Review: Leases: An Efficient Fault-Tolerant Mechanism for Distributed File Cache Consistency

Leases: An Efficient Fault-Tolerant Mechanism for Distributed File Cache Consistency, Cary G. Gray and David R. Cheriton, 1989. Old and good. I read this simple paper because it seems to be ground zero for timed leases in distributed systems, in which I’m now intensely interested.

The Protocol

The authors discuss a distributed file system, e.g. for a network of diskless workstations connected to a shared file server. (The file server itself is a single machine, not replicated. Yes, it’s a single point of failure. This is 1989.) The workstations can read or write files by exchanging messages with the server.

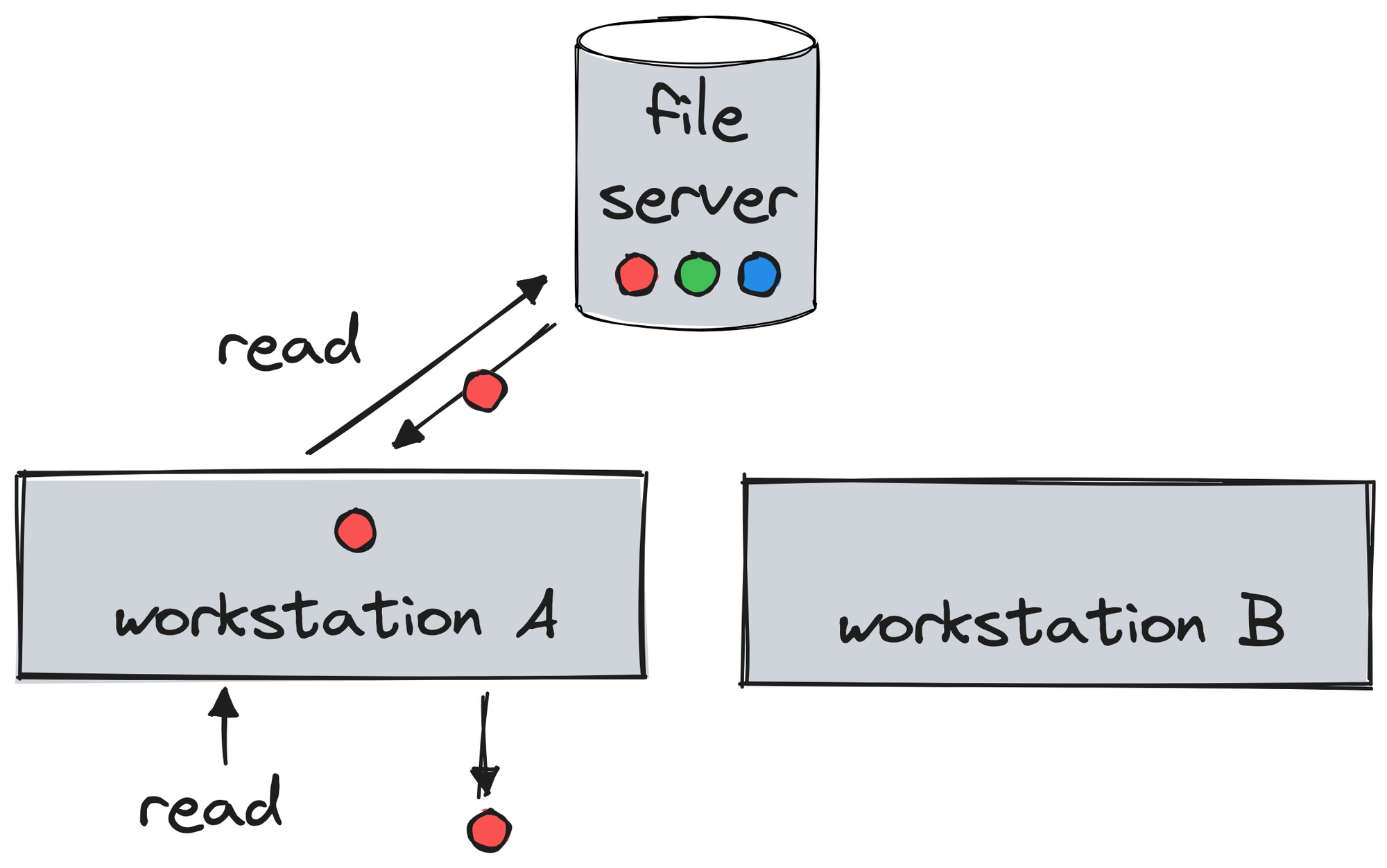

Each workstation is a write-through cache: when it reads a file, it caches it in its local RAM for future reads.

