Which Beings Are Sentient?

Which animals are sentient, and how can we liberate them from suffering? This is my January 23, 2025 dharma talk at the Village Zendo. I reviewed the philosopher Jonathan Birch’s book “The Edge of Sentience” and shared good news about humanity’s moral progress regarding animal welfare. Watch the video above, read the transcript below, or subscribe to my podcast.

TRANSCRIPT #

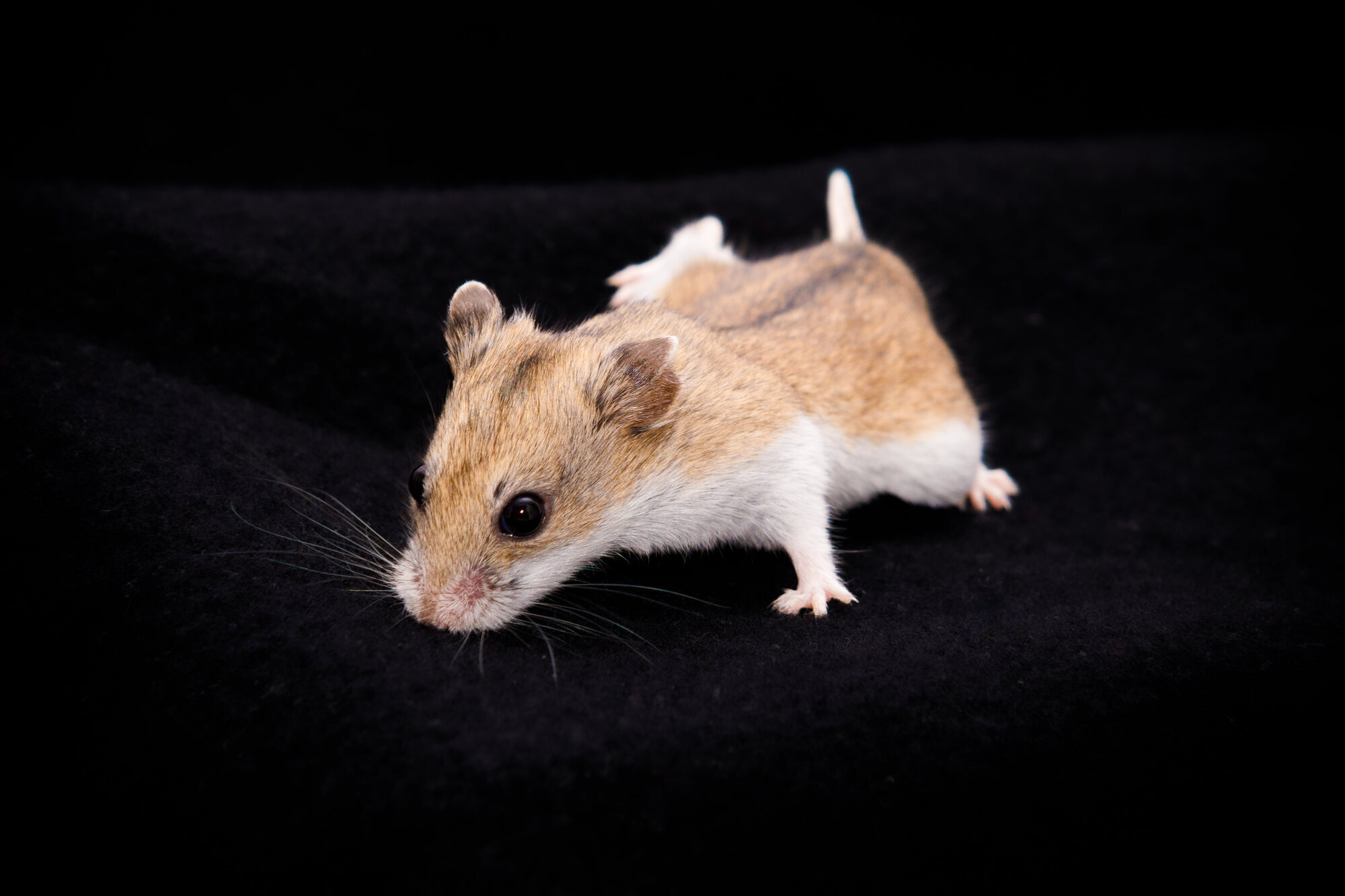

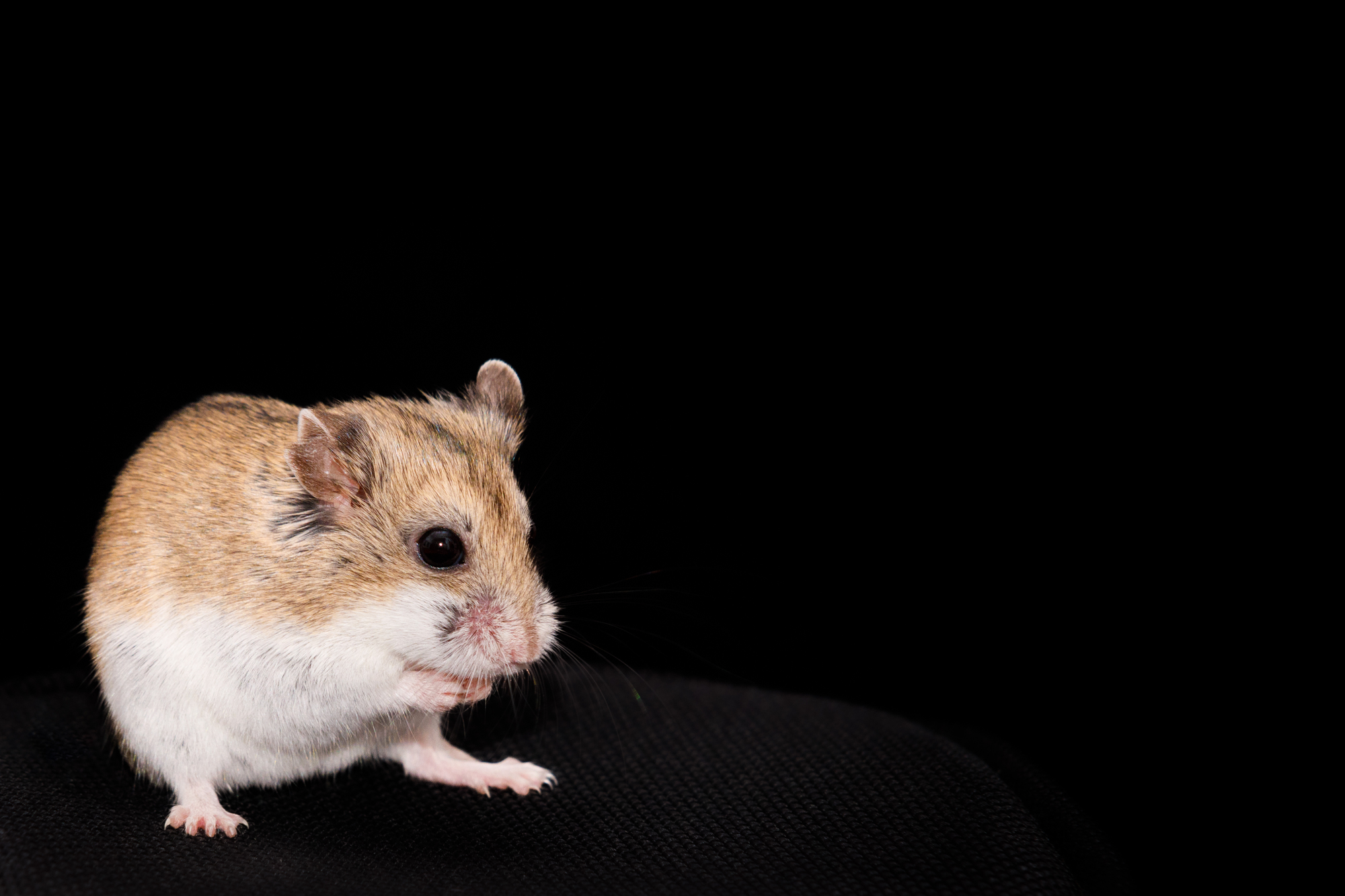

I would like to introduce you to somebody. This is Sojourner Truth Armstrong Davis, she is a Chinese dwarf hamster, and she is a little over a year old. We got her at a pet store across the river in Poughkeepsie, so her life is now more than half completed. She was in a cage with some sisters when we got her and we brought her home, and she’s been alone ever since. I mean, we’re her friends, but it’s unclear if she knows that we exist.

Actually, it’s unclear if she knows she exists.

This “problem of other minds” is a classic problem in Western philosophy. This question—what do we know about other beings’ internal experience, based on what we can observe about their behavior or their anatomy or by measuring their brains with EEGs or whatever? What do we know about other minds, and specifically, do we know whether they’re conscious or not? It seems obvious that I’m conscious—I know that I exist. I experience something, as Descartes said, “I think therefore I am.” Buddha said that this is kind of overstated, that based on our experiences, we tend to conclude that our consciousness is a lasting, separate thing that we need to protect and promote, whereas, in fact, my consciousness is more like a candle flame or a wave on an ocean or a bubble on a stream, as it says in the Diamond Sutra, I think. Temporary and not separate. But it doesn’t mean that I don’t exist! My consciousness is happening now, and other humans mostly behave like they’re conscious too. So it seems reasonable to guess that they are, but I can’t prove it. And with nonhuman animals, it’s much harder.

