switches and in-network prioritization, which cloud tenants do not have.

So the authors’ motivation is to make a high-performance consensus protocol that can be deployed by cloud customers in public clouds, without requiring special access to the hardware. Nezha improves performance using tightly-synchronized clocks, which increasingly are available to cloud tenants, especially on AWS.

Nezha is like Fast Paxos plus Deadline-Ordered Multicast, speculative execution, and a stateless proxy.

Deadline-Ordered Multicast (DOM) #

Just like Fast Paxos, Nezha has a fast path and a slow path, and it’s crucial to take the fast path as often as possible. The authors say that message reordering is the most common reason for taking the slow path: a sequence of messages from the proxy take different network paths to the same server and arrive out of order. DOM reduces reordering thus:

- The sender attaches a deadline to each message: the sender’s clock time + one-way-latency estimate.

- The receiver rejects any message received after its deadline.

- The receiver executes each message after its deadline passes (according to the receiver’s clock).

- The receiver executes messages in deadline order.

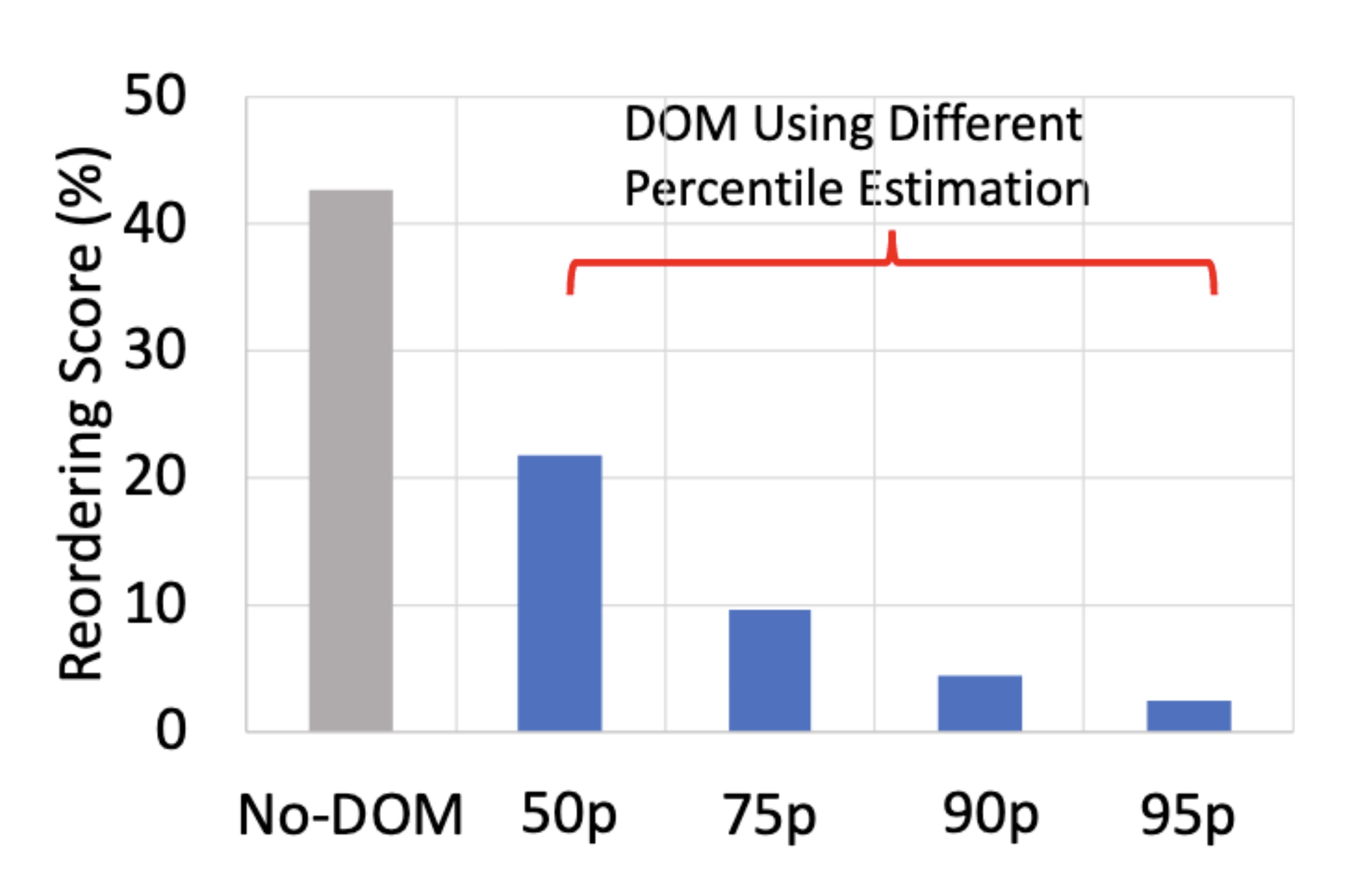

The authors evaluate DOM in Google Cloud:

The reordering score is the percent of messages in a sequence that are not in the longest ordered subsequence. E.g., if there are 100 messages and the longest ordered subsequence is 80 messages long, the reordering score is 20. Higher is worse. Without DOM, they found in Google’s cloud, under high contention, that the reordering score was over 40%.

