Why Should Async Get All The Love?: Advanced Control Flow With Threads

I spoke at PyCon 2022 about writing safe, elegant concurrent Python with threads. Here’s the video. Sorry about the choppy audio, the A/V at PyCon this year was a shitshow. Below is a written version of the talk.

asyncio.

Asyncio is really hip. And not just asyncio—the older async frameworks like Twisted and Tornado, and more recent ones like Trio and Curio are hip, too. I think they deserve to be! I’m a big fan. I spent a lot of time contributing to Tornado and asyncio some years ago. My very first PyCon talk, in 2014, was called “What Is Async, How Does It Work, And When Should I Use It?” I was an early async booster.

Asyncio introduced a lot of Pythonistas to advanced control flows with Tasks, Futures, chaining, asyncio.gather, and so on. All this was really exciting! But there’s something a lot of Python programmers didn’t notice at the time: All this was already possible with threads, too.

Threads.

Compared to asyncio, threads seem hopelessly outdated. The cool kids will laugh at you if you use threads.

Concurrency and parallelism #

Threads and asyncio are two ways to achieve concurrency.

Let’s avoid any confusion at the start: Concurrency is not parallelism. Parallelism is when your program executes code on multiple CPUs at once. Python mostly can’t do parallelism due to the Global Interpreter Lock. You can understand the GIL with a phrase short enough to fit on your hand: One thread runs Python, while N others sleep or await I/O. Learn more about the GIL from my PyCon talk a few years ago.

So threads and asyncio have the same limitation: Neither threads nor asyncio Tasks can use multiple CPUs.

(An aside about multiprocessing, just so you know I know what you’re thinking: If you really need parallelism, use multiprocessing. That’s the only way to run Python code using multiple CPUs at once with standard Python. But coordinating and exchanging data among Python processes is much harder than with threads, only do this if you really have to.)

But in this article I’m not talking about parallelism, I’m talking about concurrency. Concurrency is dealing with events in partial order: your program is waiting for several things to happen, and they could occur in one of several sequences. By far the most important example is waiting for data on many network connections at once. Some network clients and most network servers have to support concurrency, sometimes very high concurrency. We can use threads or an async framework, such as asyncio, as our method of supporting concurrency.

Threads vs. asyncio #

Memory #

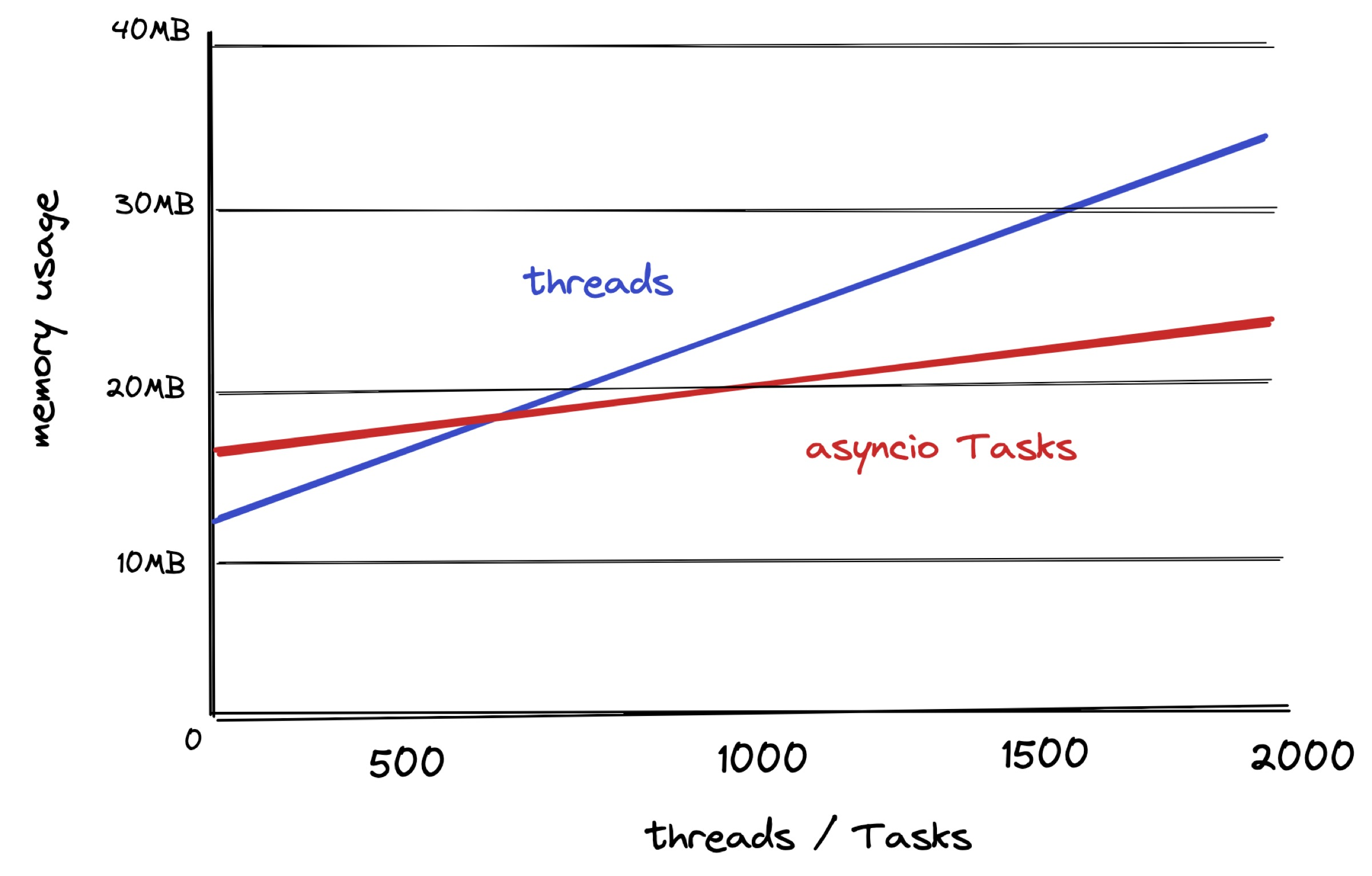

Which one should you use, threads or asyncio? Let’s start with asyncio’s main advantage: Very very high concurrency programs are more memory efficient with asyncio.

Here’s a chart of two simple programs spawning lots of threads (blue) and asyncio Tasks (red). Just importing asyncio means the red program starts with a higher memory footprint, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is, as concurrency increases, the red asyncio program’s memory grows slower.

A Python thread costs about 10k of memory. That’s not much memory! More than a few hundred threads is impractical in Python, and the operating system imposes limits that prevent huge numbers of threads. But if you have low hundreds, you don’t need asyncio. Threads work great. If you remember the problems David Beazley pointed out in Python 2, they were solved in Python 3.

With asyncio, each Task costs about 2k of memory, and there’s effectively no upper bound. So asyncio is more memory-efficient for very high concurrency, e.g. waiting for network events on a huge number of mostly idle connections.

Speed #

Is asyncio faster than threads? No. As Cal Peterson wrote:

Sadly async is not go-faster-stripes for the Python interpreter.

Under realistic conditions asynchronous web frameworks are slightly worse throughput and much worse latency variance.

Standard library asyncio is definitely slower than most multi-threaded frameworks, because asyncio executes a lot of Python for each event. Generally frameworks are faster the more that they’re implemented in C or another compiled language. Even with the fastest async frameworks, like those based on uvloop, tail latency seems to be worse than with multi-threading.

I’m not going to say all async frameworks are definitely slower than threads. What I can say confidently is that asyncio isn’t faster, and it’s more efficient only for huge numbers of mostly idle connections. And only for that.

Compatibility #

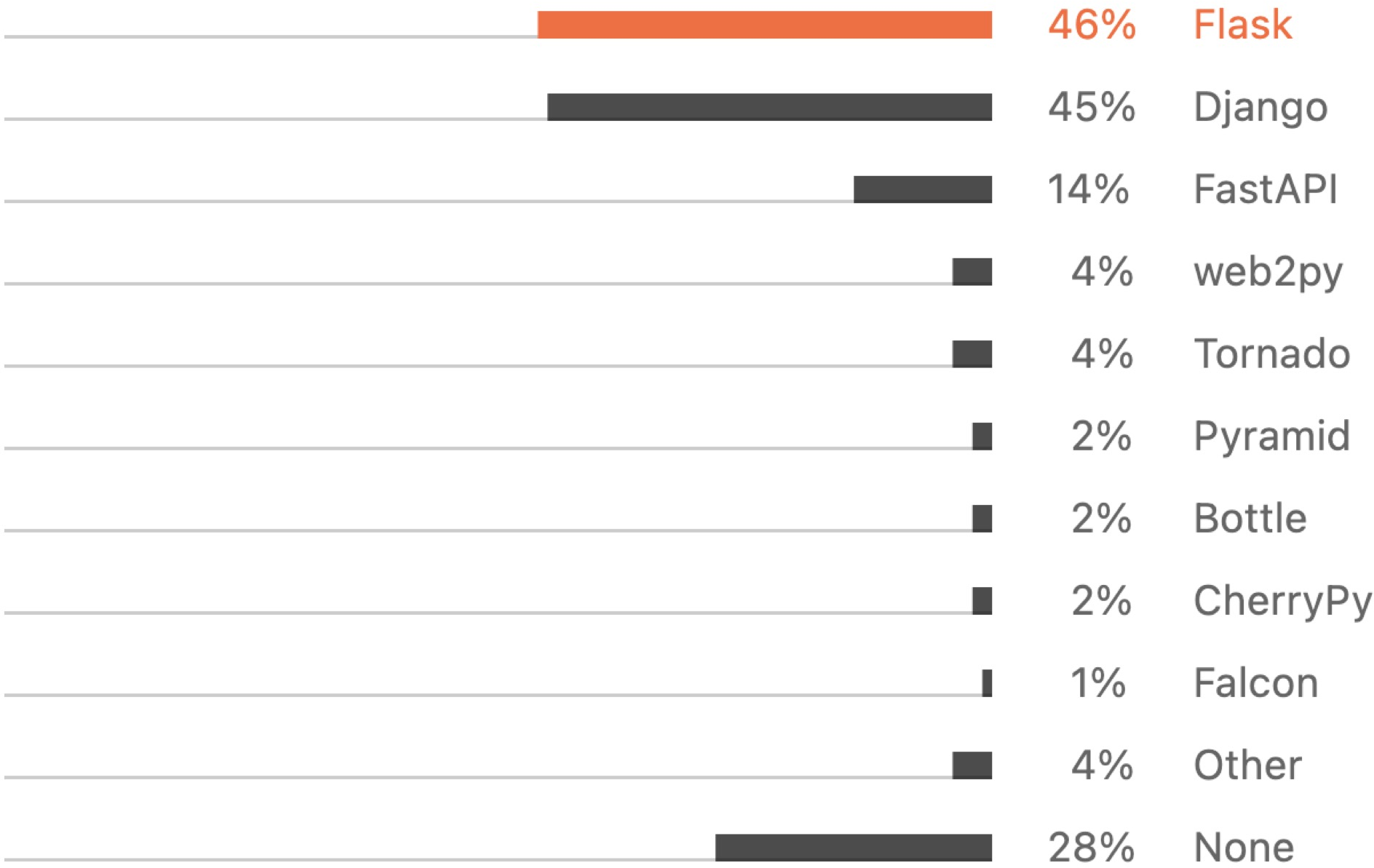

What about compatibility? Here are the most popular Python web frameworks (source).

