Reading Ann Gleig's "American Dharma"

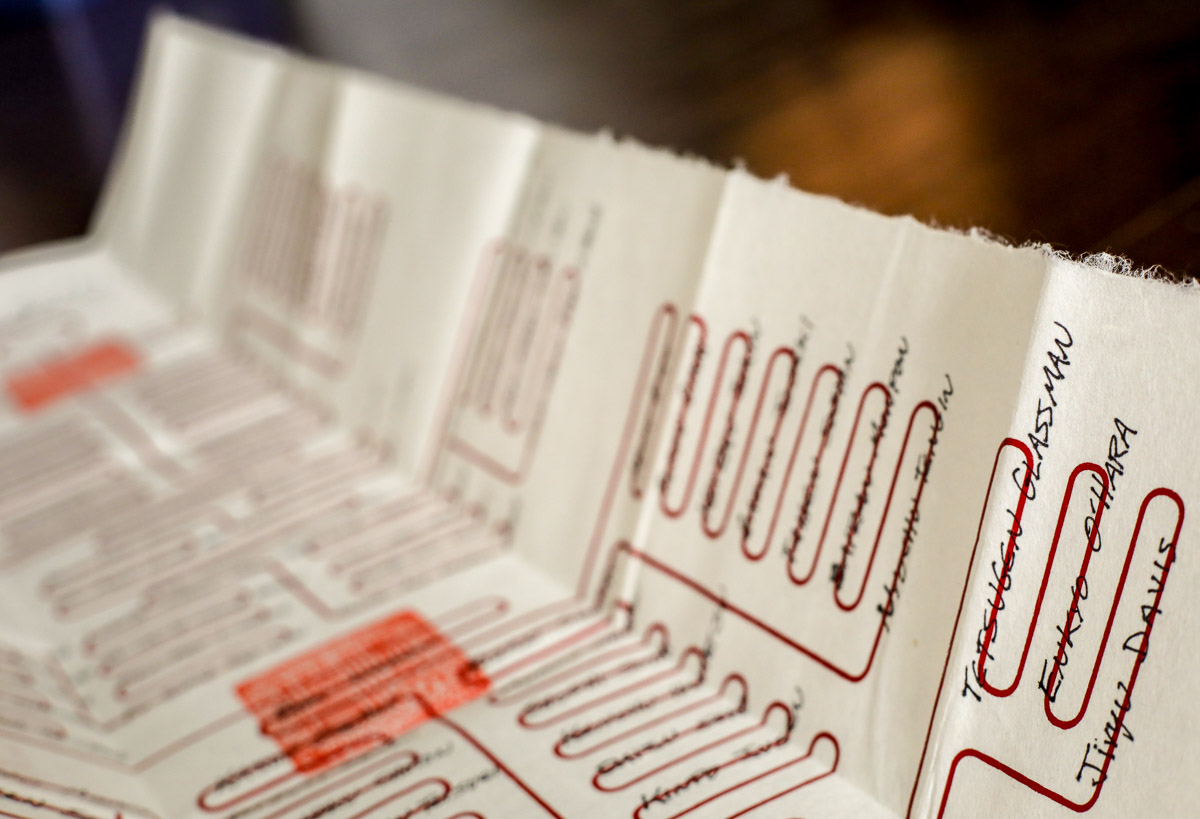

In 2006, I promised to uphold the Zen ethical precepts, and I received the dharma name Jiryu from my teacher. Late the night before, as part of the ritual, I created a chart of my Buddhist lineage. At the top I wrote the name of the historical Buddha, and beneath him his student Mahakasyapa, then his student, and so on. Near the bottom I reached the name of Taizan Maezumi, who came from Japan to found the Zen Center of Los Angeles in 1967, then his student Bernie Tetsugen Glassman, and finally his student Pat Enkyo O’Hara, who is my teacher. That night, after I had finished, Enkyo wrote my name beneath hers. A winding red “blood line” passed through each name from teacher to student, travelling through Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and American names, and finally looping from my name back up to the Buddha to create a continuous cycle.

When Zen students like me write our lineage charts, we express our commitment to an ancient tradition, and we claim that our practice is legitimate because this chain of teachers certifying students is unbroken. But how traditional are we, really? In some ways my community, the Village Zendo, really is traditional. We sit still with our legs crossed, like the Buddha did, and we burn incense and chant the names of Bodhisattvas, like Buddhists do in China and Japan. In other ways we are radical. My teacher Enkyo is the first woman in that long line of teachers, and only the second white person. Unlike traditional Buddhists, we make little distinction between lay and priest: priests have jobs and apartments like laypeople, laypeople meditate and study advanced texts like priests. Practically none of us was born in a Buddhist family; we came to the practice as adults.

To better understand my community’s place in the history of Buddhism I read Ann Gleig’s new book American Dharma. Gleig used the writings of contemporary Buddhists in North America, and interviews with them, to describe how Buddhism is changing here as a new generation takes over. She focuses on the type of Buddhism she calls “meditation-based convert Buddhism.” In the 20th Century, practitioners of this type stripped down and modernized Buddhism. They emphasized meditation, jettisoned most of the Asian rituals and beliefs, and claimed to recover the original meaning of Buddha’s teaching. In the 21st Century we are changing again, in a variety of directions. Some groups are becoming more politically active and more diverse, reaching out to Asian-Americans and other people of color. Some are reckoning with the racism expressed in white Buddhists’ rejection of Asian tradition. On the other hand, some are rejecting tradition more thoroughly, or even dropping the name “Buddhism.”

I had thought that my own practice at the Village Zendo was comparatively traditional. We take Japanese names, chant in Japanese, and we are regularly re-certified as a temple in the Soto school, headquartered in Kyoto. I had made the mistake of viewing our Japanese tradition as old and slowly-changing, and I thought that any innovations in Zen were American. I didn’t understand how much innovation had already preceded the transmission of Zen from Japan to the US. I learned from Gleig that “Buddhist modernism” began in Asia in the 19th Century. The Buddhism we received from Asia had already been transformed by Asians—it was they who began shifting the emphasis from ritual to meditation, and who claimed that Buddha was a scientist of the mind.

There is a strong influence of Western psychotherapy in our Zen teachings. Sometimes I try distinguish the two, at other times I see them as overlapping regions of a larger field of inquiry. Gleig looks at this tension from an interesting angle. She recounts the recent history of sexual harassment and assault by some male Zen teachers. These incidents have made us question the way we’re adapting Zen to the West. It seems there is something wrong with how we train teachers and structure communities which has allowed these predators to do so much damage, so we have turned more strongly toward Western psychology for answers. Sometimes when we add more psychology to our practice we just replace traditional Buddhism, but ideally we bring the two approaches into dialog.

Gleig ends her book with a discussion of whether American dharma is modern, postmodern, ultramodern, or some other category. The question is worthwhile but difficult, and I feel fortunate that it isn’t my job to decide. I have different questions. I want to better understand my place and my sangha’s place on some axes along which Buddhists vary: How traditional or innovative are we? How diverse? How activist? How much do we focus on meditation versus holistic practice? How connected are we with Asian or Asian American Buddhists?

The book opened my eyes, especially regarding how innovative or traditional we are. My idea of “traditional” was naïve, and now I see more clearly the construction of my view of traditional Zen. I expect I’ll be more tolerant of innovation, seeing how the way I practice today is already more innovative than I thought.

The other big value I gained from the book is seeing the menu of options for an American Buddhist sangha. Learning about other sanghas’ recent directions, I’m thinking more critically about how I practice, and how I influence the practice of my sangha. I’m more aware of what choices other sanghas have made, and whether I want to avoid their path or emulate it.

Further reading:

- American Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Modernity, by Ann Gleig

- Gleig’s article “The Shifting Landscape of Buddhism in America” in Lion’s Roar magazine

- Podcast interview with Gleig, hosted by Natasha Heller

- Gesshin Claire Greenwood’s guide to reading American Dharma, “How to Hack an Academic Book”