DOM estimates the distribution of one-way latencies, using a technique called Huygens from another paper. Once it knows the distribution of one-way latencies, it knows the 50th-percentile one-way latency, the 75th, and so on. So the “50p” bar in the chart above means the authors configured DOM to set a deadline that was the sender’s clock plus the 50th-percentile one-way-latency. A longer delay further reduces reordering, but the receiver waits longer on average before executing each message. So the delay is a tunable parameter; there are tradeoffs and some optimum that you have to find.

I was surprised to read that the Nezha authors choose the 50th percentile. This means half of messages arrive after their deadlines! However, not all late messages force Nezha to take the slow path, only messages that are late and out of order. If a sequence of messages are all late, they can still be ordered. As the chart indicates, configuring DOM so that half of messages are late reduces the reordering score to barely 20%.

Speculative Execution #

In regular Paxos, servers don’t execute a client’s command (they don’t update their state machines) until they know the command has been logged by a quorum. But the Nezha leader executes and acknowledges a command as soon as its deadline passes. The client accepts the execution result once it hears confirmation from a fast quorum. This reduces latency. If the leader is deposed before committing the command, the client rejects the result and retries the command.

Stateless Proxy #

Nezha includes a proxy that encapsulates some Nezha logic. The proxy runs the Huygens protocol to estimate one-way latency and to tightly synchronize its clock with the other proxies and the servers. The proxy is basically stateless and horizontally scalable; it isn’t responsible for any ordering guarantees. Smart proxies permit dumb clients.

