Review: Detock: High Performance Multi-region Transactions at Scale

Detock: High Performance Multi-region Transactions at Scale, SIGMOD 2023. This paper is about strict serializable transactions in a geo-distributed database. It’s named “Detock” for deterministic deadlock avoidance. My presentation to the Distributed Systems Reading Group is above, and my written summary is below.

Calvin

Detock’s goals:

- Strict-serializable, multi-region transactions.

- Low latency and high throughput under high contention.

- Handle contention between multi- and single-region transactions.

Detock descends from a lineage of “deterministic” databases invented by Daniel Abadi and others, starting with Calvin: Fast Distributed Transactions for Partitioned Database Systems in 2012. Calvin decides in advance how a sequence of transactions will execute, before the transactions fan out to the partitions. (It took me years to realize it was named for John Calvin, who taught that souls were predestined for heaven or hell.) Then there was SLOG: Serializable, Low-latency, Geo-replicated Transactions in 2019, which applies deterministic transactions to geo-replication. Detock has the same architecture and mostly the same code as SLOG, but it resolves deadlocks differently, as you’ll see.

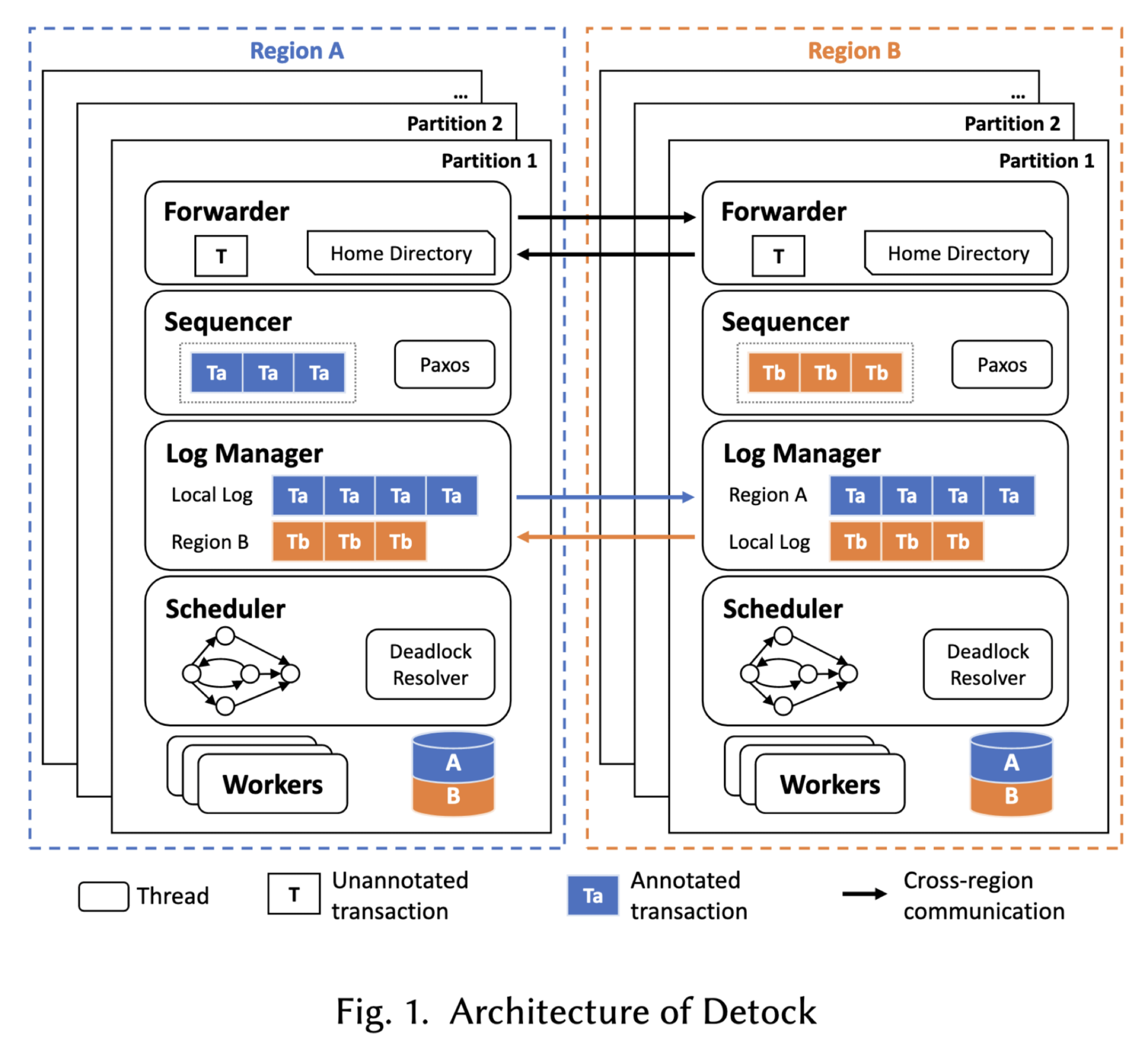

Detock’s Architecture #

Detock is partitioned and distributed across geographic regions. A region can have multiple partitions. Each item in the datastore has one home region, which holds the authoritative fresh copy of that item. An item can be asynchronously replicated from its home region to other regions; the other regions can have a read-only cache of the item.

A transaction can arrive at any partition; the partition becomes the transaction’s coordinator. Transactions are one-shot, which is a requirement of deterministic databases. We can’t do SQL-style conversational transactions. The read set and write set are either declared by the client, or can be determined with static analysis of the transaction’s code if it’s a procedure, or else the coordinator does a reconnaissance transaction to determine the read and write set. If the coordinator uses a reconnaissance transaction, and then the data changes such that the read and write set become invalid, that’s detected somehow and the transaction is retried.

The coordinator uses a “home directory” to map data items to their home regions, annotates the read/write sets with their respective regions, and forwards the transaction to all participant regions.

