These Unreliable United States

Audio only:

(Podcast subscription: https://emptysquare.libsyn.com/rss)

Transcript

Where were you when they called it yesterday?

I was biking through Brooklyn and I looked down at my phone to check directions, and I saw the text from Keishin saying, “It’s done.”

And over the next few minutes, the streets erupted around me. People were honking their horns and yelling and waving their fists. Every block that I biked after that, I had to go slower because the streets were getting crowded. People were just pouring out into the streets.

On Vanderbilt Avenue, it kind of turned into a dance party. Every car that crossed through an intersection was honking, and the people in the street would like wave and yell back. By the time I got to Grand Army Plaza at Prospect Park, traffic was stopped and there were boomboxes and loudspeakers out, and it was like a rave. It was like the end of a war.

In 44 BC, after Julius Caesar was assassinated by Brutus and the gang to save the Roman Senate system, the old statesman Cicero wrote, “The tyrant is dead, tyranny lives.”

Cicero was pointing out that killing Caesar didn’t fix the problem. The hole in the Roman Republic’s defenses that Caesar had walked through—it was still there and the Senate didn’t patch it.

The factors that made Roman democracy vulnerable to tyranny were still there. The plebeians were disenfranchised and poor and vulnerable to bankruptcy and war. And the republic didn’t serve them; it made them ready to follow any populist autocrat who came along.

After Caesar, the hole in the republic’s defenses was still there to let in anybody who wanted to walk through it. Maybe somebody more dangerous than Caesar: his son, Octavian. In the power struggles after Caesar’s death, Octavian came out on top. He became emperor in 27 BC, and that is dated as the end of the Roman Republic forever.

So you understand what I mean: We defeated Trump, but this isn’t a victory. This is just a temporary stalemate. The holes in our democratic system are still there, and I don’t think that we have the opportunity to patch them right now.

The Republicans are still probably in control of the Senate, definitely of the Supreme Court, state legislatures, and their strategy is anti-democratic. They have no interest in making our system more representative. Which means that somebody more dangerous than Trump—some intelligent, disciplined, ambitious, farsighted, young Octavian can walk through that hole any time. And I think that when that happens, things are going to be dicey.

Back in 2016, right after Trump won, a friend of mine said something really insightful to me. He said that the reason why people were so shocked is that for the first time, they saw the death of the Republic.

Not right away, not in 2016 and apparently not in 2020, but we saw that it was possible for our system to end. And so we realized that it was probably inevitable.

People alive today, we didn’t live through the Civil War, or the election of 1876, or any other constitutional crisis of that size. So we’d come to expect a certain continuity. And the election of Trump woke us up to the impermanence of the United States as we know it.

I read something similar in an interview with Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut, talking to the Times a couple of months ago. Chris Murphy said,

I have a real belief that democracy is unnatural. We don’t run anything important in our lives by democratic vote other than our government. Democracy is so unnatural that it’s illogical to think it would be permanent. It will fall apart at some point, and maybe that isn’t now, but maybe it is. So I feel like my job is to hold this together so that it survives to the next administration.

I think that’s extraordinary, for a sitting senator, Chris Murphy, to admit that truth, that government by the people, for the people, shall perish from the earth someday.

But we already know this, because Buddha taught impermanence. He taught that nothing lasts. We can’t rely on anything at all.

Buddha’s greatest teaching of impermanence was when he himself died. He was 80 years old. He ate his final meal, and he sensed that he would die soon, so he laid down between two trees, laid on his side, and gathered the sangha around him. He said, “Everything decays. Strive in your practice with diligence.”

He told his beloved attendant Ananda this:

O Ananda, be lamps unto yourselves. Rely on yourselves, and do not rely on external help. Hold fast to the truth as a lamp. Seek salvation alone in the truth. Look not for assistance to any one besides yourselves.

And how, Ananda, can a sister be a lamp unto herself, rely on herself only and not on any external help, holding fast to the truth as her lamp and seeking salvation in the truth alone, looking not for assistance to any one besides herself?"

This is from an old translation by Paul Carus, so I’ve fixed the sexist pronouns. Buddha says that a brother or sister practices like this: She lives in her body, but because of her diligent, thoughtful, mindful practice, she overcomes the grief that arises from the body’s cravings. She has sensations, but through practice, she overcomes the grief that arises from craving due to her sensations. She thinks and reasons and feels, but due to her diligent practice, she overcomes the grief that arises from thinking and reasoning and feeling.

Buddha said,

Those who, either now or after I am dead, are lamps unto themselves, relying upon themselves only and not relying upon any external help, but holding fast to the truth as their lamp, seeking their salvation in the truth alone, and not looking for assistance to any one besides themselves, it is they, Ananda, who shall reach the very topmost height! But they must be anxious to learn.

I think that this message is very simple and very clear, that we can’t rely on anything or anyone besides our own insight and our own practice.

This country that we’re struggling to save, it’s a noble struggle and we must keep it up. But we can’t rely on the outcome of this struggle for our sense of peace, for a sense that our lives have meaning. The meaning of our lives is independent of anything as superficial as the life or death of our country.

No thing is going to free us from grief. The important work is that we practice waking up.

Once upon a time, there was a statesman who had a lot of questions about how to govern his country, and he thought that Buddhism might have the answers for him. His name was Emperor Wu of Liang. And there’s a koan about him that goes like this (adapted from Thomas Cleary’s translation):

Emperor Wu commanded the great master Fu to explain the Diamond Sutra.

The great master Fu shook the lectern once, then got down from the seat.

[Shakes his laptop forcefully, causing the video to shake.]

The emperor was flabbergasted.

Master Shi asked, “Does Your Majesty understand?”

The emperor said, “No.”

Master Shi said, “The great master Fu has explained the sutra.”

Poor Emperor Wu. He’s the fall guy in a couple of stories that go this way, because he’s got a habit of doing this kind of thing. There’s another story about him where he commands the Zen master Bodhidharma to explain things to him, and he’s disappointed in that story, too.

So, in this koan, Emperor Wu asks master Fu to come and explain the Diamond Sutra. The Diamond Sutra is about emptiness and impermanence. And it’s also about the Bodhisattva path—what we should do and how we should practice from day to day to wake up, and to help each other wake up.

Emperor Wu heard that there’s a monk named Fu, who can explain these things to him. Emperor Wu sends soldiers to get master Fu, and they find him in a market selling fish. He’s a thin little old man, sitting on the ground in the dirt by the side of the road, with a pile of smelly fish in the sun in front of him. He’s just trying to make a living.

A group of soldiers walk up clanking, with their spears and their breastplates and they say, “The great Emperor Wu demands your presence.”

Fu shrugs and says he’s not interested. So they pick him up at the elbows and they cart him off to the capital. When he gets there, in his ragged robe, he’s marched into the palace and up to a seat on the platform in front of the emperor, surrounded by his officials and his bodyguards. And the emperor says, “Give me explanations!”

But Fu doesn’t have any. The emperor wants to buy something that Fu isn’t selling. All he has is fish.

[Shakes his laptop.] “Wake up!” That’s what master Fu has to say: “Wake up.”

Practicing Buddhism is not going to tell us how to live in a country that’s on the edge of self-destruction. It doesn’t tell us how to feel or what to do. Buddha said, “Rely on yourselves, and do not rely on external help.” And he also said to practice diligently. Free yourself of the grief of wanting things to be different.

Buddhism doesn’t have any answers for sale. All it’s offering is a way to free ourselves from grief and delusion. And when we act with freedom we choose our own way of living in this whole shitstorm.

We are on our own now more than ever before. We’re separated from each other. We can’t see our teachers face to face. We can’t practice together in the zendo or at a retreat center. We have to improvise how we do everything now on Zoom.

When I started practicing Zen, 20 years ago, it seemed that it was really rigid and harsh, and I loved that. I felt like my life was careening all over the road and I wanted to be set on rails and only go straight. I wanted to live with the discipline of a Japanese monk in a movie, or in the old stories. And Zen seem to have the answers for everything. When do you bow? How do you walk and eat and sit? But it’s only like that when you’re in a monastery on retreat, and even then life doesn’t really stop. It’s still always swerving and sliding.

Look at us now. We can’t play Japanese monks in a monastery now, anymore.

The old forms that we inherited from Asia, we’ve adapted them again and again and again to every situation. But to me now, it just feels like we are way too far from the point of origin. These rituals are like a puppet show, if we did them now. There are no more people meditating in long straight rows in the candlelight. There’s no more oryoki. There’s no more kyosaku stick. We can’t rely on these old forms anymore. We have to invent something new.

And it’s always already been this way, it’s just that we can see so much more clearly now, that the old forms don’t last. The Village Zendo doesn’t last. The United States doesn’t last. Nothing is reliable. No one can explain it to us. We are responsible for waking up and setting our own direction. We have to be lamps unto ourselves.

But when we live this way, as the Buddha said, “holding fast to the truth as our lamp and seeking salvation in the truth alone,” we rely on this only—not on the past or the future or life or death or success or failure—we can rely on this, this one-eyed truth.

