Multi-Paxos in Python, tested with Jepsen

I want to understand Paxos better, especially Multi-Paxos, so I implemented it (badly) in Python. I tested it with Jepsen—it was a chance to play with Jepsen, and a way to check if I’d understood Paxos well enough to code it. I spent about two weeks on the project (one was MongoDB’s periodic “Skunkworks” week). Here’s a rambling report on my experience.

Paxos #

Paxos is reputed to be hard to understand, and it lives up to its reputation. As I covered in my review of the “Paxos vs. Raft” paper, the original Paxos description is obfuscated, and each subsequent clarification uses different jargon to describe a different variation of the algorithm. As Howard et. al. explain in that paper, once you implement Multi-Paxos with all the modern enhancements, it’s almost Raft. I could have accepted that on faith and implemented Raft, but I wanted to work the problem myself and understand Paxos on its own terms.

I skipped Leslie Lamport’s original “Part-Time Parliament” paper and went straight to his “Paxos Made Simple”. It really does make Paxos simpler—Lamport’s a terrific writer, aside from going overboard in “Part-Time Parliament”—but the paper explains single-decree Paxos and I want to understand Multi-Paxos, the minimum enhancement that makes Paxos practical. Next I read “Paxos Made Moderately Complex” by Renesse and Altinbuken. It’s sandbagged; they should have called it “Monstrously Convoluted”. They take the three roles of “Paxos Made Simple” (Proposer, Acceptor, Learner) and add Replica, Leader (same as Proposer?), Commander, and Scout!

I think the proliferation of roles is yet another reason why Paxos is harder to understand than Raft, and an underappreciated one. In Raft, there is one permanent role, Server, and it performs one of two temporary roles: Leader or Follower. But in “Paxos Made Simple” there are three permanent roles, and the Proposer can assume the temporary role of “Distinguished Proposer” (like a Raft Leader). In “Moderately Complex” there are about six permanent roles. Roles aren’t actually distinct machines or processes, they could be implemented as threads on one server. The point is to decompose Paxos into small, single-threaded subroutines. But this decomposition moves the complexity from the roles to their interactions, and makes it harder for me to envision a Paxos implementation in code.

Anyway, I found what I sought in an unlikely place: “Formal Verification of Multi-Paxos for Distributed Consensus” by Chand, Liu, and Stoller. It’s Multi-Paxos, described unambiguously in TLA+. The authors only specify the Proposer and Acceptor roles, so I took the Learner pseudocode from “Moderately Complex”, along with some optimizations, and coded up a working Paxos in Python.

I’m grateful to the authors of all these papers. “Made Simple” is a good start, “Formal Verification” was my primary reference, and “Moderately Complex” has a ton of detailed explanation, plus pseudocode and Python for every role. Together they gave me enough hints to hack together an implementation in under a week.

