After 244 Days Off

As planned, I returned from an 8-month leave and resumed work for MongoDB last week. My intention for the long break was to climb a lot, practice being afraid, get more comfortable on the wall, and have more fun climbing. My secondary goal was to read more computer science research and focus on learning, freed of daily engineering responsibilities. I accomplished the first goal and not the second, and I’m completely satisfied with that.

Climbing #

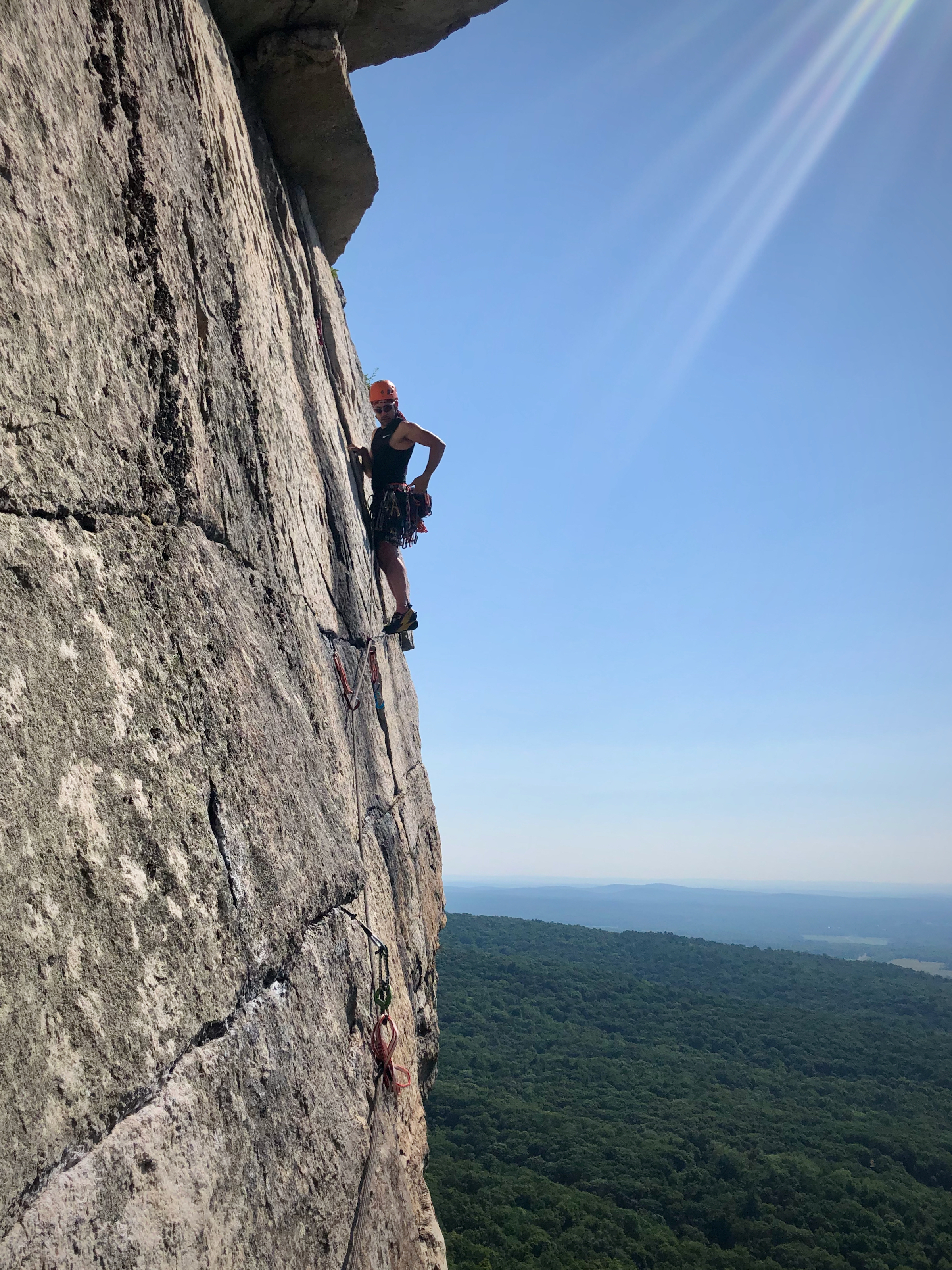

Photo: Rita Strauss

The climbing style here in the Gunks, in upstate New York, is called traditional climbing, or “trad”: When I climb up a cliff I’m attached by a rope to a belayer standing at the bottom. For protection, I gently slot pieces of metal (nuts or cams) into cracks in the rock, and attach the rope there. If I’ve climbed 5 feet since my last piece of protection, for example, and I fall, then I’ll fall at least 10 feet before the belayer’s weight catches me. Probably much farther, due to the rope’s stretch and the slack the belayer allows me. If the fall is clean I’ll be fine, but there’s often the danger of hitting a ledge, or the ground, especially if any pieces of protection pull out of the rock. So far I’ve climbed conservatively. I hardly ever fall, and I’ve never been hurt.

