How Buddhism Survived The Japanese Internment

Japanese Americans founded our practice, and they preserved and adapted it to life in the internment camps during World War II. Today we must adapt our practice in a crisis, are we up to the challenge?

A dharma talk I delivered to the Village Zendo by video, April 9, 2020.

Audio only:

Transcript #

Zen master Soen was traveling with his attendant.

This was in 1905, and the master, Soen Shaku, was 45 years old, and this was his second trip to America. On his first trip, Soen delivered the very first Zen talk ever delivered in English in North America, at the World Parliament of Religions which was part of the Chicago World’s Fair. But now, in 1905, Soen returned to America to lecture both to Japanese immigrant communities and to English speakers.

Soen had an attendant. His attendant was 29 years old, frail, kind of funny looking. He didn’t speak English. This attendant was an orphan and his story is very unclear. I’ve read many versions of this. His father maybe was a Russian man. He was born in Siberia to this unknown father and a Japanese mother. The father disappeared and the mother died, and the infant was discovered by a traveling Japanese monk beside his mother’s frozen body. The monk took him back to Japan and the boy was raised in a temple, and became a monk. His dharma name was Nyogen because of his foggy past. Nyogen means “like a dream.”

When Nyogen was 20 he came to Soen’s monastery, in Kamakura province. At the time, Nyogen was very sick with tuberculosis, and he asked Master Soen, “What if I die?”

Soen said, “If you die, just die.”

Master Soen traveled to San Francisco in 1905 to teach Zen, and he brought frail little Nyogen as his attendant. They stayed with a wealthy family of white benefactors, and Nyogen took a job as the houseboy. Nyogen was very earnest and hard-working, but he had no experience as a houseboy. He didn’t know how an American household was run. And he didn’t speak any English. So the family gave him five bucks and fired him. Nyogen packed up his suitcase and left.

Master Soen walked with him, and carried his suitcase for him. They passed through Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. There was a thick mist. Picture then this image, the famous, impressive Zen master and his misfit, half-breed attendant. The master carrying the servant’s suitcase.

Suddenly, Soen put down Nyogen’s suitcase. Soen said,

This may be better for you, instead of being my attendant. Just face this great city and see whether it conquers you or you conquer it.

He turned in the mist and left Nyogen, and they never saw each other again.

The year 1905 was a hard time to be a Japanese immigrant on the West Coast. In the previous couple of decades, Japanese people had immigrated to work as cheap labor at farms and factories. They formed a large community on the West Coast, and they called themselves “nikkei,” which is the term I’m going to use here.

Racism against nikkei was on the rise at this time. The year after Nyogen landed in San Francisco, the school board voted to segregate nikkei children. The year after that, the U.S. and Japan negotiated something called “The Gentleman’s Agreement,” in which the Japanese government banned emigration to the United States.

This racism against Japanese immigrants is going to escalate over the next couple of decades. There is a 1924 Congressional act that effectively bans all Asian immigration. And then we’re eventually going to get to Japanese internment. So stay tuned.

Nyogen, meanwhile—he’s broke, he’s homeless, he doesn’t speak any English, and his master has left for Japan. Nyogen took odd jobs as a porter, as a short-order cook, as a hotel manager. Meanwhile he taught himself English and he spent his spare time at the San Francisco Public Library, reading every book he could find either about Buddhism or about Western philosophy.

He began teaching Zen in the early 1920s, and he moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles around 1930. He called his temple “The Floating Zendo.” He taught meditation wherever he could, at a friend’s apartment or a rented space. There was no traditional temple, no fine robes or incense. People who came to learn from him just sat on battered folding chairs. This willingness to improvise is going to come in handy.

We know what’s coming now. The U.S. and Japan take opposing sides in World War II, and war between them seems likely. On December 7, 1941, the Japanese military bombs Pearl Harbor. The forced relocation and internment of all people of Japanese descent on the West Coast begins a few months later.

But the really extraordinary thing that I learned recently, is that after the Pearl Harbor attack, the government began to arrest Buddhist priests within hours. There was one priest of a Zen temple near Pearl Harbor—Pearl Harbor was attacked on a Sunday morning, and this priest was leading Sunday morning services when they heard the explosions outside. They didn’t know what they were but they decided to evacuate the temple. A few hours later, when the priest returned, the temple was surrounded by U.S. soldiers. They said, “Who are you and what are you doing?”