In what ways is Sojourner’s mind like or unlike mine? I’m pretty sure she has no language, although she makes a lot of noise. Does she think? She has some behaviors that sort of seem like planning. We feed her a variety of seeds and she doesn’t eat them all at once. She caches them around her cage. Well, if we give her fresh food, she eats right away. But if she gets food that seems like it’s going to last, she hides it. So this all seems pretty sophisticated. Mostly she saves her food in her little house, inside her cage, which is her nest, but then she also stores it in a few other places. Is she calculating that she wants backups, in case the main cache of food in her nest is lost somehow? I don’t know. She often shells a seed before she hides it. Is that to save space? I don’t know. When it’s cold in our house, she’ll stuff her little house with fluff for insulation. And one time, when we’d been gone for about a week and the house was quite cold, we set the thermostat down to 50 degrees, she had stuffed fluff around the outside of the house and piled it on top of her house to increase the insulation, which we hadn’t seen before.

Is that because she understands heat transfer and insulation in the way that a human does, or is it just an instinct? Her ancestors, who did that kind of thing at random, survived and passed on that instinct to her. I don’t know. Instinct seems more likely.

My own cognition isn’t as clear cut either! When it’s cold in the house, I get an extra blanket from the closet. Is that because I understand heat transfer and insulation, or is that an instinct? Or is that operant conditioning: I tried it in the past, and it felt warmer, so now I’ve trained myself to do that. Or is it imitation: I’m mimicking a behavior I saw my mother do when I was a child. As both Buddha and Freud have observed, we’re not very good at observing the operations of our own minds.

The world of her senses is very different from mine. Her hearing is about as sensitive as mine. Her ears are much cuter, but they’re not necessarily better. I can hear low tones better than she can, whereas she can hear much, much higher tones. So the world would sound different to her than to me. I couldn’t find any studies on dwarf hamster olfaction, but if she’s anything like a mouse, then she has three or four times as many olfactory genes as I do. So she can smell a much wider variety of scents, and she’s much more sensitive to subtle smells than I am.