Single-Home Transactions #

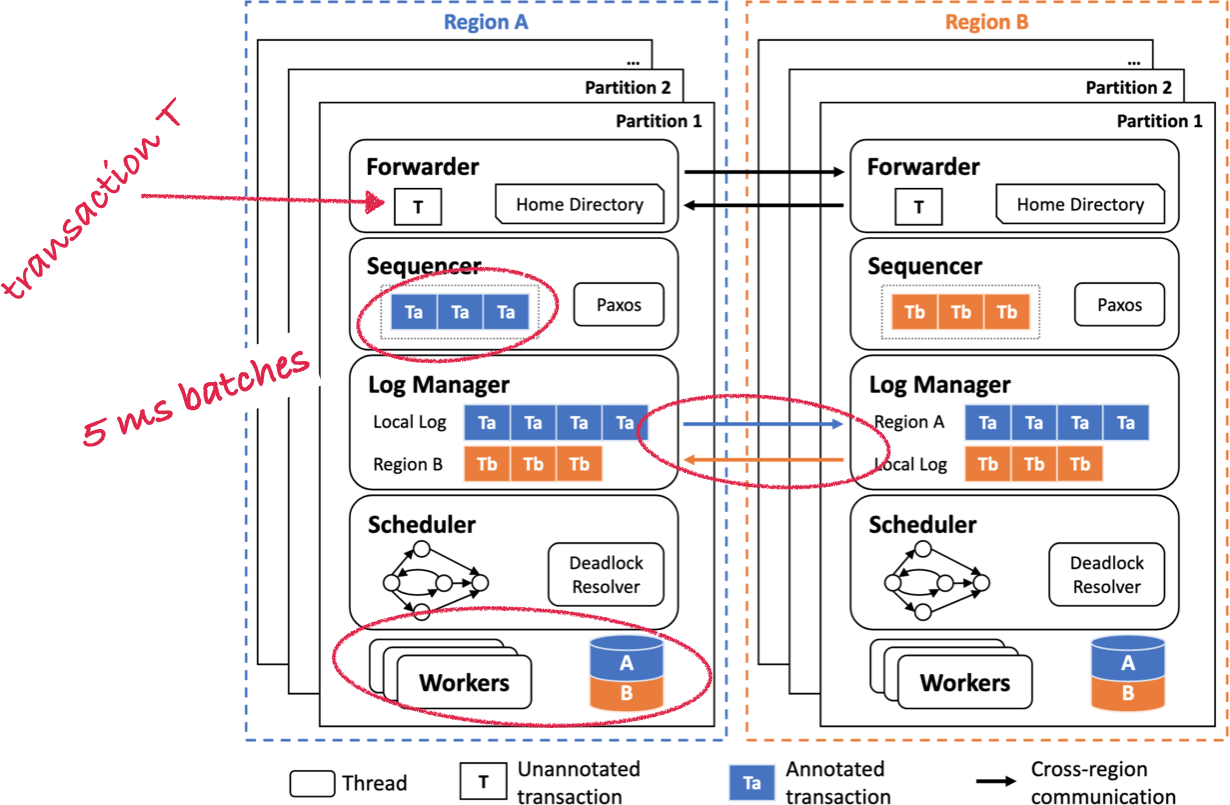

For a single-home transaction, the transaction is added to the log in its home region. These logs are stored in batches and written to disk every five milliseconds (batched to minimize disk I/O, I think).

Single-home transactions are arranged in a graph according to their dependencies, and there won’t be any cycles. The paper explains why single-home transactions can’t have dependency cycles with each other, I think this is because they’re one-shot transactions which have already been totally ordered by the sequencer. Since they can’t have cycles, they don’t have deadlocks, so the scheduler dispatches them to the workers in a straightforward way. Whenever all a transaction’s dependencies have finished, the transaction can run.

There can be single-home transactions that are in one region but multiple partitions, the Detock paper isn’t interested in these. It just says, “Transactions accessing multiple partitions in the same replica follow a deterministic execution protocol similar to Calvin and thus do not require two-phase commit.” I guess I need to re-read the Calvin paper.

Each region’s local log is asynchronously replicated to other regions. All regions replicate each other’s transactions at different times, there’s no coordination. When a region replicates a remote log it can play the transactions there to update its local copy of the remote data. I think this makes all the copies eventually consistent, but there’s no stronger guarantee.

So let’s talk about multi-home transactions, this is the interesting part.

Multi-Home Transactions #

Let’s say a transaction comes to some region, and its list of items spans several regions.

Here’s my understanding of the algorithm. A client sends a transaction to an arbitrary region. The forwarder checks the read and write sets and annotates the keys with their home regions. Since this transaction involves keys in Region A and Region B the forwarder forwards it to Region B.

In both regions, the forwarder notices that this is a multi-home transaction, so it creates something called a “Graph Placement Transaction”, I’ve drawn these as T1a and T1b.

A “Graph Placement Transaction” is the part of the transaction that only uses keys in one region. So T1a is the part of the transaction on keys in A, same for T1b. Graph Placement Transactions are like single-home transactions, and they’re added to a batch by the sequencer, like single-home transactions. But scheduling them is much more complex than scheduling single-home transactions.

Let’s say another transaction T2 arrives around the same time in Region B. And let’s say that T2’s Graph Placement Transactions are sequenced so that T2 is first in Region B and second in Region A.

The two regions’ log managers communicate the sequences they chose. As these Graph Placement Transactions arrive they’re processed by the scheduler. They arrive in different orders at different regions’ schedulers. So maybe in Region A, T1 arrives before T2, and vice versa in Region B. So the scheduler can’t just execute each transaction as soon as possible once all conflicting transactions are finished, that would lead to different outcomes in different regions. We need some way for these Graph Placement Transactions to be scheduled in the same order everywhere, despite the asynchronous replication. The authors write,

GraphPlacementTxns establish an order between multi-home and single-home transactions at the region that generated the GraphPlacementTxn. However, they do not globally order multi-home transactions, since two different regions may generate GraphPlacementTxns for a set of multi-home transactions in different orders. There is thus a concern that the generated graph may contain cycles, which would lead to deadlock during processing.

This deterministic scheduling is where Detock diverges substantially from SLOG. It’s the major contribution, and the hardest for me to understand.

Deterministic Deadlock Avoidance #

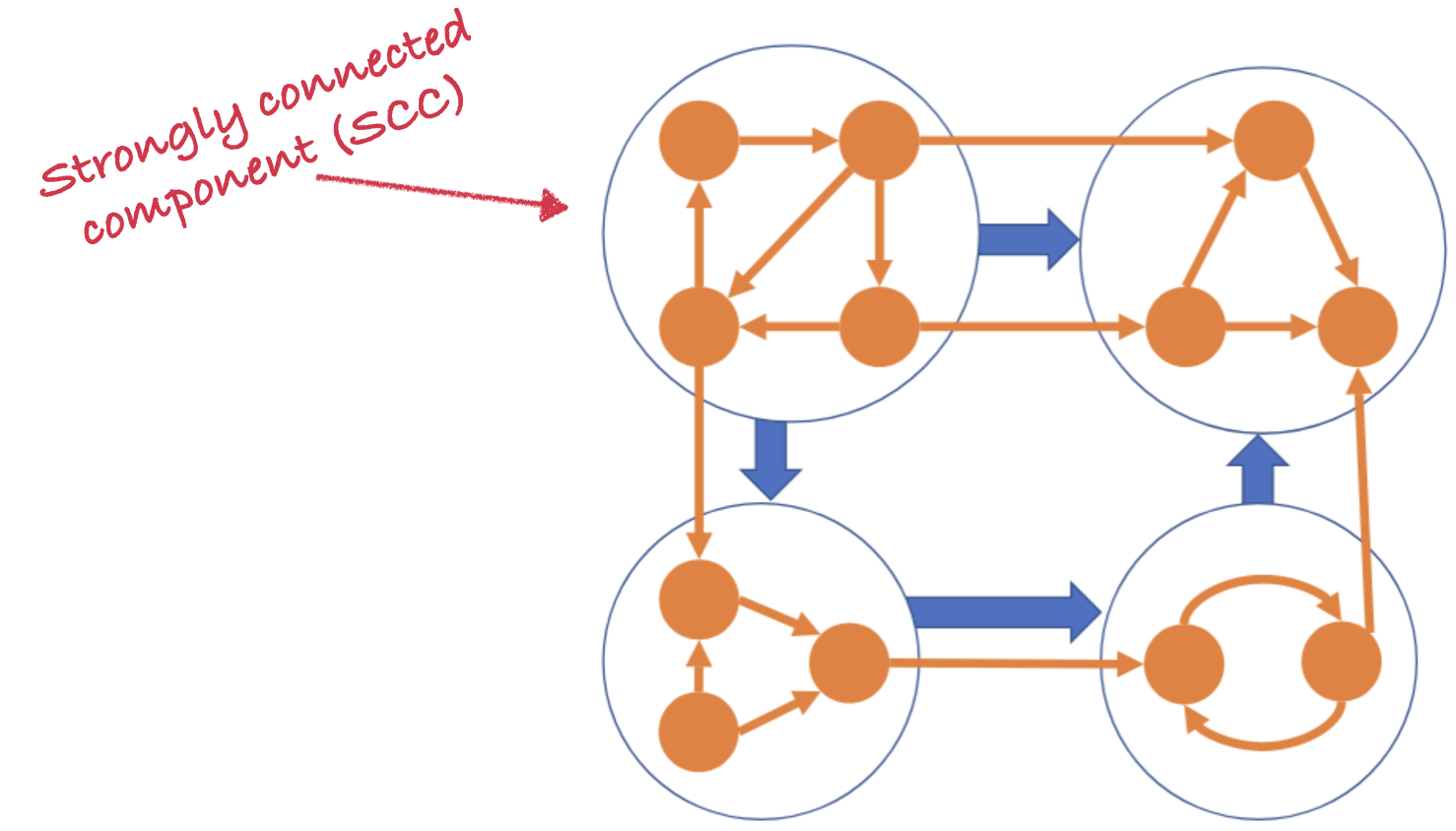

To explain Detock’s deadlock avoidance, first imagine you know all the transactions that will ever occur, and you know the dependencies among them. You can condense the dependency graph into strongly connected components (SCC).

A strongly connected component (SCC) is a subgraph where all the transactions are reachable from all the others. Therefore it contains at least one cycle. Within an SCC, Detock schedules transactions according to their unique transaction ids, which are assigned by their coordinators. Among SCCs there are no cycles: the blue arrows can’t form cycles, since you’ve isolated the cycles within the orange SCCs. Therefore you can just schedule the SCCs by topologically sorting them.

This works if you know all transactions, but in reality transactions are arriving continuously. When is a transaction ready to be scheduled?

For every vertex corresponding a multi-home transaction T in the dependency graph, let GPTotal (T ) be the total number of GraphPlacementTxns generated for T, a counter GP (T ) is associated with T to keep track of the number of GraphPlacementTxns of T that have been added to the graph so far. We define two types of vertices:

A complete vertex T is either a single-home transaction or a multi-home transaction with GP (T ) equal to GPTotal (T ).

A stable vertex T is a complete vertex and there does not exist a path going from an incomplete vertex to T .

So a transaction is stable in a region if its Graph Placement Transactions have all arrived, as have those for all transactions it depends on. I guess GPTotal (T ) is calculated at the beginning, when the forwarder creates the Graph Placement Transactions. Once the transaction is stable it can be scheduled; transactions are scheduled in the same order in all regions.

I think that the ordering algorithm is the same as Egalitarian Paxos (“EPaxos”), and Detock introduces the mechanism for waiting until a transaction is “stable”, but that’s just my guess.

In pathological cases, conflicting transactions continuously arrive at different regions in different orders, and the set of unstable transactions grows forever. Detock gets livelocked: each transaction’s dependencies are never resolved and Detock can never start executing it. The more often transactions arrive in regions in the same order, the lower the risk of livelock. Detock improves its chances thus: the coordinators assign each transaction a timestamp in the future; a transaction is scheduled once its timestamp has passed, by which time most lower-timestamped transactions have probably already arrived. (This is very similar to Deadline-Ordered Multicast in Nezha and several earlier papers.) The authors call this “opportunistic reordering”.

Their Evaluation #

Like a lot of papers lately, Detock has a massive evaluation section. The authors compare Detock to:

- Calvin, which globally orders all transactions and has no optimizations for geo-distributed transactions,

- SLOG, which globally orders multi-home transactions using one ordering service in one region,

- SLOG (slow), which is Calvin plus global consensus for the ordering of multi-home transactions,

- Janus, an EPaxos variant optimized for geo-distributed transactions,

- CockroachDB, which uses Spanner-style nondeterministic concurrency control based on synchronized clocks.

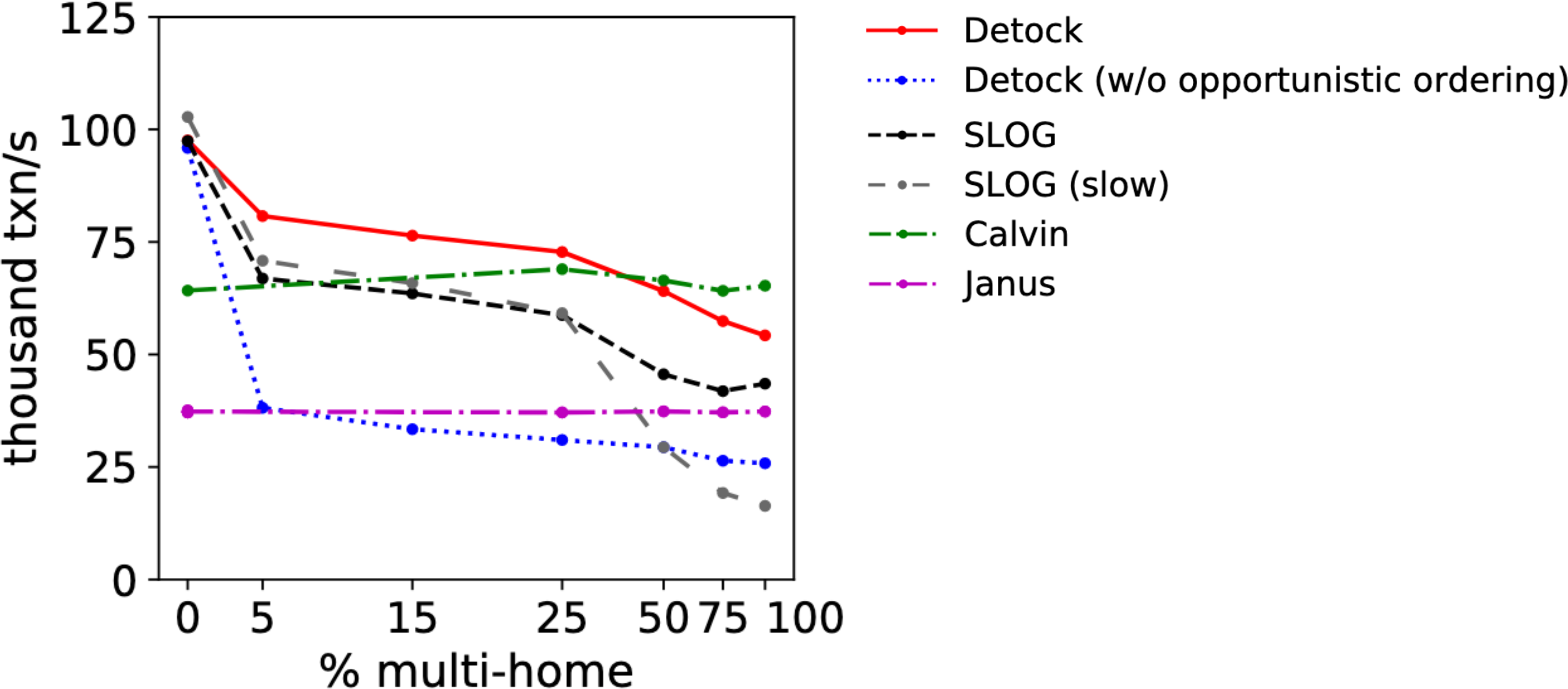

For a fair fight, they reimplemented the first four protocols within the same codebase as Detock. They vary workload skewness, network latency, the ratio of multi-home to single-home transactions, the ratio of multi-partition to single-partition transactions within a region, etc. etc. for multiple benchmarks. I was most interested in this sub-chart of Figure 6 (I’ve edited its layout):

This is a YCSB experiment with high contention (a few very hot keys) and no data partitioning within regions. It’s a rare example of a system not beating all rivals in all circumstances in its evaluation section. Detock’s throughput falls as the percent of multi-home transactions rises, since multi-home transactions require more work at more regions than single-home. When most transactions are multi-home, in fact, Calvin’s naïve algorithm actually beats Detock. The paper claims (and I agree) that this is an unlikely scenario, though.

The graph shows how critical opportunistic reordering is for Detock: the blue line at the bottom is pathetic.

In other experiments, the authors show that Detock’s distributed processing of multi-home transactions beats SLOG, where the centralized ordering service is a bottleneck. Plus, SLOG suffers more from contention, since its multi-home transactions hold locks for longer. (See the SLOG and Detock papers for details.)

My Evaluation #

This paper is well-written but its content is ineluctably complex. It’s not a single clever algorithm like timestamp as a service or leader leases. Instead, it’s a new combination of existing parts, many of them already intricate. If you don’t know Calvin and EPaxos and maybe SLOG, this paper is hard to read. But its complexity is realistic: real distributed databases are horribly complex. We make them by combining all the state-of-the-art components, trying to stake out an unclaimed position on the Pareto frontier. If you think Detock is complex, try a real-world protocol like Cassandra’s.

The authors can’t claim “our protocol is absolutely the best”; as always, they have to claim “our protocol makes better tradeoffs in realistic scenarios”. Detock looks like a solid improvement over previous similar systems, and I appreciate the giant effort the authors made to benchmark Detock and report their results honestly.