He said, “I’m coming back to feed the temple birds.”

They said that they were going to arrest him. He let out the birds so that they wouldn’t starve while he was gone. He let them fly out the window, and then the soldiers arrested him.

How could the government move that fast? For more than a decade, the FBI and the military had maintained a list of people they would arrest if and when war broke out with Japan. That list was primarily Japanese language teachers, martial arts instructors, and Shinto and Buddhist priests. Nikkei Christian ministers were exempted from this list. They were not considered threats to America.

I’m taking most of this talk from a book that came out last year, American Sutra by Duncan Ryuken Williams, about Buddhists during Japanese internment. I really recommend it. I also want to share some photos with you, mostly by Dorothea Lange. These were commissioned as propaganda by the War Relocation Authority, to show how humane the relocation was. Lange did not obey, though, and when they saw Lange’s photographs, they suppressed them. Most of the photos didn’t come out until 2006.

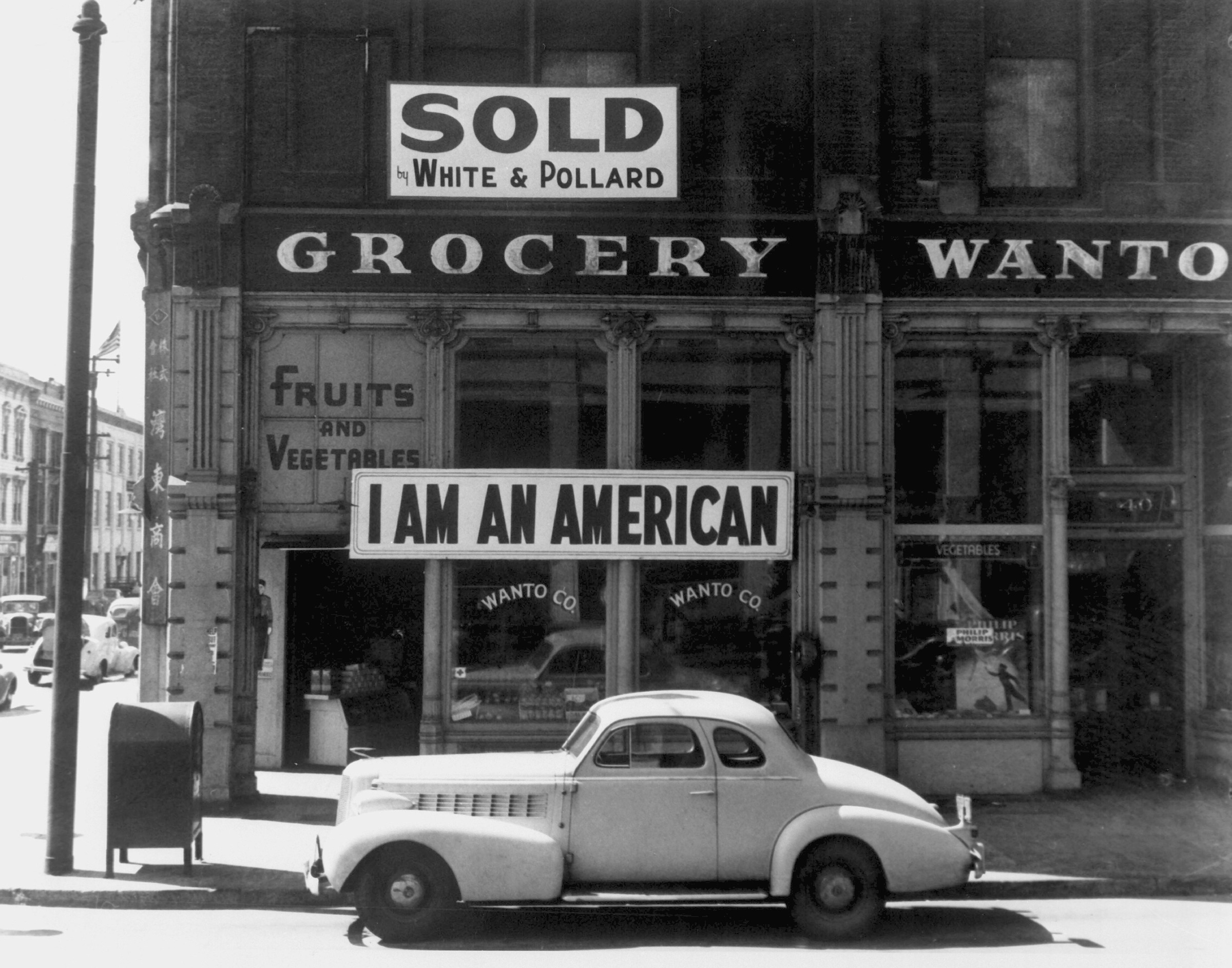

Japanese American Grocer. (Oakland, CA, March 1942. Dorothea Lange.)

Williams tells the following story about the Kimura family.

The Kimuras lived and farmed in California’s Central Valley near Fresno. Mr. and Mrs. Kimura were first-generation nikkei, and they had a 10-year-old daughter named Masumi. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Kimuras heard that all the priests of the Fresno Buddhist Temple had been arrested by the FBI, and that some white teenagers had shot up the door of the temple. Then at the even closer temple to them in a town called Madera, the FBI arrested the president of the temple board.