Her vision is not very good. It’s blurry. She can’t focus on things unless they’re right in front of her, in the middle of her vision. She can barely see green and blue. She can’t see red at all. But her night vision is fairly good, and she has a very wide peripheral angle. So she seems to be optimized for detecting an owl swooping down on her in the dark, and for detecting a dark corner that she can run to to escape it. She also has very long whiskers. They’re half the length of her body, and she uses her whiskers and her smell to navigate. I think that the sensations of her whiskers must be very vivid to her.

I have no idea what any of this is like. What is it like to have her mind and body? The philosopher Thomas Nagel, in 1974 wrote an essay, “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?”, where he talked about a bat’s echolocation. He argued that with the bat’s echolocation, even if you understood everything about the physics of its ear and its neurons and its nerves, even if you could model this all with equations, you still wouldn’t understand what it’s like to be a bat. And with Soji as well, her sensorium and her consciousness are just irreducibly different from ours.

Is Soji sentient? She seems quite emotional. When I pick her up, she usually clicks her teeth together. This is called bruxing, and people agree that rodents make this sound when they’re happy. And normally, when I pick her up, she might also chatter, and I have no idea what that means. That might be happy too, because she makes this noise when I put her in her plastic ball, and she seems to enjoy running around the house, banging her plastic ball into things, so maybe that means she’s happy. But then she also makes that chattering sound when I put her back in her house. And she also tends to make it just when she’s sitting and there’s absolutely nothing going on, that’s actually when she’s the loudest. So maybe she’s announcing that this is her territory, wherever she happens to be. Maybe she’s horny. Maybe she’s expressing something that’s beyond human comprehension. I don’t know.

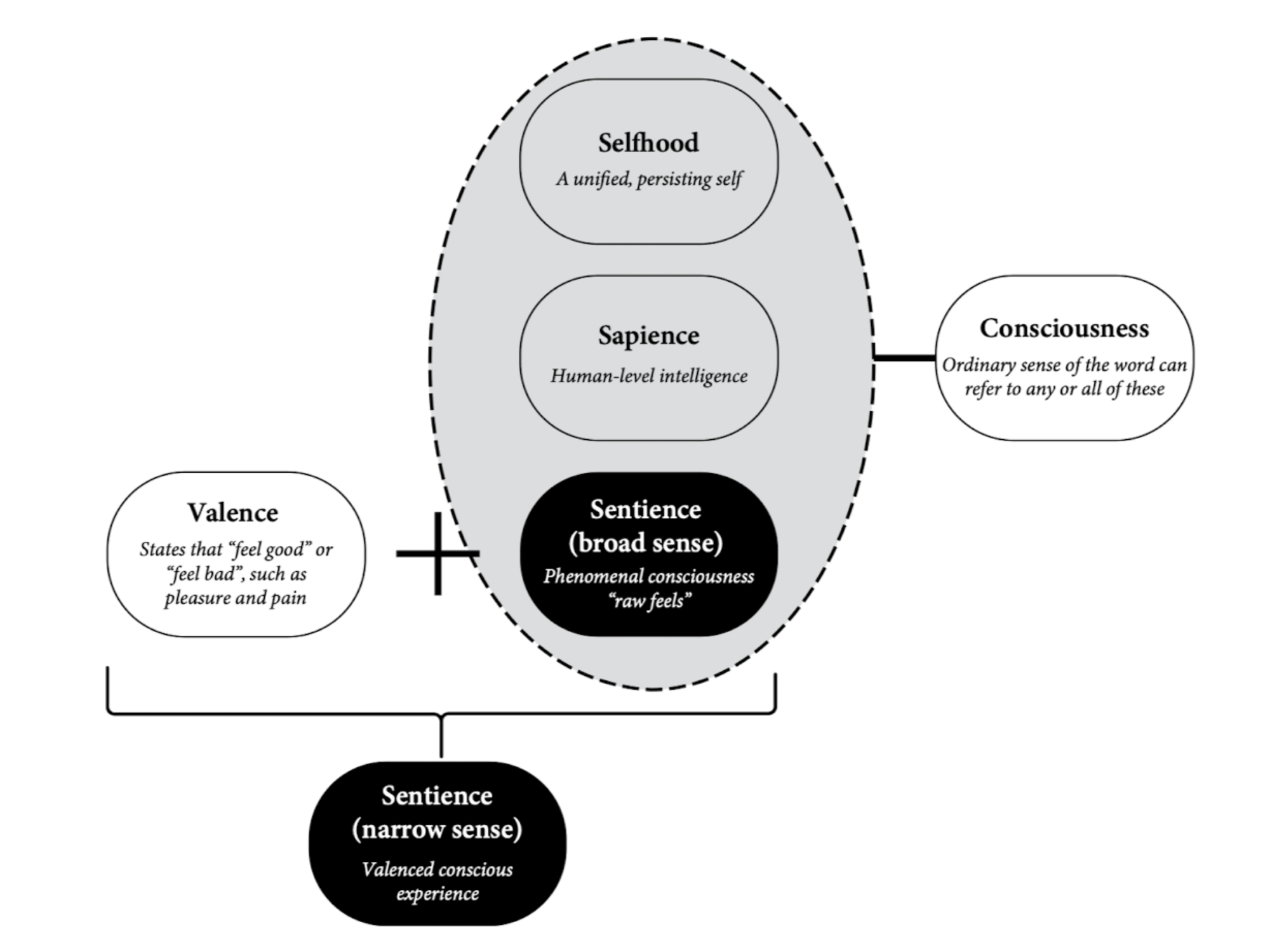

I’m in the middle of this fascinating book called The Edge of Sentience, which was published last year. It’s by the philosopher Jonathan Birch (who has nothing to do with the John Birch Society). It was published last year. It’s a free download from edgeofsentience.com or you can buy it. Birch is proposing an ethical framework for deciding which beings might be sentient or not, because if they are sentient, then we have an ethical duty not to cause them undue suffering. Birch starts out by talking about consciousness. He distinguishes some aspects of the mind that we might call consciousness. And he breaks it down into three meanings.