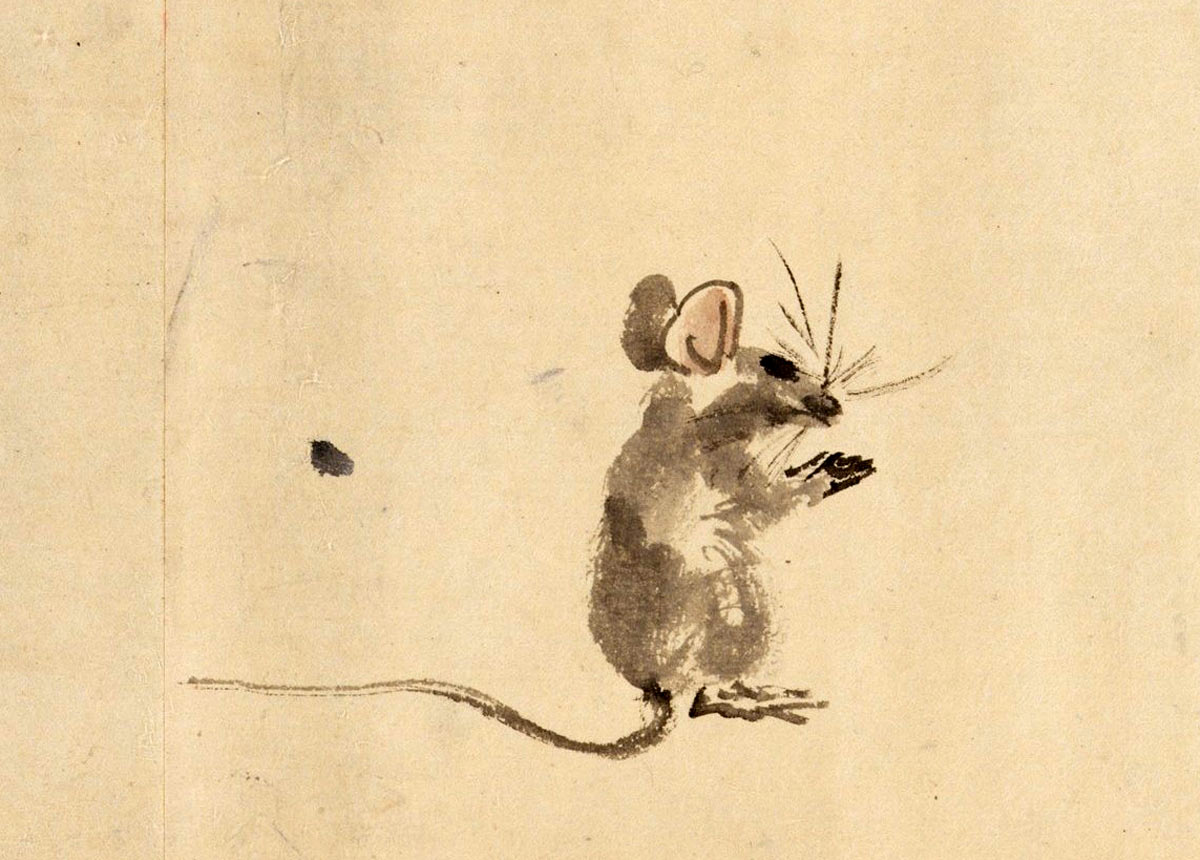

On Friday night, my partner Keishin and I, we biked down to the East River to meditate outside. And Soten joined us for our little Friday outdoor sitting group. As we were pulling into the park on our bikes, I saw, in the light from my headlamp, a tiny mouse scurrying around a tree. I shone my headlamp at it and it scurried into its hole among the roots of the tree.

So the three of us sat down. It was after sunset. I could see the lights of the cars on the FDR beyond the park, the white headlights and the red taillights going back and forth. We heard the sound of somebody calling to his dog, playing fetch.

There was a cool breeze moving through the park, moving the brown leaves on the ground, sometimes turning a leaf over. In that movement, out of the corner of my eye, I kept thinking that I saw the mouse again. And then suddenly I did see it.

And it was it was so small that it could hide under a single leaf. So it was approaching us, darting from the cover of one leaf to the next to the next, coming closer, curious about us, until it was right in front of me, almost between my knees.

It was half hidden under a leaf, and it was very still, and I could see one delicate ear, and one tiny eye, looking up at me.

Image: Detail from a handscroll painting by Kawanabe Kyosai.