Mr. Kimura was very concerned, because he was on the Madera Buddhist Temple board himself. He thought that the FBI might show up at his door, and sure enough, three weeks after Pearl Harbor, they did. They didn’t arrest anybody that day, but they kept coming back over the next few weeks to ask more questions. Duncan Ryuken Williams writes:

Mr. Kimura decided to take steps to prove the family’s loyalty to America. One day shortly after that first FBI visit, his daughter Masumi was performing her daily chore of lighting the furnace next to their Japanese-style bathtub when Mr Kimura entered the room. He was carrying items he had found throughout the house that had Japanese language inscriptions or “Made in Japan” written on them. Among them were Masumi’s precious Hinamatsuri dolls, which had been given to her on Girl’s Day. As tears rolled down her cheeks, she watched him throw the dolls and all the other Japanese artifacts into the fire.

Her father did not burn everything, however. He could not bring himself to destroy the bound edition of Buddhist sutras that had been handed down through generations of the family. Instead, he asked his wife to find boxes and some Japanese kimono cloth while he went outside and dug a hole behind their garage with a backhoe. After wrapping the scriptures in the kimono cloth, he placed them in tin rice-cracker boxes, carefully lowered them into the hole, and covered them with dirt. By burying them next to the garage, he hoped to be able to find them at some later date.

The FBI never arrested Mr. Kimura, but the story gets worse anyway. In February 1942, FDR signs the executive order for the relocation and internment of all Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Two thirds of these people are American citizens.

