The Green Matrix

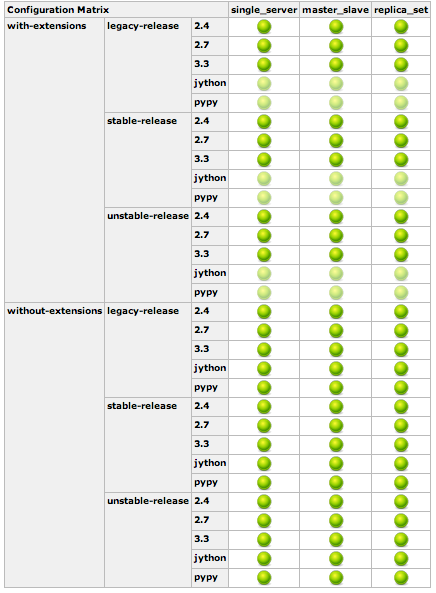

For a year and a half I've been part of the team maintaining PyMongo, the Python MongoDB driver. It's one of the most widely used Python packages with 1.5 million lifetime downloads. The code itself is only moderately complex; about 8300 source lines. What makes it a tiny horror to work on is the range of environments we support. Here's our test matrix in Jenkins:

That's 72 test configurations. (It looks like more than that, but we don't test Jython and PyPy with C extensions compiled since that currently doesn't make sense.) The dimensions are:

-

Python version: We support CPython 2.4 through 3.3. On each commit we test just the highlight versions: 2.4, 2.7, and 3.3. We also support the latest Jython and PyPy. We test the intermediate versions like 2.5 and 2.6 before a release.

-

C extensions: we have a few key parts of PyMongo implemented in C for speed, with pure-Python versions as a fallback. We test both modes.

-

MongoDB Version: We test the latest development branch of MongoDB (2.5) plus the last two production versions.

-

MongoDB Configuration: We set up a single server, a master-slave pair, and a three-node replica set, and run mostly the same tests against all.

In each test configuration, PyMongo's test suite has about 430 individual test functions.

This covers the main test matrix, but there are some auxiliary tests we run in Jenkins on every commit. We have a mod_wsgi test that runs a few thousand web requests (first serial, then parallel) against a web app using mod_wsgi in a range of configurations:

-

Python 2.4, 2.5, 2.6, and 2.7

-

mod_wsgi 2.8, 3.2, and 3.3

-

The latest production MongoDB as a single server or replica set

The mod_wsgi tests are there to ensure we never recreate a connection leak like the apocalyptic "unbounded connection growth with Apache mod_wsgi 2.x" bug to which I lost some of the best weeks of my life.

I've also set up some tests for Motor, my non-blocking MongoDB driver for Tornado: I run in Python 2.6, 2.7, and 3.3 against a single MongoDB server and a replica set, running the three most recent versions of MongoDB. I have a separate Motor test that connects to MongoDB over SSL, and finally I have a test of "Synchro," which wraps Motor inside a resynchronization layer and checks it can pass all the same tests as PyMongo. In all, Jenkins runs 33 test configurations for each Motor commit.

Jenkins automatically tests our main configurations, but we periodically hand-test some additional configurations, like sharded clusters, beta releases of Jython and PyPy, and Windows. We'll put some of these in Jenkins too.

For a team of three people to build and maintain this volume of test infrastructure is a huge effort. It's clearly worth it, because the test matrix is so large. But it's not much fun.

Lessons learned:

-

Test code is a liability: Too much testing code is as bad as too much of any other kind of code. Write as few tests as possible to cover the cases you need to test. Over-testing comforts the novice but impedes agility. For example, when we renamed PyMongo's Connection class to MongoClient, I had to change over 1000 lines in 32 files in the test suite. A commit that huge is a barrier in the repository's history, across which no commit can be moved without conflicts. I hope to never do anything like it again. The test suite should be smaller and better factored.

-

Tests must be very reliable: It needs to be not only minimal but also very reliable. Tests should fail if and only if the behavior they test breaks. When I joined the team, PyMongo's tests often failed "just cuz." Fixing them all took months: We'd observe an intermittent failure in Jenkins due to some race condition that we couldn't reproduce on our laptops (an EC2 "medium" instance runs a three-node MongoDB cluster slower than you could possibly imagine). We'd think real hard and finally understand and fix the failure. Then we'd do the same for some other test. It was a costly exercise but necessary: It's not until our tests always passed that we took them seriously when they didn't.

There are other dicta that I find negotiable: tests should be fast, sure, but I can live with a test suite that takes a few minutes to run per configuration. Perhaps test methods should include only one assert, but I can live with several asserts in some methods.

I'm implacably opposed to mocking when it comes to testing PyMongo: what our tests verify is primarily our understanding of how to talk to MongoDB. If we mocked any aspect whatsoever of the MongoDB server, our tests would be worse than useless. Virtually every test of PyMongo is an integration test, so we make no distinction between "unit tests" and "integration tests."

I'm curious what others have learned from maintaining a driver's test suite. It seems to be a lot of hard work no matter what.