Review: Antipode: Enforcing Cross-Service Causal Consistency in Distributed Applications

In 2015 some Facebook researchers threw down a gauntlet, challenging anyone who dared to provide stronger consistency in big, heterogeneous systems. In 2023, some researchers (mostly Portuguese) responded with Antipode: Enforcing Cross-Service Causal Consistency in Distributed Applications. Antipode defines an interesting new consistency model, cross-service causal consistency, and an enforcement technique they claim is practical in such systems.

Motivating Example #

Here’s an example from the paper. A social network is composed of services:

My simplification of the paper’s Figure 2

This system has the following problematic workflow:

- Author uploads a post; it’s received by the Post-Upload service in Region A.

- Post-Upload sends the post to Post-Storage,

- … which saves the post to a local replica of its datastore.

- Post-Upload tells the post-id to Notifier,

- … which saves the post it a local replica of its (separate) datastore.

- Both datastores eventually replicate to Region B in arbitrary order.

- In Region B, as soon as Notifier replicates the notification,

- … it triggers Follower-Notify,

- … which retrieves the post from Post-Storage,

- … which retrieves it from its local replica of its datastore.

- Once Follower-Notify has the post, it relays it to Follower.

The problem, as astute readers can predict, is if Notifier’s datastore replicates sooner than Post-Storage’s. In that case, Follower-Notify will learn about the post too soon; it’ll try to retrieve it from Post-Storage but the post won’t be there yet.

This is a consistency violation of some sort—the paper will define it exactly, in a moment. We could prevent the anomaly by making all datastores replicate synchronously. In that case, once Post-Storage has acknowledged storing the post in Region A, it has also replicated it to Region B, so it’s certainly there by the time Follower-Notify tries to retrieve it. But this kills all parallelism. Maybe there’s a better way?

Causal Consistency Isn’t Enough #

What about Lamport-style causal consistency with logical clocks? This wouldn’t prevent the anomaly. The paper doesn’t explain in detail why, so I’ll try.

In Lamport’s algorithm, each process has a clock value (perhaps just an integer), which is incremented and propagated whenever processes exchange messages. Lamport clocks could prevent the anomaly if we had one replicated datastore:

- Post-Storage in Region A saves the post, gets a Lamport clock value of 42 from the datastore.

- Post-Storage in Region A directly notifies Post-Storage in Region B and tells it the clock value.

- Post-Storage in Region B reads from its replica of the datastore. It tells the datastore to wait until it’s replicated up to clock value 42 before executing the query:

Many datastores (including MongoDB) support causal consistency this way, and it would prevent the anomaly described above. This doesn’t work in the example from the paper’s Figure 2, however. The problem is, there are two datastores replicating concurrently in Figure 2. Causal consistency is a only a partial order, not total; it allows the Post-Storage’s or the Notifier’s datastore to replicate first. With multiple replicated datastores, the anomaly is allowed by causal consistency, so we have to define a stricter consistency level.

Cross-service Causal Consistency #

The Antipode authors define a new consistency level that prohibits the anomaly: “cross-service causal consistency”. They abbreviate it “XCY”, which perhaps makes sense in Portuguese. Cross-service causal consistency includes several ideas:

Lineage: A DAG of operations, partially ordered with Lamport’s “happens-before” relation. A lineage begins with some “start” operation, such as a client request or a cron job, and proceeds until each branch completes with a “stop” operation.

In Figure 2 there are two lineages: one is spawned when Author uploads a post. I’ll call this Lineage A. It has two branches (leading to Post-Storage and Notifier), and it includes concurrent replication of two datastores to Region B. The other lineage, which I’ll call Lineage B, is spawned when Follower-Notify in Region B receives the notification. Lineage B then reads from Post-Storage in Region B, and notifies Follower.

The authors use a data set from Alibaba, where lineages are hairy: “User requests typically form a tree, where more than 10% of stateless microservices fan out to at least five other services, and where the average call depth is greater than four. Additionally, this tree contains, on average, more than five stateful services,” i.e. services with datastores.

Reads-from-lineage: An operation b reads-from-lineage L if b reads a value written by an operation in L.

Cross-service causal order: This is denoted with the squiggly arrow ⤳. For two operations a and b, if a happens-before b or b reads-from-lineage L, where L includes a, then a ⤳ b. Cross-service causal order is a transitive partial order, like happens-before.

XCY: This is the paper’s new consistency level. An execution obeys XCY if you can find a serial order of operations obeying cross-service causal order.

XCY is the consistency level that Figure 2 violates! When Follower-Notify tries to read Author’s post in Region B, that should happen after all the events in Lineage A, including the replication of the post to Region B.

My Feelings About Lineages #

I feel uncomfortable, as if there’s a purer mathematical concept obscured by the specifics of microservice architectures. Why are the borders between Lineages A and B drawn where they are? Could we split these operations into more than two lineages, or combine them into one?

I think that a lineage is a general concept (“a DAG of operations”), but Antipode finds it convenient for microservice architectures to split lineages thus: Operations in a lineage are connected by happens-before. When a service reads a value from storage, this operation does not join the lineage that wrote the value. Instead, it’s connected by reads-from-lineage. The goal of “cross-service causal consistency” is to make a partial order of lineages, such that replicated data stores appear not-replicated. (I was confused about this until I read the paper’s appendix. You should read the appendix, too.)

I think there’s a more general idea of “recursive” or “nested” causal consistency trying to be born. This general idea would include lineages, defined however you want, and lineages could contain nested lineages. Cross-service causal consistency is a specialization of this general idea.

Tracking And Enforcing Cross-Service Causal Consistency #

This paper describes a system for enforcing XCY, called “Antipode”, which means “opposite side”; maybe this refers to end-to-end consistency guarantees across geographic regions. Or maybe it refers to mythical beings with reversed feet for some reason.

Anyway, whenever services exchange messages as part of the regular functioning of the application, Antipode piggybacks lineage information. Since microservice architectures already piggyback info for distributed tracing, Antipode doesn’t add much coding-time or runtime burden. Additionally, Antipode places shims in front of all datastores; the shims add lineage information to reads and writes. (Antipode borrows the technique from Bolt-on Causal Consistency.) Lineage info accumulates along causal branches within a lineage, and gets dropped whenever a branch ends.

Developers can customize lineage tracking; they can explicitly add or remove dependencies. If one lineage depends on another in a way that Antipode doesn’t detect, a developer can transfer lineage info between them.

(MongoDB drivers let you transfer causality info between sessions, too, although it’s basically undocumented; I explain it here.)

Antipode could enforce XCY automatically, on each read operation, but instead it provides an explicit barrier operation that developers must call to wait for dependencies to be satisfied. This seems error-prone, but it sometimes permits developers to reduce latency by carefully choosing where to place their barrier calls. The authors write,

One argument that can be made against barrier is that it is as explicit as today’s application-level solutions, since both of them require the developer to manually select its locations. What makes Antipode’s approach better suited is not only barrier, but its combination with the implicit/explicit dependency tracking, which keeps services loosely coupled and does not require end-to-end knowledge of what to enforce.

This bit about “loose coupling” is insightful: you can place your barrier call somewhere, and if you later add dependencies, barrier will enforce them without code changes. On the other hand, having one barrier call for all dependencies requires you to wait for all of them at once, including those you don’t need yet.

How does barrier know how long to wait?

Antipode’s

barrierAPI call enforces the visibility of a lineage. It takes a lineage as an argument and will block until all writes contained in the lineage are visible in the underlying datastores. Internally, abarrierwill inspect the write identifiers in the lineage and contact the corresponding datastores. For each datastore, barrier will call the datastore-specificwaitAPI, which will block until the write identifier is visible in that datastore. Note thatwaitis datastore-specific because visibility depends on the design choices and consistency model of the underlying datastore. Oncewaithas returned for all identifiers in the lineage,barrierwill return.

In our example, this means that before Follower-Notify retrieves Author’s post from Post-Storage, it calls barrier, which queries the Post-Storage datastore and waits until it’s sufficiently up-to-date.

This is an extra round trip (red arrow) even if the datastore is already up-to-date. I think this could be optimized away with something like MongoDB’s afterClusterTime, but Antipode’s API would have to change. Luckily, you can limit the consistency check to nearby replicas:

We implemented a practical optimization strategy specifically tailored for geo-replicated datastores. This involves implementing the wait procedure to enforce dependencies only from replicas that are co-located with its caller, thereby avoiding (whenever the underlying datastore allows it) global enforcement.

I don’t fully understand barrier from the paper’s description. If it’s waiting for all writes from Lineage A to be visible in Region B, how does it know about writes that Lineage A hasn’t even started yet? Must it wait for all branches of Lineage A to finish? If so, how? And what if an operation in Lineage A crashes or hangs?

Their Evaluation #

The authors evaluate Antipode with three benchmarks and a dozen brands of datastore, and ask 1) would there be XCY violations without Antipode, and 2) what is the cost of preventing them? The answer to question 1 is yes. For question 2:

- Lineage info adds 200 bytes to 14 kb per message in the authors’ benchmarks (developers might need to explicitly prune lineages in their own systems).

- Waiting for consistency increases latency, by definition.

- Enforcing XCY decreases throughput by 2-15%.

My Evaluation #

Cross-service causal consistency is a neat concept. The chief argument for it, buried in the middle of the paper, is decoupling: it permits microservices to read consistently from multiple replicated data stores, without knowing the details of the microservices that wrote to them. This limits the impact of changes to any part of your system. With Death Star architectures like Alibaba or AWS, decoupling is crucial.

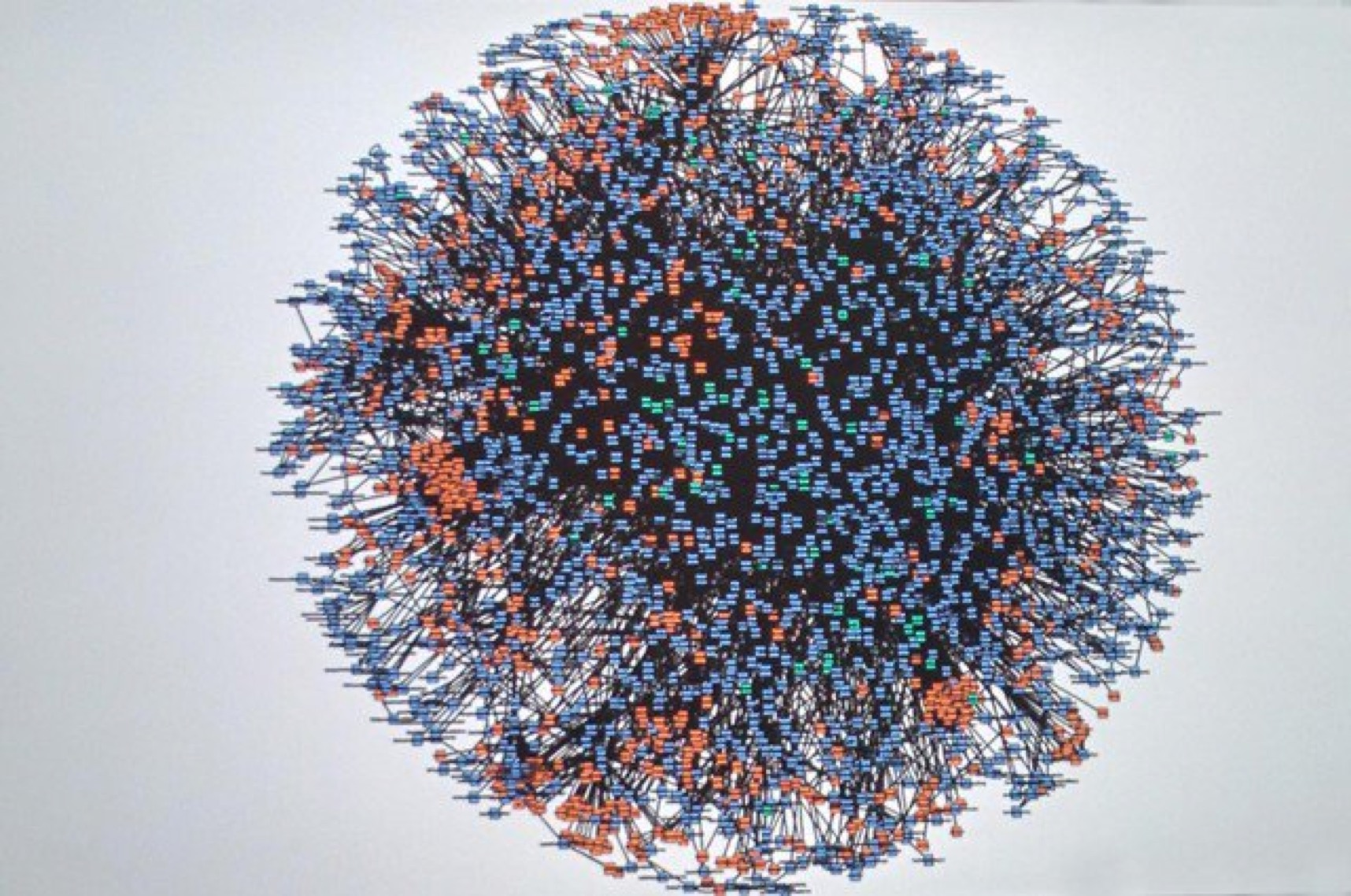

The AWS microservices “death star” in 2008

Antipode’s API is higher-level than manually enforcing cross-service dependencies. I think it could be useful as part of an even higher-level “cloud programming language” that automatically decomposes, distributes, and parallelizes high-level logic, while detecting consistency requirements and enforcing them. I’m aware of cloud programming language projects like Unison, Wing, Goblins, Hydro, Dedalus, Gallifrey, and so on. They’re at various stages of development and levels of abstraction. If this paper’s definition of lineage were generalized to encompass more kinds of causal relations among operations, it could express the constraints of a variety of constructs in high-level cloud programming languages, and something like Antipode could enforce them.

Further Reading #

Other systems that strengthen the consistency of existing systems: