It Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time: PyMongo's "start_request"

The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

I'll tell you the story of four regrettable decisions we made when we designed PyMongo, the standard Python driver for MongoDB. Each of these decisions led to years of pain for PyMongo's maintainers, Bernie Hackett and me, and years of confusion for our users. This winter I'm ripping out these regrettable designs in preparation for PyMongo 3.0. As I delete them, I give each a bitter little eulogy.

Today I'll tell the story of the first regrettable decision: "requests".

The Beginning

It all began when MongoDB, Inc. was a tiny startup called 10gen. Back in the beginning, Eliot Horowitz and Dwight Merriman were making a hosted application platform, a bit like Google App Engine, but with Javascript as the programming language and a JSON-like database for storage. Customers wouldn't use the database directly. It would be exposed through a clean API.

Under the hood, it had a funny way of reporting errors. First you told the database to modify some data, then you asked it whether the modification had succeeded or not. In the Javascript shell, this looked something like:

> db.collection.insert({_id: 1})

> db.runCommand({getlasterror: 1}) // It worked.

{

"ok" : 1,

"err" : null

}

> db.collection.insert({_id: 1})

> db.runCommand({getlasterror: 1})

{

"ok" : 1,

"err" : "E11000 duplicate key error"

}The raw protocol was neatly packaged behind an API that handled error reporting for you. (Eliot describes the history of the protocol in more detail here.)

As 10gen grew, we realized the application platform wasn't going to take off. The real product was the database layer, MongoDB. 10gen decided to toss the application platform and focus on the database. We started writing drivers in several languages, including Python. That was the birth of PyMongo. Mike Dirolf began writing it in January of 2009.

At the time we thought our database's funky protocol was a feature: if you wanted minimum-latency writes, you could write to the database blind, without stopping to ask about errors. In Python, this looked like:

>>> # Obsolete code, don't use this!

>>> from pymongo import Connection

>>> c = Connection()

>>> collection = c.db.collection

>>> collection.insert({'_id': 1})

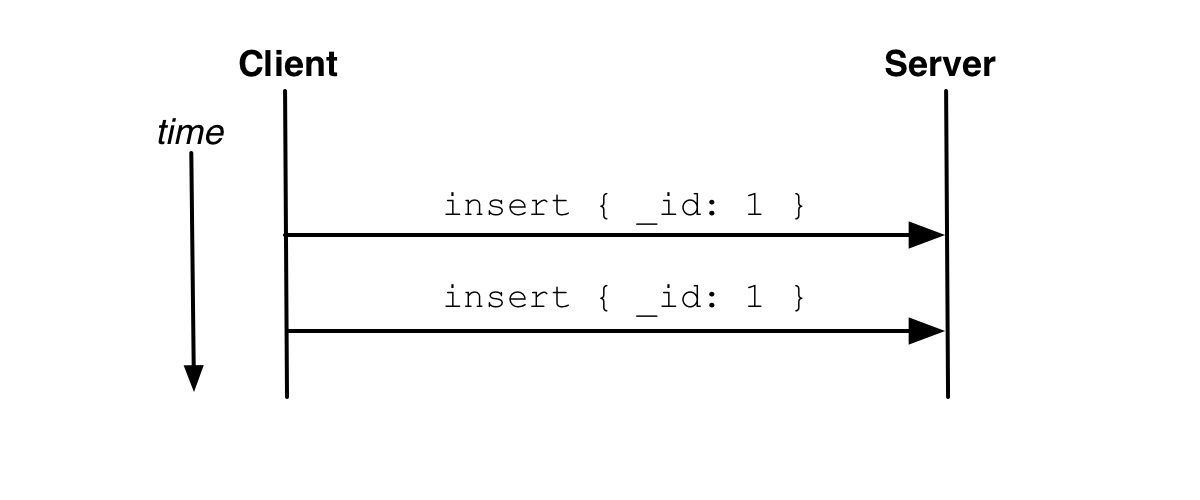

>>> collection.insert({'_id': 1})Unacknowledged writes didn't care about network latency, so they could saturate the network's throughput:

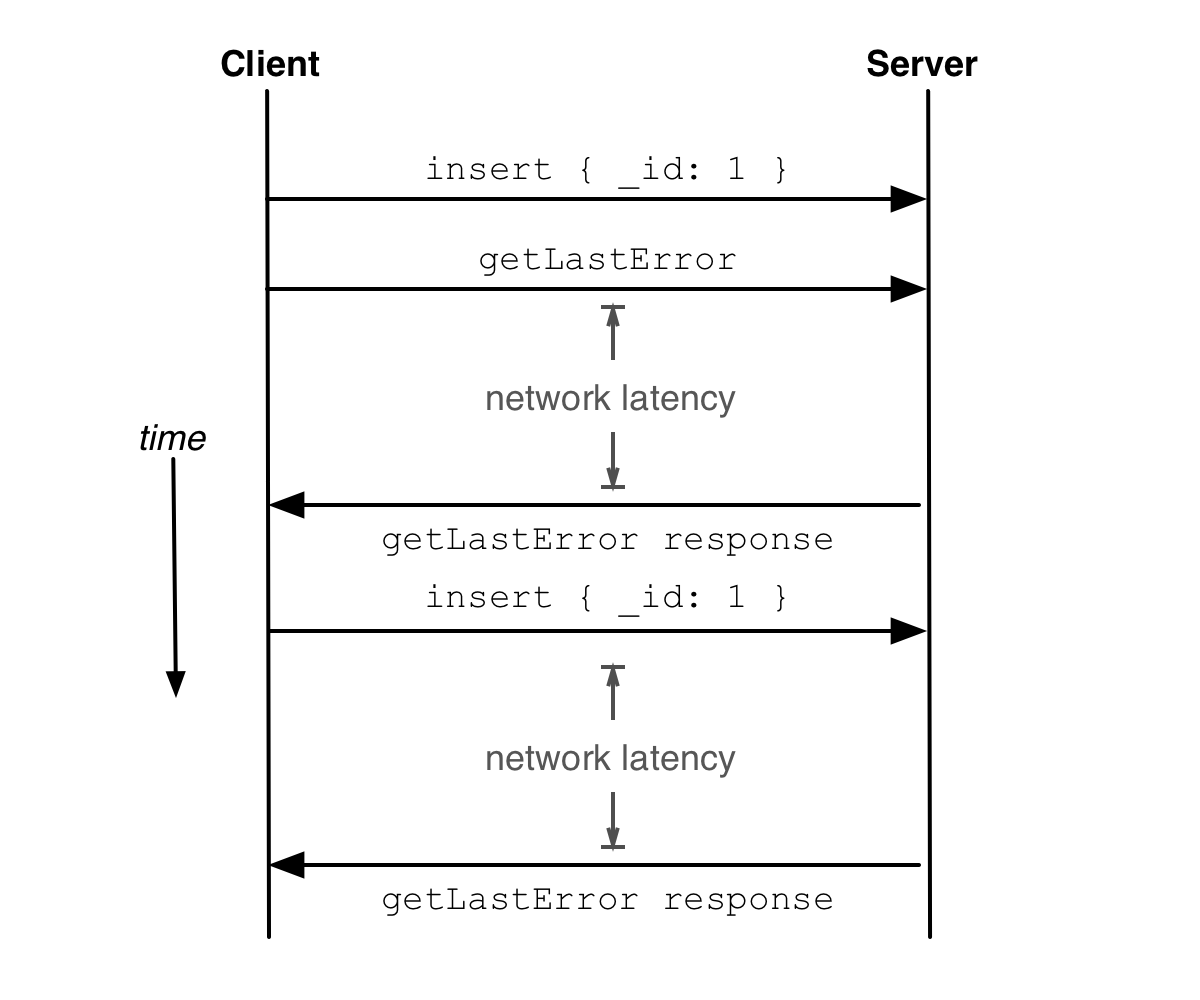

On the other hand, if you wanted acknowledged writes, you could ask after each operation whether it succeeded:

>>> # Also obsolete code. "safe" means "acknowledged".

>>> collection.insert({'_id': 1}, safe=True)

>>> collection.insert({'_id': 1}, safe=True)But you'd pay for the latency:

We thought this design was great! You, the user, get to choose whether to await acknowledgment, or "fire and forget." We made our first regrettable decision: we set the default to "fire and forget."

The Invention of start_request

There are a number of problems with the default, unacknowledged setting. The obvious one is, you don't know whether your writes succeeded. But there's a subtler problem, a problem with consistency. After an unacknowledged write, you can't always immediately read what you wrote. Say you had two Python threads executing two functions, doing unacknowledged writes:

c = Connection()

collection_one = c.db.collection_one

collection_two = c.db.collection_two

def function_one():

for i in range(100):

collection_one.insert({'fieldname': i})

print collection_one.count()

def function_two():

for i in range(100):

collection_two.insert({'fieldname': i})

print collection_two.count()

threading.Thread(target=function_one).start()

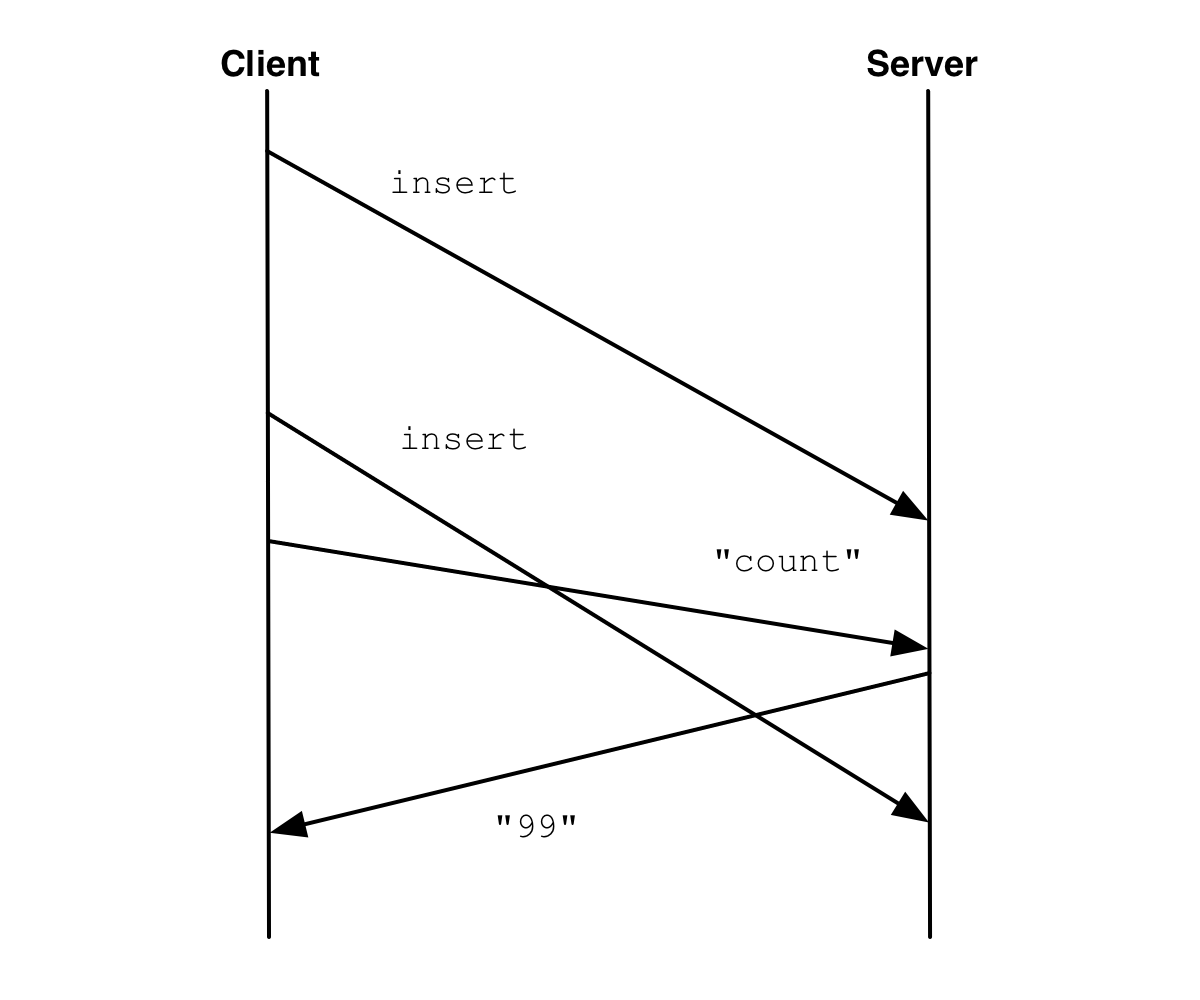

threading.Thread(target=function_two).start()Since there are two threads doing concurrent operations, PyMongo opens two sockets. Sometimes, one thread finishes sending documents on a socket, checks the socket into the connection pool, and checks the other socket out of the pool to execute the "count". If that happens, the server might not finish reading the final inserts from the first socket before it responds to the "count" request on the other socket. Thus the count is less than 100:

If the driver did acknowledged writes by default, it would await the server's acknowledgment of the inserts before it ran the "count", so there's no consistency problem.

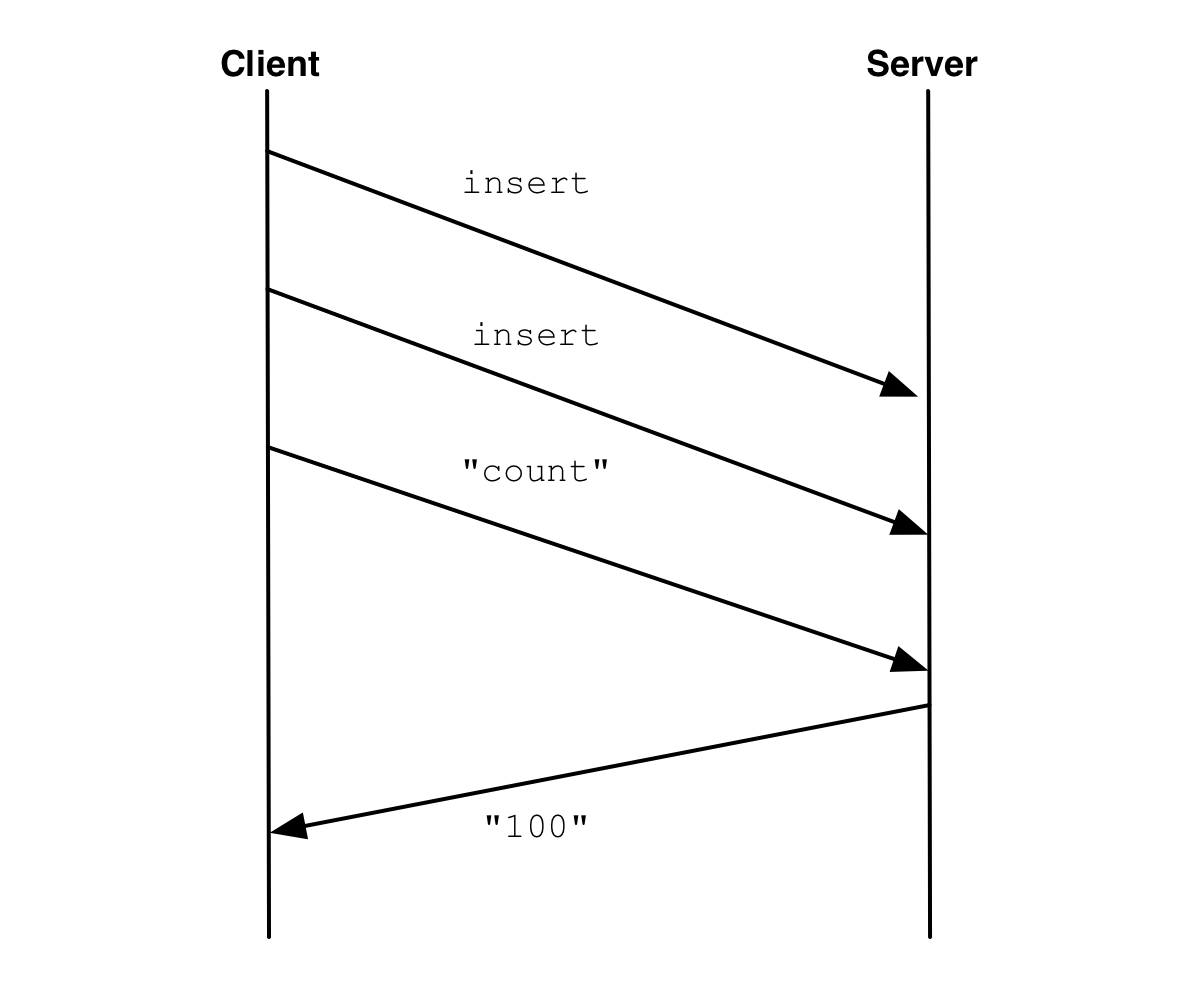

But the default was unacknowledged, so users would get results that surprised them. In January of 2009, PyMongo's original author Mike Dirolf fixed this problem. He wrote a connection pool that simply allocated a socket per thread. As long as a thread always uses the same socket, it doesn't matter if its writes are acknowledged or not:

The server doesn't read the "count" request from the socket until it's processed all the inserts, so the count is always correct. (Assuming the inserts succeeded.) Problem solved!

Whenever a new thread started talking to MongoDB, PyMongo opened a new socket for it. When the thread died, its socket was closed. Mike's solution was simple and did what users expected. And thus began PyMongo's five-year trudge down the road to hell.

I don't want you to misunderstand me: What Mike did seemed like a good idea at the time. The company had decided that unacknowledged was the default setting for all MongoDB drivers, but Mike still wanted to guarantee read-your-writes consistency if possible. Plus, the Java driver already associated sockets with threads, so Mike wanted the Python driver to act similarly.

I can picture Mike sitting at one of the desks in 10gen's original office. There were only a half-dozen people working for 10gen then, or fewer. This was long before my time. They had a corner of an office shared by Gilt, ShopWiki and Panther Express, in an old gray stone building on 20th Street in Manhattan, next to a library. It would've been very cold that day, maybe snowy. I see Mike sitting next to Eliot, Dwight, and their tiny company. He was banging out a Python driver for MongoDB, making one quick decision after another. Did he know he was setting a course that could not be corrected for five years? Probably not.

So Mike had decided that PyMongo would reserve a socket for each thread. But what if a thread talks to MongoDB, and then goes and does something else for a long time? PyMongo reserves a socket for the thread, that no one else can use. So in February, Mike added the "end_request" method to let a thread relinquish its socket. He also added an "auto_start_request" option. It was turned on by default, but you could turn it off if you didn't need it. If you only did acknowledged writes, or if you didn't immediately read your own writes, you could turn off "auto_start_request" and you'd have a more efficient connection pool.

The next year, in January 2010, Mike simplified the pool. In his new code, "auto_start_request" could no longer be turned off. His commit message claimed he made PyMongo "~2x faster for simple benchmarks." He wrote,

Calling Connection.end_request allows the socket to be returned to the pool, and to be used by other threads instead of creating a new socket. Judicious use of this method is important for applications with many threads or with long running threads that make few calls to PyMongo.

Bernie Hackett took over PyMongo the year after that, and since "auto_start_request" didn't do anything any more, Bernie removed it entirely in April 2011.

The "judicious use of end_request" tip had been in PyMongo's documentation since the year before, but Bernie suspected that users didn't follow the directions. Just as most people don't recycle their plastic bottles, most developers didn't call "end_request", so good sockets were wasted. Even worse, since threads kept their sockets open and reserved for as long as each thread lived, it was common to see a Python application deployment with thousands and thousands of open connections to MongoDB, even though only a few connections were doing any work.

Therefore, when I came to work for Bernie that November, he directed me to improve PyMongo's connection pool in two ways. First, PyMongo should once again allow you to turn off "auto_start_request". Second, if a thread died without calling "end_request", PyMongo should somehow detect that the thread had died and reclaim its socket for the pool, instead of closing it.

Making "auto_start_request" optional again was easy. If you turned it off, each thread just checked its socket back into the pool whenever it wasn't using it. When the thread next needed a socket, it checked one out, probably a different one. We recommended that PyMongo users do "safe" writes (that is, acknowledged writes), and turn off "auto_start_request". This led to better error reporting and much more efficient connection pooling: sane choices but not, alas, the defaults. We couldn't change the defaults because we had to be backwards-compatible with the regrettable decisions made years earlier.

So restoring "auto_start_request" was a cinch. Detecting that a thread had died, however, was hell.

The Road to Hell

I wanted to fix PyMongo so it could "reclaim" sockets. If a thread had a socket reserved for it, and it forgot to call "end_request" before it died, PyMongo shouldn't just close the socket. It should check the socket back into the connection pool for some future thread to use. My first solution was to wrap each socket in an object with a __del__ method:

class SocketInfo(object):

def __init__(self, pool, sock):

self.pool = pool

self.sock = sock

def __del__(self):

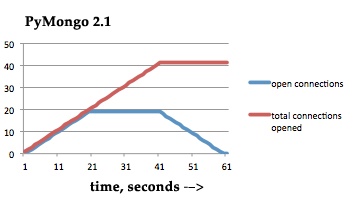

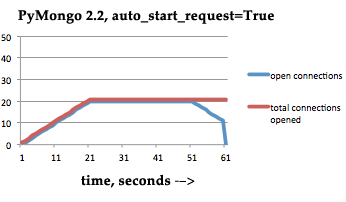

self.pool.return_socket(self.sock)Piece of cake. We released this code in May 2012, and it was much more efficient. Whereas the previous version of PyMongo's pool tended to close and open sockets frequently:

PyMongo 2.2 reclaimed dead threads' sockets for new threads that wanted them:

I was proud of my achievement. Then all hell broke loose.

The worst bug

Right after we released my "socket reclamation" code in PyMongo, a user reported that in Python 2.6 and mod_wsgi 2.8, and with "auto_start_request" turned on (the default), his application leaked a connection once every two requests! Once he'd leaked a few thousand connections he ran out of file descriptors and crashed. It took me 18 days of desperate debugging, with Dan Crosta by my side, before I got to the bottom of it. It turns out there are roughly three bugs in Python's threadlocal implementation, which were all fixed when Antoine Pitrou rewrote threadlocals for Python 2.7.1. One of them was reported and the other two never were.

The unreported bug I'd found was in the C function in the Python interpreter that manages threadlocals. By accessing a threadlocal from a __del__ method, I'd caused the function to be called recursively, which it wasn't designed for. This caused a refleak every second time it happened, leaving open sockets that could never be garbage-collected.

This bug in an obsolete version of Python was, in turn, interacting with an obsolete version of mod_wsgi, which cleared each Python thread's state after each HTTP request. So anyone on Python 2.7 or mod_wsgi 3.x, or both, wouldn't hit the bug. But ancient versions of Python and mod_wsgi are widely used.

I wrote up my diagnosis of the bug, reimplemented my socket reclamation code to avoid the recursive call, and released the fix. I wrote a frustrated article about how weird Python's threadlocals are, and early the next year I wrote a description of my workaround.

To this day, the bug is my worst. It's among the worst for impact, certainly it was the hardest to diagnose, and it remains the most complicated to explain.

That last point—the bug is hard to explain—has real costs. It makes it very hard for anyone but me to maintain PyMongo's connection pool. Anyone else who touches it risks recreating the bug. Of course, we test for the bug after every commit: we loadtest PyMongo with Apache and mod_wsgi in our Jenkins server to guard against a regression of this bug. But no outside contributor is likely to go to such effort, nor to understand why it is necessary.

A bug factory

A full year later, in April 2013, I discovered another connection leak. Unlike the 2012 bug, this leak was rare and hard to reproduce. I don't think anyone was hurt by it. I was a much better diagnostician by now, and I knew the relevant part of CPython all too well. It took me less than a day to determine that in Python 2.6, assigning to a threadlocal is not thread safe. I added a lock around the assignment and released yet another bugfix for "start_request" in PyMongo.

For my whole career at MongoDB, I've regularly found and fixed bugs in "start_request". In 2012 I found that if one thread calls "start_request", other threads can sometimes think, wrongly, that they're in a request, too. And when a replica set primary steps down, threads in requests all threw an exception before reconnecting.

In 2013 a contributor Justin Patrin tried to add a feature to our connection pool, but what should have been a straightforward patch got fouled by the barbed wire in "start_request". In his code, if a thread in a request got a network error it leaked a semaphore. And just last month I had to fix a little bug in the connection pool related to "start_request" and mod_wsgi.

An attractive nuisance

There's another thing about "start_request" that's almost as bad as its complexity: its name. It's an attractive nuisance. It sounds like, "I have to call this before I start a request to MongoDB." I frequently see developers who are new to PyMongo write code like this:

# Don't do this.

c.start_request()

doc = c.db.collection.find_one()

c.end_request()This is completely pointless, a waste of the programmer's effort and the machine's. But the name is so vague, and the explanation is so complex, you'd be forgiven for thinking this is how you're supposed to use PyMongo.

Now, I ask you, which decision was the most regrettable? Was socket reclamation a bad feature—should we have let PyMongo continue closing threads' sockets when threads died, instead of building a Rube Goldberg device to check those sockets back into the pool? Or maybe a worse idea came years before, when Mike turned on "auto_start_request" by default—maybe everything would have been okay if he'd required users to call "start_request" explicitly, instead. Maybe he shouldn't have implemented "start_request" at all. Most likely, the root cause was the decision we made before Mike even started writing PyMongo: the decision to make unacknowledged writes the default.

Redemption

MongoClient

Late in 2012, while I was in the midst of all these "start_request" bugs, Eliot had an idea that turned us around, and showed us the way back from hell. He figured out a way redeem our original sin, the sin of making unacknowledged writes the default. See, we had long recommended that users override PyMongo's defaults, like so:

>>> # Obsolete.

>>> c = Connection(safe=True, auto_start_request=False)...but we couldn't make this the new default because it would break backwards compatibility. Eliot decided that all the drivers should introduce a new class with the proper defaults. Scott Hernandez came up with a good name for the class, one that no driver used yet: "MongoClient".

>>> # Modern code.

>>> c = MongoClient()While we were at it, we deprecated the old "safe / unsafe" terms and introduced a new terminology, "write concern". Users could opt into the new class, but we wouldn't break any existing code. Orpheus took the first step of his walk home from Hades.

Write commands

In MongoDB 2.6, released this spring, we began to undo an even older decision: the old protocol that sends a modification to MongoDB, then calls "getLastError" to find out if it succeeded. The new protocol, write commands, always awaits a response from the server. Furthermore, it lets us batch hundreds of modifications in a single command, and get a batch of responses back. The change was transparent to users, but we transcended the tradeoff of our original protocol. You no longer have to decide if you want low-latency unacknowledged writes, or acknowledged writes and pay for the latency. Now you can batch up your operations, do acknowledged writes, and get the best of both worlds.