Review of "Write Great Code, Volumes 1 and 2"

There's certainly a romance to the great unfinished work, the consequence of some unreasonable ambition.

Recently in "Joe Gould’s Teeth: the long-lost story of the longest book ever written", Jill Lepore investigates rumors that a crazy Bowery drunkard wrote the annals of the whole world, everything he heard, in real-time, continuously, for years. "Writers loved to write about him, the writer who could not stop writing."

Joe Gould is best known from Joseph Mitchell's profiles of him in the New Yorker. Gould claimed, in the 1910s through the 1940s, to be composing "The Oral History", or "Meo Tempore".

"I have created a vital new literary form," wrote Gould.

"It may well be the lengthiest unpublished work in existence," wrote Mitchell.

But Gould was alcoholic, and crazy. He lost his notebooks—hundreds of them, thousands?—and those few that he did not lose, other people lost or discarded after his death in 1957. He spent his last years in the huge mental institution, Pilgrim State Hospital, where he likely was given electroshock therapy, and lobotomized.

The total loss of the Oral History is a sorry story. A mentally ill man was tragically mistreated. But retold as a fable it is romantic. "I thought of Joe as a kind of hero," wrote Mitchell. A half-century later, Jill Lepore was not so inspired by him, but still: "Joe Gould is contagious."