The sum is more than 100% because respondents could choose multiple. Flask, Django, and most of the others are multi-threaded frameworks. Only three (FastAPI, Falcon, and Tornado) are asyncio-compatible. (We don’t know about the “other” category, but it’s only 4%.)

So your web application is probably multi-threaded now, not async. If you want to use asyncio, that means rewriting a large portion of your app. Whereas multi-threaded code is compatible with most of the apps, libraries, and frameworks already written.

Trickiness #

How tricky is it to write correct concurrent code with threads or asyncio?

Let’s make a function called do_something which adds one to a global counter, and run it on two threads at once.

counter = 0

def do_something():

global counter

print("doing something....")

counter += 1 # Not atomic!

t0 = threading.Thread(target=do_something)

t1 = threading.Thread(target=do_something)

t0.start()

t1.start()

t0.join()

t1.join()

print(f"Counter: {counter}")

Will counter always eventually equal 2? No! Plus-equals isn’t atomic. It first loads the value from the global, then adds 1, then stores the value to the global. If the two threads interleave during this process, one of their updates could be lost, and we end up with counter equal to 1, not 2.

We need to protect the plus-equals with a lock:

counter = 0

lock = threading.Lock()

def do_something():

global counter

print("doing something....")

with lock:

counter += 1

This is tricky! In a 2014 blog post Glyph Lefkowitz, the author of Twisted, talks about this trickiness. It’s still my favorite argument on the topic.

As we know, threads are a bad idea, (for most purposes). Threads make local reasoning difficult, and local reasoning is perhaps the most important thing in software development.

Glyph says the main reason to write async code isn’t that it’s faster. It’s not even memory efficiency. It’s that it’s less prone to concurrency bugs and it requires less tricky programming. (But it doesn’t have to be that bad, as you’ll see below.)

Let’s rewrite our counter-incrementing example with asyncio.

counter = 0

async def do_something():

global counter

print("doing something....")

await call_some_coroutine()

counter += 1 # Atomic! No "await" in +=.

async def main():

t0 = asyncio.Task(do_something())

t1 = asyncio.Task(do_something())

Now do_something is a coroutine. It calls another coroutine for the sake of illustration, and then increments the counter. We run it on two Tasks at once. Just by looking at the code we know where interleaving is possible. If it has an await expression, a coroutine can interleave there. Otherwise it’s atomic. That’s “local reasoning”. Plus-equals has no await expression, so it’s atomic. We don’t need a lock here.

Therefore asyncio is better than multi-threading, because it’s less tricky, right? We shall see….

In summary:

| Threads | asyncio |

| Speed: Threads are at least as fast. | Memory: asyncio efficiently waits on huge numbers of mostly-idle network connections. |

| Compatibility: Threads work with Flask, Django, etc., without rewriting your app for asyncio. | Trickiness: asyncio is less error-prone than threads. |

Must multi-threaded code be so tricky?

It’s Time To Take Another Look At Threads #

All along, it’s been possible to write elegant, correct code with threads. To begin, let’s look at how to use threads with Futures. Threads had Futures first, before asyncio. Futures let us express control flows you’d struggle to write with mutexes and condition variables.

(Confusingly, asyncio introduced a new Future class that’s different from the one we use with threads. I’ve never had to use both in the same program, so it’s fine.)

Future.

Let’s rewrite our previous counter-incrementing example with Futures.

from concurrent.futures import Future

future0 = Future()

future1 = Future()

def do_something(future):

print("doing something....")

future.set_result(1) # How much to increment the counter.

t0 = threading.Thread(target=do_something, args=(future0,))

t1 = threading.Thread(target=do_something, args=(future1,))

t0.start()

t1.start()

# Blocks until another thread calls Future.set_result().

counter = future0.result() + future1.result()

print(f"Counter: {counter}")

The concurrent.futures module is where all the cool threads stuff lives. It was introduced back in Python 3.2.

Now do_something takes a Future and sets its result to 1. This is called “resolving the Future”.

We run the function on two threads and pass in the two Futures as arguments. Then we wait for the threads to call set_result, and sum the two results. Calling Future.result() blocks until the future is resolved. Note that we no longer need to call Thread.join().

This code isn’t much of an improvement. I’m just showing how Futures work. In reality you’d write something more like this:

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

executor = ThreadPoolExecutor()

# Takes a dummy argument.

def do_something(_):

print("doing something....")

return 1

# Like builtin "map" but concurrent.

counter = sum(executor.map(do_something, range(2)))

print(f"Counter: {counter}")

We create a ThreadPoolExecutor, which runs code on threads and reuses threads efficiently. executor.map is like the builtin map function, but it calls the function concurrently over all the arguments at once. In this case do_something doesn’t need an argument, so we use a dummy argument list, range(2).