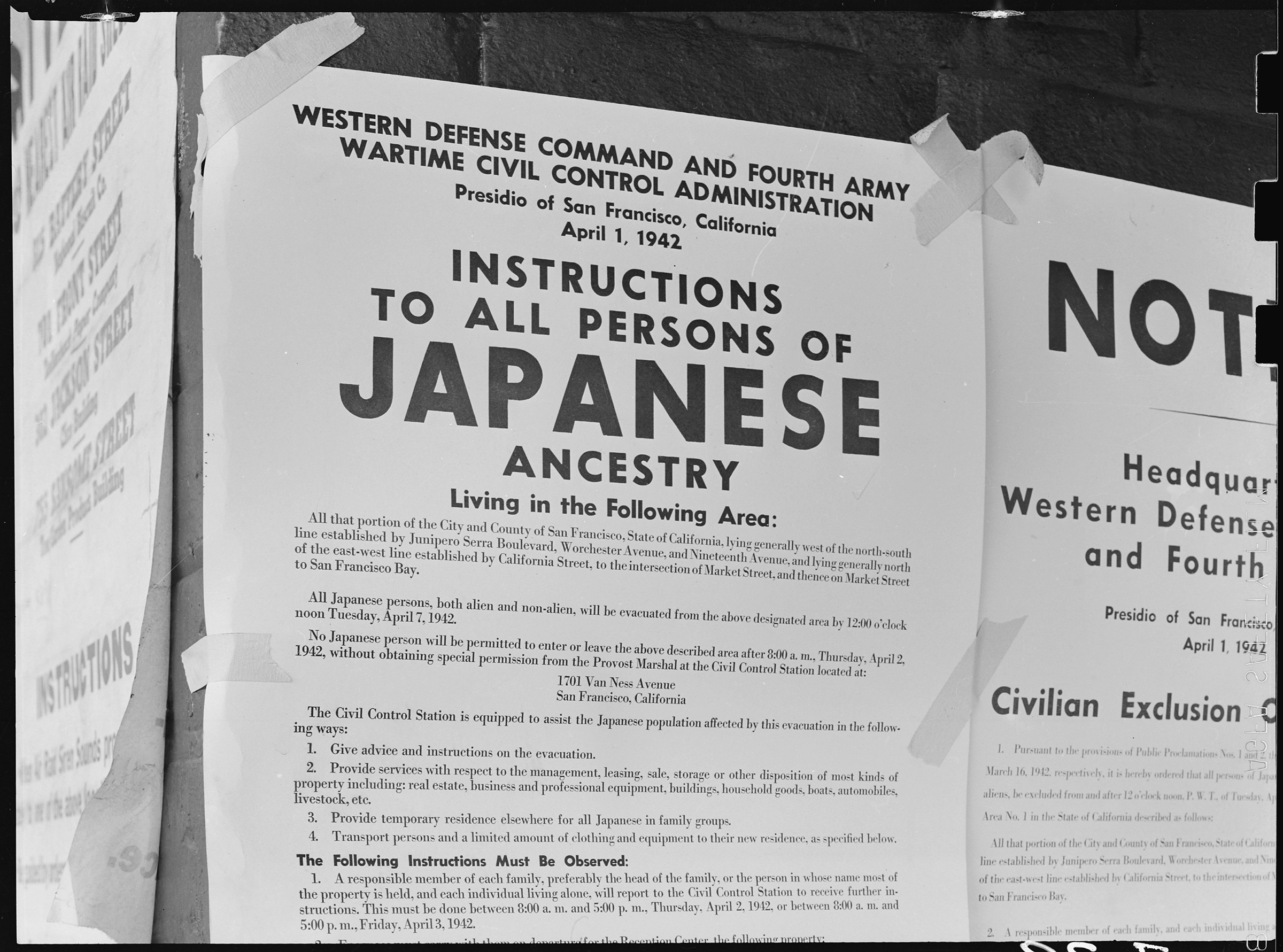

Posted Japanese American Exclusion Order. (San Francisco, CA, April 1942. War Relocation Authority.)

Waiting for Registration. (San Francisco, CA, 1942. Dorothea Lange.)

In April, the Kimura family was ordered to report to Fresno to be relocated. They had just a few days’ notice and they had to sell everything. They sold their farm for a twentieth of what they had originally bought it for. Just imagine the economic devastation that this causes. An immigrant family who has invested everything in this plot of land and it’s wiped out overnight.