The Nezha Protocol #

Fast Path #

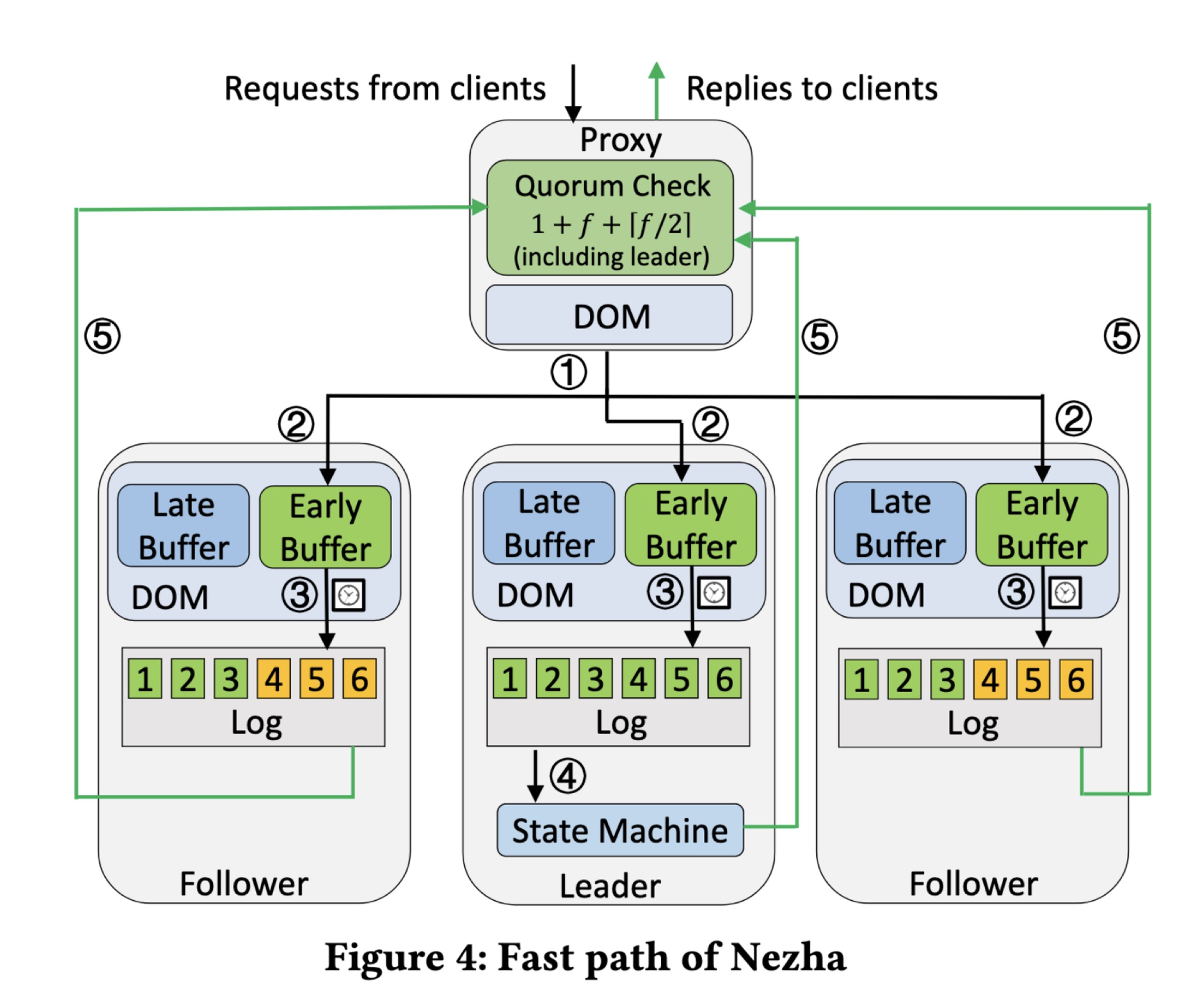

First a request comes from a client.

- The proxy assigns a deadline from the proxy’s reasonably-synchronized clock, plus a delay that’s a percentile of the one-way-latency estimate. The proxy sends the message to all the servers.

- The leader and followers get the message, and if its deadline hasn’t passed, the message goes in their “early” buffers to wait. This is the fast path, if the message is late we take the slow path, which I’ll describe later.

- Soon after the deadline, each server removes the message from the early buffer and logs it. Servers process messages in deadline order.

- The leader executes the command…

- …and returns the result to the proxy. The followers send acknowledgments to the proxy without any result, because they don’t have state machines and they don’t execute commands, they only have logs. (So how can a follower become a leader? Read the paper.)

Each acknowledgment includes a hash of the whole log, so the proxy knows whether all the servers in the quorum have the same log. We know the messages are ordered correctly by timestamp, but some servers could be missing messages.

If the proxy hears a fast quorum of replies with the same hash, including from the leader, it accepts the result. It knows it’s durable.

So that’s the fast path. It saves some latency, because the proxy sends the message to all servers at once, and all servers respond directly to the proxy, instead of routing messages through the leader like in MultiPaxos or Raft. It might incur some latency though, if you find that you have to configure the DOM delay to a high percentile.

What about the slow path? Let’s look especially at messages that arrive too late.