There’s no more explicit Futures or threads here, they’re hidden inside the implementation of map. I think this looks really nice, and not error-prone at all.

Workflows #

What about more complex workflows?

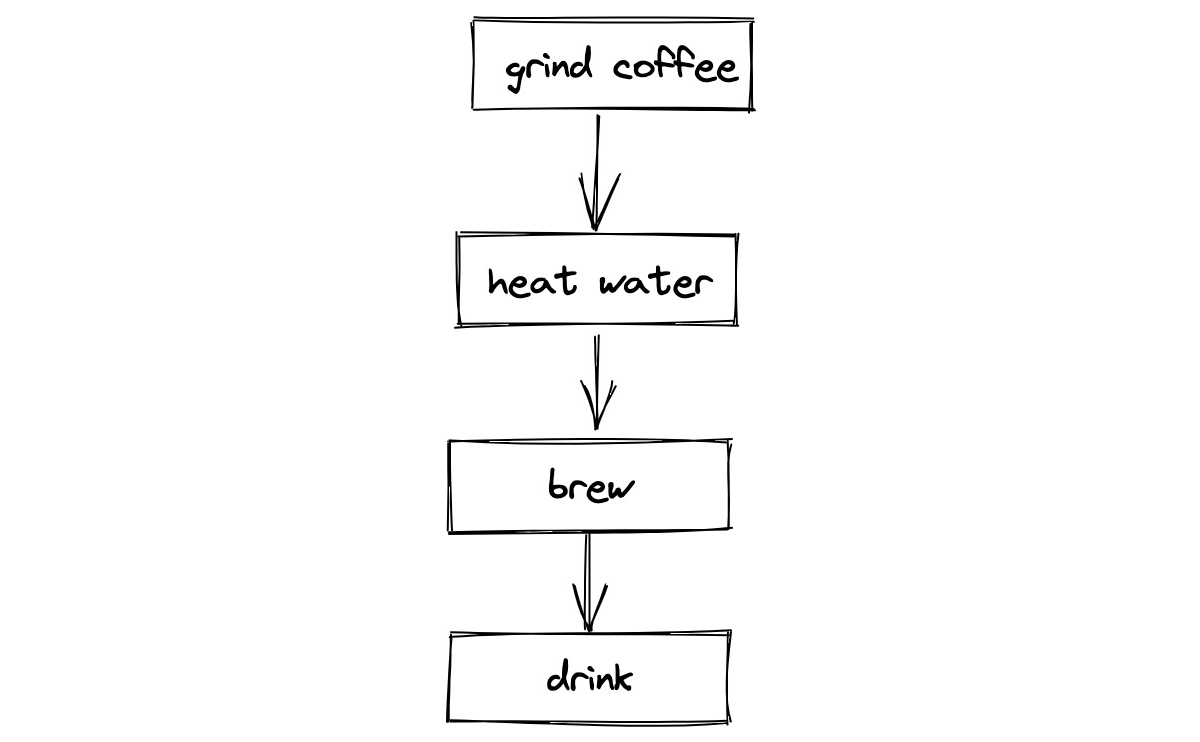

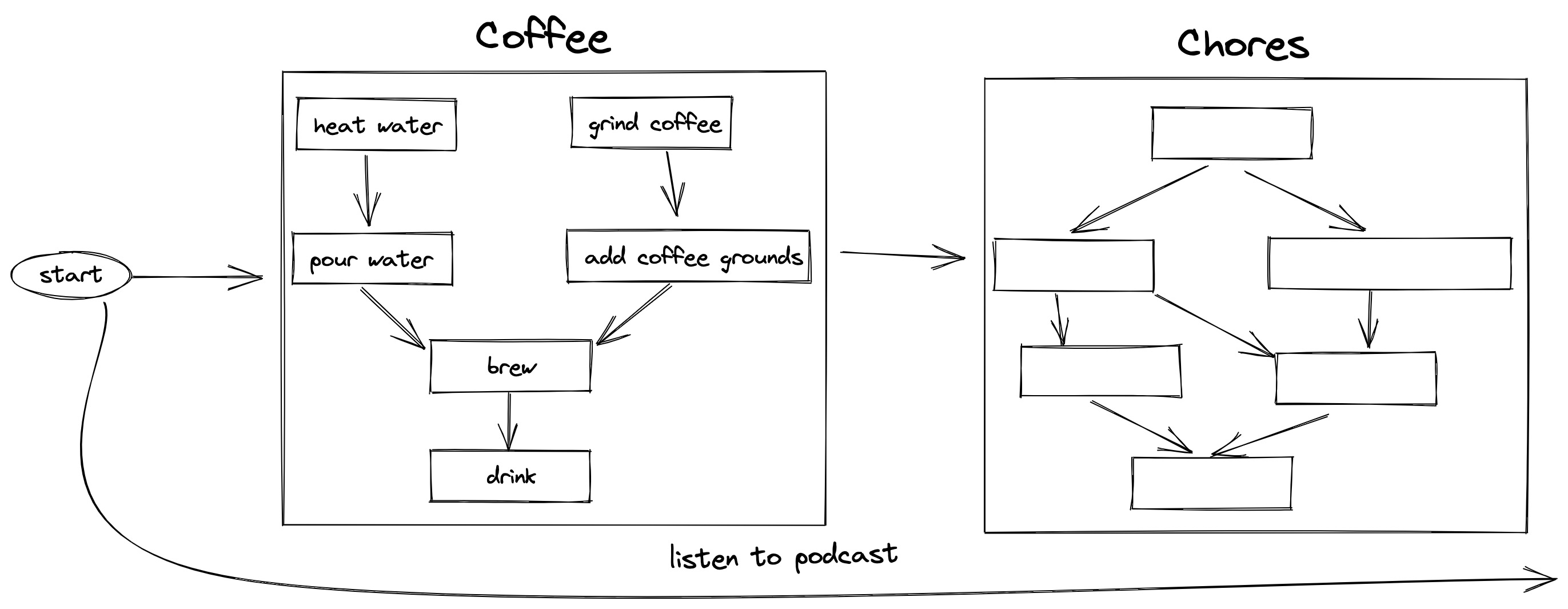

The morning before I gave this talk in Salt Lake City, I made French press coffee in my Airbnb. I brought a hand grinder, so grinding the coffee took some time. Then I heated water, combined them and waited for it to brew, and drank it.

