Are the Six Senses True Reality, Or Not?

Dharma talk delivered at the Village Zendo, May 9, 2019.

I’m going to talk about mindfulness. And I’m going to begin by appearing to agree with the popular conception of mindfulness, then I will attack it as shallow and inconsistent with Buddhism. So, I hope you’re sitting down.

I recently read a research paper. It was from 2010 but it came across my radar recently. The title is, “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind,” and it’s rather nicely written. It begins:

Unlike other animals, humans spend a lot of time thinking about what is not going on around them, contemplating events that happened in the past, might happen in the future, or will never happen at all. Indeed, “stimulus-independent thought” or “mind wandering” appears to be the brain’s default mode.

There’s a lot in there. First of all, they call mind wandering, “stimulus-independent thought.” I’ve read other research papers that also support this idea that mind wandering is not usually stimulated by something that we actually experience in the world… You’re just walking along and regardless of what you’re doing, what you’re seeing, all of a sudden your mind starts wandering and it goes off in a direction that is motivated by your internal psychological processes. Whatever seeds of consciousness have been planted in you long ago, all of a sudden they sprout. It’s not like you’re reminded of something and that triggers mind wandering, mind wandering begins more often on its own. And this is the default thing that our minds do. When we’re not doing anything in particular, when we have no particular motive, we take the opportunity to daydream. And that daydreaming is very often worrying.

Although this ability is a remarkable evolutionary achievement that allows people to learn, reason, and plan, it may have an emotional cost. Many philosophical and religious traditions teach that happiness is to be found by living in the moment, and practitioners are trained to resist mind wandering and “to be here now.” These traditions suggest that a wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Are they right?

So, here’s the study. The researchers made an iPhone app and invited people to install it on their phones, a few thousand volunteers did so. When they installed the app, it asked them, “When do you normally go to sleep and wake up?” And then at random points during their waking hours, three times a day, the app pinged them. The volunteers were supposed to open the app and answer three questions.

Number one: What are you doing? Are you working, sleeping, watching TV, taking care of kids, having sex, exercising, walking?

Number two: What is your mood? Are you feeling good, bad or neutral?

Number three: Is your mind wandering? If so, is it wandering to negative thoughts, neutral thoughts, positive thoughts or is your mind not wandering, are you paying attention to what you’re doing?

They got a few thousand volunteers. Each of them answered these three questions at three random points in the day. Usually for a few days before they gave up. But it was enough for them to find some outcomes. So, what did they find?

First of all, the mind wanders about half of the volunteers' waking lives. Forty-seven percent of waking hours. When the app pops open, the volunteers say that their minds are wandering. That statistic, about half of the time we don’t know where we are, is consistent with other papers that I read. The other interesting thing is that what people are doing has very little effect on their mood. Whereas mind wandering has an enormous effect. So, to a small extent, people are more likely to be in a bad mood when they’re working and a good mood when they’re exercising or eating, but that is a very small effect. Whereas people are much, much more likely to be in a bad mood if their minds are wandering and they’re having negative thoughts. If their minds are wandering and they have neutral thoughts, that also puts them in a bad mood, though less so. Mind wandering with positive thoughts does not put you in a good mood. The best mood that we’re in is when we are paying attention to what we are doing.

The other interesting thing is that whether our minds are wandering or not, is not particularly affected by activity. So, whether you’re working or walking or exercising, you’re about equally likely to have your mind wander. And when your mind wanders, you’re about equally likely to have negative, neutral or positive thoughts no matter what you’re doing. So, it’s not as if you work, then you’re bored, you start thinking, you start thinking bad things. No. The mind just seems to have a mind of its own. Regardless of what you’re doing, it just goes off and it decides whether to have negative, neutral or positive thoughts.

I’m pleased to report that the one exception to all of these trends is having sex. If volunteers are having sex and their phone pings them and says, “I have three questions for you,” if they say, “I’m having sex,” they will also say, “I’m in a good mood and my mind is not wandering.” If we could just have sex all the time, Buddhism might not be so necessary.