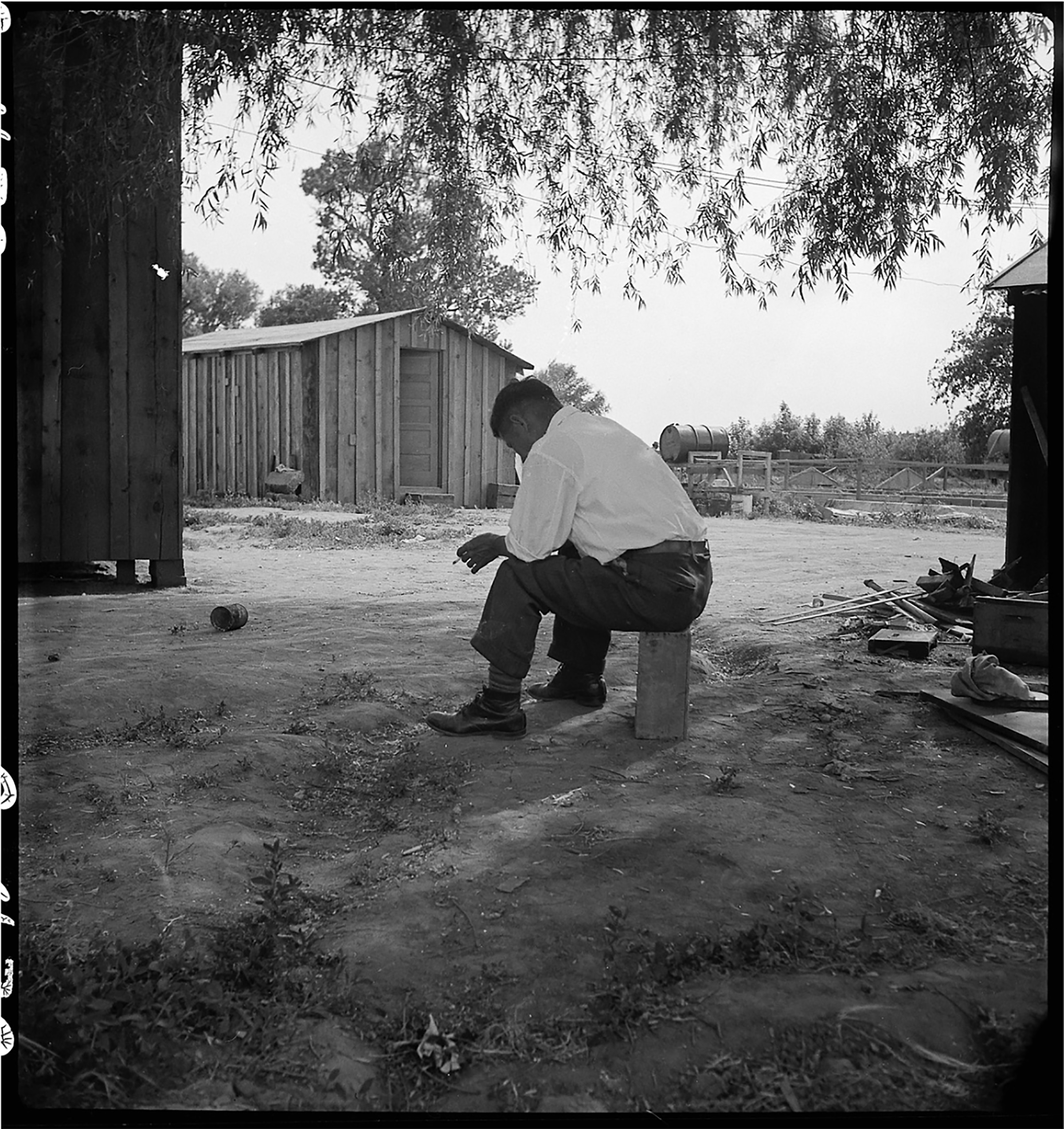

Tenant Farmer. (Woodland, CA, May 1942. Dorothea Lange.)