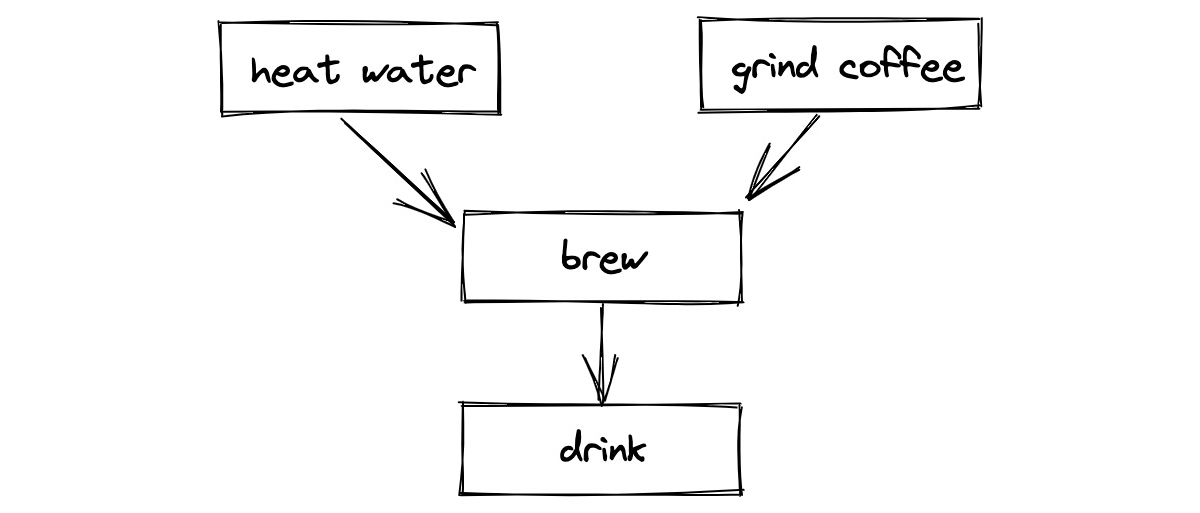

Obviously that’s not efficient. I should start the water heating and grind the coffee concurrently.

How can we code this with threads?

executor = ThreadPoolExecutor()

def heat_water():

...

def grind_coffee():

...

def brew(future1, future2):

future1.result()

future2.result()

time.sleep(4 * 60) # Brew for 4 minutes.

heated_future = executor.submit(heat_water)

ground_future = executor.submit(grind_coffee)

brew(heated_future, ground_future)

print("Drinking coffee")

The brew function takes two Futures and waits until both have completed, then waits for the coffee to brew. We use the ThreadPoolExecutor to start heating and grinding concurrently. We call brew and when it’s done, we can drink.

So far so good. Let’s add more steps to this workflow and see how this technique handles the added complexity.

