Say Useful Things To An Audience That's Listening: 6 Tips For Delivering A PyCon Talk

Sylvia Pankhurst didn't waste time on Q & A.

Ten minutes before my first PyCon talk ever, I was standing at the podium. I had got up there as soon as the previous speaker stepped off—I had to be sure I was ready in time for my 3:15pm slot! The nice session runner gave me a water bottle, the A/V guy wired me up, and then they left me to stand and sweat at the lectern. I stared at the audience as they filed in. The waiting was unbearable. At the moment my laptop's clock flipped from 3:14 to 3:15, I began.

It turns out that starting on time was a terrible idea.

In my brief career as a public speaker since this talk, I've developed a useful principle: When you're onstage, say useful things to an audience that's listening. Otherwise, be offstage. Stage-manage the talk so that this is never violated.

A Harrowing Trial

Because I started my talk at 3:15 on the dot, the audience wasn't listening yet. For the first five minutes, the bulk of them were still arriving, climbing over each other's knees to get to inner seats, rummaging in their laptop bags. Worse, it biased the audience to sit in the back: people always want to sit in the back anyway, but that day they especially didn't want to travel to the front while I was talking. This left me isolated onstage, beyond a moat of empty front rows.

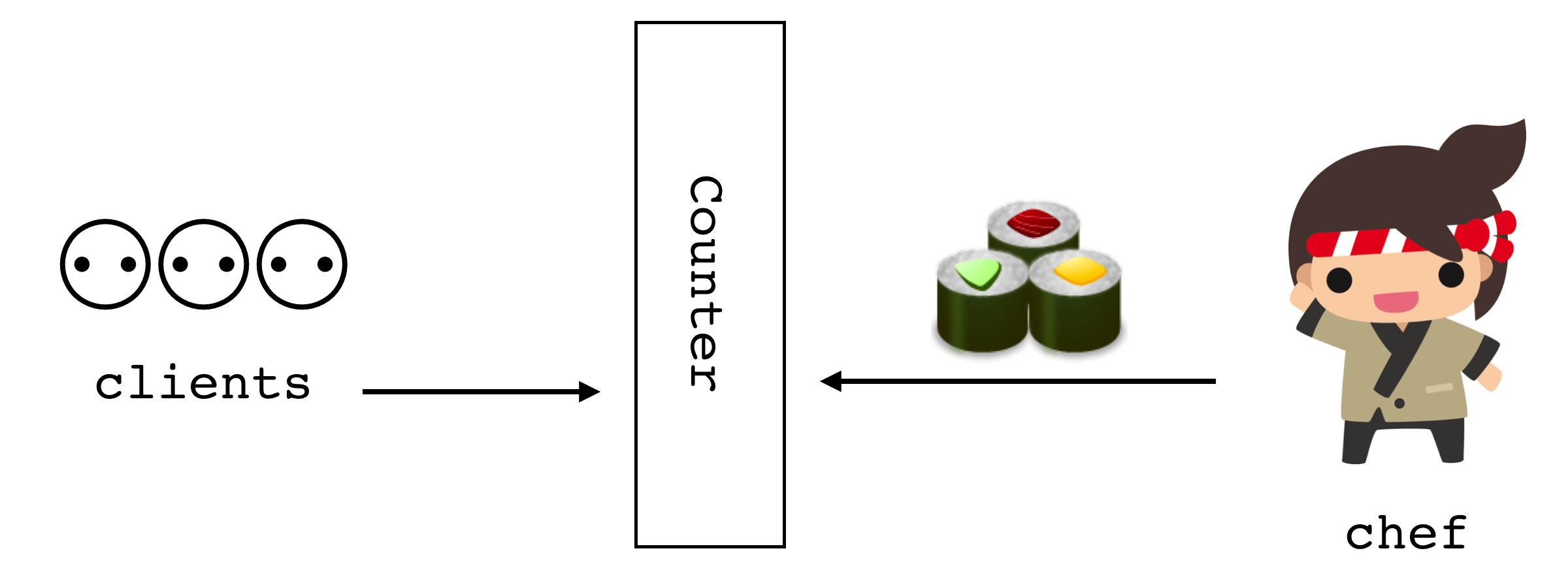

Once the audience settled in, the middle acts of my talk went fine. My silly analogy that async code works like a sushi chef got some laughs, especially when I showed my slides.

What really saved me, though, were the two audience members who'd chosen the front row: Sumana Harihareswara and my girlfriend Jennifer Armstrong. Sitting together right in front of me, they led the laugh track and assured me I was OK. I concluded strong and asked for questions. That was when my momentum fell into the dirt.

A man with a strong accent came to the microphone and asked a question that I could not, for the life of me, understand. He wanted advice on...making async applications? Dogging async application? (Jennifer told me later she was trying, psychically, to communicate it to me: "He's asking about debugging async applications!")

This situation is terrible: I'm embarrassed I can't understand, I'm worried that he's embarrassed that he can't be understood, and yet we can't give up in front of everyone. Luckily I heard him on his third try: "Debugging! You want to know about debugging," I gasped. "I have no idea how to debug async applications. You should...think really hard?"