The first is selfhood, what we were talking about, this experience of being some sort of lasting single thing. And then there’s also sapience, which is intelligence: learning, problem solving, analyzing. And then finally, there is what he calls the “broad” sense of sentience, which is phenomenal consciousness, or “raw feels”, just bits of experience in time. And he says that if you combine this with valence, which is having experiences that feel good or feel bad, then these two things together, having consciousness and feeling good or feeling bad, this is the “narrow” sense of sentience, which is having valenced conscious experience. Any being, any system of neurons or software or whatever, that can have valenced conscious experiences, this is a sentient being, and we have a duty not to make it suffer.

So he’s trying to build this ethical framework for dealing with creatures where we’re not sure if they’re sentient or not. So he says,

A sentient being (in the sense relevant to the present framework) is a system with the capacity to have valenced experiences, such as experiences of pain and pleasure.

And if a being might be sentient, then he says, we have a duty to avoid causing gratuitous suffering to this being:

Framework Principle 1. A duty to avoid causing gratuitous suffering. We ought, at minimum, to avoid causing gratuitous suffering to sentient beings either intentionally or through recklessness/negligence. Suffering is not gratuitous if it occurs in the course of a defensible activity despite proportionate attempts to prevent it. Suffering is gratuitous if the activity is indefensible or the precautions taken fall short of what is proportionate.

So he’s not proposing to outlaw all meat or all animal research, just causing gratuitous suffering. This seems reasonable to me, and what I think is really interesting about Birch’s book, and what has been the most newsworthy aspect of it, is that he is trying to minimize ethical risk, moral risk, and this is the risk that we could be causing suffering to a sentient being without knowing it.

In a way we’re already familiar with moral risk. If I drop a thumbtack on the ground in a public place where people might walk barefoot, I clearly have a moral duty to pick it up, even though I might never know that somebody steps on it after I leave. They might not be permanently damaged, but it would be painful, and I have a duty to avoid the risk of causing suffering to that sentient being in the future.

Birch is talking about a different sort of moral risk. Think about dropping a live lobster into boiling water. There’s no question about what’s going to happen to the lobster, but there is a question about whether it’s a sentient being who feels pain, experiences it, in some way that we are morally obliged not to cause. If so, boiling it alive is immoral. So there’s some doubt whether it’s a moral or not, and it hinges on the lobster’s sentience. We may never know for sure, but it’s easy enough to avoid boiling lobsters alive. So in Birch’s opinion, we should do that to avoid the risk of causing suffering without knowing. Birch cause calls this the “precautionary principle”, and I think it’s a really interesting way to think about ethics.

So Birch divides all systems into three categories, and system is a deliberately vague and maybe strange word for a being, but it encompasses animals, plants, maybe it encompasses ant colonies as a whole, and it encompasses artificial intelligence, if such a thing already exists. So bring in large language models like GPT, just because it’s such a weird outlier, so that it helps us think about the whole range of possibilities. Here are Birch’s categories:

Number one, sentience candidate. This is the highest level. We’re not sure it’s sentient, but we’re pretty sure, and sentience candidates are anything where there’s evidence that these beings could experience pain and pleasure. We have some idea of what might cause pain and pleasure to them. So obviously, we can guess that all mammals feel pain, they react the same way to the same painful stimuli, and they have the same brain structures for experiencing the pain as we do, so mammals almost certainly sentient. Birch thinks that all adult vertebrates—mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians—are also sentience candidates, but not necessarily vertebrate embryos. So, fish eggs probably are not sentient. Probably don’t have to worry about causing suffering to them.

When it comes to invertebrates like insects, insects don’t seem to feel pain if their exoskeleton is damaged, interestingly, maybe because there’s no point evolving that, since their exoskeletons can’t heal. But it’s possible that they do feel pain if they’re poisoned or heated. Birch analyzes their brain structures and behavior and says that insects are sentience candidates too, and he says that we should take proportionate steps to avoid gratuitous suffering to them. We don’t need to be as careful about causing pain to bugs as to hamsters, but we should take proportionate steps.

The second category for Birch is an investigation priority, and Birch puts some snails and worms here. Interestingly, he thinks spiders are less likely to be sentient than bugs, and there’s a whole chapter of brain structure analysis to explain why. Since the risk that these are sentient beings is lower, we don’t have to be as cautious about causing them suffering, but we should hurry to figure out whether they should be upgraded or not. So these are priorities for us to investigate further.

Finally, the third category is not sentient. Birch doesn’t think that plants, single celled organisms like bacteria, rocks, oceans, the earth, are sentient. These beings or things, can have very complex behaviors, but they don’t have neurons or anything like them, and so Birch doesn’t think that they experience anything.

What about a large language model like GPT? We don’t know what it might find pleasurable or painful. It’s possible that asking it for a recipe is the equivalent of giving it an orgasm, and that asking it to write a poem is the equivalent of boiling it alive. But there doesn’t seem to be any way to know. There’s no behavior it evinces that resembles pleasure or pain, and it doesn’t have any structures that are anything like those with which animals experience pleasure and pain. So GPT is, for the moment, considered not sentient. My personal opinion here is that large language models are going to top out at high intelligence, but not sentience. They can think, but they can’t feel. Artificial intelligence will eventually be sentient, but it will be some other architecture, some other method of simulating intelligence, that will also feel. Birch thinks that we need to be very careful not to accidentally create a sentient artificial intelligence that suffers without our knowing it, because that would be a moral risk.