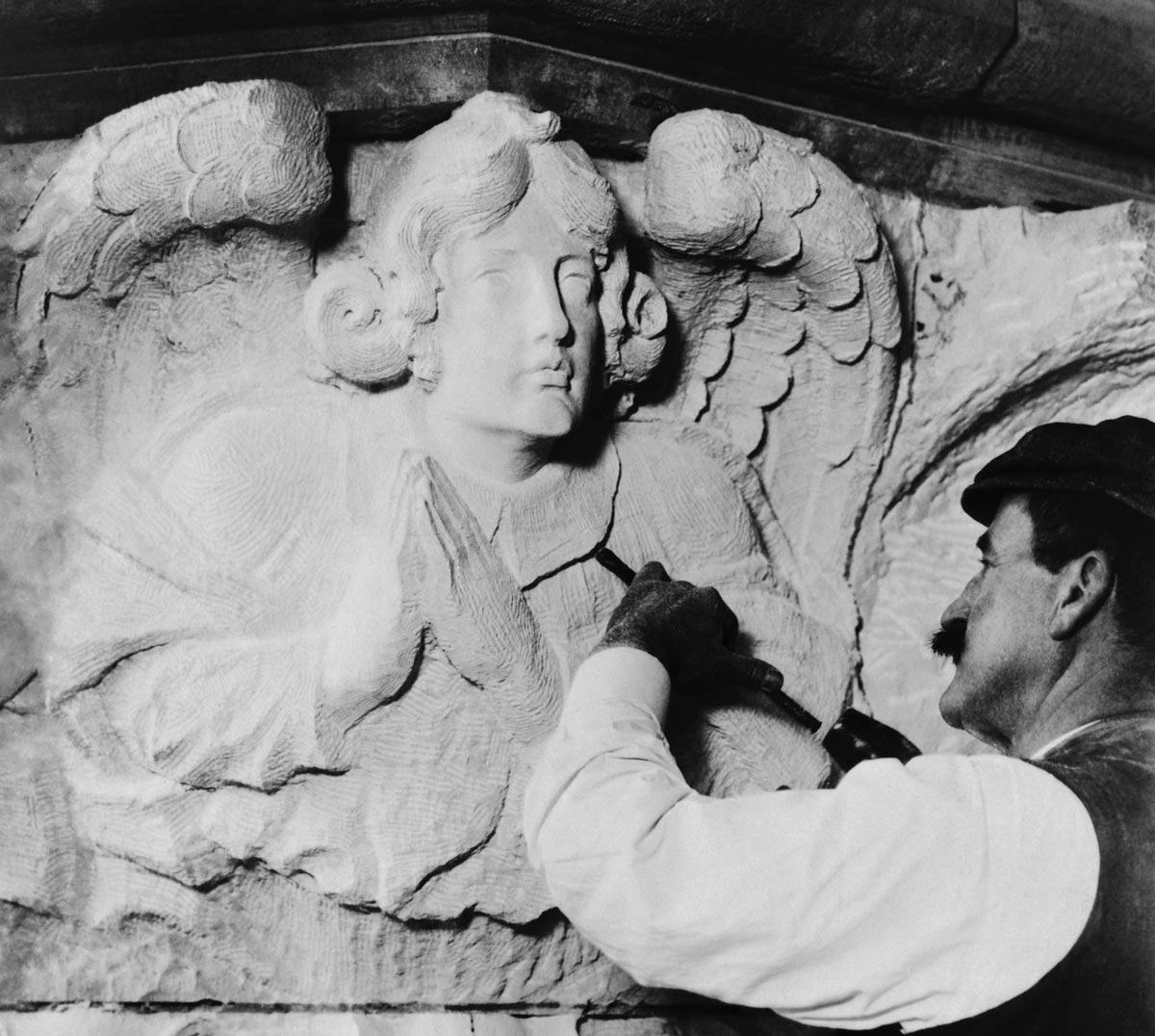

Image: The Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine.

As a child I was spellbound by the story of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City, designed to be one of the greatest churches in the world when it was begun in 1892. It is called Saint John the Unfinished: with decades still to come before it finally tops off, if ever it does, its oldest sections are antique, many times revised and repaired.

The official history says that the bell tower

cuts off "in mid-sentence," at about two-thirds of its intended height. The newer stone makes a strong contrast with the more weather worn parts of the West Front.

Changes in fashion and technique required revisions to the plan as it progressed. According to the tastes of the time, its first twenty years of construction followed a Byzantine style. In 1909, with Gothic Revival coming into fashion, a new architect was hired and the work so far was overhauled.

The original ambition for the church was that it be built using only medieval stonemasonry techniques, without steel or concrete. The stone arts were already in decline in the late Nineteenth Century, and now in the Twenty-First so few master masons remain that the bell tower may never finish the final stories of its utterance.

I was thinking about Joe Gould, and about Saint John the Unfinished, as I read Randall Hyde's "Write Great Code", Volumes 1 and 2.

They are voluminous indeed, at 450 and 630 pages, and aim to teach "Understanding the Machine" and "Thinking Low-Level, Writing High-Level". Yet they are only half of Hyde's project. In his introduction he promises Volume 3, "Engineering Software", and Volume 4, "Debugging, and Quality Assurance". He signs off at the end of Volume 2, published in 2006, with a chipper, "Congratulations on your progress thus far toward knowing how to write great code. See you in Volume 3."

His giant unfinished books reward a patient reader, but not so much as the reader hoped.

In the first volume, "Understanding

the Machine", Hyde's description of the memory bus and

the cache are thorough and clear. I finally understood, briefly while I

held it in my own memory, why certain sizes of struct are cached most

efficiently. Hyde explains instruction pipelining, out-of-order

execution, and other topics I had judged to be too magic for me. Now that I have read his section on addressing modes in x86 machine code, I can "see" through a C expression like array[i]->member to the machine code and the CPU, and I understand the true cost of virtual method invocations in C++ (especially when I combine what I learned about addressing modes with my new intuition about instruction pipelining). Hyde's chapter on floating-point representation is not the first treatment of

this topic I have read, but it is the first I have read to the end. I skipped, however, his tutorial on performing long-hand division in binary.

Volume 2, "Thinking Low-Level, Writing High-Level", is nicely targeted: "to teach you what you need to know to write great code without having to become an expert assembly language programmer." Some of the advice is sound: Fitting data structures to a cache line can make a measurable difference. Ensuring data is well-aligned in memory, and walking arrays in the proper order to maximize cache coherence, are worthwhile everyday optimizations.

Other advice in Volume 2 was probably silly when Hyde gave it in 2006, and is certainly silly now, only ten years later. For example, Hyde recommends that frequently-used local variables be declared before those used less frequently, to ensure that the most common accesses use smaller offsets. The smaller offsets potentially allow addressing modes that use shorter machine instructions. This may be true in the limit, but in my recent experience maintaining C code, I find that programmers who focus on such micro-optimizations would be better off taking a step back from the code—one can usually see greater inefficiencies when looking through a wider lens.

Whether this optimization advice is obsolete is a matter for debate, but much of the two volumes is indisputably outdated. Like Saint John's, the unfinished work of Randall Hyde needs revisions in its ground floors, even as the upper stories remain forever interrupted mid-sentence. Of the programming languages used in the book—C and C++, Pascal, BASIC, Delphi, and something called Kylix—only C and C++ are now common. He even cites Modula-2, which was already ancient Greek when Hyde published Volume 1 in 2004. The material's dustiness suggests it was already years old when it was finally printed.

Worse, the instruction set architectures that are the book's focus are 32-bit Intel assembly and 32-bit PowerPC. Those architectures were like the Byzantine style of their day: about to go out of fashion. A modern book would cover x86-64 and likely 64-bit ARM, discarding the now-rare PowerPC.

Had Randall Hyde never promised a four-volume monument, and instead set his sights on the smaller project he could finish, it would better endure. A merely competent pair of books does not benefit from the awesome hubris of the Cathedral of Saint John, or Joe Gould's pathos. Hyde would have been better off under-promising and over-delivering, like the rest of us mere craftspeople. Indeed, I hazard that he and his publishers might have invested in updating Volumes 1 and 2, if the unfinished volumes hadn't loomed over them.

In my line of work, the most famous unfinished work is Donald Knuth's The Art of Computer Programming.

Knuth began by writing a book about compiler design, completing a 3000-page handwritten manuscript over the years 1962-66. In the fifty years since, the original monolith has been split into a seven-volume project, treating comprehensively not only compiler design but nearly every aspect of computer science, computational linguistics, and discrete mathematics.

Only the first three volumes are finished, and changes in technology have required several overhauls of the work so far. The example assembly code in the published volumes is now long obsolete and will be (eventually) replaced with a 64-bit modern assembly language, if it is still modern by the time that effort comes to fruition.

Between the first and second publishings of Volume 2, the original typesetting technology became obsolete. In a notorious digression, Knuth spent ten years writing a new typesetting system called TeX. Knuth's typesetter introduced novel algorithms for the layout of figures, lines, and paragraphs. The scope of the work expanded to include a Turing-complete programming language, and TeX eventually became self-documenting: it is written in a style Knuth invented called "literate programming." The source code of TeX is both the program and the explanation of how it works. The explanation is typeset in TeX.

In the years Knuth spent developing TeX, its original implementation language "SAIL" became obsolete and he had to completely rewrite the typesetter in Pascal. The system was declared finished in 1989 and closed to enhancements. Because its rendering of equations is still unexcelled, it remains the standard for typesetting mathematics papers. The algorithms Knuth invented discover the most beautiful layout of a complex page, by considering all its aspects at once—its figures and equations, its many fonts, the rules of hyphenation and the desire to eliminate widows and orphans. His brilliant solutions are the basis of all publishing today.

Yet, completion of The Art of Computer Programming was only farther off.

Maybe Douglas Adams was thinking of Knuth, as much as he was thinking of himself, when he wrote in "So Long And Thanks For All The Fish":

One of the greatest benefactors of all lifekind was a man who couldn't keep his mind on the job at hand.

The problem was that he was far too interested in things which he shouldn't be interested in, at least, as people would tell him, not now.

So when his world was threatened by terrible invaders from a distant star, who were still a fair way off but traveling fast, he was sent into guarded seclusion by the masters of his race with instructions to design a breed of fanatical superwarriors to resist and vanquish the feared invaders, do it quickly and, they told him, "Concentrate!"

So he sat by a window and looked out at a summer lawn and designed and designed and designed, but inevitably got a little distracted by things, and by the time the invaders were practically in orbit round them, had come up with a remarkable new breed of superfly that could, unaided, figure out how to fly through the open half of a half-open window, and also an off switch for children.

Knuth, too, is one of our greatest benefactors. The things he built when he got distracted are foundational to modern computing. They'd be the life's work of lesser inventors. And his main opus, the unfinished book, towers above completed projects of littler ambition.

Knuth, now 77 years old, is not hurrying to complete his masterwork. Instead, he publishes it in smaller and smaller increments: Volume 4 was partly released in 2005, and further progress was published as Volume 4A in 2011. The seventh chapter alone of Volume 4 is planned as a series of releases called Volumes 4B, 4C, and 4D. I doubt they can be finished before Knuth is.

A final section of Chapter 7, according to Knuth's plan of work, will be headed "Herculean tasks".