But here’s the really interesting outcome of this study, which is that although negative mood causes mind wandering to a small extent, the huge effect, the thing that swamps everything else they found is that mind wandering toward bad thoughts causes a bad mood. All of the other causal arrows are very weak. The main thing that happens is that our minds start wandering. We think negative thoughts and then we are in a bad mood. And they can tell what causes what because if the app opens and you say, “My mind is wandering and I’m thinking negative thoughts,” that tends to mean that a few hours later when the app opens again, you say, “I’m in a bad mood.” So, first bad thoughts, then bad mood. All of the other causal arrows are much weaker. So, it just seems like the mind has a mind of its own.

I was reminded of this, the worst mind wandering, spiraling, negative thoughts experience that I had over the last week was in Cleveland, when I was there for a software conference. I gave a big tech talk on Friday morning and so Thursday night I decided to rehearse it a few times before the next morning. I hadn’t been taking it very seriously because I’d given this talk at a few conferences before, so I thought, after dinner I’ve got a couple hours before I go to sleep, I better just run through it. So, I opened my laptop. In my Airbnb, I put the laptop on the counter next to my dirty dishes and I just ran through this talk once. And it took me 40 minutes, and I thought, ‘Oh, shit.’ I’ve only got a 30 minute slot and they’re very strict about this. And I only have a few hours before I need to go to sleep. How am I going to rehearse this? What am I going to do, talk faster? Cut material? It’s so late in the day to be cutting a third of this talk out of it. I started spiraling out, like, ‘Oh, God, this is going to be a disaster’ and ‘I’m such an idiot for thinking that I didn’t need to rehearse this until now.’

And then I caught myself spiraling, like, ‘This is not a useful thing to do right now.’ So, I internally shouted, ‘Stop.’ Which is something I do pretty often; it’s a habit I developed. When I hear myself criticizing myself, or worrying, I just internally say, ‘Stop.’ Last year, I more often said, ‘Fuck.’ I appear to be mellowing unintentionally. I’ll try to get back on track. So, I said, ‘Stop,’ to myself and I focused on what I could actually do, which is to rehearse this talk. And I cut a couple of slides. As I re-familiarized myself to the material, I remembered how to say things concisely and after a few run-throughs I was down to half an hour. And the next day the talk went great. I had a huge room full of more than 500 people and I delivered the presentation smoothly in 28 minutes and 14 seconds. Golden.

So, we know that this works. That preventing the mind from wandering, especially wandering to bad thoughts, it’s a good way to stop worrying and to feel at peace. We feel best when we are paying attention to this, here, now. And that’s why meditation is our main tool. We deliberately put ourselves into a situation where the brain’s default mode wants to turn on. You’re sitting still, you’re facing a wall, you’re not entertained by anything, you’ve got nothing to accomplish. The mind naturally daydreams. So, we put ourselves into this training situation in which our mind is tempted to wander, and we bring it back and bring it back, over and over again, so that that becomes a habit. So that as we’re going through our daily lives, we maybe spend a little less time daydreaming.

The main tool, that I use at least, for bringing myself back to this moment, is to pay attention to the five senses, to the sensation of my butt on the cushion, my breath going in and out, the sight of the wall in front of me. In Buddhism, we say that there are not just five but six senses. That the thoughts that run through our heads are also a sense. And I think that this sense is a lot like sound, in the way that it kind of, it can’t be shut off, you can’t close your ears. And it comes and goes.

So, I try to treat thoughts in the same way I treat sounds when I sit. When I sit and I hear a truck go by, I let the sound come and go. I don’t concentrate on it and I don’t try to shut it out. It’s the same with a thought that comes and goes. I don’t follow that thought with the next thought. I don’t tell myself a story. I don’t analyze it or make a plan. But at the same time, I don’t think that it’s very helpful to try to prevent thoughts from arising in the first place, to try to screw them down with all my might. Typically, that just ends up causing a spring back, where the thoughts come back with a vengeance. So, I just let them come in and out, just like sounds.

When I’m really starting to get into the groove of zazen sometimes, I hear the thoughts come disorderly at random, sort of like the sound of somebody who talks in their sleep. If you’ve heard that, they’ll just say like, ‘You forgot the fork.’ ‘Redact.’ ‘I can’t hear you.’ I think that’s what thoughts sound like when the default mode is offline. When the logical progression of planning and figuring it out is gone and the thoughts are just coming automatically. I sometimes hear that when I’m meditating, thoughts just coming and going without any meaning or any emotion.

So far, this sounds like a lot of popular mindfulness, like iPhone app mindfulness. I’m even giving you a story that sounds like that. ‘I succeeded in my professional endeavors because I’m a meditator.’ And we know that this works, right? All of the studies of mindfulness based stress reduction show what we would expect, that people who know how to meditate, their blood pressure is lower and they have less cortisol in their blood streams, right? So far, so good. But this idea of mindfulness, its origin has a very different character.

A lot of what we talk about when we talk about mindfulness comes from the Satipatthana Sutta. Sati is the word that has been translated as mindfulness. And patthana is the foundation, so it’s the Foundation of Mindfulness Sutra in the old Pali Canon, the first stuff that ever got written down. Sati, this word also has a sense, not just of paying attention, but also of recalling. Recalling what we really are. Recalling that our delusions are delusions. Recalling the true nature of this reality.

And the key difference here, according to what I’ve read, between the popular mindfulness attitude and what Buddha described in the Satipatthana Sutta, is that when we pay attention to our existence we also clearly comprehend its true nature. Here’s a quote:

Buddha commanded his monks to live contemplating the body as the body, ardent, clearly comprehending and mindful, having overcome, in this world, greed and sadness.

Contemplate the body as the body. In other words, not our delusions about the body. Not the body as being me, but as it actually is. As an ever-changing, interdependent, impermanent bit of the whole energy field. Just like a wave in the whole mish-mosh. Not as a special important thing that I own.

He commands his monks, who are us, these bodhisattvas, commands us to contemplate ardently, clearly comprehending the body and feelings and thoughts and ideas. All of these aspects of our existence as we experience it. And the question is, what does he mean by clearly comprehending? What is a correct view of what we’re experiencing here, versus what might be incorrect? And again, this is according to what I’ve read, the clear comprehension of what we’re experiencing is that everything we experience is marked by non-self, by impermanence and unsatisfactoriness.

So, if we comprehend our thoughts, for example; they come and go. How do we see these three marks in our thoughts? If you are mindful of your thoughts over time, if you’re interrupting these trains of thought that you have, you’ll see that they’re sort of random. They seem to come from random directions. They don’t have any sort of consistent story to them. They’re not like a person talking to myself. They’re just kind of like, processes. There’s no self to them. And if you see that clearly over time you come to understand that your thoughts do not have a self.

You also see how thoughts change constantly. One moment I believe I’m unprepared to give my talk tomorrow, the next minute I realize, ‘Oh, I’ve got this.’ Right? And the next minute I forgot I was thinking about that entirely and I’m just thinking about something else. Thoughts are impermanent.

And finally, notice how sometimes you have a nice thought that makes you feel good. But if you attach to that nice thought, like, ‘I got this. I’m going to be a great public speaker. I’m going to nail it tomorrow.’ Thinking that and depending on that to make me feel happy is doomed, because the next minute I’m going to start worrying again. Depending on good thoughts, good beliefs, in order to enjoy our lives, is doomed to failure. It’s unsatisfactory. And we can apply these three marks to everything that we experience.

This is the right mindfulness practice of the old sutras. And you can see that it’s not limited to just, ‘I’m going to learn mindfulness and that’s going to make me happy so then I’ll be a better worker.’ It goes way beyond that. It goes to seeing the true reality of what we are experiencing, and thereby liberating ourselves from being attached to it. And being mistaken about what it really is. When we see what our lives are, then we can really live them as they are.

So, that’s the old sutra’s description of Sati, of mindfulness. But this is not how we tend to approach it in Zen. This systematic, philosophical, clearly explained way. Zen tends not to describe true reality, but to express from it. I find that a good way to understand why Zen expression comes across so nuts sometimes. It’s not describing reality to me, it’s talking from reality.

For example, here’s a koan. You though I’d never get here, right?

A monk asked Ummon, “What is the body of reality?"

Ummon said, “Not contained in six.”

This was tough for me. It took me a long time and it was an insight when I got through it.

I understand what the monk is asking. What is the body of reality? And I thought I understood Ummon’s answer, ‘Not contained in six.’ I know that this is the six senses. And so I kept trying to answer this koan by saying, ‘Well, of course the body of reality is not contained in the six senses.’ The body of reality is everything, so the six senses are contained in it, right? But that’s so far off. You can probably hear it, right? As soon as I start saying, ‘The body of reality is the big one. The six senses are the little one. This is the outer circle and this is the inner circle and I can slice it up like this,’ I failed.

The body of reality is not sliced up this way. Not only does nothing contain it, it doesn’t contain anything. The body of reality is the six. The six is the body of reality. But neither are they the same and neither are they different.

Do you hear the hum of the stereo system right now? We can practice with this in this way. I say, it’s the sound of the stereo system right now. But what if it’s not the sound of the stereo system? What if it’s just sound? What if I’m not hearing it? What if it just is? And then, what if there’s no idea that it’s the sound at all, just woosh. Not separate from the hearer, not heard. Not sounding, just woosh. That’ll happen sometimes if you’re sitting zazen. Happens more often if you sit long retreats or zazenkais. Or when we sit together and we motivate each other to really make the effort, where these separations and categories will just drop away for the moment and we’ll be the body of reality, as we always are.

The sort of sad thing is, no matter how much we want it, most of the time when it happens, we forget it did. We want to have had the achievement and then be able to cling to it by remembering that we had it. And bad news, it happens all the time and we forget it. You’re walking up the stairs, you’re standing in line, you’re concentrating on your job and you’re there. The body of reality is you and your activity, and it was so beautiful that you completely forget. But that’s okay. Keep making the effort to have this insight, to see that this true body of reality, this self-less, impermanent thing must not be clung to. That is real; that is real life. And when we practice this way, this is the body of reality.

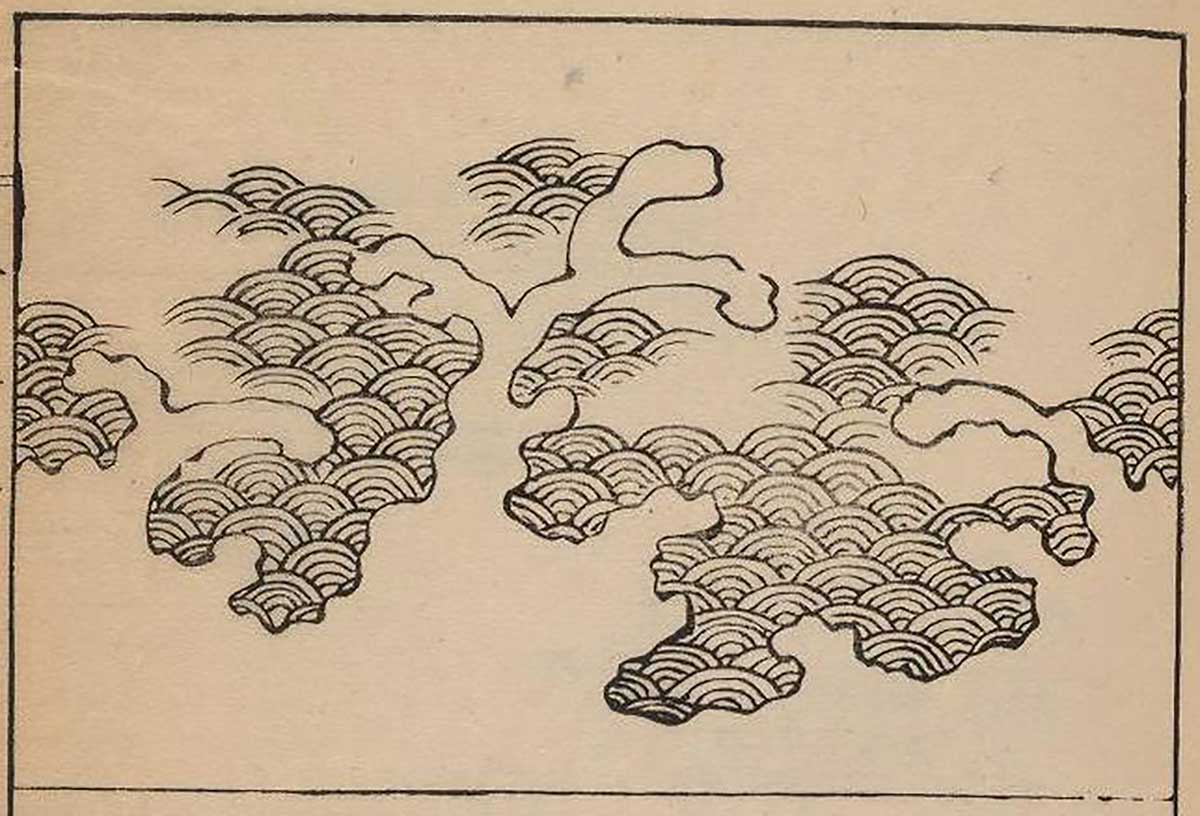

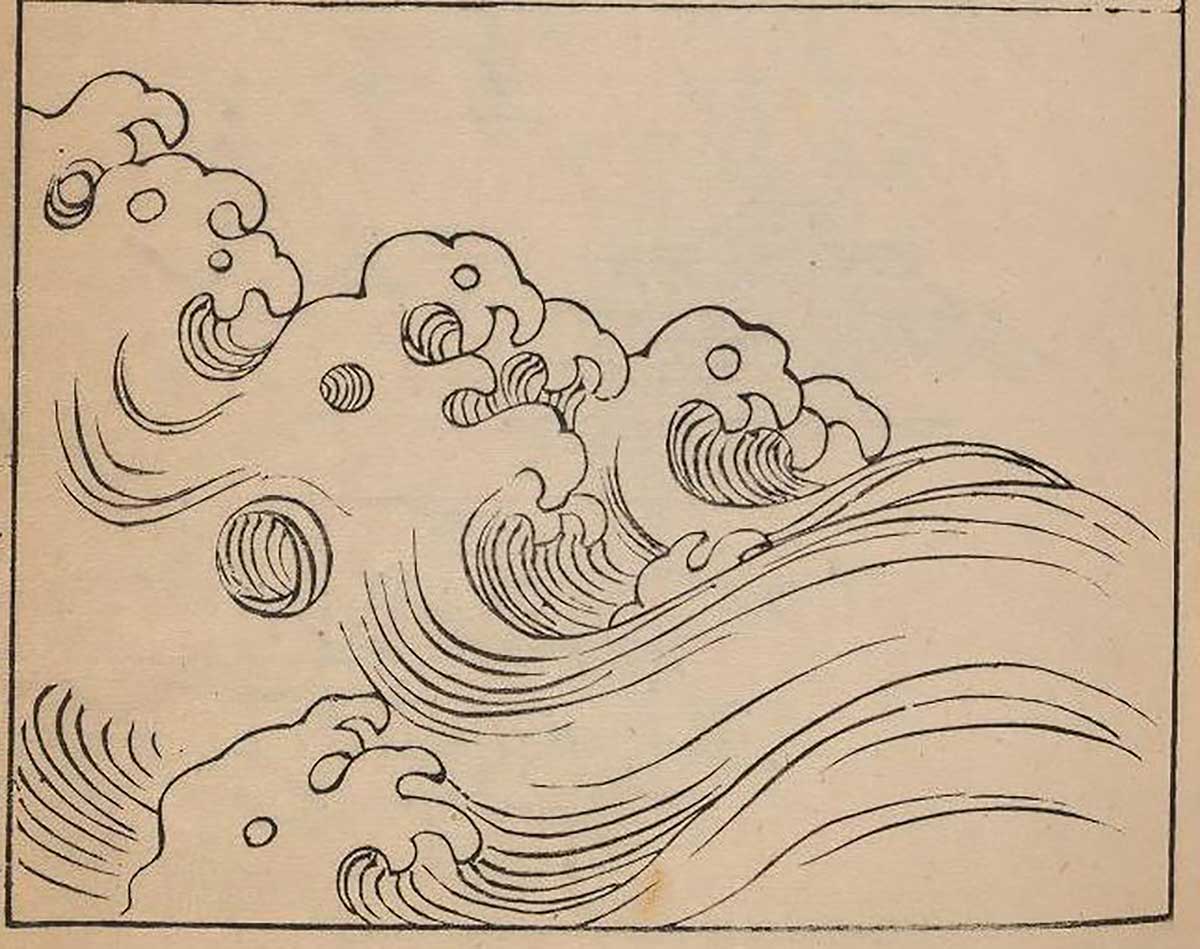

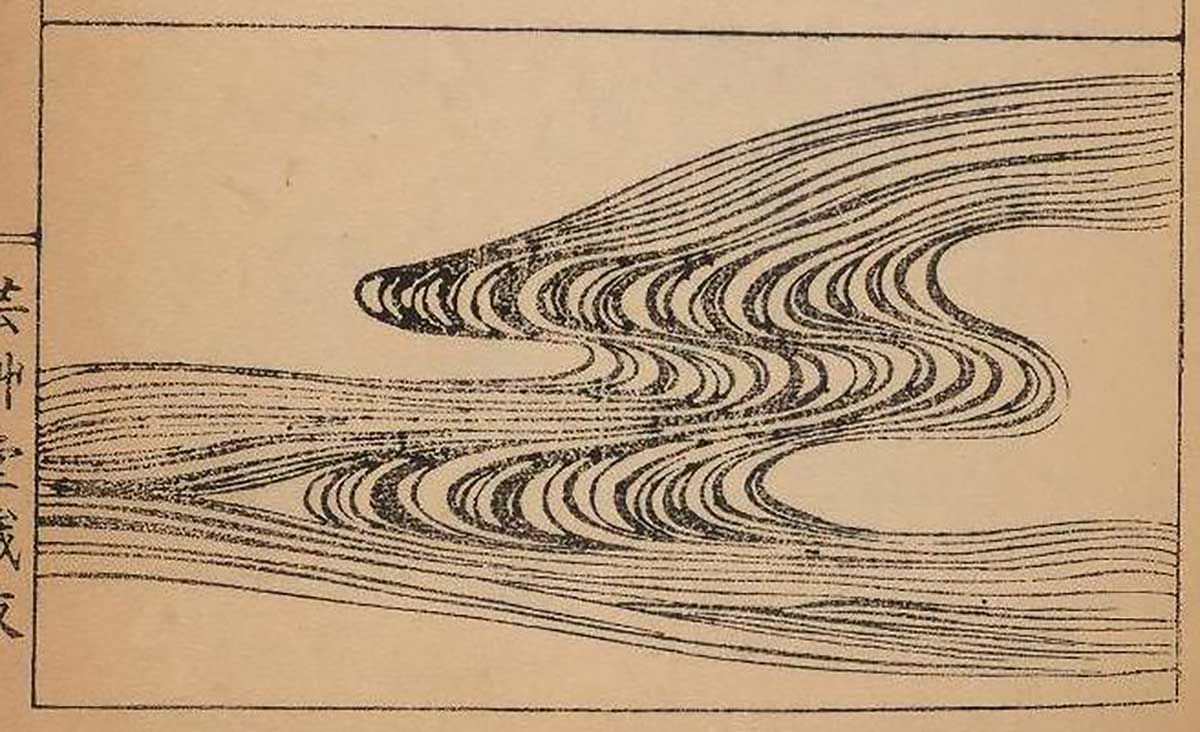

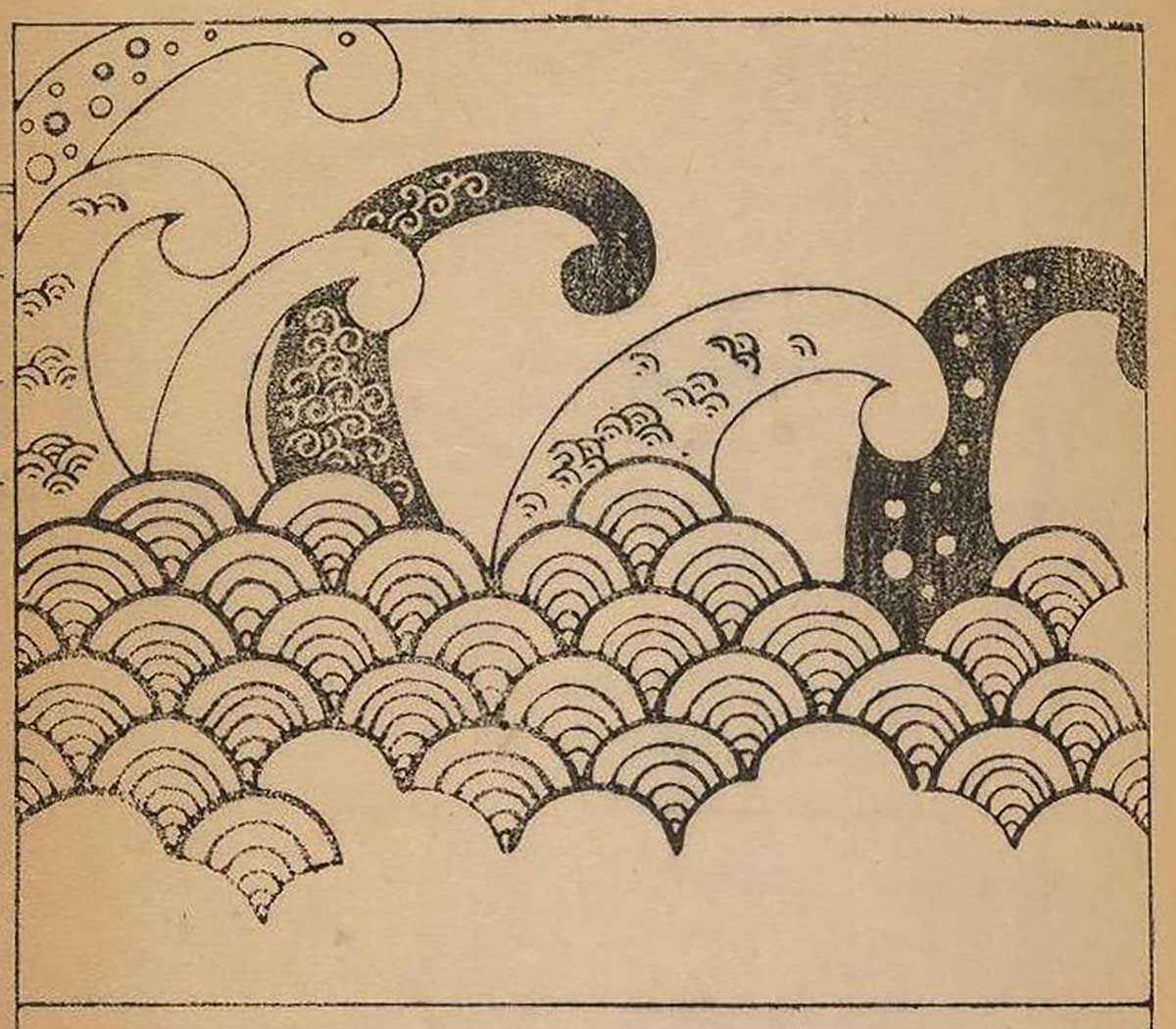

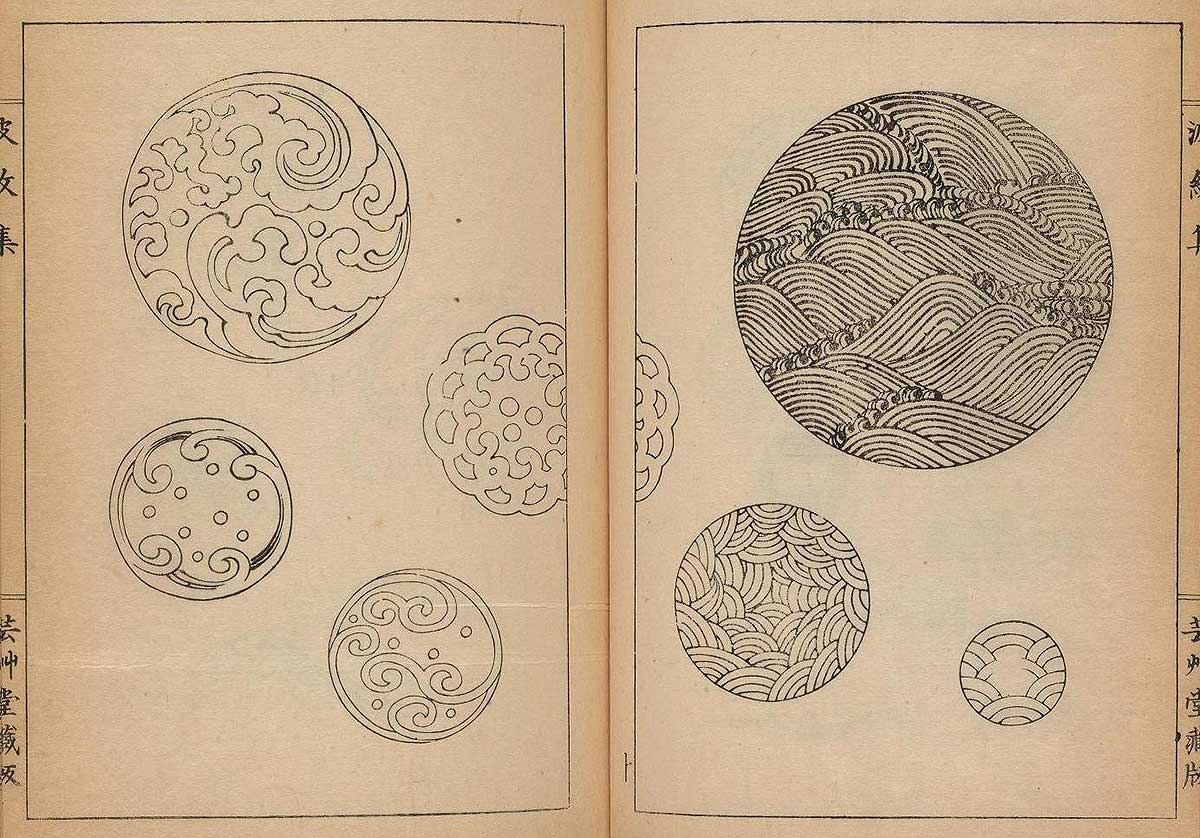

Images: Hamonshu: A Japanese Book of Wave and Ripple Designs (1903)