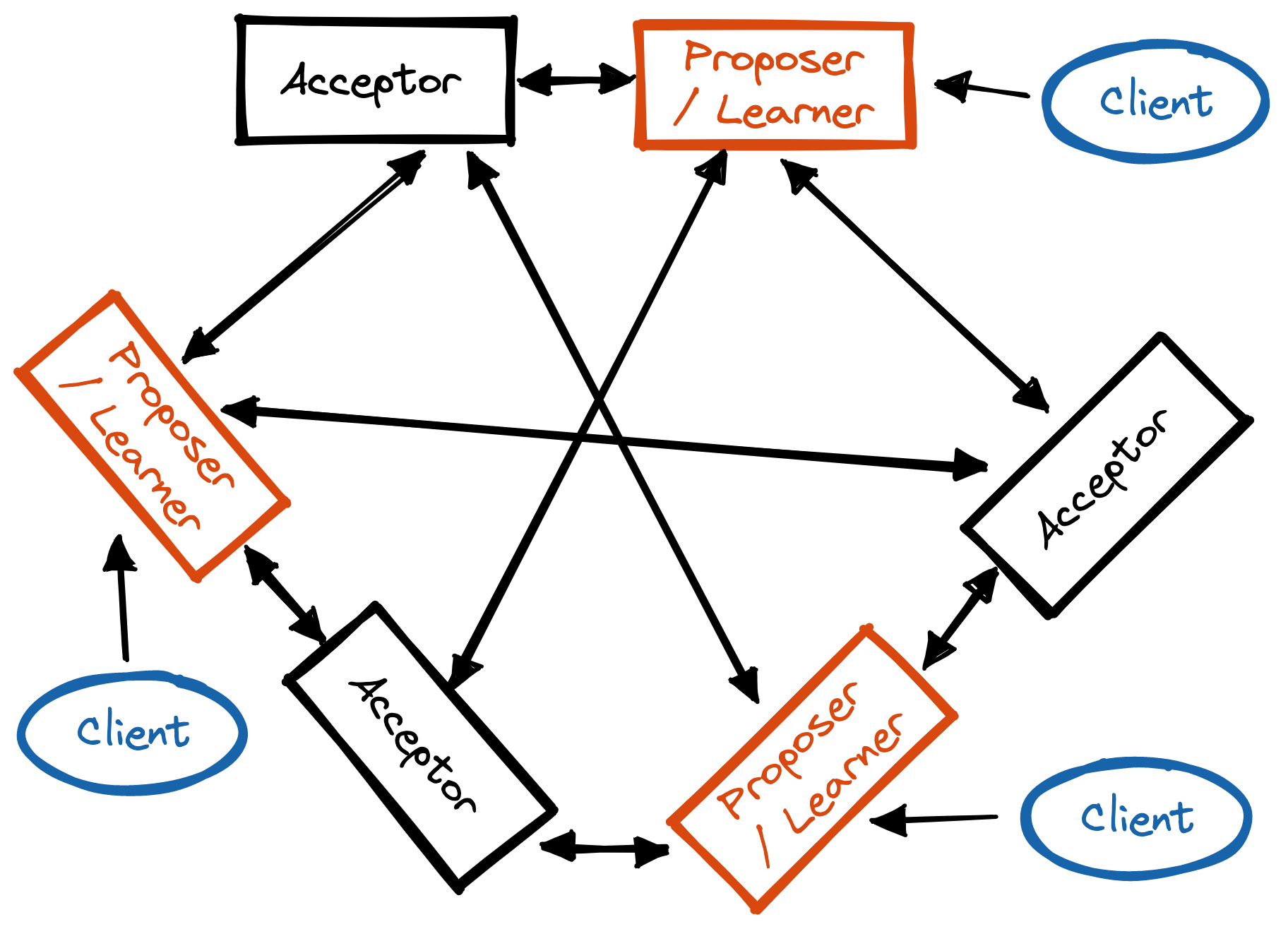

I used the Requests library to send messages and Flask to receive them. I combined the Proposer and Learner roles into one Python class and implemented the Acceptor in a separate class. Each class has a queue of incoming messages that it processes one at a time, which excused me from any mutex chores. I also wrote a client in Python, which sends its request to any Proposer the user chooses.

My Multi-Paxos has no reconfiguration protocol. It has no stable leader, thus no election protocol and no Fast Paxos. What it lacks in features it makes up for in bugs. It can’t run very long since it uses more memory and passes larger messages with each operation. Any server can propose a value at any time, which leads to conflicts. If a client submits a value, the chosen Proposer will keep proposing it with a higher ballot and slot until it’s accepted, even after the client times out. In high-concurrency tests a value may be stuck in a conflict-retry loop for minutes. This would be bad for a production system, but good for my purposes, since conflicts are the most interesting event I want to test.

The purpose of Multi-Paxos is for the servers to agree on a sequence of operations on a replicated

state machine (“RSM”). I could’ve chosen any data structure as their shared state, so I chose an

append-only list of integers. A client can send “1” to a Proposer, and another client can send “2”,

and eventually the servers may agree that the RSM’s state is [1, 2]. The server replies to each

client with the current list. I knew

from the Elle paper that an append-only list is

an easy data structure to check for linearizability. Which leads us to the second half of this

project….

Jepsen #

I’ve been curious about Jepsen ever since Kyle Kingsbury (aka “Aphyr”) appeared with his consistency checker and ruined every distributed system implementer’s life. It’s found a few bugs in MongoDB (my day job) and in dozens of other systems.

I followed the terrific Jepsen tutorial and got it set up on a four-node EC2 cluster, then spent a week building a basic Jepsen test for my Paxos code. Jepsen is a test framework written in Clojure; you have to subclass its components and write some custom functions. I don’t know Clojure, so I used Kingsbury’s Clojure From The Ground Up, which got me started after an encouraging introduction:

I want to help in my little corner of the technical community—functional programming and distributed systems—by making high-quality educational resources available for free…. As technical authors, we often assume that our readers are white, that our readers are straight, that our readers are traditionally male. This is the invisible default in US culture, and it’s especially true in tech. People continue to assume on the basis of my software and writing that I’m straight, because well hey, it’s a statistically reasonable assumption. But I’m not straight.

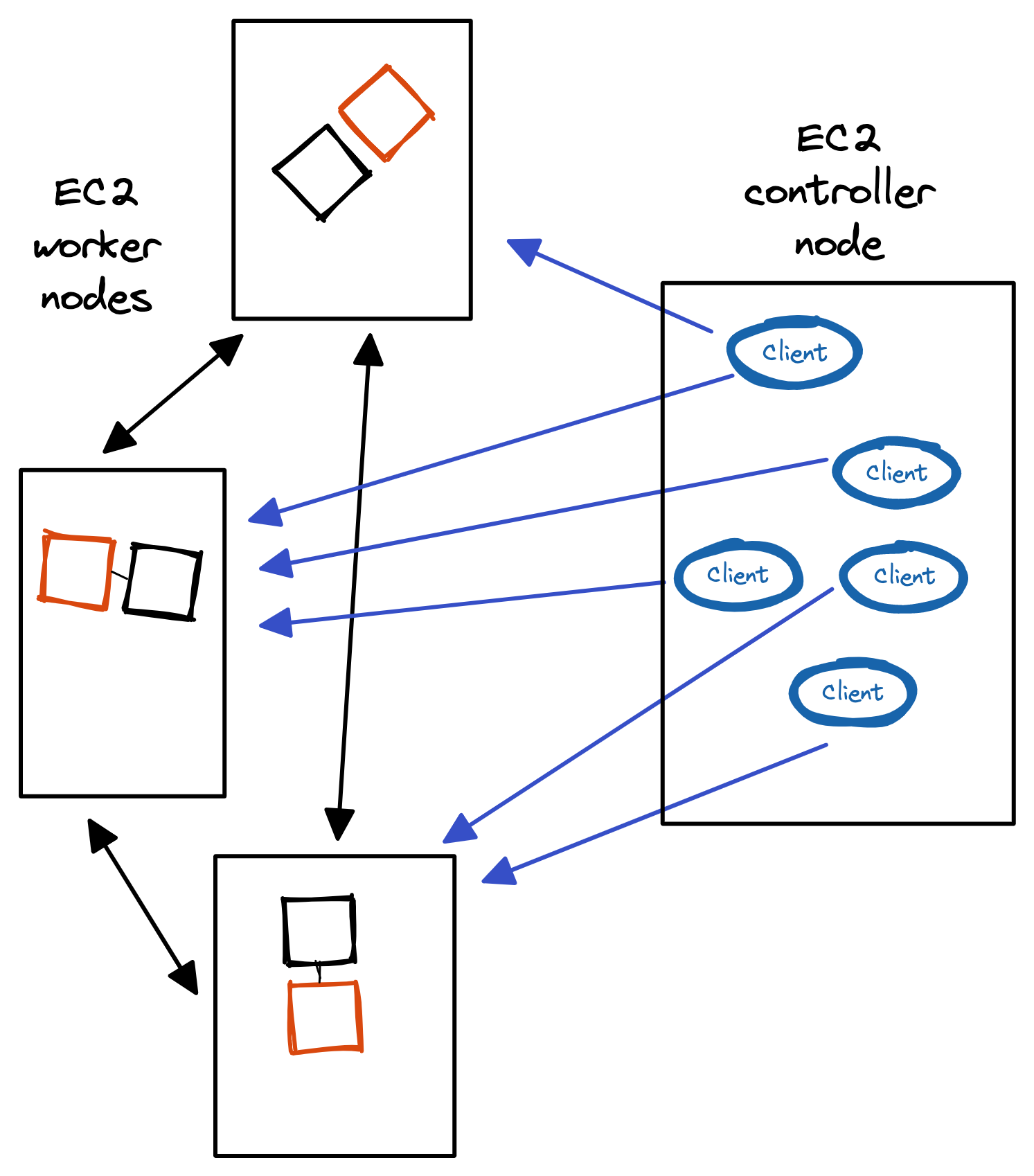

This softened my irritation about an obscure language barring my way. Kingsbury didn’t mean it to be a barrier. Anyway, between my undergraduate memory of Scheme, Kingsbury’s guide, and Stack Overflow, I didn’t lose too many hours to Clojure syntax. I set up a four-node EC2 cluster, one node for the Jepsen controller and clients, three for the Paxos servers. I wrote some Clojure that Jepsen executes to deploy my servers and run my concurrent clients.

Jepsen stores the history of each run and produces a timeline diagram, where each client process is a vertical column, representing one operation after another in sequence. Concurrent ops overlap on the horizontal.

Visualizing your test run is a good sanity check. For example, I briefly had a bug that caused all Paxos Phase 2a messages to be lost. That meant no values were accepted and all client operations failed, but linearizability wasn’t violated! As Lamport says, “Always be suspicious of success.” In other words, Jepsen checks safety, but you need other tests for liveness. At first, you can just see if the diagram looks reasonable.

Jepsen sees each test’s history as a graph of overlapping operations. It checks that there’s some way to transform it into a linear sequence, without violating real-world order, that makes the system behave like a “model” that you provide. (That’s linearizability.)

My main difficulty was comprehending what a model is and how to model an append-only list so Jepsen can check it. A model specifies how each operation should change a system’s state. This is so similar to a TLA+ “action” that I expected it to be easy; somehow I got stumped for hours and I’m still not confident. Perhaps it’s because the Jepsen tutorial and other examples showed me distinct write and read operations, whereas my system allows a single operation that both writes to the list and reads the list’s current value. Here’s my code, critique welcome:

; A Knossos model, validates that the Paxos system's state (which is an

; appendable vector of ints) behaves as it ought.

(defrecord AppendableList [state]

Model

(step [model op]

(assert (= (:f op) :append))

(if (nil? (:new-state (:value op)))

; op failed.

(do (info "failed" op) model)

; op succeeded. E.g., if state is [1 2] and we append 3, and the

; reply is [1 2 3 4] because another process appended 4, then op

; is {:value {:appended-value 3, :new-state [1 2 3 4]}}.

; Linearizability demands that [1 2] is a prefix of new-state and

; 3 is in the suffix.

(let [appended-value (:appended-value (:value op))

new-state (:new-state (:value op))

actual-prefix (vec-slice new-state 0 (count state))

actual-suffix (vec-slice

new-state (count state) (count new-state))]

(cond

(< (count new-state) (count state))

(knossos.model/inconsistent

(str "new state: " new-state " shorter than state: " state))

(not= state actual-prefix)

(knossos.model/inconsistent

(str "state: " state "not a prefix of new state: " new-state))

(not (some #(= appended-value %) actual-suffix))

(knossos.model/inconsistent

(str "appended value: " appended-value

" not in new values: " actual-suffix))

:else

(AppendableList. (conj state appended-value)))))))

To test Jepsen itself, I tried disabling an important rule in the Acceptor: it should accept a Phase 1a message only with a higher ballot number than any it’s seen, but I made it accept any Phase 1a message.

class Acceptor:

def _handle_prepare(self, prepare: Prepare) -> None:

# Handle Phase 1a mesage, see Fig. 3 in Chand et al.

# --------- COMMENTED-OUT TO PRODUCE AN INCONSISTENCY ------

# if prepare.ballot <= self._ballot:

# return

self._ballot = prepare.ballot

promise = Promise(self._ballot, self._voted)

self._send(prepare.from_uri, self._promise_url, promise)

Sure enough, Jepsen detected a linearizability violation, and logged a cute emoji:

Analysis invalid! (ノಥ益ಥ)ノ ┻━┻

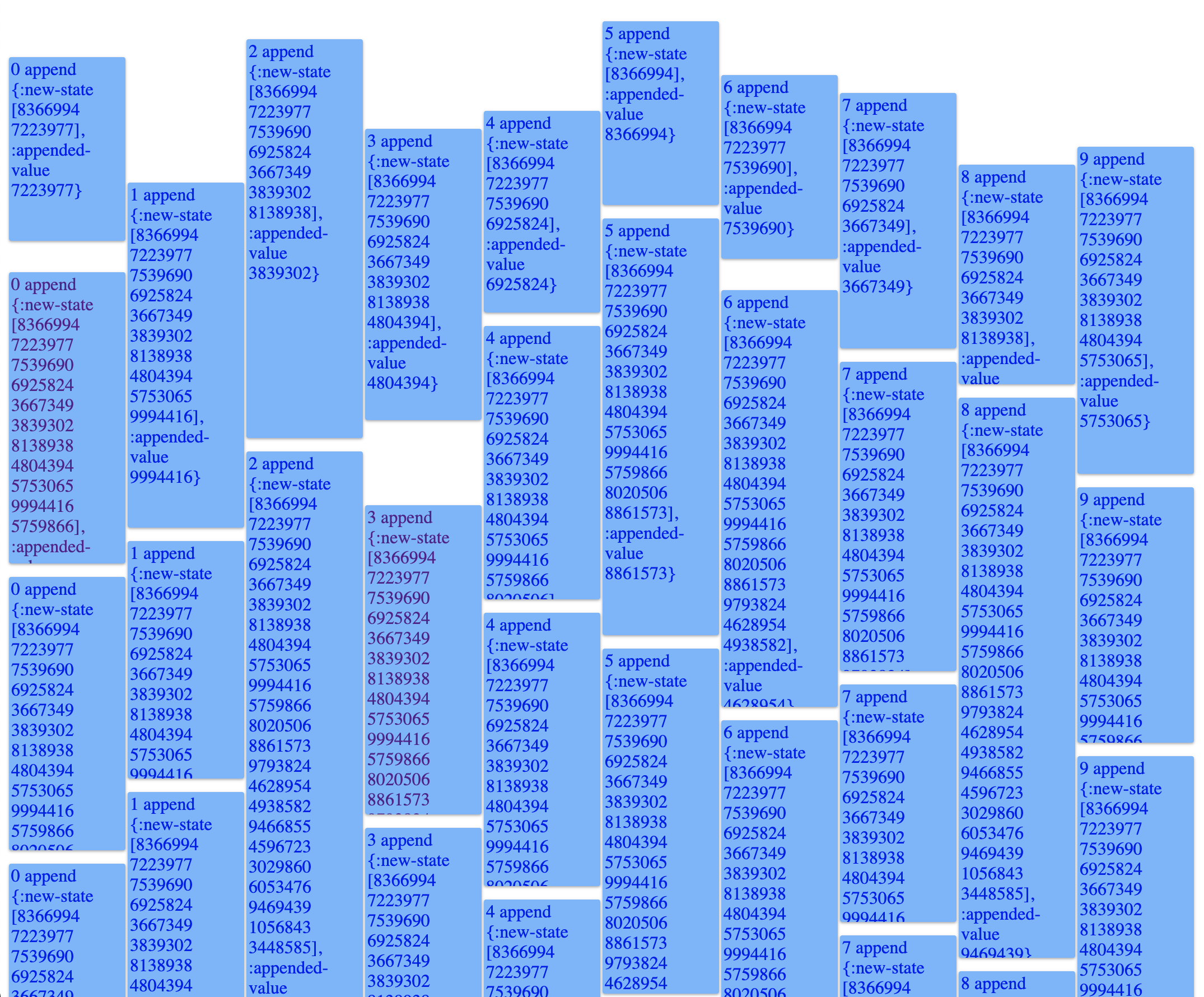

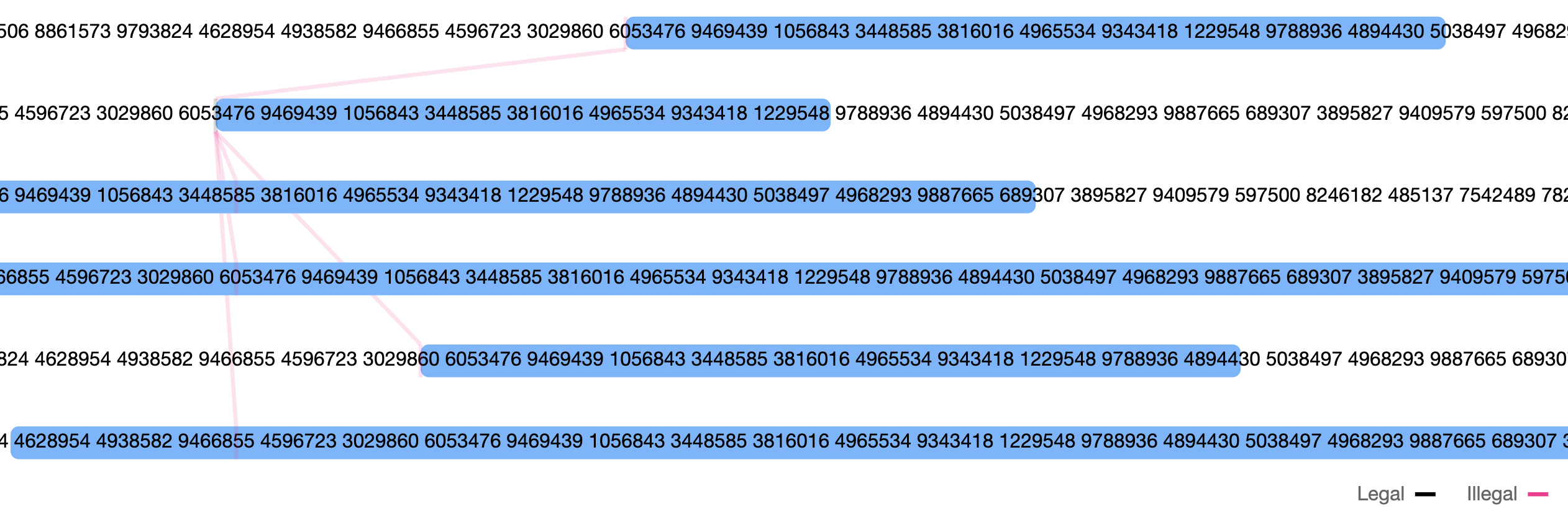

Jepsen draws a diagram which would be more legible if my system didn’t produce such large lists of numbers:

Despite the noise, you can see the basic problem: there’s a state (second from the top) with only red arrows leading from it, meaning any transition from that state would violate linearizability. By mousing over the boxes and reading the various log files, you could eventually diagnose the bug. At the end of each run, Jepsen saves its own log files in a timestamped directory, and thoughtfully copies each node’s logs into this directory too.

Conclusion #

Jepsen is a very powerful tool. Kingsbury’s making an admirable effort to build an on-ramp for ordinary programmers to test our systems with it. It’s not easy, but well worth the trouble. My direct interactions with Kingsbury were delightful. I opened two GitHub issues and he responded to both within hours. (One was my mistake, the other a lacuna in the tutorial.)

I still think it’s needlessly hard to understand Paxos, compared to Raft. You can read the Raft paper for one canonical description of a full-featured system, but I haven’t found an equally straightforward and full-featured description of Multi-Paxos. However, reading “Paxos Made Simple” and then trying to implement Paxos led me to a small eureka. I was thinking about Paxos as I rode the subway home late last weekend, and as I walked the final blocks in the cold from Union Square to my apartment, suddenly it all fit together. “Yes, Leslie,” I thought, “you’re right, it really is simple.”

Skunk by John James Audubon