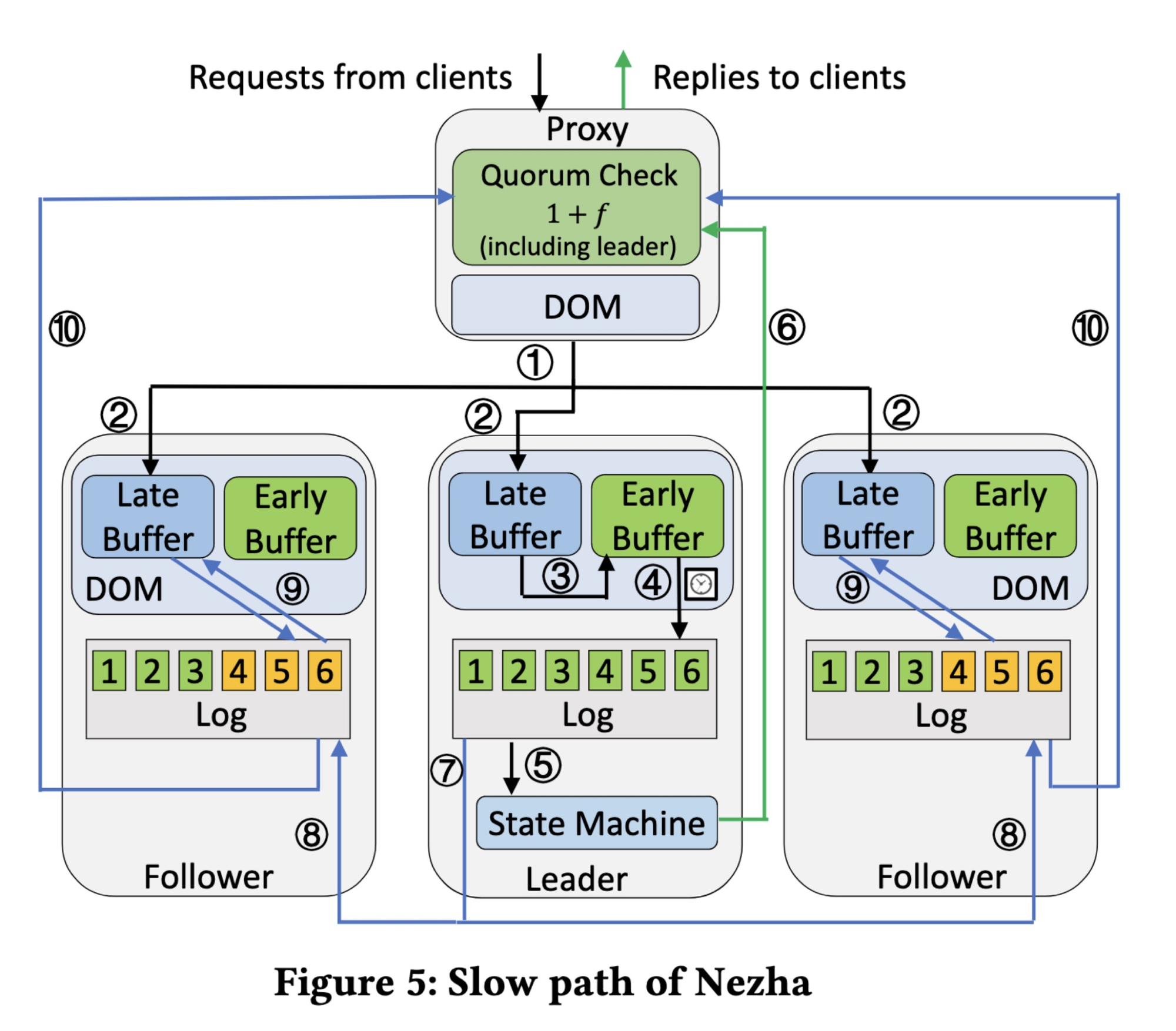

Slow Path #

A request comes from a client again.

- The proxy assigns a deadline and sends it to the servers, the same as before.

- This time the message arrives late and goes to the late buffer.

- The leader eventually modifies the message’s deadline, from a past time to a future time, and puts it in the early buffer!

- Once the new deadline passes, the leader logs…

- …and executes the message…

- … and sends the result to the proxy.