After that, the Q & A session digressed into a debate over how I'd implemented Motor, my async MongoDB driver. This was interesting, but not what the audience had come for.

What had I learned from my rocky debut? Given my current principle, "onstage, say useful things to an audience that's listening," what would I have done differently in 2014?

Start Late

Recently my speaking coach Melissa Collom told me that a "Broadway Start" is 7 minutes late. I wish I'd known that in 2014. I wouldn't have started speaking while everyone was jostling around in the back of the auditorium.

Starting late is a way to shift the balance of power. At 3:15 sharp, I was begging the audience to settle down and listen to me. If I'd waited just a few minutes, the audience would've been eager for me to start. A PyCon start isn't 7 minutes, perhaps it's 2 or 3 minutes. It's certainly more than zero. Losing those minutes is worth the cost—what's the value of a minute of speaking if no one's listening, anyway?

There's a syllogism I want the audience to accept: They are listening whenever I'm onstage. I'm onstage now, therefore they are listening.

Never lost the audience's attention.

Starting at 3:15 led them to exactly the wrong conclusion, because when I first opened my mouth they weren't paying attention at all.

Don't Introduce Yourself

A corollary to my principle is: Don't introduce yourself.

When you introduce yourself, your first words are something like, "Hello, let's start now." You're beginning to speak before the audience is listening.

Big conferences like PyCon have session chairs to introduce you, but you can ask the organizer to introduce you, even at a small Meetup. Force that person to be the Bad Cop who asks everyone be quiet. You're the Good Cop who comes in afterward, and gives the audience something interesting to listen to. You ensure you are never onstage unless you are saying something useful and the audience is paying attention.

Make an Entrance

Burst into the room with enthusiasm.

I like to sit in the front row with the session chair making smalltalk until a few minutes after my start time. This keeps me offstage, honoring my principle, and it keeps the session chair, who's chomping at the bit, from starting too soon. We're both anxious to begin, but we can calm ourselves with chitchat.

At one or two minutes past the start time, I am more or less holding down my session chair. At three minutes, I let the session chair go onstage, ask for the audience's attention, and introduce me. Only then do I spring onstage like Johnny Carson and deliver the first line of my talk.

Eye Contact

Looked at the audience, not her slide deck.

I use a remote clicker and I aim to memorize my slides sufficiently that I rarely look at the big screen. The Keynote "presenter view" on my laptop shows my speaker notes and the slide that's coming next, but instead of looking at it I prefer to stand in the middle of the stage and talk to the audience.

If I go a bit off script, great. Going off script is being alive.

Couldn't take his eyes off his notes.

No Questions, Please

Once you've delivered your compelling half-hour speech and inspired the audience with a call to action, what happens next? A few minutes of random questions?

Speakers feel obliged to take questions, as if we were politicians with a duty to the public, or academics who must defend our results. But at a conference we're not politicians or academics: we're putting on a show.

Question Time is a bad show. No matter how well the talk went, it's ruined, more often than not, by the cringeful Q & A. Why would you spend your final minutes onstage this way? Instead, you could spend it delivering a couple more valuable ideas for the audience, and end on a high note, never relinquishing control of the presentation until it's over.

Didn't let a little person distract from her topic.

Melissa Collom pointed out to me that not doing Q & A in public actually encourages people to connect with you: they'll have to come talk with you in the hallway or by email. It will be a much more valuable conversation than the gladiatorial Q & A at the microphone.

But If We Must Do Q & A

If Q & A can't be avoided, Melissa taught me a few more tips to make the best of it.

First, it is crucial to end your main talk with "thank you very much." This tells the audience the talk is over and they should clap. (The next time you see a speaker not do this, witness the awkwardness. Now do you see why it's important to say "thank you" and wait for applause?) As the clapping fades, announce you have time for a few questions.

Be brisk in the Q & A. The worst sound is a person on stage asking, "Are there any more questions? Anyone?" If there's even a few seconds pause, finish it. Remember, the audience showed up to hear your talk, not the verbiage they'll retch up when you implore them to think of questions. Quit while you're ahead.

The Bonus Track

Do you remember, on cassette tapes, that bands would hide a bonus track at the end of the album? After the final listed song, there'd be minutes of hissy silence and then something extra, an experimental or funny song not listed on the box.

You're going to do the same trick. And no matter how badly the Q & A goes, you'll still finish on a high note.

When you run out of time or questions, whichever comes first, show a final slide and deliver a second finale. Yes, this requires forethought. But it's worth the effort: after enduring several uncomfortable and digressive questions from the audience (bless their hearts), it's crucial to regain control at the end. "Thanks for your questions. Remember, go to this link to learn more, and always remember that fairies fear iron!" ....or whatever your core message is.

My point is, devote your final seconds onstage to refocusing the audience on the thesis you want them to remember. Then say "thank you" once again so the audience applauds again. Now we know the show is over.

Images:

- Sylvia Pankhurst advocating for women's suffrage in Trafalgar Square, 1908.

- The Great Poet, J. J. Grandville, 1867.

- George Edwards Hering, "La corbeille", 1850.

- Old Book Illustrations.

- Oslo Davis cartoon, "Time For Just One".

- Aimé de Lemud, "Three Women and Child", 1844.