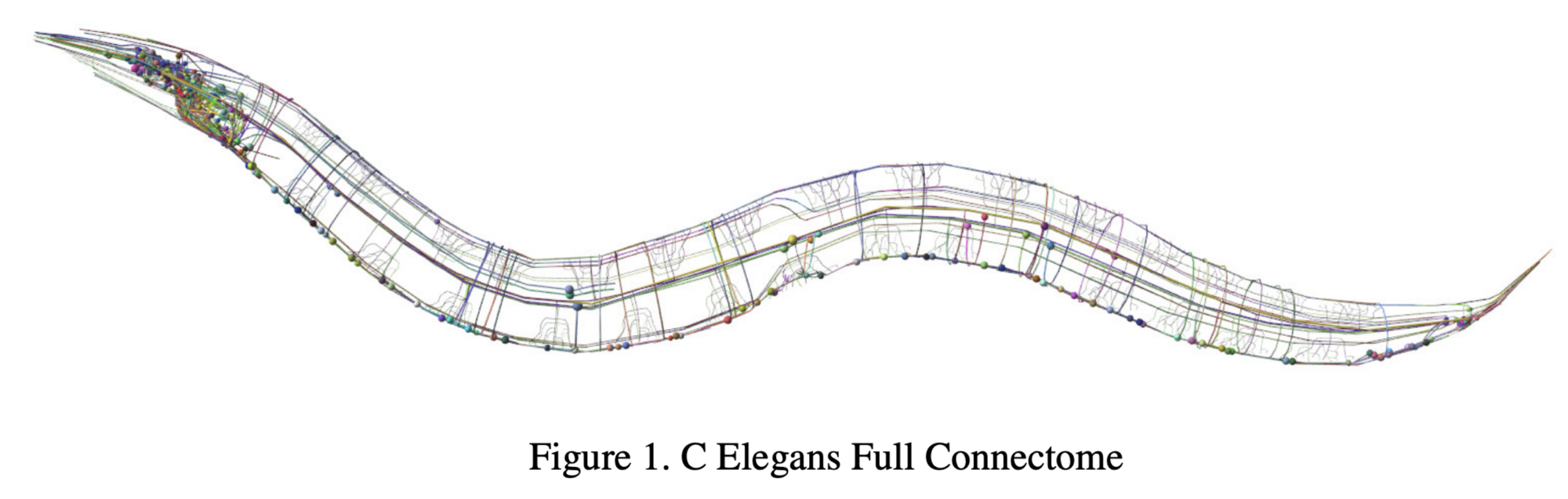

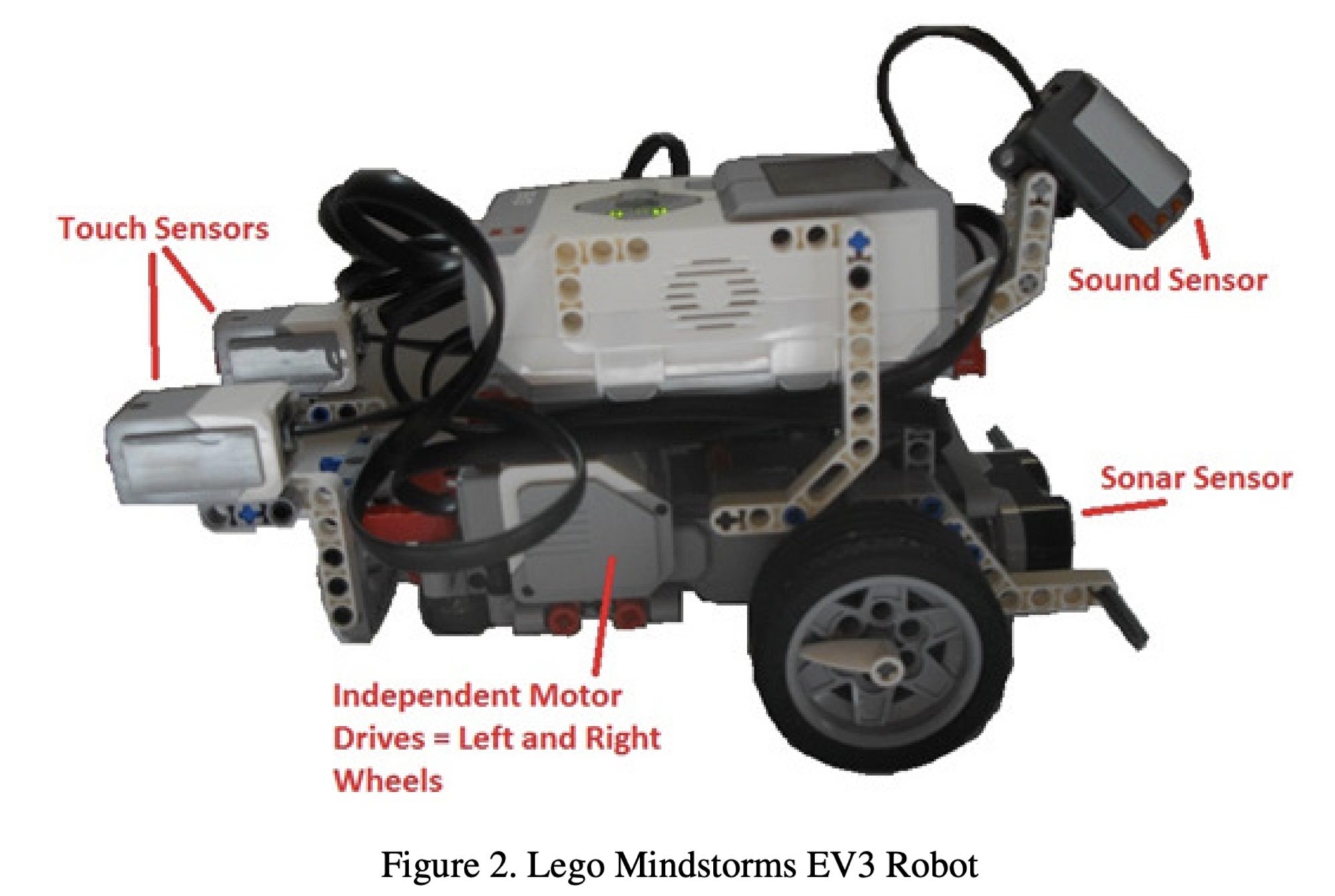

There’s this very interesting example called OpenWorm. It’s a research project to simulate in software every neuron of the tiny worm called C. elegans. So C. elegans, the real worm, has exactly 302 neurons. Every adult C. elegans has the same neurons, connected in the same way. Researchers have just mapped them out and simulated them in software. And this project is called OpenWorm, and it has many contributors.

Recently, a researcher connected up the worm neuron simulator to a physical robot made out of Legos, and it sort of maybe a little bit behaves like a worm; it navigates the space using some of the same methods that a worm would use.

So this is an interesting example, because Birch thinks that a C. elegans, a real one, is an investigation priority. What about a simulation of a C. elegans worm? I think that’s an investigation priority too. And if the worm were upgraded to a sentience candidate, something that we really have to avoid causing suffering to, what about the simulation of it? I see no difference. I don’t think that the hardware matters at all. I think it’s just software. I think that a simulation of a sentience being is sentient, and we must avoid making such a thing suffer.

Okay, so this is a dharma talk. What are Buddhists supposed to think about all of this? I’m reading this excellent book, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics by Peter Harvey, published in 2000. It’s got a lot of early Buddhist teachings, from the Pali canon, which I didn’t know until I read it, because I’ve only practiced Zen. In Zen, when someone asks a question, the teacher answers with riddles and quotes ancient Chinese poetry and says, you know, “The butterfly carries the precious jewel over the mountain.” So whenever I encounter early Buddhism and Shakyamuni Buddha, I really enjoy them. The old man was an intellectual. He thought everything through, and when somebody asked him a question, he would typically answer it in detail and tell you what he thought. And it’s clear that Buddha was very concerned about nonhuman animals. Indian religions in general are very concerned with animal welfare, in a way that might be unique among world religion families. Maybe because they say that humans are reincarnated as animals and vice versa. Or maybe the causation goes the other way: maybe they respect animals so much that they see no reason why humans couldn’t be reincarnated as animals.

Both Hinduism and Buddhism teach that each of us has been, in some past life, a worm, a ghost, a God, a hamster, and will be again. Any being we ever meet at any time has at some point been our parent or our child in some past life that we both had, and we will have this relationship again in the future. According to the Pali canon, Buddha said,

This samsara is without discoverable beginning. A first point is not discerned of beings roaming and wandering on, hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving.

Whenever you see anyone in misfortune, in misery, you can conclude: “We too have experienced the same thing in this long course.”

I love Buddha’s sort of scientific worldview—he doesn’t know. He says samsara’s without discoverable beginning.

Or more concisely, in another sutra he says,

The bones you’ve left behind in transmigration are greater than a mountain.