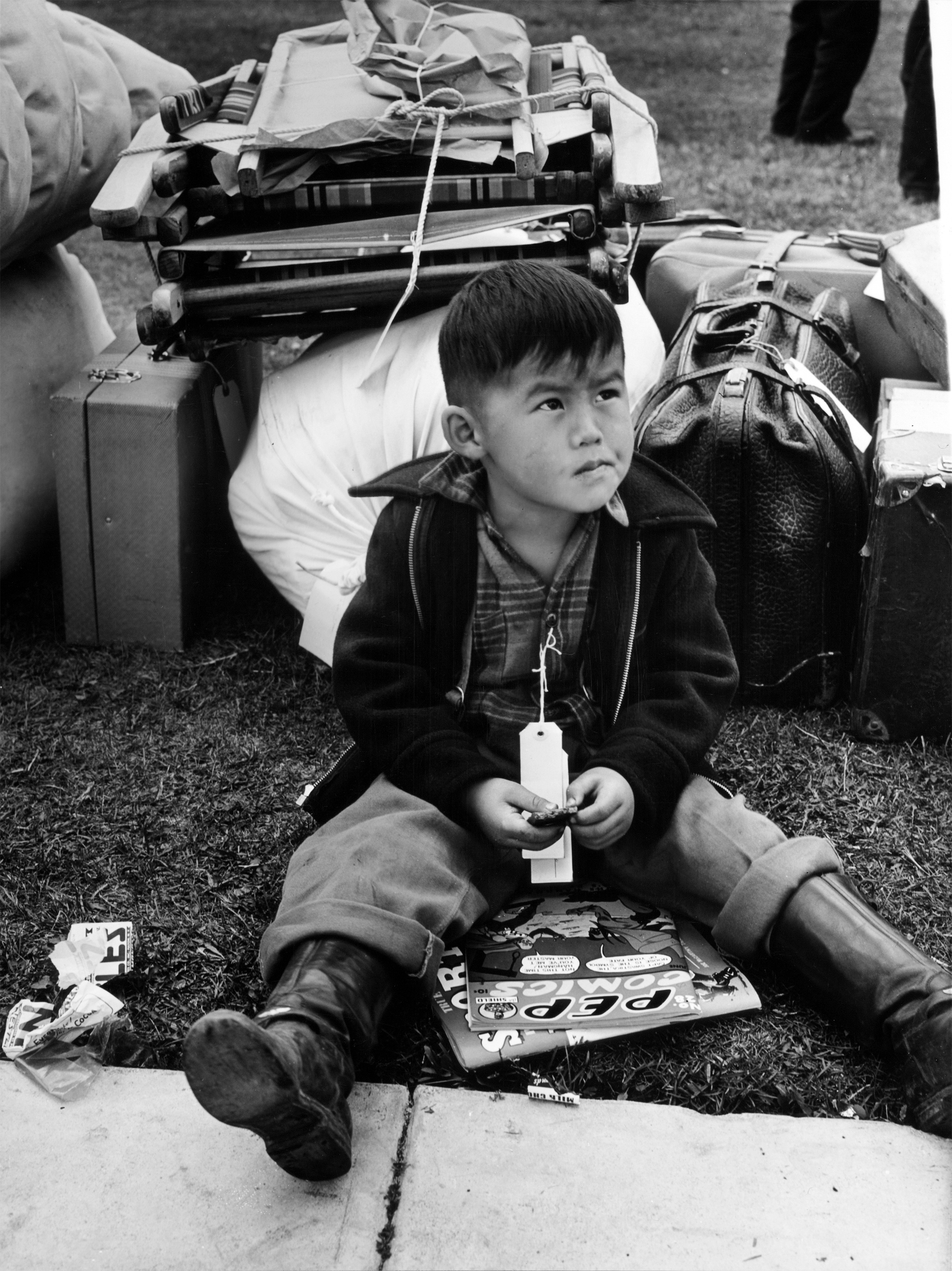

Tagged for Evacuation. (Salinas, CA, May 1942. Russell Lee.)