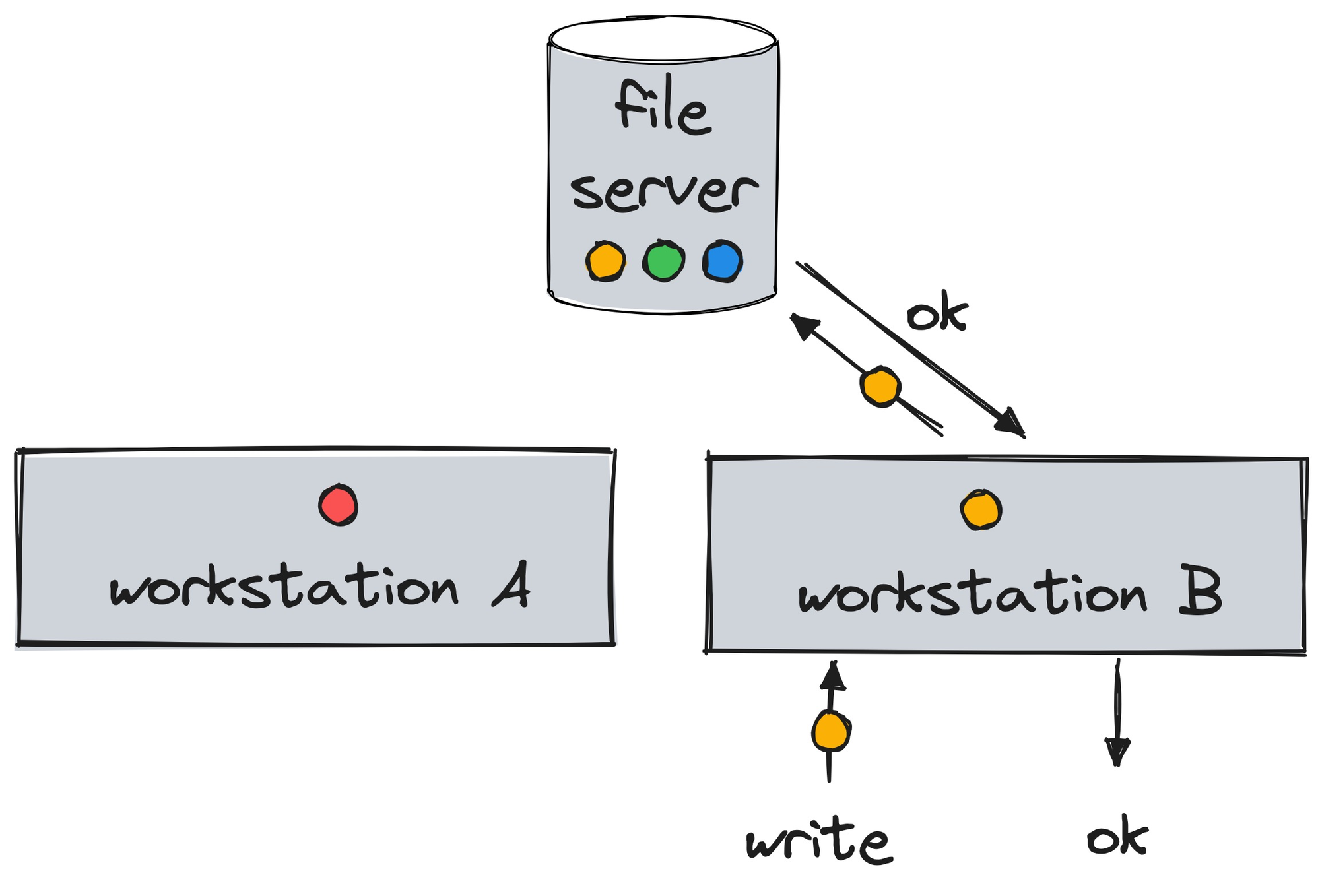

When a workstation updates files in its RAM, it synchronously updates the server’s copy.

Of course, all sorts of race conditions can cause inconsistency. Workstation A could read and cache a file, then workstation B updates it, then workstation A re-reads the file from its now-stale cache and sees outdated data.

The authors want to provide consistency: “By consistent, we mean that the behaviour is equivalent to there being only a single (uncached) copy of the data except for the performance benefit of the cache.” Their solution is a timed lease.

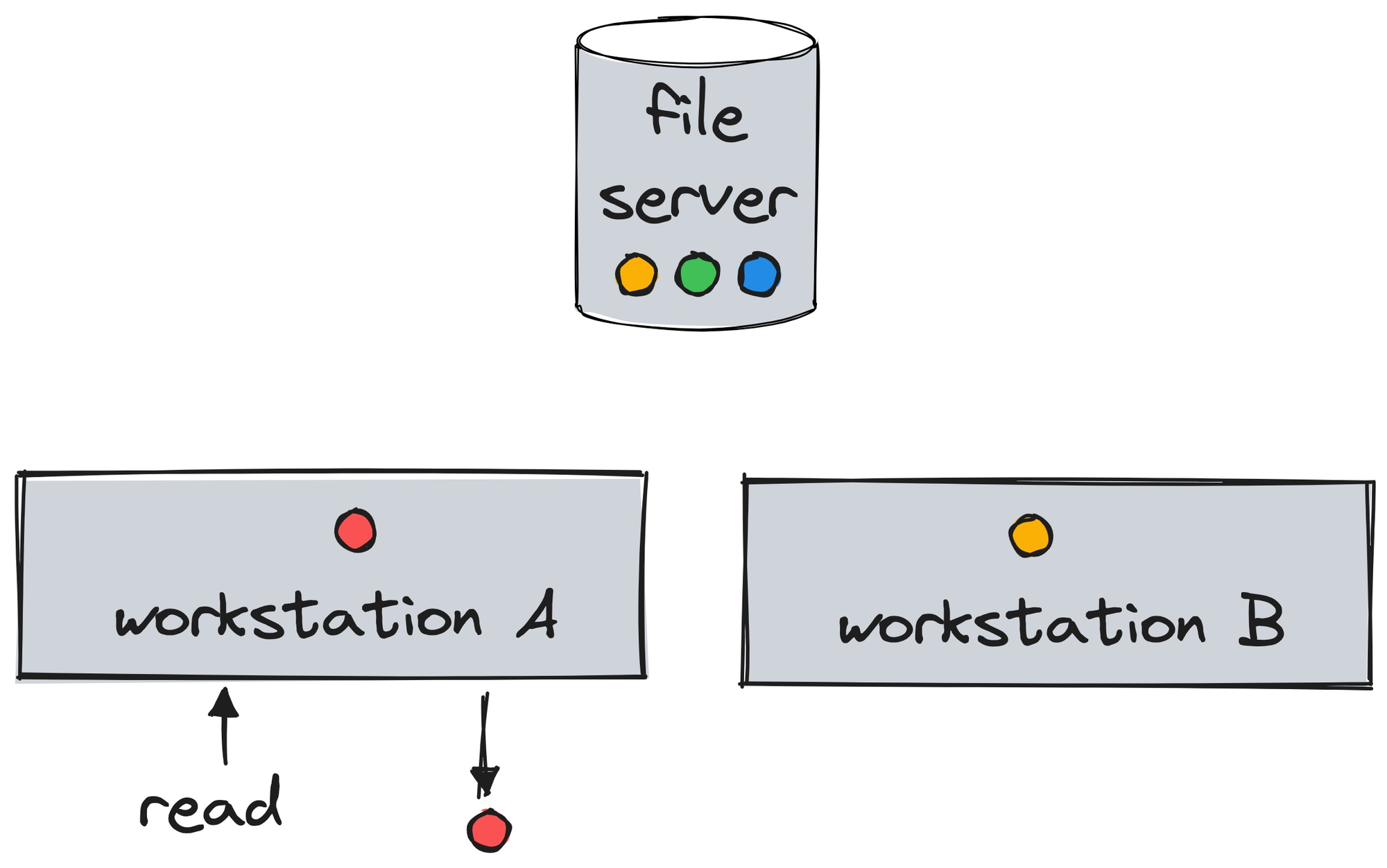

A cache using leases requires a valid lease on the datum (in addition to holding the datum) before it returns the datum in response to a read, or modifies the datum in response to a write. When a datum is fetched from the server (the primary storage site of the datum), the server also returns a lease guaranteeing that the data will not be written by any client during the lease term unless the server first obtains the approval of this leaseholder. If the datum is read again within the term of the lease (and the datum is still in the cache), the cache provides immediate access to the datum without communicating with the server. After the lease expires, a read of the datum requires that the cache first extend the lease on the datum, updating the cache if the datum has been modified since the lease expired. When a client writes a datum, the server must defer the request until each leaseholder has granted approval or the term of its lease has expired.

So before Workstation B can write to a file, it must acquire from the server a lease on that file, with a timeout that will expire some time in the future. Workstation B completes its writes while holding the lease, and either extends the lease or allows it to expire. When Workstation A then re-reads the file from its cache, it must get a new lease on it, thus discovering that the file has changed, and refresh its copy from the server. After this, Workstation A can keep reading the file until its lease expires. Meanwhile, no other workstation can modify it.

The server itself can read and write files, and it needs a lease to do so, the same as a workstation.

It seems that the system grants multiple shared leases for reading, or one exclusive lease for writing. The authors don’t say so, but they imply it. E.g., the passage above mentions “each leaseholder”, indicating there could be more than one per file. These days a paper like this would crush all ambiguity with pseudocode, a TLA+ specification, a formal proof, and a link to an open-source implementation on GitHub. I guess in 1989 you could mumble a few pages about leases and the ACM would publish it.

If a workstation or the server wants access to a file that’s already leased to another workstation, the lease-wanter can wait, or ask the leaseholder to relinquish the lease early. A leaseholder can proactively relinquish an unexpired lease that it doesn’t need anymore.

If many nodes want a lease on the same file, the server enqueues them. The paper doesn’t specify the scheduling policy, except to mention in a footnote that writers take priority.

Fault Tolerance

If a workstation gets disconnected from the other nodes, it might have crashed, or it might be partitioned and still reading from its cache any files for which it has valid leases. Thus to guarantee consistency, the server must wait for the disconnected workstation’s leases to expire before it can grant more on the same files. Since the workstation is practically stateless, crash recovery is trivial.

If the server crashes and restarts, it must remember all the leases it granted before. It could durably record each lease it grants, but that might make disk I/O a bottleneck. The authors propose that the server durably records only the maximum expiration time. When it restarts, it waits for that maximum expiration to pass before granting new leases.

The protocol is resilient to delayed or lost messages, but it does require all nodes' clocks to advance at the same speed, modulo a small, known epsilon.

Optimal Lease Terms

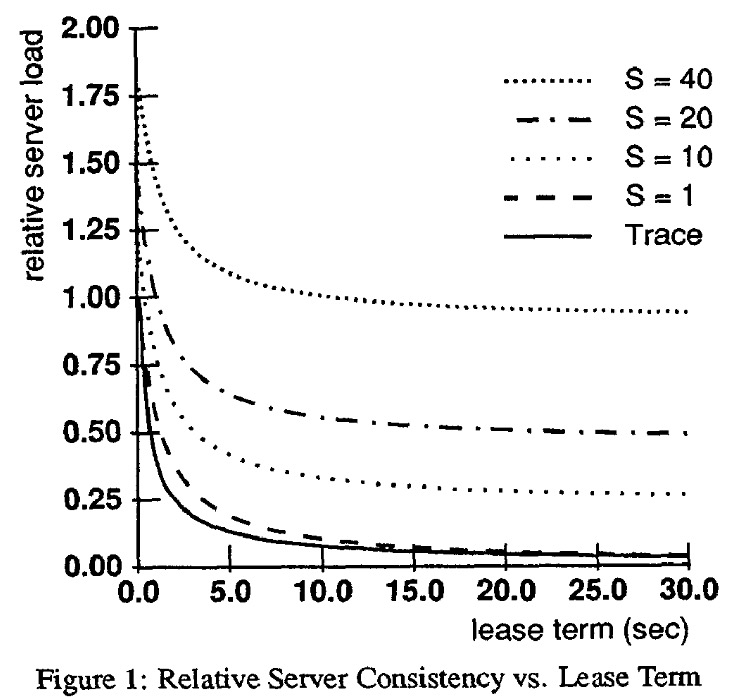

Short leases minimize recovery time after a workstation or server failure. They also minimize “false sharing”: when a node has to wait for a lease, although the leaseholder is no longer using it. Long leases reduce lease-requesting traffic and latency at the workstations.

The large portion of the paper constructs an analytical model of these tradeoffs. I’ll ignore this section since it’s fairly specific to the authors' system. Plus I’m generally skeptical of analytic performance modeling, compared to simulation.

There’s an interesting discussion, however, of the optimal lease terms for different sorts of files and workstations. The server should grant longer leases to more distant workstations to compensate for network latency. Operating system files are very frequently read and almost never written, so the server should grant very long read leases on them. In fact, it should just grant bulk read leases on whole directories of OS files, and proactively issue read lease extensions to all workstations so long as no write to the OS files is pending. On the other hand, the server should grant short leases on a frequently-written file. The authors say “a heavily write-shared file might be given a lease term of zero”, which I don’t understand—how can a workstation use a lease that’s already expired by the time the workstation knows it has acquired it? Anyway, the authors conclude, “a server can dynamically pick lease terms on a per file and per client cache basis using the analytic model, assuming the necessary performance parameters am monitored by the server.”

Their Evaluation

The authors evaluate performance not with a real-life test, but by applying their analytic model to some real-world data. They use a trace of file accesses from one workstation to one file server, while the workstation recompiled a program. There’s no contention in the trace (since there’s one workstation), so they simulate various levels of contention in their evaluation. Network latencies were measured in separate tests, then fed to the model. This is so many steps removed from reality, it wouldn’t fly in a modern research journal. However, I do appreciate this abstracted approach; it can be more revealing than testing a fully-implemented system with its adventitious complexity and noise.

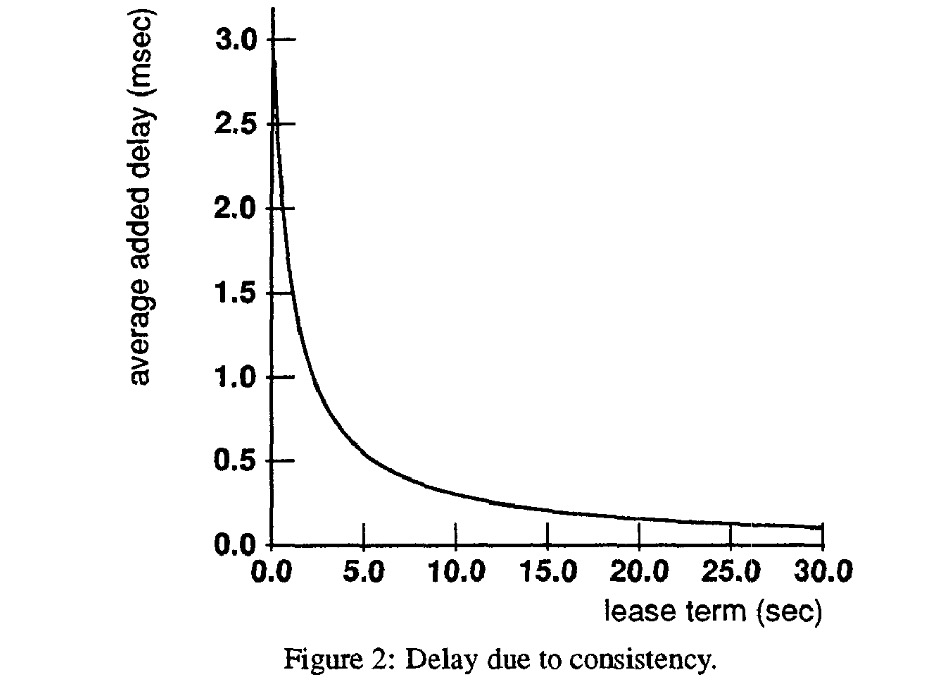

The authors measure server load (i.e., the number of messages it must process) for different numbers of workstations (the “sharing level”, S) and different lease terms. They set the server load to 1 with 1 workstation and zero-term leases, and measure other configurations relative to that one. The workload is 96% reads, so longer terms reduce server load because workstations can mostly read from cache. I’d be curious to see latency at the workstations, too. I’d expect longer terms to decrease latency in this read-heavy workload, and increase it in a write-heavy workload.

My Evaluation

A short and sweet paper, worth reading for historical interest. If I publish a paper about leases I’ll need to know what’s in this one so I can cite it. I wish they had described their protocol more precisely, perhaps in pseudocode, before they rushed to model it analytically and draw charts. But all is forgiven: this is the paper that coined the term “lease” and introduced the world to an elegant consistency technique.

See also:

- Review by the Morning Paper.

- Murat Demirbas, Do leases buy us anything?.

Image: Edwart Collier, 1662.