- Concurrently, the leader also sends the message’s ID and its new deadline…

- …to the followers. Note how this is slower than the fast path: it requires leader-follower communication, unlike the fast path.

- Luckily the followers don’t need the whole message, they have it in their late buffers, so they just retrieve it from there and log it in the proper position with its new deadline. If a follower didn’t receive the message at all, then it has to fetch it from another server, which is even slower.

- Finally the followers acknowledge the message…

- …and the proxy hears from a majority (a slow quorum) of servers, all with the same hash, and accepts the result.

The authors claim that the slow path is still faster than some competing protocols like MultiPaxos, because of speculative execution at the leader. They say the slow path is only one message delay slower than the fast path.

Of course, a message could arrive before its deadline on some servers, and late on other servers. There are worse cases, if messages are dropped between the proxy and the servers, or between the leader and the followers, or if a replica fails and rejoins, or there’s a new leader. The paper handles these scenarios and I will not.

I’ll summarize everything so far: Typical consensus protocols route through the leader to guarantee ordering, but this costs some network hops and makes the leader a bottleneck. Nezha uses Deadline-Ordered Multicast and large quorums to guarantee ordering, so it can parallelize more.

Commutativity Optimization #

Messages are commutative if they contain commands operating on different keys. Nezha relaxes the rule for a message to enter the early buffer.

- Naïve rule: the message’s deadline must be after the last message released from the early buffer.

- Optimized rule: its deadline must be after the last non-commutative released message.

I see how this preserves per-key linearizability, but I think it violates whole-database linearizability, also known as strict serializability. That’s ok, I believe Nezha only promises per-key linearizability, and it’s the right choice for many users.