All these bodies you’ve died as, are greater than a mountain. But you don’t have to believe in reincarnation in this way, to see that we all experience misery. We all yearn to be liberated from suffering, and so it’s natural to feel sympathy for anybody who’s suffering.

Early Buddhist ethics teaches that harming a big, complex animal is worse than harming a small or simple one, and this is similar to Jonathan Birch’s framework. But on the other hand, Buddha didn’t seem to spend actually all that much time distinguishing between sentient and non sentient beings, like asking, is this or is this not? In Pali, he just talked about sattas, which is equivalent to the Sanskrit sattvas. In general, when we vow, as part of the Four Bodhisattva Vows, “to save all sentient beings”, in English, this, I think, comes from the Avatamsaka Sutra, the Bodhisattva vows of Samantabadhra. Or at least that was maybe an influence on it, via Chinese and so on. And Samantabadhra just says “saving sattvas” in Sanskrit, “saving beings”, maybe with the implication that sattvas are sentient. Certainly, if they’re worth saving, they must be. But it’s not a division between sentient and insentient that Buddhism really emphasizes.

Buddha, his goal was to free beings from suffering, by teaching them about the causes of suffering and the methods of being liberated from suffering. As we learn about suffering and we see that we’re trapped in it, and so is everybody else, it’s natural for us to be sympathetic for each other’s misery. Everybody similarly hates pain, yearns for peace.

Buddha taught that we shouldn’t cause suffering for any sentient beings, nor kill them. In the Dhammapada, which is the oldest Buddhist scripture, and maybe the most plausibly related to what the old guy actually said, he’s quoted as saying,

All tremble at punishment,

Life is dear to all.

Comparing others with oneself,

One should neither kill nor cause others to kill.

The early sutras say that we should help other beings and not cause them suffering, because that’s essentially good, but also acting this way is good for me. It accumulates good karma for me, and that good karma kind of pushes me along, gives me momentum to achieve escape velocity from suffering and achieve nirvana. But doing good because it’s going to be good for me, is only sort of good. Doing good for goodness’ sake is best, and your intention when you act is really key. Buddha said that if you harm unintentionally, it won’t cause you to suffer in the future. And if you cause good by accident, it won’t help you in the future either. This is in contrast to Jainism, another Indian religion that was arising around the same time in India. In Jainism, unintentionally harming a bug is quite bad, not as bad as intentionally, but still something that you work very hard to avoid. Even today, you’ll see Jain monks often wearing a mask to avoid accidentally inhaling a bug, sweeping the ground to avoid accidentally stepping on one. They even are so concerned about killing plants that they won’t eat root vegetables, like digging up a carrot kills the carrot, whereas plucking a fruit leaves the tree intact, and so they don’t eat root vegetables. Buddhists are a lot more relaxed about this stuff. In Theravada, they’re vegetarian, and they certainly try to avoid killing bugs, but they don’t go quite so far, because as long as your intentions are good, that’s probably good enough.

