Review: Exploiting a Natural Network Effect for Scalable, Finegrained Clock Synchronization

Christiaan Huygens by Caspar Netscher, 1671.

Christiaan Huygens by Caspar Netscher, 1671.

This is a review of Exploiting a Natural Network Effect for Scalable, Finegrained Clock Synchronization, from Stanford and Google researchers. It describes Huygens, a protocol for very accurate clock synchronization, plus (an undersold benefit) very accurate measurements of one-way network latency. I read it because the Huygens protocol is used by Nezha, which I reviewed last week. The Huygens and Nezha papers share two authors.

Motivation #

As Barbara Liskov wrote in 1991, there are practical uses of clocks in distributed systems, such as establishing an order of events on different servers without communication. In an especially insightful paragraph, the authors write:

In order to achieve external consistency, a write-transaction in Spanner has to wait out the clock uncertainty period, T, before releasing locks on the relevant records and committing. Spanner can afford this wait time because T is comparable to the delay of the two-phase-commit protocol across globally distributed data centers. However, for databases used by real-time, single data center applications, the millisecond-level clock uncertainty would fundamentally limit the database’s write latency, throughput and performance. Thus, if a low latency database, for example, RAMCloud, were to provide external consistency by relying on clock synchronization, it would be critical for T to be in the order of 10s of nanoseconds so as not degrade the performance.

NTP, the usual clock-sync protocol, is only accurate to a few milliseconds. More accurate protocols require specialized hardware. The Huygens protocol (“HOY-gons”, named for the inventor of the pendulum clock) gives nanosecond accuracy in ordinary data centers. The authors summarize it thus: “First, coded probes identify and reject impure probe data (data captured by probes which suffer queuing delays, random jitter, and NIC timestamp noise). Next, Huygens processes the purified data with Support Vector Machines, a widely-used and powerful classifier, to accurately estimate one-way propagation times and achieve clock synchronization to within 100 nanoseconds. Finally, Huygens exploits a natural network effect (the idea that a group of pair-wise synchronized clocks must be transitively synchronized) to detect and correct synchronization errors even further.”

The Buddy System #

Clock-sync protocols like NTP estimate network round-trip time (RTT) thus: server A sends a message called a “probe” to server B, which responds with an “ack”. Both messages are timestamped by the sending and receiving network interface cards (NICs). Server A averages the durations between probes and acks to estimate RTT. But some messages experience random queueing delays. Huygens wants to find probe-ack pairs that passed between the servers in minimum time without queueing delays; the authors call these “pure” probes. They use only pure probes for RTT and clock-skew estimation.

Huygens distinguishes pure and impure probes with a crafty little algorithm: Server A sends a probe, waits a small time s according to A’s clock, then sends a second probe. (For some reason these probe pairs are called “coded” probes.) If the time between the probes on the receiving server B is very close to s, Huygens calls both probes pure. (The duration s is small enough that the two servers’ differential clock drift is irrelevant.)

