How To Understand Non-Self: Buddhism And Conway's Game Of Life

On May 30, 2021, I spoke at the Village Zendo about a math puzzle called John Conway’s Game of Life, and how it helps us understand the Buddhist teaching of no-self. Here’s the video recording, with slides and animations.

Paraphrase of the dharma talk:

I’m going to describe some wonderful math. It will eventually be about Buddhism.

Let’s simulate life, with the simplest mathematical model possible.

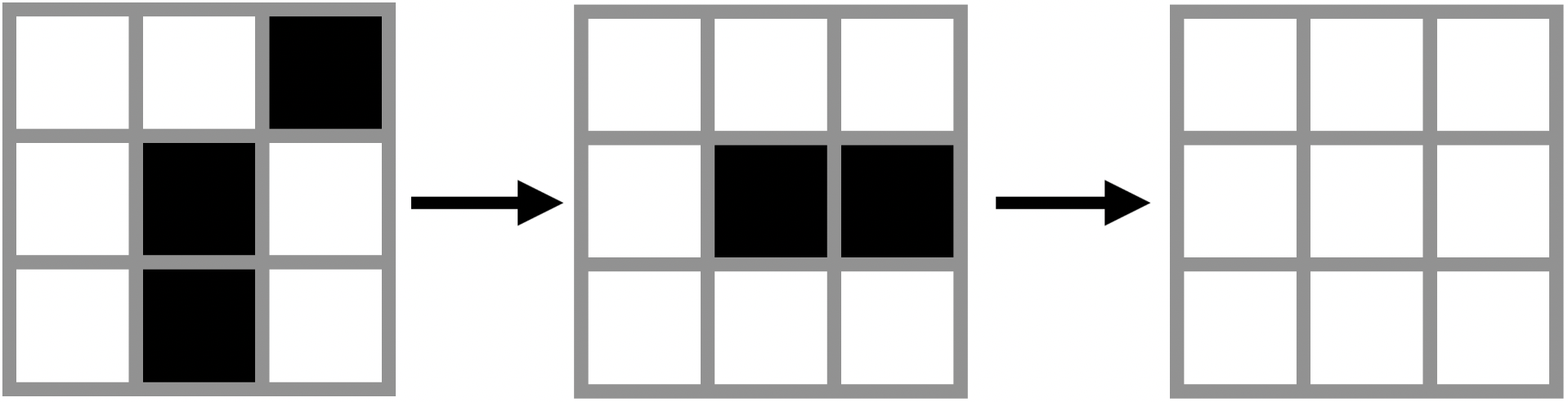

Imagine this is a colony of cells in a flat layer on a Petri dish. The black squares are living cells, the white squares are empty space.

So, how are these cells born, how long do they live, how do they die? Let’s make three simple rules.

Rule 1: Survival. #

A cell with two or three neighbors survives.

Each cell has eight possible neighbors. At each step of the simulation, mark all the cells that have two or three neighboring cells. In the next step of the simulation, those cells will still be alive.

Rule 2. Death. #

A black square with four+ neighbors dies of overcrowding. A black square with zero or one neighbor dies of isolation.

A cell with four or more living neighbors dies, as if by overcrowding. In the next step, its space is replaced by an empty white square.

A cell with zero or one neighbors dies of isolation.

Rule 3. Birth. #

An empty space with exactly three neighboring cells becomes a live cell.

The empty white square in the center will spring to life. In the next step of the simulation it will be black.

John Conway #

A mathematician named John Conway came up with these three rules around 1970. It’s not intended to be a realistic description of biology, it’s a mathematical game, which Conway called “the Game of Life”. (It’s not the heteronormative board game where you play a family trying to fill its car with children.) Conway’s idea came from decades of mathematicians exploring the question, can simple systems produce complex behavior? Could a system with a few basic rules behave unpredictably? Could it produce self-replicating organisms?

John Conway’s not a computer scientist, but he’s well-known among programmers like me for the Game of Life and similar math research that veers into computer science. I studied some of his work in college, but hadn’t thought about him much until he died last year. I read his obituary in the New York Times, and learned what a delightful person he was.

Photo: Mariana Cook, 2007.

He was born in England in 1937 and spent most of his career at the University of Cambridge, and then at Princeton. The Times said his work “ranged from the rigorously highbrow to the frivolously fun, earning him prizes and a reputation as a creative, iconoclastic and even magical genius”.

As a student, Dr. Conway cultivated his acknowledged lifelong preference for being lazy, playing games and doing no work. He could be easily distracted by what he called “nerdish delights.” He once built a water-powered computer, which he called Winnie (Water Initiated Nonchalantly Numerical Integrating Engine).

Hired at Cambridge as an assistant lecturer, Dr. Conway gained a reputation for his high jinks (not to mention his disheveled appearance). One day when he was lecturing on symmetry and the Platonic solids, he brought in a turnip as a prop, carved it one slice at a time into an icosahedron, with its 20 triangular faces, eating the scraps as he went.

Photo: Dith Pran / New York Times.

When Conway was first playing with the Game of Life, he did it by hand, trying configurations on a board for the game of Go. Soon some computer scientists made programs that can run large games fast, eventually simulating boards with billions of squares, playing thousands of steps per second. The question everyone’s researching is, given how simple the game is, what can it do?

What can Game of Life patterns do? #

Can a pattern in the Game of Life do nothing?

Block

Yes it can. This pattern is called a “block”. Each cell has 3 neighbors, so they all stay alive. No empty square has three neighbors, so there are no births. If this pattern is your initial configuration, nothing ever changes in this game. Here are some more still lifes:

Beehive

Loaf

Boat

Tub

So a pattern in the Game of Life can do nothing. Can it disappear? Yes it can.

In the first step, if we apply the three rules, then the center cell survives, the other two cells have one neighbor each so they die of isolation, and one cell is born on the right because it has three neighbors. In the next step there are two cells, both die of isolation, and in the third step the board is empty.

So yes, a pattern in the Game of Life can disappear. Can it oscillate, moving through repeating shapes? Yes it can.

Blinker (period 2)

Toad (period 2)

Beacon (period 2)

Pulsar (period 3)

Penta-decathlon (period 15)

Remember, all these animations show is steps in a simulation, where we apply the three rules at each step to produce the next shape. The only difference between these animations is the initial shape: the subsequent shapes are determined by the initial shape.

So, patterns in the Game of Life can oscillate. Can they move across the board?

Glider

Light-weight spaceship

Medium-weight spaceship

Heavy-weight spaceship

Yes, a pattern can move across the board. Can a pattern grow to infinite size? Conway originally thought not: if your initial configuration has a finite number of cells, he conjectured, the population can’t grow forever. He offered fifty dollars to the first person who could prove or disprove the conjecture before the end of 1970. A team at MIT won the prize with this “glider gun”. It shoots a new glider every 30 steps, which flies off forever. Thus from an initial configuration, the glider gun expands the size of the board infinitely in one direction, and it turns an infinite number of cells black.

Gosper glider gun

Computation in the Game of Life #

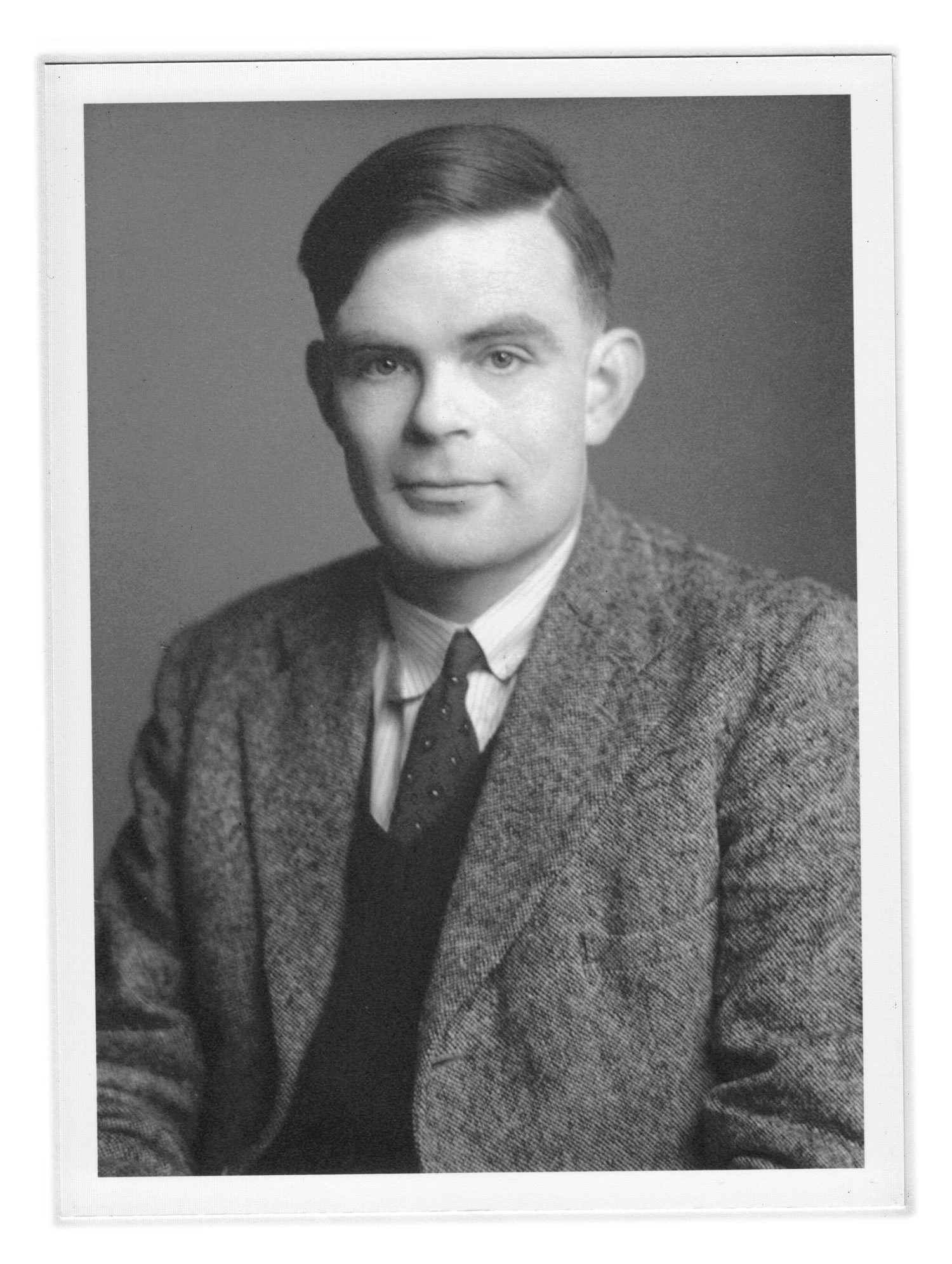

Let’s take a big jump now. Can a pattern in the Game of Life do computation? For example, could it calculate pi, play tetris, or give you a credit score? Let’s take a digression, and talk about a different English mathematician for a minute: Alan Turing.

Godrey Argent Studio

He’s famous for building computers during WWII that decrypted German submarines’ radio messages. Tragically, his work on physical computers had little influence, because it was classified until the 1970s, by which time it was obsolete. His main contribution to computer science was theoretical.

In a 1936 paper, Alan Turing described an imaginary machine. It has an infinitely long tape, which it can move forward or backward. It can read, write, or alter one symbol at a time on any position on the tape. (The tape is like its hard drive.) Additionally, the machine has a fixed number of modes (known as “states” in computer science), and it can transition from one mode to one other mode each time it reads a symbol from its tape. That’s it. The machine is so simple, you can prove theorems about it. In fact, Turing never built one, the video above shows a hobbyist’s interpretation. You should watch it in action.

Turing described his machine and claimed that anything which can be computed, could be computed by this simple machine. There’s been a century of intense research into this claim. The term “computable” is unfortunately vague, but it means something like “a series of actions, following precise rules”. For any reasonable definition you can think of, Turing’s claim is true. This is a useful fact because we can compare any system (such as real computer) to Turing’s machine to see if they are equivalently capable.

Can the Game of Life compute anything a Turing machine can? Yes it can.

This pattern is a Turing machine, constructed in the Game of Life. It’s enormous, covering millions of squares. The long diagonal line is the tape, and the rectangle in the middle is the part that transitions between modes, and moves back and forth along the tape. When the video zooms in, you can see that the machine is made of the basic patterns we saw before: still lifes, oscillators, and gliders. Every square in this machine is following the three rules of survival, death, and birth. All its power comes from how the squares are arranged at the beginning; after that, the three rules determine how the machine behaves. This is a Turing machine, and it can compute anything that can be computed. If you put the right symbols on its tape, it can play chess, it can forecast the weather, it can translate German to Chinese.