But Buddha said to think carefully about the consequences of your actions. So if you’re just like a well meaning idiot, obliviously causing carnage everywhere, that’s not the path to nirvana either. So I think Jonathan Birch’s framework is largely generally compatible with Buddha’s teaching here too. If we suspect that insects experience pain, for example, we shouldn’t ignore the possibility of that inconvenient truth because it would, it would be inconvenient for us. We should be curious. We should investigate whether they’re sentient. We should be willing to change our behavior if it turns out that they might be.

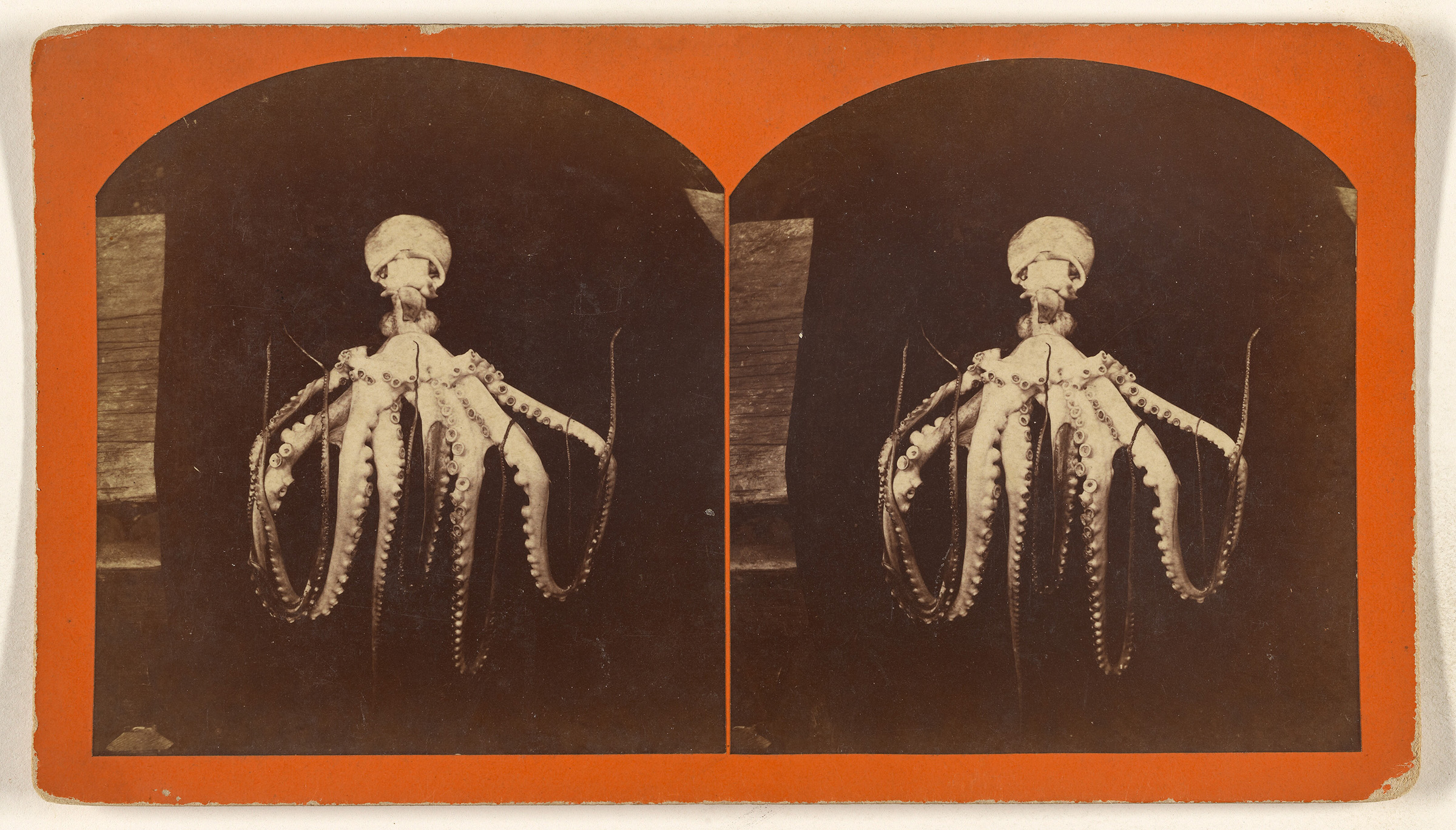

A difference between Jonathan birch and Shakyamuni Buddha is that Birch is not very concerned about killing animals. He’s worried about how farm animals, for example, would experience being raised and slaughtered, but he’s not against eating meat if it could be raised and slaughtered ethically. If it can’t be ethically farmed, he’s against it. For example, he thinks that octopuses cannot be raised ethically as livestock. So he’s for a ban of that. But he’s not against eating wild caught octopus, I think, if that could be done without pain. And honestly, this is a relief to me, because I do eat meat, I do kill mosquitos. Not causing undue suffering when I do that is something that I can aspire to. This is obviously incompatible with the First Precept. I took jukai in 2006 and I promised not to kill beings. I recognize the contradiction here, and I don’t have an answer to you for that. But avoiding causing suffering to sentient beings is something that I could aspire to.