The Forbidden Zone #

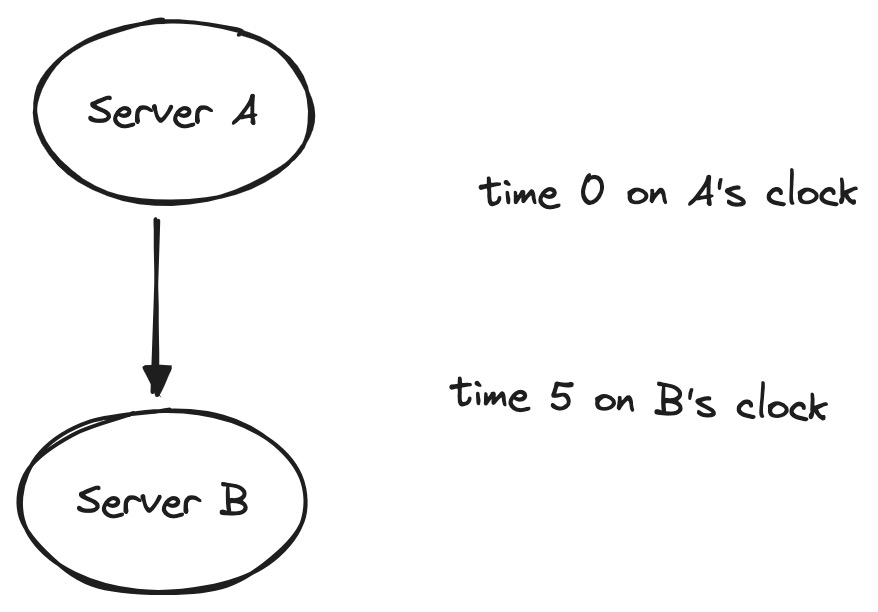

Huygens uses pure probes to calculate the largest and smallest possible clock discrepancies between servers. For example, if server A sends a probe at time 0 according to A’s clock, and B receives the probe at time 5 according to B’s clock, B’s clock can’t be more than 5 units ahead of A’s: otherwise the message would’ve arrived before it was sent, in absolute time. Thus a message from A to B reveals the upper bound of B’s clock skew relative to A’s.

A message going the opposite direction reveals the lower bound.

Any of these numbers could be negative: if the message leaves from A at time 0 and arrives at B at time -5, B’s clock can’t be more than -5 units ahead of A’s (i.e. it must be at least 5 units behind).

Even “pure” probes exhibit some random variation in latency. Quicker probes give tighter bounds: if the message leaves at time 0 and arrives at time 4, we’d know B’s clock can’t be more than 4 units ahead of A’s. But we don’t know how much of that difference is clock skew and how much is network latency—not yet.

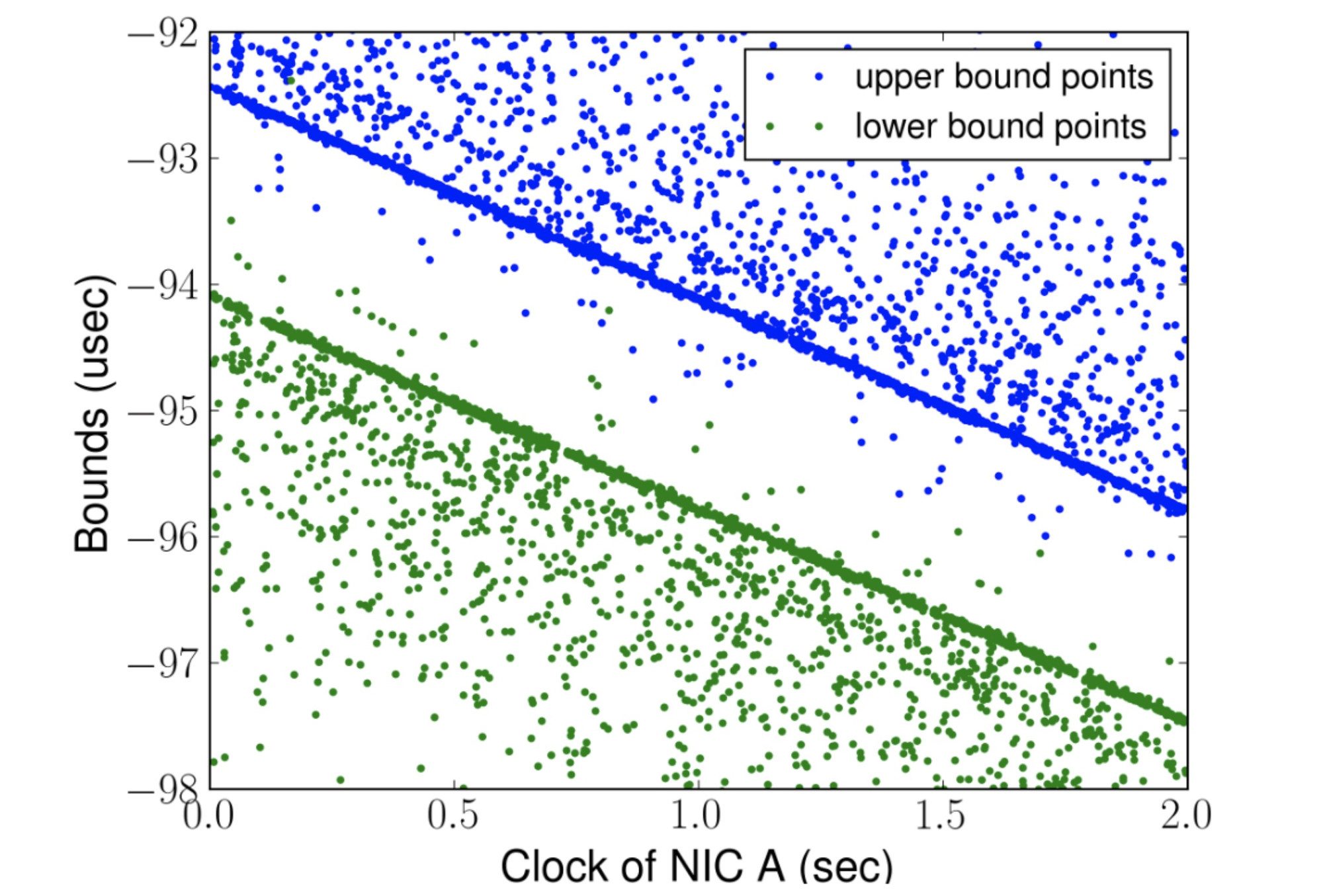

Over the course of seconds, as the servers’ clocks drift towards or away from each other, the bounds change, producing this difficult and delightful chart:

Figure 4 from the paper.

Figure 4 from the paper.

The quickest messages give the tightest bounds, visible as dense blue and green lines. Slowdowns seem to be randomly distributed, making sparse fields of blue dots above the least upper bound, and green dots below the greatest lower bound.

The handful of dots between the bounds are in the “forbidden zone”. They seem to be unusually quick messages that provide tighter bounds than the other dots, but it’s a lie. In fact, they’re an artifact of NIC timestamp noise: when a server sends a message, there’s an occasional delay of 10s or 100s of nanoseconds before it records the transmit timestamp, making the transmission time seem shorter than it is. This is small enough that these probes are considered “pure”, but large enough to hurt Huygens’s accuracy. Huygens uses a very well-known statistical method called a support vector machine to find the dense lines that border the forbidden zone and filter out the samples inside it.

Detecting Asymmetric Delays #

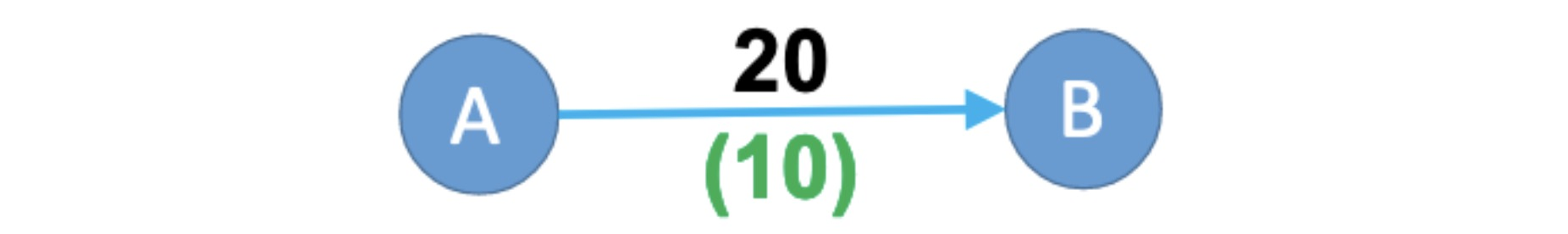

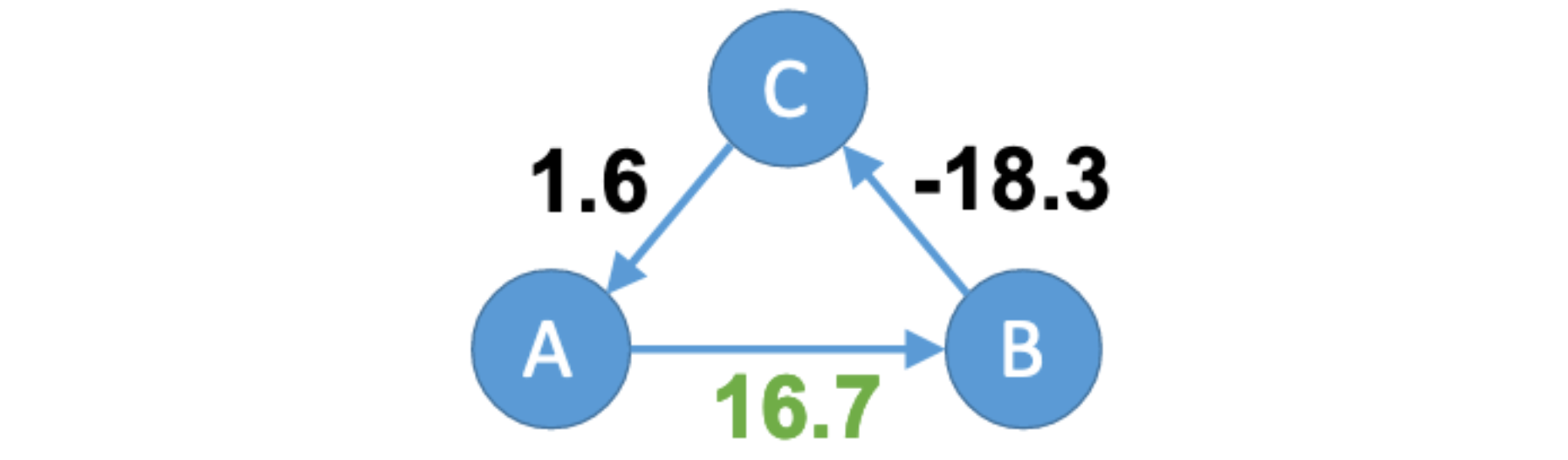

Other protocols like NTP assume symmetric network delays: they assume the one-way delay (OWD) from server A to server B is practically the same as vice versa. The Huygens authors find that this is mostly true in their data centers, but slight asymmetries violate this assumption enough to hurt clock synchronization. They exploit a natural network effect (hence the paper’s title): additional servers help detect asymmetries. For example (from the paper), say that servers A and B think that A’s clock is 20 units ahead of B’s, but due to asymmetry they’re wrong, A’s clock is only 10 units ahead of B’s:

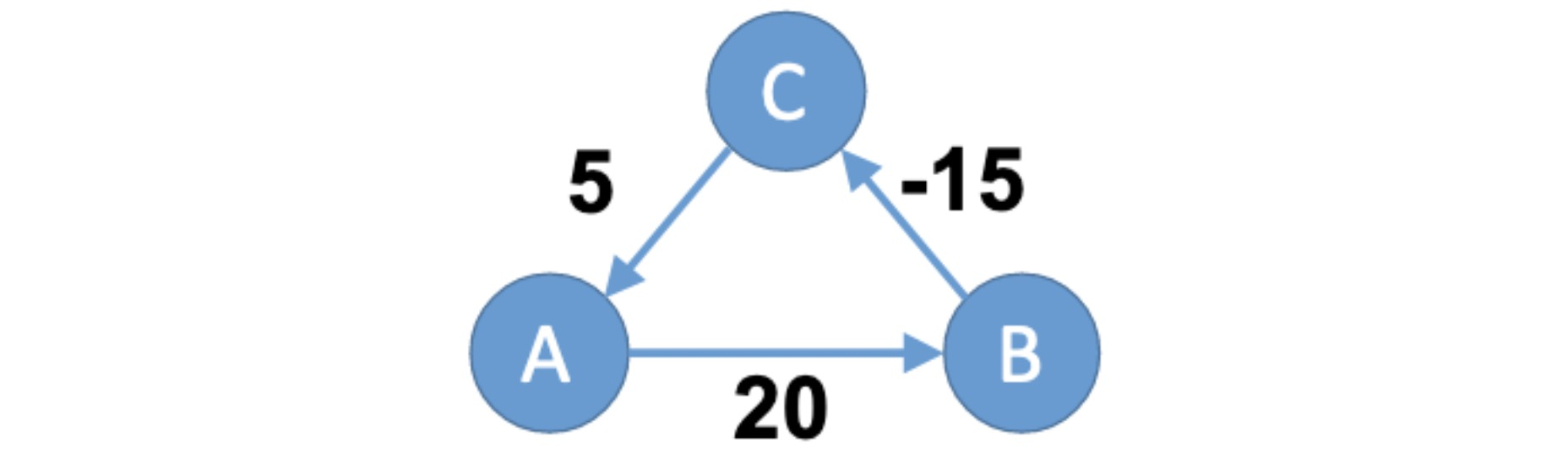

If these were the only servers, the error would be undetectable. But say there’s a server C that thinks it’s 15 units behind B and 5 units ahead of A:

This is impossible, because summing the offsets A→B→C→A we find a “loop offset surplus” of 10 units (20 + -15 + 5). Huygens evenly distributes the surplus among the pairwise offsets, improving accuracy. In this example, the offset from A to B is now estimated to be 16.7; not the accurate value of 10, but better than the wrong value of 20.

In a real data center, “each server probes 10-20 others, regardless of the total number of servers in the network”, and Huygens analyzes the entire graph of pairwise synchronized clocks.

Their Evaluation #

The authors built two testbeds, each with several racks and switches, and dozens of servers. One testbed represents, according to the authors, a “state-of-art data center”, and the other a “low-end commodity data center”. The two testbeds have different timestamping features in their NICs, and different network latencies.

I was wondering how they’d evaluate clock synchronization—after all, the problem they’re trying to solve is the lack of a perfect clock to compare to. They evaluate pairwise synchronization with a NetFPGA-CML board, which has four ethernet ports and one clock. They attach two separate VMs to two of the ports, and connect them to the rest of the servers in the low-end testbed. The two VMs are banned from talking directly to each other, they must sync their clocks via intermediate servers. Since the actual clock discrepancy between these VMs is zero, the authors can measure how closely Huygens has synchronized their clocks. They get a mean error of 13.4 ns and a 99th-percentile error of 30.2 ns; this is tiny, and the low variance is especially impressive.

There are additional evaluations that show that:

- If each server probes K other servers, clock error falls as K grows.

- Network load hurts synchronization, but not too much: a few probes can still get through without delay, and Huygens correctly identifies these as “pure” and uses them for clock sync.

- Huygens is orders of magnitude better than NTP.

My Evaluation #

The results in this paper seem exceptionally useful for distributed systems. Huygens appears to achieve incredibly tight clock synchronization, plus two features that the paper undersells: Huygens also measures the clock error bounds, and the one-way delay between servers. These three measurements could enable countless futuristic distributed protocols. Furthermore, the explanations in the paper are thorough and clear. The only part I found intimidating was their description of the loop-analysis algorithm, but I think that’s inherently complex.

Unfortunately, I can’t tell from the paper whether Huygens works in public clouds. Do customers like me have the required access to NIC timestamps? Do we need it? If Huygens works in public clouds, I wish this paper had evaluated it there. The Huygens code is closed-source, so third parties can’t test it themselves.

Several of the authors founded Clockwork, which “runs on all major clouds”, synchronizes clocks, and measures clock error bounds and one-way delays. Clockwork claims “sync accuracy as low as 5 – 10 ns with hardware timestamps, 100s of ns – a few μs with software timestamps.” It looks to me like they ported Huygens to public clouds using software timestamps, and its accuracy there is reduced but still great.

See Also #

- Quartz: Time-as-a-Service for Coordination in Geo-Distributed Systems, it’s open source.

- The Sundial paper and Murat’s summary. It focuses on a fault-tolerant, fast-recovering time sync service.

- This spectacular explanation of mechanical wristwatches is irrelevant, but read it; you’ll be forever changed.