Trad climbing needs some strength, a lot of skill, and a ton of courage, so courage is the main attribute I’ve cultivated. It’s disarming to be part of a community that talks constantly about fear. I often meet strangers to climb, and we trust our lives to each other. We’re afraid together, so we’re also brave together.

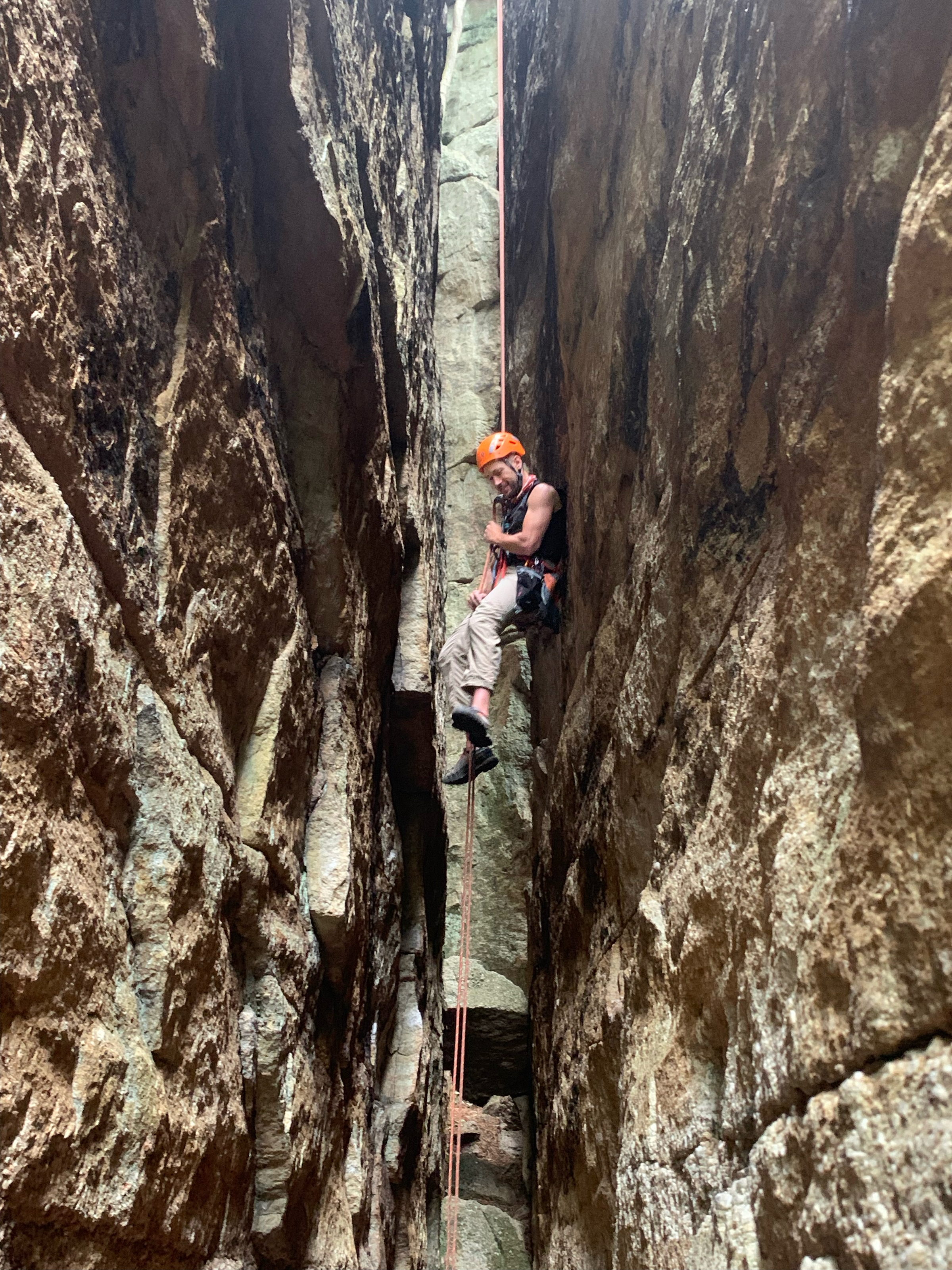

Photo: Rita Strauss

Climbing’s worth the risks for two reasons. First, because climbing is the most fun I’ve had since I was a kid. Second, because being scared on the rock is a powerful way to learn about my mind. When I’m at risk, like if I’m about to do a tricky move far above my last piece, my mind can be unhelpful. It might try to ignore the danger, telling me, “You’ll be fine, you’ve got this, don’t worry about the consequences of a fall.” Or it might obsess about the danger, distracting me from performing the move with grace.

I found it useful to read books by a climber named Arno Ilgner, and take classes from climbing coaches he’s taught, Dustin Portzline and Lor Sabourin. Ilgner advises climbers to distinguish between two modes: deciding and executing. When you’re deciding, you consider the risks and find the best way upward. Then you choose what to do and do it, with full commitment and no further thought, until you reach the next stopping point. There’s no room for criticizing yourself or wishing you were elsewhere. Ilgner says that before you have even left the ground, you must accept the consequences of your decision to climb. With this mindset, on good days, I can climb beautifully even when I’m scared.

I started the year leading very easy climbs rated 5.5, and finished by leading Roseland, a moderately-difficult 5.9, which was quite a bit more progress than I expected!

Photo: Olivia Bernard

Photo: Jordan Shapiro

It wasn’t all mind games in the Gunks, though. I spent a couple very enjoyable weeks climbing in Utah, including an intense 3-day crack-climbing clinic in Indian Creek with Mary Eden, aka TradPrincess.

Photo: Alex Lemieux

Photo: Spencer McKay

This fall I spent a few days in Rumney, the Northeast’s premier sport-climbing area. It was cold and wet, but I was camping with friends so I mostly had fun.

Wrecking My Life #

Climbing makes a lot of people quit their jobs, run away, and become van-dwelling dirtbags. I didn’t go that far, but I did buy a house in New Paltz, then quit my job for 8 months to climb. While I was on break, I saw no reason to return to our apartment in NYC, which annoyed Jennifer. She asked, “Where do we live now?” She decided to move her necessities and the hamster to New Paltz for the summer. A month later, we discovered that we had decided to leave our apartment permanently, although we didn’t remember the moment when we decided. Moving the hamster upstate had somehow resulted in moving ourselves upstate for good. In August we packed up, and I filmed one last sunset over the East River from our window before we left.

I lived in NYC for 18 years, and I swore I’d never leave. It’s hard to make and keep friends in middle age and I didn’t want to start over. But enough of my friends had drifted or moved away, especially during the pandemic, that I had no choice about starting over. In fact, so many friends have moved to the Hudson Valley, coming to New Paltz has kept me closer to my old friends than if I’d stayed in the city.

The other reason to stay in NYC had been my Zen Buddhist community, the Village Zendo, where I’ve practiced since 2004. The zendo was closed for the pandemic and stayed closed for frustratingly long. By the time they reopened this spring, I’d decathected. I’m accustomed now to meditating in the mornings with Jennifer at home, going to the New Paltz Zen Center once or twice a week, and seeing all my NYC Zen friends on occasion. That said, it was a homecoming I’d ached for when we finally did a 10-day retreat together this summer, and an in-person shuso hossen in the city this fall.

Being Useful #

I promised to be not completely useless to other people while I was off work. I restarted the Village Zendo’s meditation program at Sing Sing prison after a two-year Covid closure, enduring more bureaucratic exasperation than I could possibly have anticipated. Most of our old volunteers are once again permitted to enter. A handful of the prisoners we used to sit with have rejoined us; it’ll take time to rebuild.

Sanghas Supporting Refugees, a project of the Village Zendo and some other Buddhist groups, along with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, raised a bunch of money and resettled Javier, a trans man fleeing persecution in Colombia. We found him an apartment, an internship, health insurance, English classes, and much more. I helped primarily with the fundraising. I met Javier in October.

Computers #

I thought I’d have time, on rainy days or when I was too tired to climb, to read more computer science research and learn some of the areas I’ve ignored, like machine learning or DevOps. But in fact I climbed most days, and moving from NYC cost many of the rest. I read a few papers, and started learning queueing theory, and I had a good time speaking at PyCon and attending HPTS.

Ready or not, I returned to work two weeks ago on December 1 as planned. I’m still at MongoDB, where I’ve worked since 2011, but I have a new job: I’m a researcher at MongoDB Research. I don’t yet know what my initial focus will be. In general, I’ll try to stay current with research in industry and academia, especially in distributed databases, and look for techniques that could make MongoDB better. When I find something promising, I’ll make a prototype or do some experiments, write a report, hand off the winning ideas to engineering teams, and repeat the cycle. I haven’t done much research before. I only have a BA and I was never more than competent at math, but I’ve been around the block a few times and might have developed some intuition about what’s useful. Wish me luck!

During my sabbatical I’ve fallen in love with the Gunks and being outside, not just climbing. Now that it’s too cold to climb here I still go on a hike once a week. I’m grateful, at the age of 44, to rediscover nature. We had a relationship when I lived in a monastery two decades ago, but we drifted apart. Now we’ve found each other and won’t be separated again.