A couple of years ago, due to Brexit, the United Kingdom was revising its animal welfare laws. It had withdrawn from the EU. And the EU had a treaty that said that animals are sentient beings, and member states must pay full regard to the welfare of animals. But the EU didn’t specify which animals are sentient or not. So I mean, technically, a brine shrimp is sentient. Do we have to worry about whether it experiences suffering or not? Unclear. When the UK replaced the European treaty with its own law, the first draft specified all invertebrates, so mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians. Some activists argued for the inclusion of two specific groups of invertebrates. These are cephalopods like octopuses, squids and cuttlefish, or decapods, like lobsters and crabs. So in comes our hero, Jonathan Birch. The UK hires him to lead a commission to study the possibility that cephalopods and decapods are sentient beings. And I don’t know how long it took them, years? They wrote a hundred-page document with 300 citations to research studies. And the upshot is that the big, smart cephalopods, like octopuses, are likely enough to be sentient that British legislature has to keep their welfare in mind, and the same for lobsters and crabs. Of course, the news reports are overblown. They say, UK declares lobsters are sentient beings, but it doesn’t mean that you’re going to be tried for murder if you eat a lobster in London. It just means that the UK legislature must consider their welfare when it passes future laws. That’s it.

But still, even though the impact of the sentience act of 2022 might be small, it’s an example of the widening moral circle, widening it to include more beings. The philosopher Peter Singer wrote about this. He said that the Expanding Circle is an example of moral progress, of society’s moral beliefs improving over time. He said,

The circle of altruism has broadened from the family and tribe to the nation and race, and we are beginning to recognize that our obligations extend to all human beings. The only justifiable stopping place for the expansion of altruism is the point at which all whose welfare can be affected by our actions are included within the circle of altruism.

Progress. Progress is a very modern concept, maybe the modern concept. Only once our technology and social change was happening rapidly enough that you could actually observe that change in one lifetime, did we start to think that progress, continuous improvement, was a trend that we could observe and expect to continue. And moral progress is this astonishingly modern idea, that there is some better morality. We don’t know yet what it is. We can only guess. There might be principles that are better, but we don’t know what they are, but we or our descendants in the future, will believe them and behave accordingly.

The idea makes me very uncomfortable, because it seems to indicate moral realism, or objective morality, that there is some moral truth that’s out there outside of our current beliefs, and that society can either progress toward it or move away from it. Otherwise how is it possible to define whether a change in morality is moral progress or just moral change? I’m pretty sure that there is no moral truth, that societies just choose their axioms and try to reason logically from them, and that every philosopher who does this either comes up with axioms that logically lead to repugnant conclusions that offend our instincts, or that they lead to logical contradictions, generally both, and then we just try again and again, and it’s doomed.

Buddha taught, I think, that there is moral truth. That behaving in accord with the truth that we’re all interdependent, and in accord with the truth that all sentient beings want to be liberated from suffering, behaving in this way is essentially good. I mean, now that I say that, it sort of sounds reasonable. That as long as there are sentient beings in the universe, and it’s true that we’re not separate, that it makes sense for us to try to help each other all achieve what we want. And what we want naturally is not to suffer, kind of by the definition of suffering. So maybe, if there is a moral truth, he was right. Nagarjuna wrote that the precepts are empty, that they have no essential nature, they’re skillful means, and that they’re useful so long as they match our circumstances. That also sounds right to me. But then how do you define useful or not useful? Skillful or not skillful? This is all very ambiguous to me.

But if moral progress is real and it involves less suffering for sentient beings, then moral progress is happening now and and it’s happening extremely rapidly. Over 1000 companies have pledged not to use meat or eggs from caged chickens in the US. Forty percent of hens are now cage free, and that was only 6% a decade ago. Starting last year, McDonald’s, all the chicken meat and eggs that it uses come from cage free hens, and that’s two years sooner than McDonald’s had promised.

Male chicks are generally useless to agriculture, and so in the past, they were generally handed sexed and then ground up alive. Now it’s technologically possible to sex them in ovo and destroy them before they’re hatched. So in my opinion, this is less suffering. This is morally superior, and this affects billions of chicks every year.

The UK’s largest grocery chains will stop selling live lobsters and crabs in their stores, so you don’t see those miserable lobsters in a tank there anymore. France’s largest producer of trout will now stun them unconscious before killing them, before slaughtering them. Germany’s largest grocery stores have cut the price of fake plant-based meat so that it’s equal to the price of animal meat. And this price cut led to a 30% increase in the sales of fake meat.

Billions of sentient beings every year are affected by these changes, and there’s just a ton of momentum happening right now to accelerate moral progress when it comes to animal welfare in agriculture. So as bodhisattvas, we should rejoice that all of these beings are suffering less. One of the vows of the Bodhisattva Samantabadhra in the Avatamsaka Sutra, was to “rejoice in the merit and virtues of others.” So let’s rejoice that people are caring about animal welfare and doing this research and making these promises and making these changes, instead of feeling guilty that we’re not doing enough, or discouraged because there’s still so much suffering in the world. A bodhisattva’s attitude is joy that we’re all moving in the right direction.

Of course, we can also find ways to do our individual part and to keep pushing in the right direction. We can be selective in what animal products we buy some of the grocery store. Labels really make a difference. Free range fowl, chicken etcetera, meat and eggs really is a meaningful label. It’s regulated by the USDA. Other animals, not so much, but it makes a difference for chickens. And then there are non government organizations that have more rigorous standards, and you can look for their certifications on animal products at the grocery store too. Obviously, eating less meat is better. The Farm Animal Welfare Program at Open Philanthropy is an effective activist and research group.

Mostly, I just want you to know that even though there’s a lot of grim news and a lot of ways in which humanity is going in the wrong direction, This is something where we’re seeing a lot of progress right now, and it’s something to keep an eye on and to rejoice in.

Image sources: