Dharma Talk at Sing Sing: Joy And Pain of Bearing Witness

These are notes for a dharma talk I gave Sunday to group of prisoners who practice Zen in Sing Sing. The day before, my temple the Village Zendo showed Sara Bennett's photos of women convicted of murder, who are rebuilding their lives after incarceration. When I went to Sing Sing, I talked about reentry, and about witnessing suffering when there's nothing we can do.

The sangha here in Sing Sing is really important to me, but it's hard for me to understand why. I'm only here a few hours a month. You can't do anything for me, and I can't do anything for you. I can give a little advice: "Sit up straight. Sit in a chair if that's more comfortable. Allow each thought to come and go; don't get attached to a thought." That's about it.

If volunteers didn't come from the Village Zendo, you couldn't use this room in the chapel. It's a silly rule, but I think it's a gift, because it gives us a reason that we have to come here week after week. And once we're here, we bear witness.

Why is bearing witness so important to me?

I think it's because we have a real connection here. I see who you are, you tell me a little about your lives. Not just your lives in prison, but where you come from, where you're going. You see me, too. We make a connection despite everything that separates us. The prison separates us, our upbringing and the trajectory of our lives separate us, but we see and know each other nevertheless. Connecting this way is a fulfillment that I can't imagine ever giving up.

It's painful, sometimes. You tell me stories that are so sad or scary, or I hear about something that happened to you that makes me so angry I can't stand it. You suffer the same way, I know: you bear witness to your families' suffering when you get letters and visits and calls from them. You hear about what's going on outside and you can't do anything about it. But don't shut them out: witnessing their struggles is worth the pain, because it's a way of being a real connected human.

The bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, is typically shown with thousands of hands. In each hand is an eye so she can see everyone in all directions, witness our suffering. Her Chinese name Guanyin means "hearing the cries." She hears the cries of suffering beings, but what's the expression on her face? She smiles.

Our branch of Zen is the Zen Peacemaker Order, and we practice three tenets: Not knowing, bearing witness, and loving action. The middle tenet is defined like this:

Bearing Witness is merging or joining with an individual, situation or environment. From this intimacy, we can choose an appropriate response to the person or situation, actions that arise from not-knowing and bearing witness.

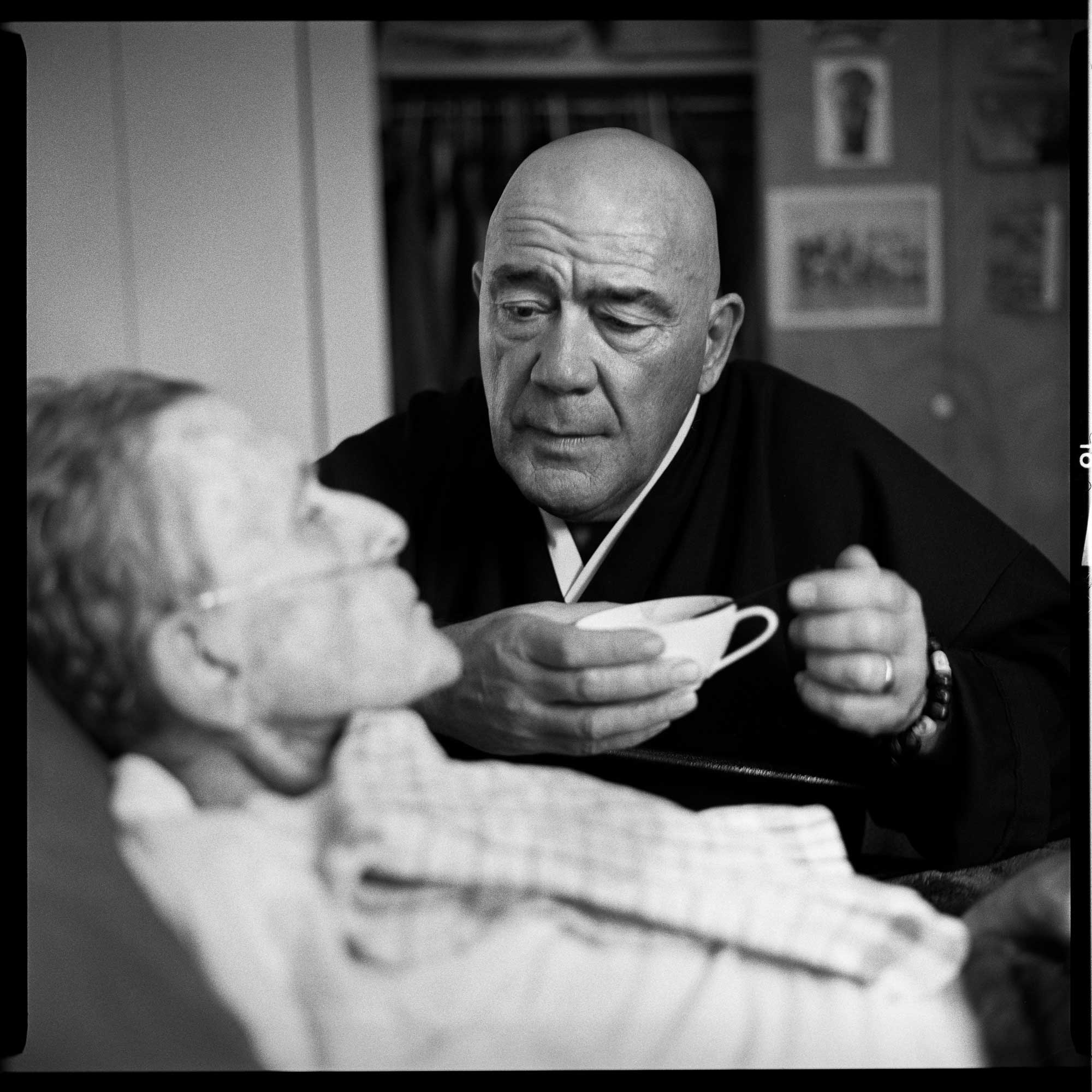

Back in 2012 I was photographing a Zen priest named Chodo, who was caring for his friend John. John was dying of lung disease, and the day I went, John was very groggy and out of it. He was bedridden and on painkillers and incredibly weak and thin. He had less than a month to live. Chodo fed him a few spoonfuls of soup, put vaseline on John's lips. He'd known John for more than twenty years. They loved each other so much and they knew there wasn't much time left.

I couldn't stay for more than a few hours taking pictures, it was too intense. I left the apartment sad and shaken, but also joyful, because I'd connected so strongly with something that was really happening. I couldn't do anything for John or Chodo, besides bearing witness. But that was enough.

(The New York Times's Joshua Bright spent a year photographing Chodo and John. "My consciousness became richer for it. As I would leave John’s bedside to return to my wife and son, I was positively euphoric.")

It was a December afternoon, and there was an event going on in the neighborhood called Santacon. It's awful. Santacon is supposed to mean "Santa convention," but it's just a bar crawl. Thousands of white people in their 20s come to New York one Saturday every December dressed up like Santa Claus, and they go from bar to bar starting at 11 am and get completely wasted and act like idiots. They get in fights and puke on the sidewalk and make the city horrible for everyone.

That particular Saturday I came out from John's apartment, it was sunny and 40 degrees, and right there on West 46th St were a dozen drunk Santas and Mrs. Santas stumbling along. A Santa with his red jacket open and no shirt under, with his pants kind of falling off him, was too drunk to feel the cold. He stood over an old black man in a wheelchair who was on the corner begging for change. Santa shouted at the man in the wheelchair, "You should be fucking grateful, man! I just gave you a fucking five dollar bill, man, you're fucking lucky cuz I didn't have anything smaller! It's your fucking lucky day!"

What a contrast between drunk Santa and me. It's not just that I'm a good person and he's bad—that was true, in that moment. He was causing suffering and I was practicing mindfulness. But also, I was happy and whole, and he was in hell. Santacon is hell. Yelling at a beggar in a wheelchair because you're drunk and privileged and you can't connect with him, you're not getting the thanks you deserve for giving him a whole five dollar bill, it's the opposite of bearing witness. It's hell.

But there's a bit of Drunk Santa in all of us, right? Whenever we try to help someone and it doesn't work out like we expect, we risk getting frustrated. Take a deep breath and remember who you are.

At the Village Zendo last night we had a photography exhibit and a discussion. The show was called Life After Life in Prison, by the photographer Sara Bennett. She knows four women who had life sentences and were released on parole after 15, 25, in one case 35 years in prison. Their names are Tracy, Keila, Carol, and Evelyn. Sara followed these women for the last few years as they've reentered society, and she photographed them with their families and at work, to tell their stories. She shows convincingly the joy and sorrow of trying to pick up your life after a devastating loss of years. Sara and the four women she photographed were all at the Zendo last night talking to us about the project and their lives.

Carol, one year after her release. © Sara Bennett

I told them I was coming to Sing Sing today, and asked what they wanted to tell you:

Tracy:

Reentry starts inside. As soon as you know your date, even before you know your date, you're reentering society. It's all within you. You gotta do it for you.

A lot of reentry info that you can get inside is outdated. You have to network, stay in touch with people on the inside and outside who can help you with information, like organizations that can help you find a job and housing.

Sara:

The two great hurdles are housing and employment. There are organizations that can help.

Carol (who was paroled after 35 years):

Be honest with yourself. Pace yourself, don't play catch up. You'll feel pressure to make up for lost time, but you cannot. Be with people who know what you're going through, try to find a place where you're taken care of, where you can take it slow.

Keila says the same thing:

The time you lost is water under the bridge, you have to say goodbye to those years. When you get out, you start fresh.

I hope that helps at all.

Back on the topic of bearing witness: the photographer, Sara Bennett, she bears witness when she photographs these women struggling to find their way. She shows us her photos and introduces us to the women so we can hear them directly. It's not purely witnessing, either: Sara showed her photos in Albany, in the legislative office building, where the governor and legislature might see them. She's an activist fighting for clemency, to make parole boards more merciful, and to ensure that people getting out of prison have more support. So bearing witness translates into action, for her. There is something that we on the outside can do, and must do, for people released from prison.

But bearing witness starts it. Sometimes it's all you can do, and it has to be enough.