Paper Review: C5: Cloned Concurrency Control that Always Keeps Up

C5: Cloned Concurrency Control that Always Keeps Up, by Jeffrey Helt, Abhinav Sharma, Daniel J. Abadi, Wyatt Lloyd, Jose M. Faleiro, in VLDB 2022. The authors describe a useful optimization for primary-backup replication, but they don’t break new ground. Here’s a video presentation I made to the DistSys Reading Group about this paper, and my written review below.

I don’t have images of clones or anything apropos, but it’s snowing in New Paltz, NY so I’ll try to entertain you with snowy images.

Background #

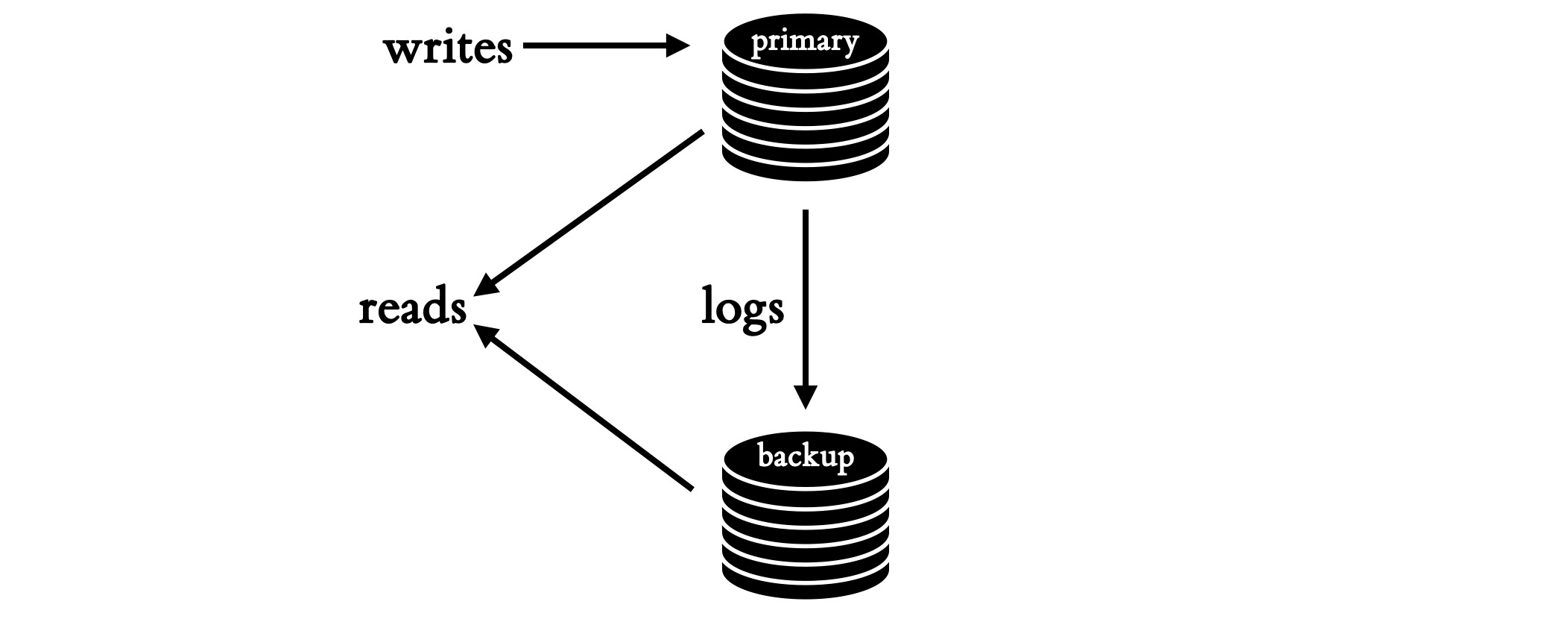

First let’s review some background—quickly, since it’ll be familiar to distributed databases people. This paper is about asynchronous replication, meaning you can write to the primary and the backups will replicate the writes eventually.

MongoDB and many other Raft- or Paxos-like systems work this way. Note that in asynchronous replication, the primary applies the write to its local data immediately, and then the write is replicated by the backup.

Multiple clients can write to the primary at once, but the primary’s copy of the data reflects some serial ordering of the writes. In the examples in this paper, the primary executes multi-row transactions and seems to guarantee serializability: every transaction appears to commit at an instant in time. Thus reads from the primary show the result of some serial order of committed transactions. But the point of this paper isn’t serializability: whatever guarantee the primary makes about reads, the backup eventually must, too.

The primary logs all its writes in the order they were executed, and streams the logs to the backup. The backup applies the writes to its own copy of the data. Clients can read from the backup. The authors want the backup to guarantee “monotonic prefix consistency”, meaning that clients see “a progressing sequence of the primary’s recent states”; each state reflects a complete prefix of the primary’s log. To ensure this, the backup implements a “cloned concurrency control” protocol.

The Problems #

C5 addresses two problems:

- High parallelism on the primary, low parallelism on the backup.

According to the authors, in many primary-backup systems, the backup executes writes with low parallelism; this is a bottleneck and causes replication lag. (I agree that replication lag is a common problem, but there are many causes, see below.) If the backup lags then reads will show stale data. Recent writes will be lost if the primary dies before they’re replicated. Worse, a backup can fall off the end of the log: If there’s a finite buffer of log entries (on the primary and/or the backup) and the backup lags so much that unreplicated entries are evicted, then the backup can never catch up. This usually requires manual recovery.

- Unconstrained parallelism on the backup would allow consistency violations.

But you can’t just permit a free-for-all among backup threads; if they apply log entries in a different order than the primary did, the backup’s copy of the data will permanently diverge.

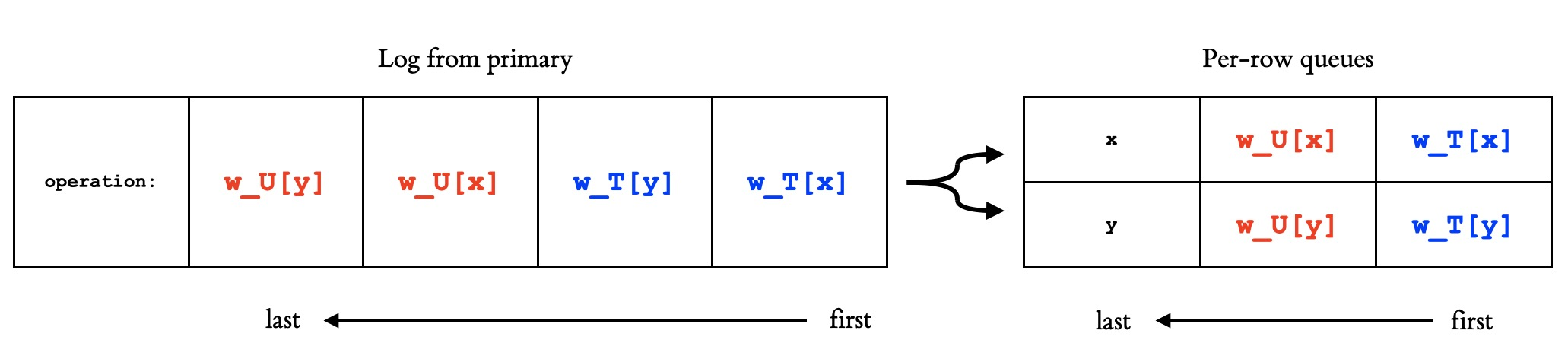

For instance, suppose two transactions T and U each update rows x and y . If different workers execute the resultant writes (denoted wT[x], wT[y], wU[x], and wU[y]), wT[x] may finish before wU[x] and wU[y] before wT[y]. If there are no further writes to these rows, the backup will forever reflect wU[x] and wT[y], violating transactional atomicity and thus monotonic prefix consistency.

The C5 Backup Algorithm #

The algorithm presented in the paper executes on the backup with the same degree of parallelism as on the primary, while guaranteeing monotonic prefix consistency. Here’s an example, with the transactions T and U from before:

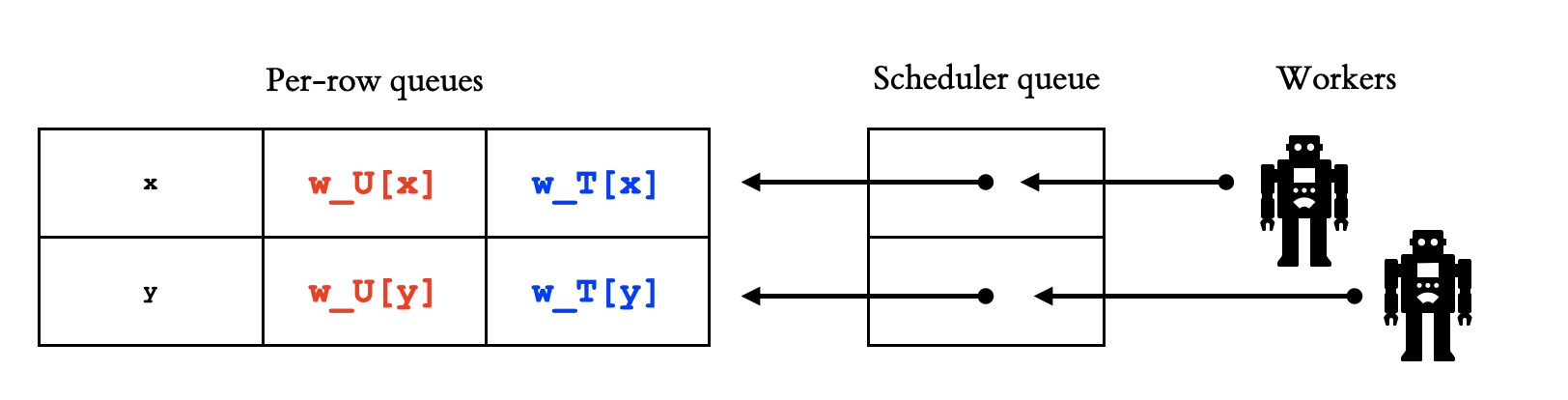

The backup receives a log of writes from the primary, in the order the primary executed them. The backup has a queue per row, so x has a queue and y has a queue. The backup moves log entries in order from the log to the per-row queues.

There’s a scheduler queue with pointers to the per-row queues. Let’s say the backup has a thread pool with two workers. Each worker follows a pointer from the head of the scheduler queue to the head of a per-row queue and executes the write there. This schedule ensures that each row receives writes in the same order as on the primary, but there’s no order guarantee between rows, so you could still see inconsistencies if you read from the backup. How does C5 ensure monotonic prefix consistency for readers?

The C5 Snapshot Algorithm #

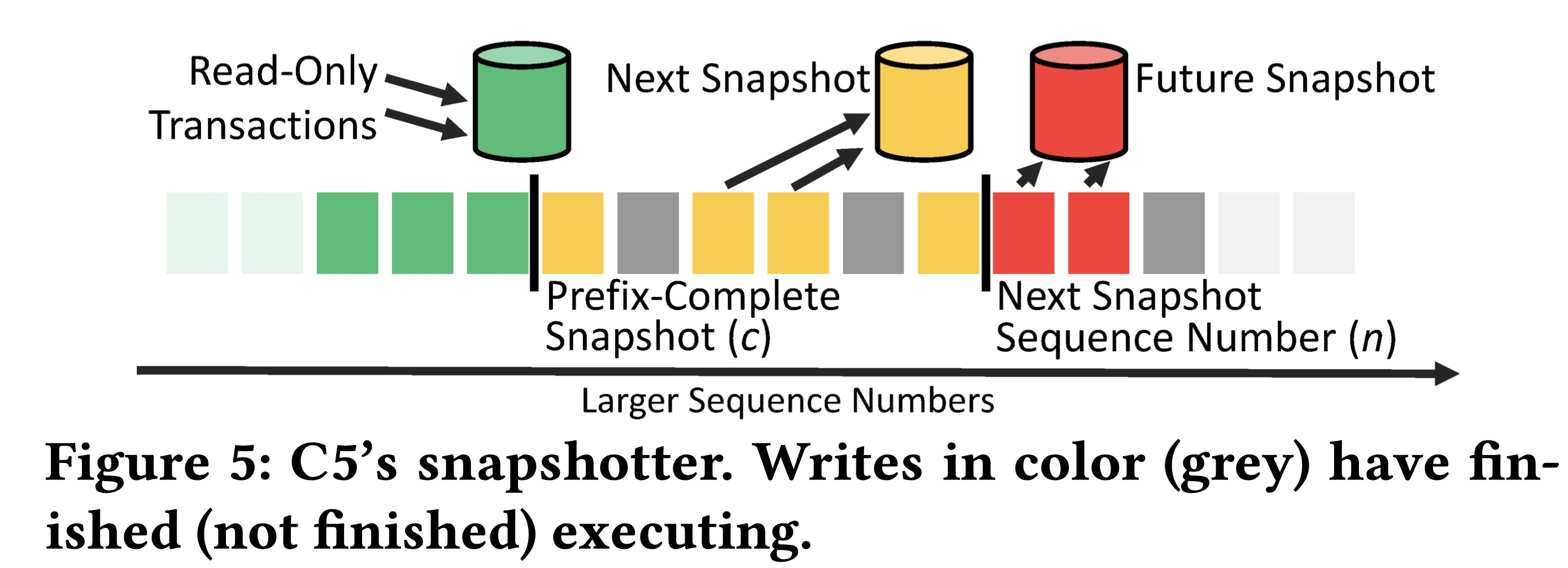

C5 assumes an MVCC storage layer with multiple snapshots. It maintains a “current” snapshot which is prefix-complete: all writes up to some log entry c are included, so clients can read from it. There is also a “next” snapshot which is being updated with log entries between c and n in parallel. Since the backup server executes writes out of order, “next” is inconsistent and hidden from readers. Finally there’s a “future” snapshot which is updated with log entries after n.

As soon as all the writes to the “next” snapshot are complete, next becomes current, future becomes next, a new future snapshot is started, and c and n are shifted to the right. Now reads come from the new “current” snapshot so they see newer data, but still prefix-consistent.

I think you could accomplish this with just two snapshots: “current” and “next”. The C5 authors seem concerned that snapshot installation takes time. They want to start writing to “future” while they install “next” and read from “current”, so they don’t lose availability during that time.

C5 Goals #

The authors have two goals. First, match the primary’s parallelism on the backups. They say “cloned concurrency control has commensurate constraints (C5) with the primary.” Second, preserve monotonic prefix consistency. It seems plausible that they’ve accomplished these with the scheduler and snapshotter described above.

The rest of the paper goes into details about two implementations of their algorithm. One of them was an improvement to the MyRocks database and the authors show that it solved a replication lag problem at Meta. The paper does not describe in detail what backup algorithm Meta ran before, and I didn’t research it. I’ll take them at their word that the previous algorithm’s low parallelism was culpable for Meta’s replication lag.

My Evaluation #

The C5 authors claim their scheduling algorithm is novel in 2022, but I’m pretty sure Eliot Horowitz implemented it in MongoDB in 2014:

Author: Eliot Horowitz <eliot@10gen.com>

Date: Fri Oct 31 11:28:37 2014 -0400

SERVER-15900: secondaries should stripe writes by doc if doc locking is on

uint32_t hash = 0;

MurmurHash3_x86_32( ns, len, 0, &hash);

+ const char* opType = it->getField( "op" ).value();

+

+ if (getGlobalEnvironment()->getGlobalStorageEngine()->supportsDocLocking() &&

+ isCrudOpType(opType)) {

+ BSONElement id;

+ switch (opType[0]) {

+ case 'u':

+ id = it->getField("o2").Obj()["_id"];

+ break;

+ case 'd':

+ case 'i':

+ id = it->getField("o").Obj()["_id"];

+ break;

+ }

+

+ size_t idHash = hashBSONElement( id );

+ boost::hash_combine(idHash, hash);

+ hash = idHash;

+ }

+

(*writerVectors)[hash % writerVectors->size()].push_back(*it);

This code runs on MongoDB secondaries. It takes a log entry iterator it and adds it to one of the worker queues in writerVectors. (MongoDB uses 16 workers for replication.) The code before Eliot’s change hashed the collection namespace ns and used that to choose a writer vector: that’s collection-level parallelism. But in MongoDB 3.0 we acquired WiredTiger and implemented document-level locking, so Eliot added code to get the document id and use that in the hash too. Voilà, document-level parallelism. This algorithm is identical to the C5 scheduler, or so nearly identical that only their parents can tell them apart.

Our snapshotter is also the same as C5’s, except we only need two snapshots, not three, because “installing” a snapshot with WiredTiger is instant: A secondary just updates the lastApplied timestamp after executing each batch of log entries, and secondary queries read at lastApplied by default, achieving monotonic prefix consistency avant la lettre. We introduced snapshot reads on secondaries in MongoDB 4.0 in 2018; before that, secondary reads blocked while the secondary applied a batch of log entries.

But I feel like a jerk for criticizing a paper as “not novel”. If there are systems that can improve their backup parallelism and haven’t yet, this paper is a good explanation of a useful optimization. In our experience at MongoDB, replication lag usually has other causes: the secondary’s network connection to the primary is slow, or the secondary is underpowered, or the primary is so overloaded it can’t send logs. But perhaps if we hadn’t already maximized replication parallelism then it would be a bottleneck. Evidently it was at Meta.

(Update, 2022-12-22: my colleague Kev Pulo recalls that when MongoDB replication was single-threaded, back in the day, it was a bottleneck. Collection-level parallelism was an improvement some time in the 2.x series, and presumably document-level parallelism was a further improvement for some users, starting in 3.0.)