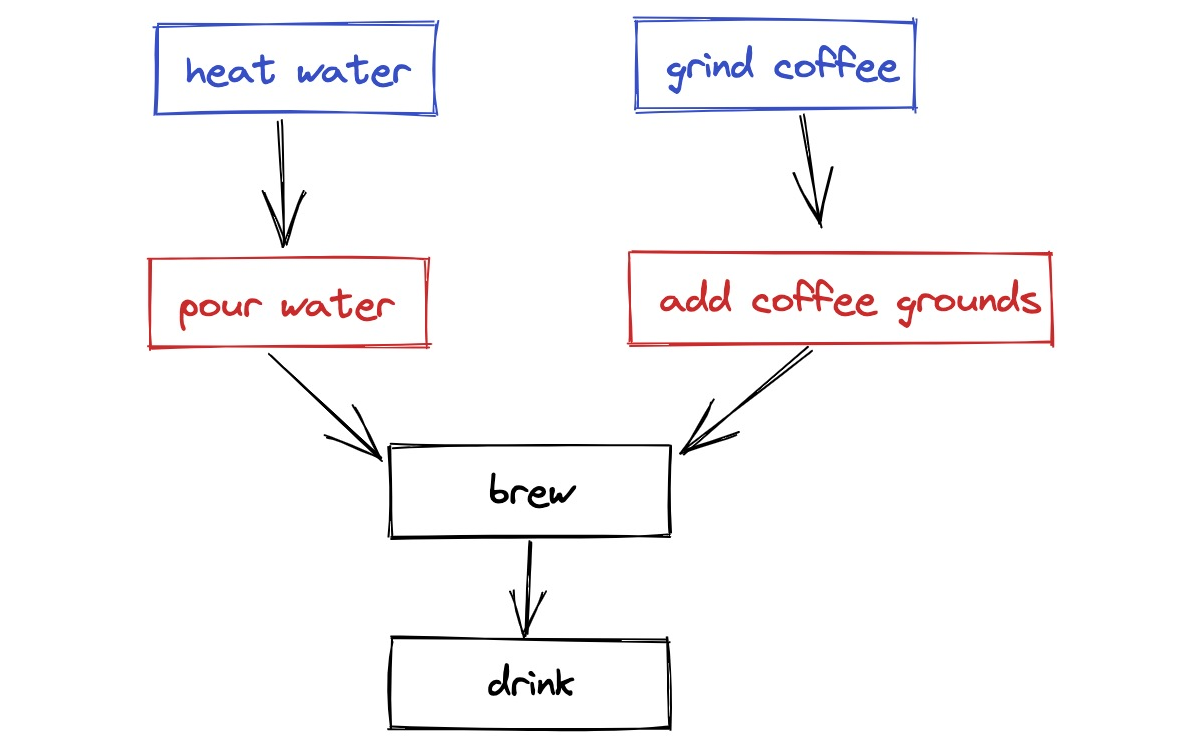

There’s a quick step right after heating the water: I pour it into the French press. And after I grind the coffee I add the grounds to the press. These events can happen in either order, but I always want to do the red step as soon as its blue step is completed.

def heat_water():

return "heated water"

def grind_coffee():

return "ground coffee"

def brew(future1, future2):

for future in as_completed([future1, future2]):

print(f"Adding {future.result()} to French press")

time.sleep(4 * 60) # Brew for 4 minutes.

Now the heat_water and grind_coffee functions have return values; they produce something. The new brew function uses as_completed, which is also in the concurrent.futures module. If the water is heated first, then we add it to the press, or if the coffee is ground first, we add the grounds first. Once both steps are done, then we wait 4 minutes. The rest of the code is like before.

Imagine if you had to use old-fashioned thread code, with locks and condition variables to signal when each step was done. It would be a nightmare. But with concurrent.futures the code is just as clean and easy as with asyncio.

Futures and Typing #

These code examples aren’t really modern Python yet, because they don’t have any types.

def heat_water() -> str:

return "heated water"

def grind_coffee() -> str:

return "ground coffee"

def brew(future1: Future[str], future2: Future[str]):

for future in as_completed([future1, future2]):

print(f"Adding {future.result()} to French press")

# ^ type system knows result() returns a string.

To use types with Futures, just subscript the Future type with whatever the Future resolves to, in this case a string. Then the type system knows that result() returns a string.

Workflows, Part 2 #

What if the “coffee” workflow is one component of a much larger workflow, encompassing a whole afternoon?

First I make and drink coffee, then I have the motivation to do chores, which is a separate complex workflow. Of course I’m listening to a podcast the whole time.

with ThreadPoolExecutor() as main_exec:

main_exec.submit(listen_to_podcast)

with ThreadPoolExecutor() as coffee_exec:

heated_future = coffee_exec.submit(heat_water)

ground_future = coffee_exec.submit(grind_coffee)

brew(heated_future, ground_future)

print("Drinking coffee")

# Join and shut down coffee_exec.

with ThreadPoolExecutor() as chores_exec:

...

# Join and shut down chores_exec.

# Join and shut down main_exec.

A nice way to structure nested workflows is using a with statement. I start a block like with ThreadPoolExecutor and run a function on that executor. I can start an inner executor using another with statement. When we leave the block, either normally with an exception, we automatically join and shut down the executor, so all threads started within the block must finish.

This style is called “structured concurrency”. It’s been popularized in several languages and frameworks; Nathaniel Smith’s Trio framework introduced it to a lot of Pythonistas, and it will be included in asyncio as “task groups” in Python 3.11.

Unfortunately we can’t do full structured concurrency with Python threads. Ideally, if one thread dies with an exception, other threads started in the same block would be quickly cancelled, and all exceptions thrown in the block would be grouped together and bubble up. But exceptions in ThreadPoolExecutor blocks don’t work well today, and cancellation with Python threads is Stone-Aged.

Cancellation #

Threads are not nearly as good at cancellation as asyncio, Trio, or other async frameworks. Here’s a handwritten solution; you’ll need something like this in your program if you want cancellation.

class ThreadCancelledError(BaseException):

pass

class CancellationToken:

is_cancelled = False

def check_cancelled(self):

if self.is_cancelled: raise ThreadCancelledError()

def do_something(token):

while True:

# Don't forget to call check_cancelled!

token.check_cancelled()

token = CancellationToken()

executor = ThreadPoolExecutor()

future = executor.submit(do_something, token)

time.sleep(1)

token.is_cancelled = True

try:

future.result() # Wait for do_something to notice that it's cancelled.

except ThreadCancelledError:

print("Thread cancelled")

The custom ThreadCancelledError inherits from BaseException rather than Exception, so that it bypasses most except blocks. Now in do_something we must add frequent calls to check_cancelled.

Python doesn’t control the thread scheduler the way it controls the asyncio event loop, so it’s not possible for thread cancellation to be as good. But it could be improved. See Nathaniel Smith’s 2018 article for superior ideas. I’m curious if anyone has a PEP for improving thread cancellation.

A Real Life Example #

Let’s get back to the good news about threads.

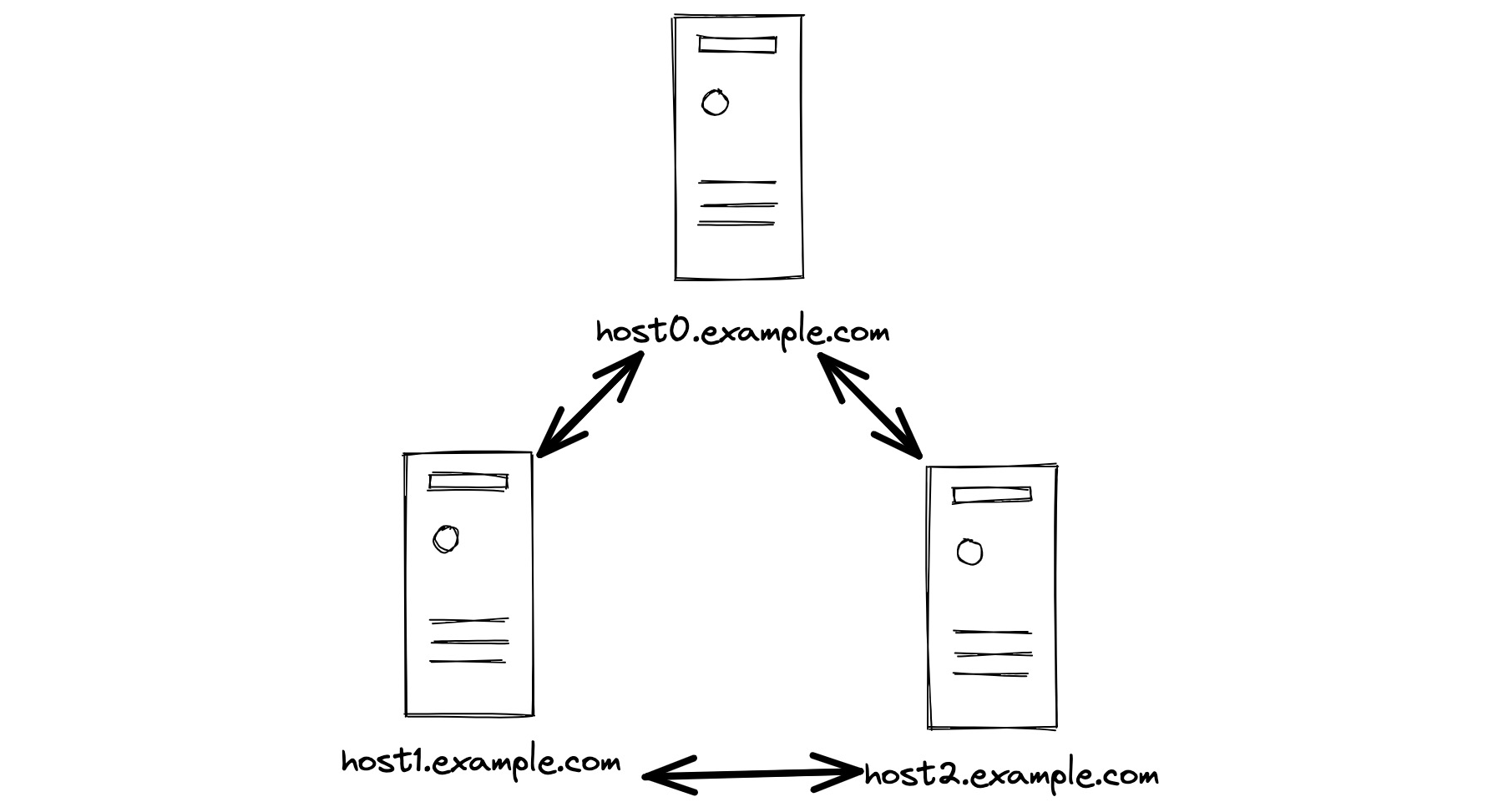

Here’s a real life example I coded a few months ago. I implemented Paxos in Python. Paxos is a way for a group of servers to cooperate for fault-tolerance. Here’s a group of three servers which all communicate with each other.

How does each server know all its peers’ names? Let’s give them all a config file.

{

"servers": [

"host0.example.com",

"host1.example.com",

"host2.example.com"

]

}

But how does any server know which one it is? This is surprisingly hard. In a data center or cloud deployment, each server usually has several IPs and several DNS names, such as its internal and external names. Calling gethostname() usually doesn’t give you the information you need. There’s no easy way to know if a DNS query for host0, for example, resolves to this server or another server.

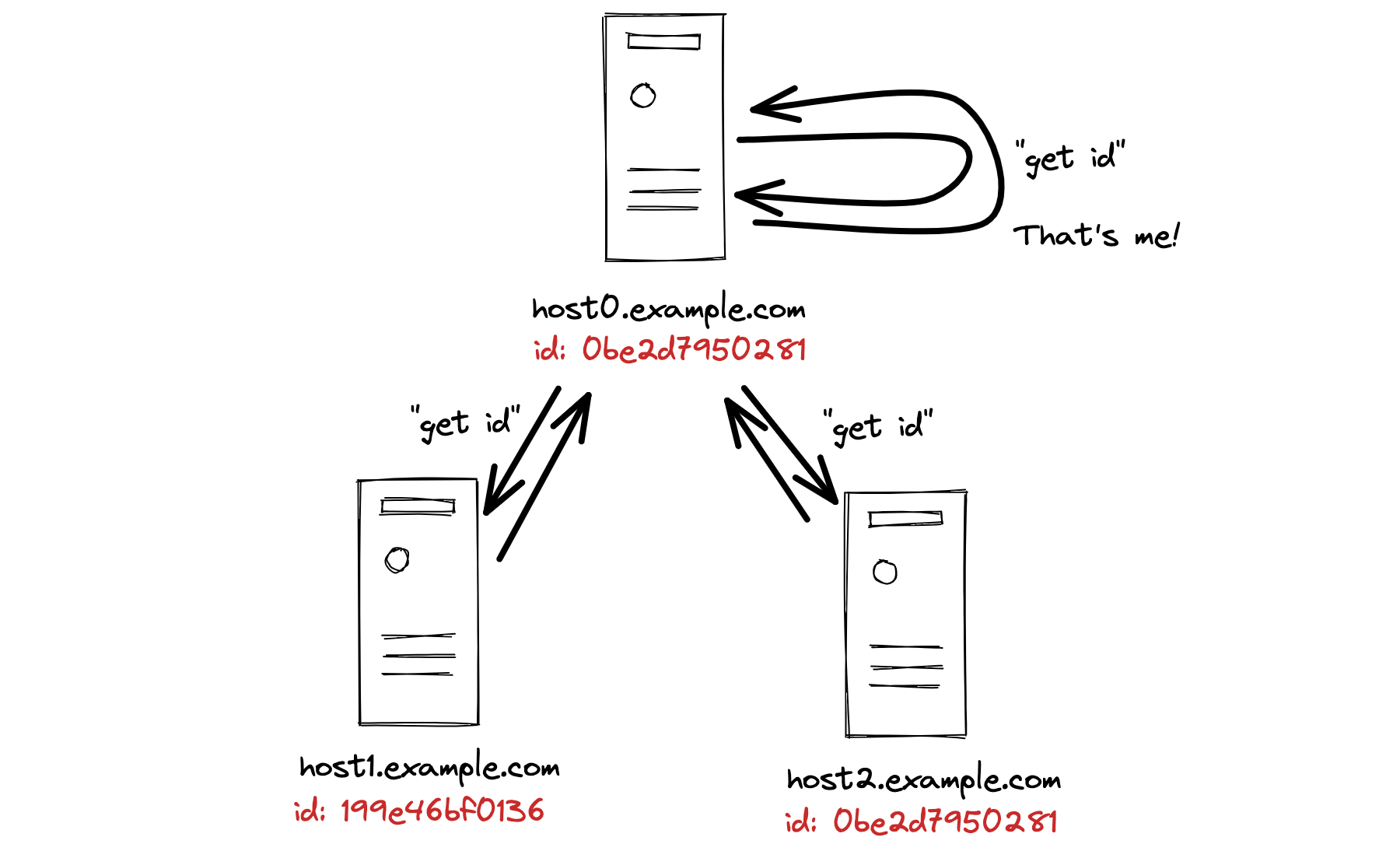

The solution is sort of amazing. First, each server generates a random unique id for itself when it starts up. Next, each server sends a request to all the servers in the list, which includes itself, but it doesn’t know which one is self. Here I show host0 sending out three requests; the others do the same. host0 gets replies from host1 and host2 with different ids, and it gets a reply from host0 with its own id! So it knows that it is host0.

This is actually how MongoDB and lots of other distributed systems solve this problem.

Servers can’t process any requests until they find themselves, and they can start up in any order, so this creates a complex control flow. Sounds like a job for Futures!

Here’s the server code. We’ll start by generating a unique id for this server. I want to use Flask for the server, of course—Flask is the most popular web framework. The server makes a Future which it will resolve when it finds itself.

server_id = uuid.uuid4().hex

app = flask.Flask('PyPaxos')

self_future = Future()

@app.route('/server_id', methods=['GET'])

def get_server_id():

return flask.jsonify(server_id)

@app.route('/client-request', methods=['POST'])

def client_request():

# Can't handle requests until I find myself, block here.

self_future.result()

...

config = json.load(open("paxos-config.json"))

executor = ThreadPoolExecutor()

# Run Flask server on a thread, so main thread can search for self.

app_done = executor.submit(app.run)

start = time.monotonic()

while time.monotonic() - start < 60 and not self_future.done():

for server_name in config["servers"]:

try:

# Use Requests to query /server_id handler, above.

reply = requests.get(f"http://{server_name}/server_id")

if reply.json() == server_id:

# Found self. Unblock threads in client_request()

# above, and exit loop.

self_future.set_result(server_name)

break

except requests.RequestException as exc:

# See explanation below.

pass

time.sleep(1)

app_done.result() # Let app run in background.

The server can’t process any client requests until it’s found itself, so client_request waits for self_future to be resolved by calling self_future.result(). Once the future has been resolved, calling result() always returns immediately.

The search loop tries repeatedly for a minute to find self, by querying for each server’s id. It might catch an exception when querying; either because it’s trying to reach another server that hasn’t started yet, or it’s trying to reach itself but Flask hasn’t initialized on its background thread.

After the search loop completes we wait for app_done.result(): that means the main thread sleeps until the server thread exits, maybe because of a Control-C or some other signal.

Clean and clear, right? If I had rewritten this with asyncio I couldn’t use Flask, the most popular web framework, and I couldn’t use Requests, the most popular client library. (Requests doesn’t support asyncio.) I would’ve had to rewrite everything to use asyncio. But with threads, I can implement this advanced control flow in a straightforward and legible manner, and I can still use Flask and Requests.

Cool Threads #

Threads are cool. Don’t let the asyncio kids make you feel like a nerd.

Threads are a better choice than asyncio for most concurrent programs. They’re at least as fast as asyncio, they’re compatible with the popular frameworks, and with the techniques we looked at, using Futures and ThreadPoolExecutors, multi-threaded code can be safe and elegant.