Their Evaluation #

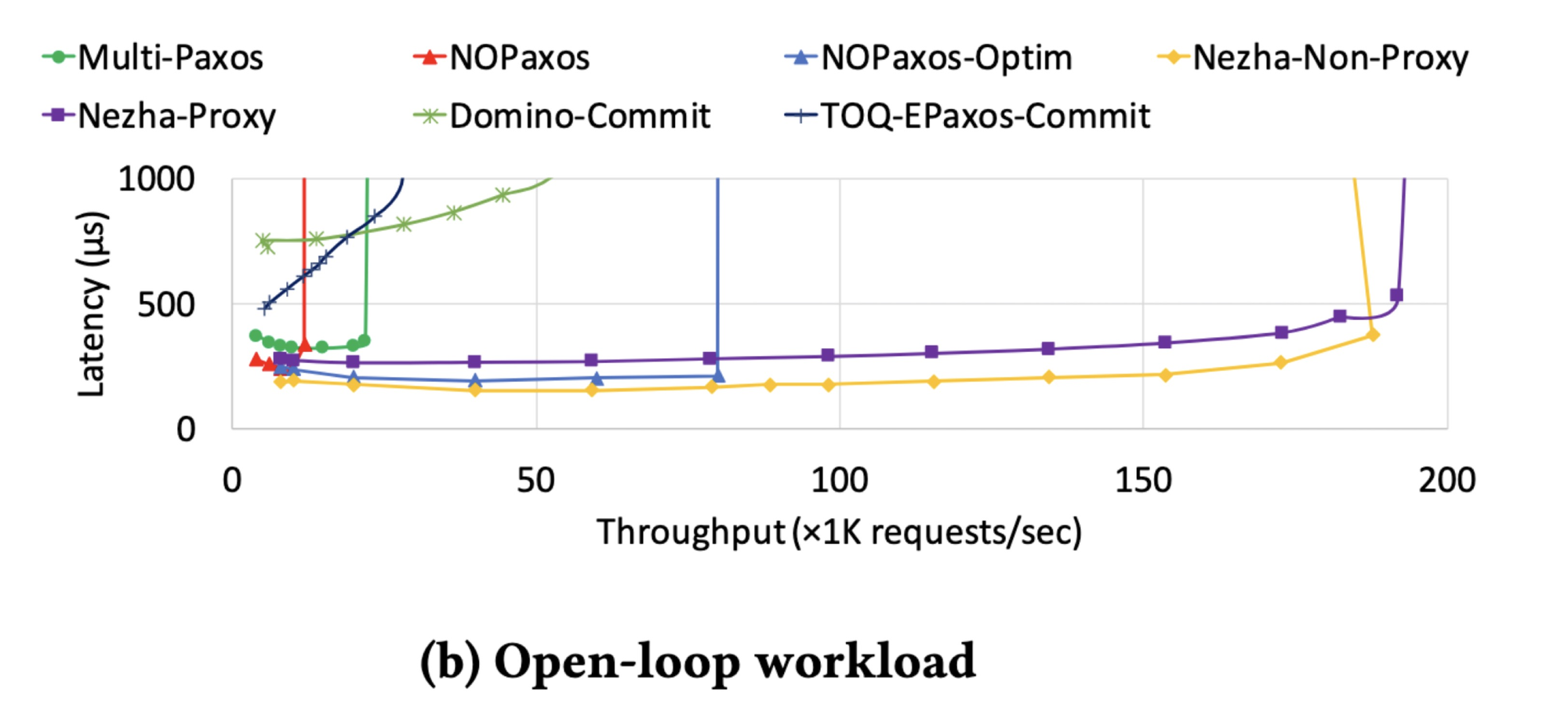

The authors ran experiments in Google Cloud with various configurations. I’ll concentrate on the open-loop workload with 3 replicas, 5 proxies, and 10 clients. The Huygens clock sync protocol is installed on the proxies and servers, it gets a p99 clock error of only 50 ns! They use a minimal application that processes messages with no command logic. They have Poisson arrivals, 50% reads/writes, and a somewhat skewed access pattern with some hot keys and some cold ones.

As expected, Nezha outperforms everything, because this is a paper about Nezha. But this is an even more dramatic chart than usual in evaluation sections.

NOPaxos (“Network-Order Paxos”) might be at a disadvantage here, because NOPaxos wants low-level access to the network and they don’t have it in Google’s public cloud. The Nezha authors say “we use the implementation from the NOPaxos repository with necessary modification: we change switch multicast into multiple unicasts because switch multicast is unavailable in cloud. We use a software sequencer with multi-threading for NOPaxos because tenant-programmable switches are not yet available in cloud.” NOPaxos-Optim is their enhancement of the published NOPaxos code; they relieved a bottleneck with multithreading. The authors also wrote a technical report with more benchmarks; NOPaxos-Optim outperforms Nezha in one test there.

To measure latency, we use median latency because it is more robust to heavy tails. We attempted to measure tail latency at the 99th and 99.9th percentile. But we find it hard to reliably measure these tails because tail latencies within a cloud zone can exceed a millisecond.

I want to see Nezha’s tail latency, and I don’t understand this explanation for omitting it. Cloud network latencies are indeed unpredictable, which is a big risk for a protocol like Nezha, which is optimistic and explicitly designed for public clouds. The authors’ justification sounds to me like, “This problem is so bad we decided to ignore it.”

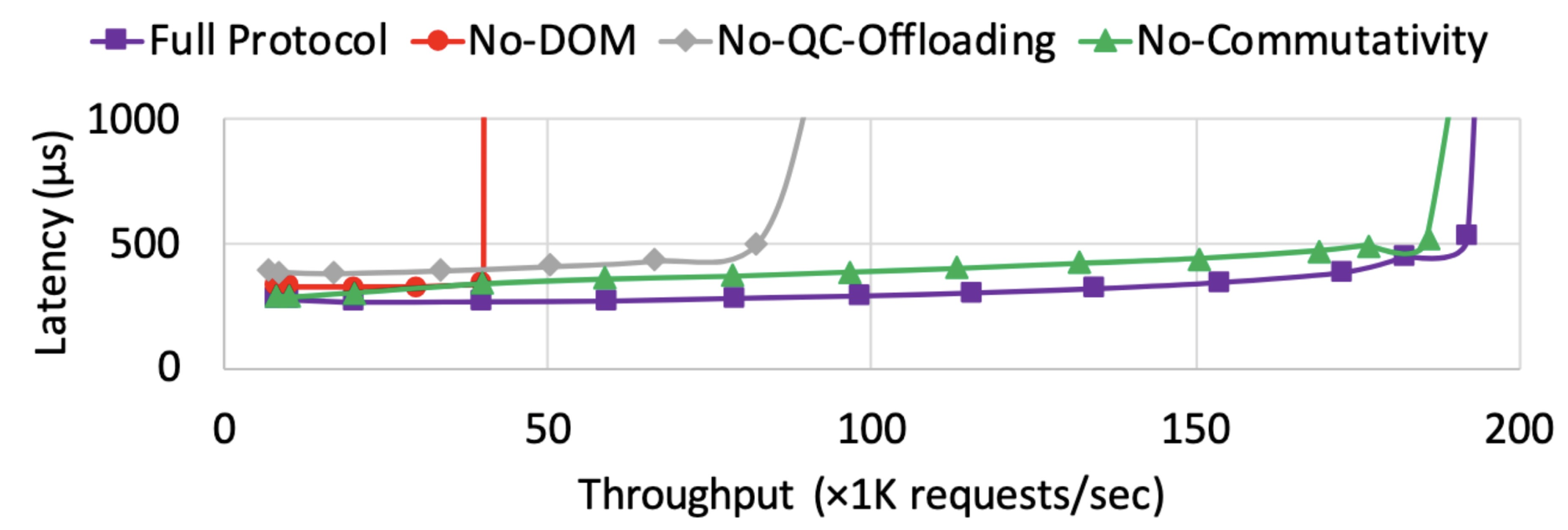

The paper includes an “ablation study”, a neat bit of jargon for studying the effects of removing optimizations individually.

Deadline-Ordered Multicast is obviously important. Without it (red line), Nezha is practically the same protocol as MultiPaxos and performs about the same: it’s usually on the slow path due to message reordering. “Quorum-Check Offloading” to the proxy or client is important, because it removes some work from the leader, which is otherwise a bottleneck (gray). It seems that the leader’s CPU is saturated and quorum-checking contributes to that. Commutativity is apparently not important for throughput and it only slightly improves latency (purple vs. green). Perhaps that’s because DOM is so good at message ordering that commutativity doesn’t help much, or perhaps it’s because their workload skewness means many messages are non-commutative?

My Evaluation #

- The paper is written for users like me and MongoDB Atlas: public cloud users without special hardware or network access. I appreciate this focus.

- I worry about performance variability in an optimistic protocol with fast and slow paths. How much does Nezha suffer when there’s contention and/or clock skew?

- The authors write, “Nezha does not assume the existence of a worst-case clock error bound”, but that’s just for safety. Performance does rely on tightly synchronized clocks. Ever since Metastable Failures in Distributed Systems, I dislike optimizations that work sometimes. Therefore I wish they’d benchmarked tail latency, not just median latency, and tested more adverse conditions like workload skewness, clock skew, and network latency variability.

- Deadline-Ordered Multicast is slick, and useful. If it’s tuned, it should be nearly free. But how does DOM fare when latencies to different nodes differ?

- The commutativity optimization is clever, although its usefulness is overshadowed by DOM here.

- Some of my colleagues were annoyed that the Nezha authors don’t credit the Tempo paper and other precedents.

- Synced clocks in public clouds are real now. We can use them in distributed protocols. This is a superb example.

I learned a lot from this paper, especially since I presented it to the DistSys Reading Group and wrote this review. I want to see more of this kind of research: the use of public cloud features for distributed protocols.

Further Reading #

- The Huygens paper: Exploiting a Natural Network Effect for Scalable, Finegrained Clock Synchronization. It’s cool, it uses machine learning to estimate minimum one-way latency and hence clock skew. Recommended. Unfortunately the implementation is closed-source (its authors have a startup), but see the Quartz paper.

- The Nezha technical report (more benchmarks).

- Podcast interview with author Jinkun Geng.

- Code, including TLA+ specification.

- Murat Demirbas’s summary.

Nezha images are from Nezha Conquers the Dragon King.