Grok the GIL: Write Fast and Thread-Safe Python

(Cross-posted from Red Hat’s OpenSource.com.)

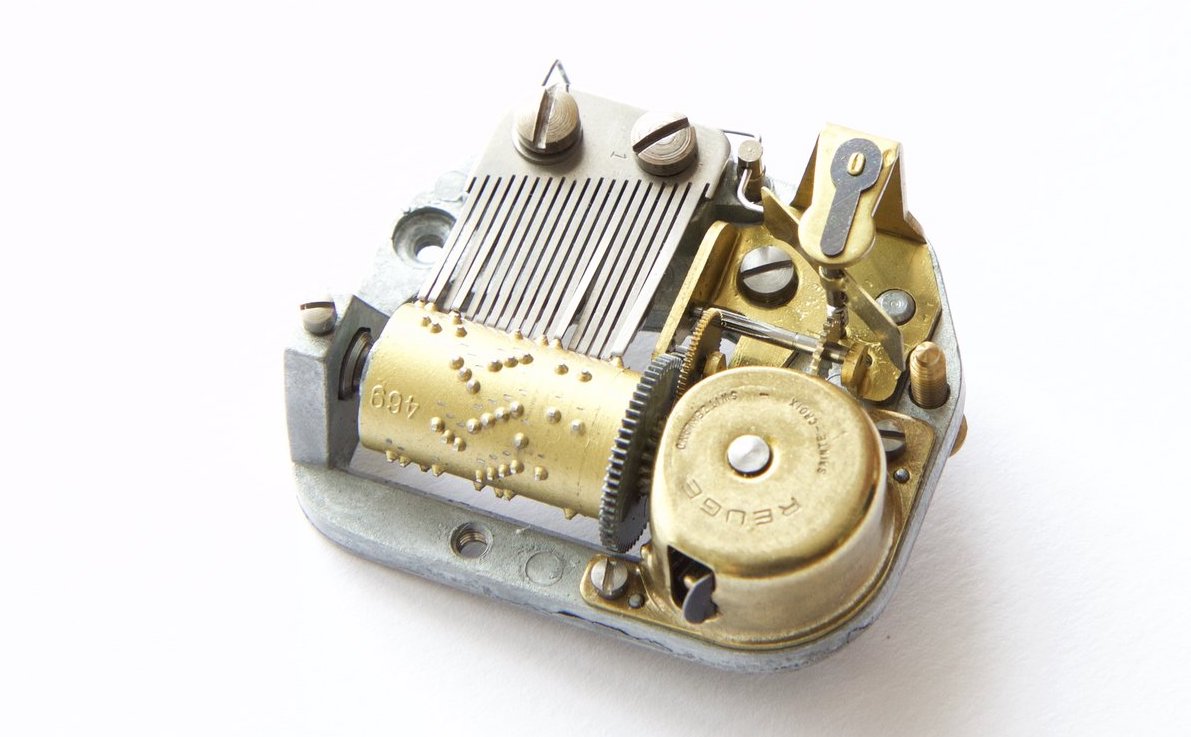

When I was six years old I had a music box. I’d wind it up, and a ballerina revolved on top of the box while a mechanism inside plinked out “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” The thing must have been godawful tacky, but I loved it, and I wanted to know how it worked. Somehow I got it open and was rewarded with the sight of a simple device, a metal cylinder the size of my thumb, studded so that as it rotated, it plucked the teeth of a steel comb and made the notes.

Of all a programmer’s traits, curiosity about how things work is the sine qua non. When I opened my music box to see inside, I showed that I could grow up to be, if not a great programmer, then at least a curious one.

It is odd, then, that for many years I wrote Python programs while holding mistaken notions about the Global Interpreter Lock, because I was never curious enough to look at how it worked. I’ve met others with the same hesitation, and the same ignorance. The time has come for us to pry open the box. Let’s read the CPython interpreter source code and find out exactly what the GIL is, why Python has one, and how it affects your multithreaded programs. I’ll show some examples to help you grok the GIL. You will learn to write fast and thread-safe Python, and how to choose between threads and processes.

(And listen, my dear pedantic reader: for the sake of focus, I only describe CPython here, not Jython, PyPy, or IronPython. If you would like to learn more about those interpreters I encourage you to research them. I restrict this article to the Python implementation that working programmers overwhelmingly use.)

Behold, the Global Interpreter Lock #

Here it is:

static PyThread_type_lock interpreter_lock = 0; /* This is the GIL */

This line of code is in ceval.c, in the CPython 2.7 interpreter’s source code. Guido van Rossum’s comment, “This is the GIL,” was added in 2003, but the lock itself dates from his first multithreaded Python interpreter in 1994. On Unix systems, PyThread_type_lock is an alias for the standard C lock, mutex_t. It is initialized when the Python interpreter begins:

void

PyEval_InitThreads(void)

{

interpreter_lock = PyThread_allocate_lock();

PyThread_acquire_lock(interpreter_lock);

}

All C code within the interpreter must hold this lock while executing Python. Guido first built Python this way because it is simple, and every attempt to remove the GIL from CPython has cost single-threaded programs too much performance to be worth the gains for multithreading.

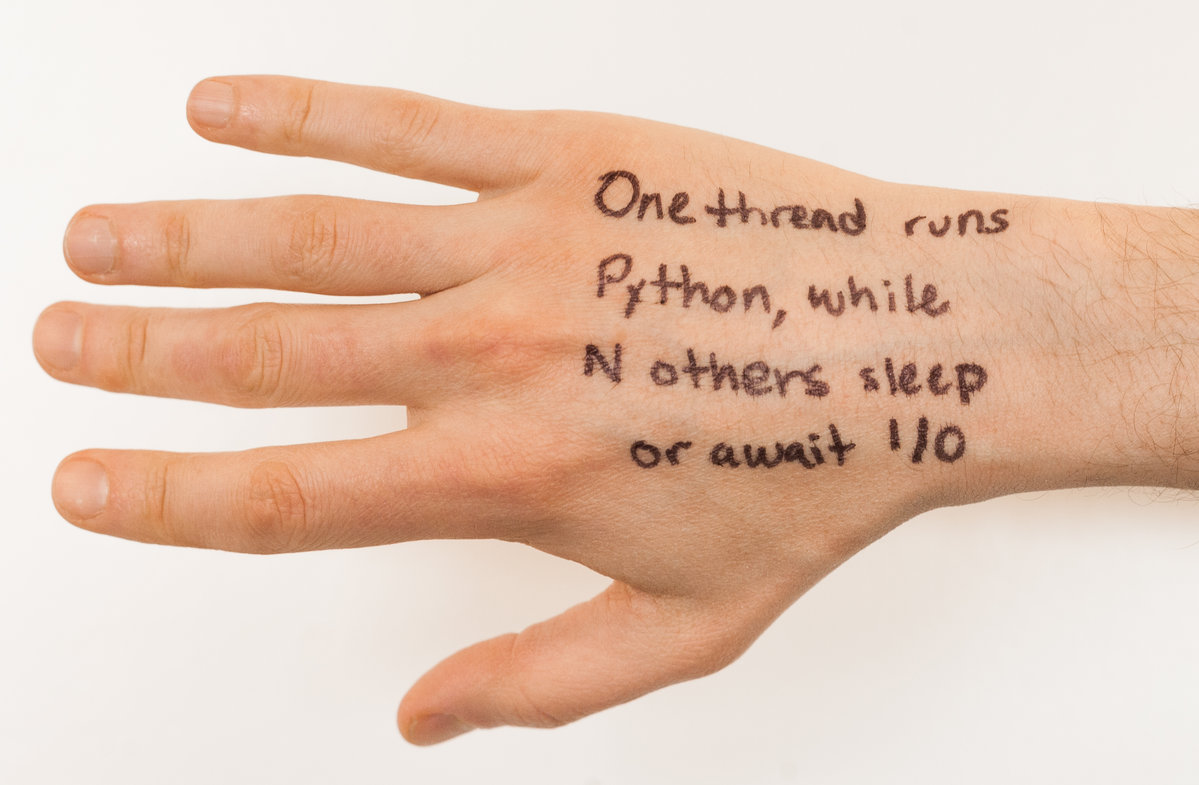

The GIL’s effect on the threads in your program is simple enough that you can write the principle on the back of your hand: “One thread runs Python, while N others sleep or await I/O.” Python threads can also wait for a threading.Lock or other synchronization object from the threading module; we shall consider threads in that state to be “sleeping”, too.

When do threads switch? Whenever a thread begins sleeping or awaiting network I/O, there is a chance for another thread to take the GIL and execute some Python code. This is “cooperative multitasking.” CPython also has “preemptive multitasking”: If a thread runs uninterrupted for 1000 bytecode instructions in Python 2, or runs 15 milliseconds in Python 3, then it gives up the GIL and another thread may run. Think of this like “time slicing” in the olden days when we had many threads but one CPU. We shall discuss these two kinds of multitasking in detail.

Think of Python as an old mainframe: many tasks share one CPU.

Cooperative multitasking #

When it begins a task, such as network I/O, that is of long or uncertain duration and does not require running any Python code, a thread relinquishes the GIL so another thread can take it and run Python. This polite conduct is called cooperative multitasking, and it allows concurrency: many threads can wait for different events at the same time.

Say that two threads each connect a socket:

def do_connect():

s = socket.socket()

s.connect(('python.org', 80)) # drop the GIL

for i in range(2):

t = threading.Thread(target=do_connect)

t.start()

Only one of these two threads can execute Python at a time, but once it has begun connecting, it drops the GIL so the other thread can run. This means that both threads could be waiting for their sockets to connect concurrently. This is a good thing! They can do more work in the same amount of time.

Let us pry open the box and see how a Python thread actually drops the GIL while it waits for a connection to be established, in socketmodule.c:

/* s.connect((host, port)) method */

static PyObject *

sock_connect(PySocketSockObject *s, PyObject *addro)

{

sock_addr_t addrbuf;

int addrlen;

int res;

/* convert (host, port) tuple to C address */

getsockaddrarg(s, addro, SAS2SA(&addrbuf), &addrlen);

Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS

res = connect(s->sock_fd, addr, addrlen);

Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS

/* error handling and so on .... */

}

The Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS macro is where the thread drops the GIL, it is simply defined as:

PyThread_release_lock(interpreter_lock);

And of course Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS reacquires the lock. A thread might block at this spot, waiting for another thread to release the lock; once that happens, the waiting thread grabs the GIL back and resumes executing your Python code. In short: While N threads are blocked on network I/O or waiting to reacquire the GIL, one thread can run Python.

Below, we’ll see a complete example that uses cooperative multitasking to quickly fetch many URLs. But before that, let us contrast cooperative multitasking with the other kind of multitasking.

Preemptive multitasking #

A Python thread can voluntarily release the GIL, but it can also have the GIL seized from it preemptively.

Let’s back up and talk about how Python is executed. Your program is run in two stages. First, your Python text is compiled into a simpler binary format called bytecode. Second, the Python interpreter’s main loop, a function mellifluously named PyEval_EvalFrameEx, reads the bytecode and executes the instructions in it one by one.

While the interpreter steps through your bytecode it periodically drops the GIL, without asking permission of the thread whose code it is executing, so other threads can run:

for (;;) {

if (--ticker < 0) {

ticker = check_interval;

/* Give another thread a chance */

PyThread_release_lock(interpreter_lock);

/* Other threads may run now */

PyThread_acquire_lock(interpreter_lock, 1);

}

bytecode = *next_instr++;

switch (bytecode) {

/* execute the next instruction ... */

}

}

By default the check interval is 1000 bytecodes. All threads run this same code and have the lock taken from them periodically in the same way. In Python 3 the GIL’s implementation is more complex, and the check interval is not a fixed number of bytecodes but 15 milliseconds. For your code, however, these differences are not significant.

Thread safety in Python #

Weaving together multiple threads requires skill.

If a thread can lose the GIL at any moment, you must make your code thread-safe. Python programmers think differently about thread safety than C or Java programmers do, however, because many Python operations are “atomic”.

An example of an atomic operation is calling sort() on a list of primitive objects like numbers or strings. A thread cannot be interrupted in the middle of sorting, and other threads never see a partly-sorted list, nor see stale data from before the list was sorted.

Atomic operations simplify our lives, but there are surprises. For example, += seems simpler than sort(), but += is not atomic! How can you know which operations are atomic and which are not?

Consider this code:

n = 0

def foo():

global n

n += 1

We can see the bytecode to which this function compiles, with Python’s standard dis module:

>>> import dis

>>> dis.dis(foo)

LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (n)

LOAD_CONST 1 (1)

INPLACE_ADD

STORE_GLOBAL 0 (n)

One line of code, n += 1, has been compiled to four bytecodes, which do four primitive operations:

- load the value of

nonto the stack - load the constant 1 onto the stack

- sum the two values at the top of the stack

- store the sum back into

n

Remember that, every 1000 bytecodes, a thread is interrupted by the interpreter taking the GIL away. If the thread is unlucky this might happen between the time it loads the value of n onto the stack and when it stores it back. It is easy see how this leads to lost updates:

threads = []

for i in range(100):

t = threading.Thread(target=foo)

threads.append(t)

for t in threads:

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print(n)

Usually this code prints “100”, because each of the 100 threads has incremented n. But sometimes you see 99 or 98, if one of the threads’ updates was overwritten by another.

So, despite the GIL, you still need locks to protect shared mutable state:

n = 0

lock = threading.Lock()

def foo():

global n

with lock:

n += 1

What if we were using an atomic operation like sort instead?:

lst = [4, 1, 3, 2]

def foo():

lst.sort()

This function’s bytecode shows that sort cannot be interrupted, because it is atomic:

>>> dis.dis(foo)

LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (lst)

LOAD_ATTR 1 (sort)

CALL_FUNCTION 0

The one line compiles to three bytecodes:

- load the value of lst onto the stack

- load its sort method onto the stack

- call the sort method

Even though the line lst.sort() takes several steps, the sort call itself is a single bytecode. If we inspect the CPython source for sort we see it’s a C function that doesn’t call any Python code or drop the GIL, so long as we haven’t provided a Python callback for the key parameter, or added any objects with custom __cmp__ methods. Thus, there is no opportunity for the thread to have the GIL seized from it during the call.

We could conclude that we don’t need to lock around sort, so long as the list has only primitive objects and no custom key function. Or, to avoid worrying about which operations are atomic, we can follow a simple rule: always lock around reads and writes of shared mutable state. After all, acquiring a threading.Lock in Python is cheap.

(Following this simple rule will also improve your code’s chances of running correctly in interpreters without a GIL, like Jython or IronPython, in which operations like list.sort are not atomic.)

Although the GIL does not excuse us from the need for locks, it does mean there is no need for fine-grained locking in CPython. In a free-threaded language like Java, programmers make an effort to lock shared data for the shortest time possible, to reduce thread contention and allow maximum parallelism. Since threads cannot run Python in parallel, however, there’s no advantage to fine-grained locking. So long as no thread holds a lock while it sleeps, does I/O, or some other GIL-dropping operation, you should use the coarsest, simplest locks possible. Other threads couldn’t have run in parallel anyway.

Use simple locks in Python.

Finishing Sooner With Concurrency #

I wager what you really came for is to optimize your programs with multi-threading. If your task will finish sooner by awaiting many network operations at once, then multiple threads help, even though only one of them can execute Python at a time. This is “concurrency”, and threads work nicely in this scenario.

This code runs faster with threads:

import threading

import requests

urls = [...]

def worker():

while True:

try:

url = urls.pop()

except IndexError:

break # Done.

requests.get(url)

for _ in range(10):

t = threading.Thread(target=worker)

t.start()

As we saw above, these threads drop the GIL while waiting for each socket operation involved in fetching a URL over HTTP, so they finish the work sooner than a single thread could.

Parallelism #

What if your task will finish sooner only by running Python code simultaneously? This kind of scaling is called “parallelism”, and the GIL prohibits it. You must use multiple processes. It can be more complicated than threading and requires more memory, but it will take advantage of multiple CPUs.

This example finishes sooner by forking 10 processes than it could with only one, because the processes run in parallel on several cores:

import os

import sys

nums = [1 for _ in range(1000000)]

chunk_size = len(nums) // 10

readers = []

while nums:

chunk, nums = nums[:chunk_size], nums[chunk_size:]

reader, writer = os.pipe()

if os.fork():

readers.append(reader) # Parent.

else:

# Child process.

subtotal = 0

# Intentionally slow code.

for i in chunk:

subtotal += i

print('subtotal %d' % subtotal)

# Send result to parent, and quit.

os.write(writer, str(subtotal).encode())

sys.exit(0)

# Parent.

total = 0

for reader in readers:

subtotal = int(os.read(reader, 1000).decode())

total += subtotal

print("Total: %d" % total)

This wouldn’t run faster with 10 threads than with one, because only one thread can execute Python at a time. But since it forks 10 processes, and each forked process has a separate GIL, this program can parcel the work out and run multiple computations at once.

(Jython and IronPython provide single-process parallelism but they are very far from full CPython compatibility. PyPy with Software Transactional Memory may some day be fast. Try these interpreters if you’re curious.)

Conclusion #

Now that you’ve opened the music box and seen the simple mechanism, you know all you need to write fast, thread-safe Python. Use threads for concurrent I/O, and processes for parallel computation. The principle is plain enough that you might not even need to write it on your hand!