Consciousness in the Game of Life #

Here’s another big leap: can a pattern in the Game of Life experience consciousness?

So far, everything I’ve said is mathematically proven. Now we’re entering the Twilight Zone. To decide whether the Game of Life can experience consciousness, we have to answer two philosophical questions that can’t be answered with math.

Question One #

Does consciousness arise from heaps of parts, interacting according to rules?

I think that my consciousness arises from chemistry and electricity and so on, interacting mostly in my brain but also in my body and my environment. All these parts follow the laws of physics. They’re rules—not as simple as the Game of Life, but rules nevertheless. Lots of modern people with the scientific worldview believe this, maybe you do too.

The Buddha taught that consciousness arises from interacting parts. He didn’t believe consciousness arises from the brain and body, that’s a modern idea, and his theory of reincarnation doesn’t fit with it. But, he did teach that consciousness is formed from parts called “the five skandhas”, or “the five heaps”. They’re called “heaps” because they are parts that contain more parts, and each of those contains more parts and so on. Buddha taught that these parts interact according to rules, which he called karma or the law of cause and effect. His descendants wrote big analyses called abhidharma, breaking down each part of consciousness into tiny sub-sub-parts and describing the rules of their interactions.

So, Buddha and modern neurology both teach that consciousness arises from heaps of parts, interacting according to rules.

Question Two #

If I made a simulation of these parts of consciousness, interacting according to their rules, is the simulation conscious?

If you simulate a brain, or the five skandhas, is that consciousness? I think it is. Here’s my argument: Consider these heaps of parts of consciousness, each part is made of parts and so on, and you replace just one of the tiniest parts with a machine that simulates it. For example, say you replace just one of my hundreds of trillions of synapses with an electronic device. The device follows the same rules, so the whole collection of parts behaves exactly the same as before you replaced one synapse. The change isn’t detectable to me or anyone who observes me. It would be unreasonable to claim that I’ve lost consciousness.

You see where I’m going with this. If you replace the parts of my consciousness with a simulation, one by one, there’s never a moment when it’s reasonable to say I’ve lost consciousness. The final result must still be conscious, therefore a simulation of consciousness is conscious.

In summary:

- Consciousness can be simulated (since it’s governed by rules).

- A simulation of consciousness is conscious (by the replacement argument.

- Simulation is computable (anything that follows rules is).

- A Turing machine can compute anything computable.

- The Game of Life can compute anything a Turing machine can (it can contain a Turing machine).

- A pattern in the Game of Life can simulate consciousness.

- A pattern in the Game of Life can be conscious.

This hasn’t happened yet, since we don’t know the rules governing consciousness in enough detail to design a Life pattern that could simulate it. But it’s theoretically possible, and that’s important.

No-Self #

Buddha Expounding the Dharma, 8th C. Sri Lanka (Anuradhapura). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Why am I talking about the Game of Life in a dharma talk at the Village Zendo?

A foundational teaching of Buddhism is that there’s no self, even though we experience being individual people. It’s important to develop insight into this fact, to grasp it intuitively, not just study no-self as a concept. The Game of Life was helpful for me: there’s just white and black squares and three simple rules, yet you can see how, with the right starting configuration, it produces any universe you could imagine. It could produce a conscious being, who is unaware that it is made of black and white squares.

The same with the ourselves. We’re heaps of parts, interacting according to rules. That’s not how it feels. I feel like I’m one permanent thing, therefore it’s easy for me to get attached to the thing of my self, and to mourn at the thought of losing my self to sickness, old age, and death. But all that happens is the heaps of parts that produce my consciousness come together, persist for a time, and then dissolve.

John Conway died in April of 2020, of COVID. He was 82 years old. He made serious contributions to the foundations of mathematics, and he made delightful toys, like the Game of Life.

A cartoonist produced this pattern in the Game of Life to honor him:

xkcd.com

Conway was made of heaps of parts, and they dissolved. That will happen to all of us.

He treated his life a bit like a game, but a game with no goal or points. Not a game to play, but a game to play with, to see what’s possible with it, to find ways to enjoy it, to stretch it into new shapes. If we didn’t take our own lives so seriously, if we saw our temporary existence as just some heaps of parts, just some squares on a grid, maybe we could suffer less, and have more fun.