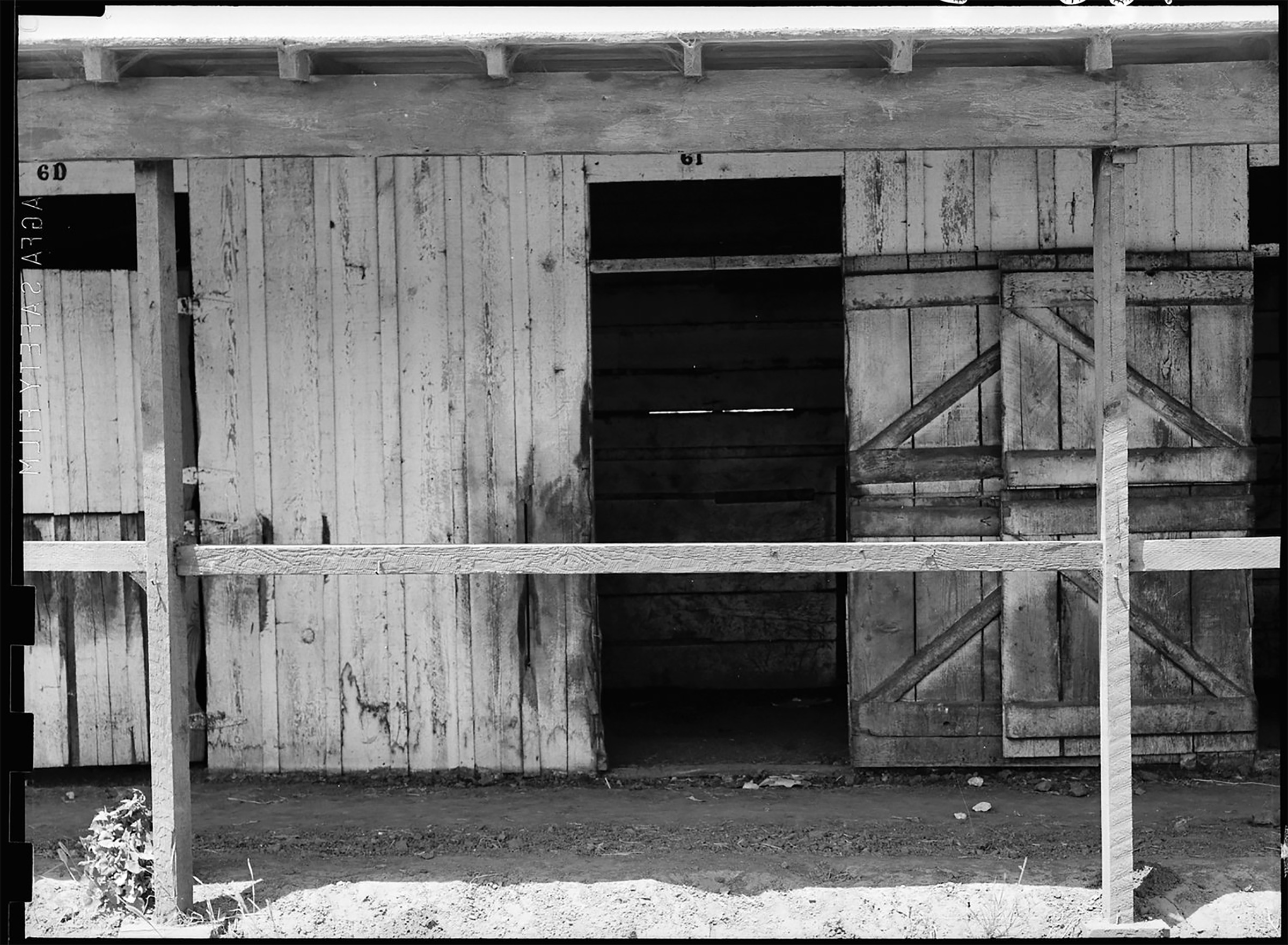

They packed one suitcase full of valuables and stored it at the Fresno temple for the duration of the war, and reported to the Fresno assembly center. They were housed in converted racehorse stalls that still stank of manure.

Horse Stall. (San Bruno, CA, June 1942. Dorothea Lange.)

Nyogen was living in Los Angeles when the relocation order came. He wrote the following poem:

Thus have I heard:

The army ordered

All Japanese faces to be evacuated

From the city of Los Angeles.

This homeless monk has nothing but a Japanese face.

He stayed here thirteen springs

Meditating with all faces

From all parts of the world,

And studied the teaching of Buddha with them.

Wherever he goes, he may form other groups

Inviting friends of all faces,

Beckoning them with the empty hands of Zen.

Japanese Buddhists of all kinds arrived at the camps with empty hands.

These were mostly Pure Land Buddhists, mostly of the Nishi Hongwanji sect. But there were also Shingon and Nichiren Buddhists, and Zen. They came with nothing—no robes, no bells, no incense, no altars. If they had brought Buddhist texts with them they were mostly confiscated. The camp authorities had been instructed to confiscate all Japanese-language material, with the exception of Bibles.

A woman named Hisa Aoki wrote in her journal:

Really, do white Americans think all they have to do is confiscate written matter, and the Japanese will completely forget how to read Japanese or completely obliterate the contents of what was written? How can you eliminate in one sweep what was absorbed into your blood, your flesh, your marrow? I want to shout at them—only if you turn the Japanese into ashes can you do that!

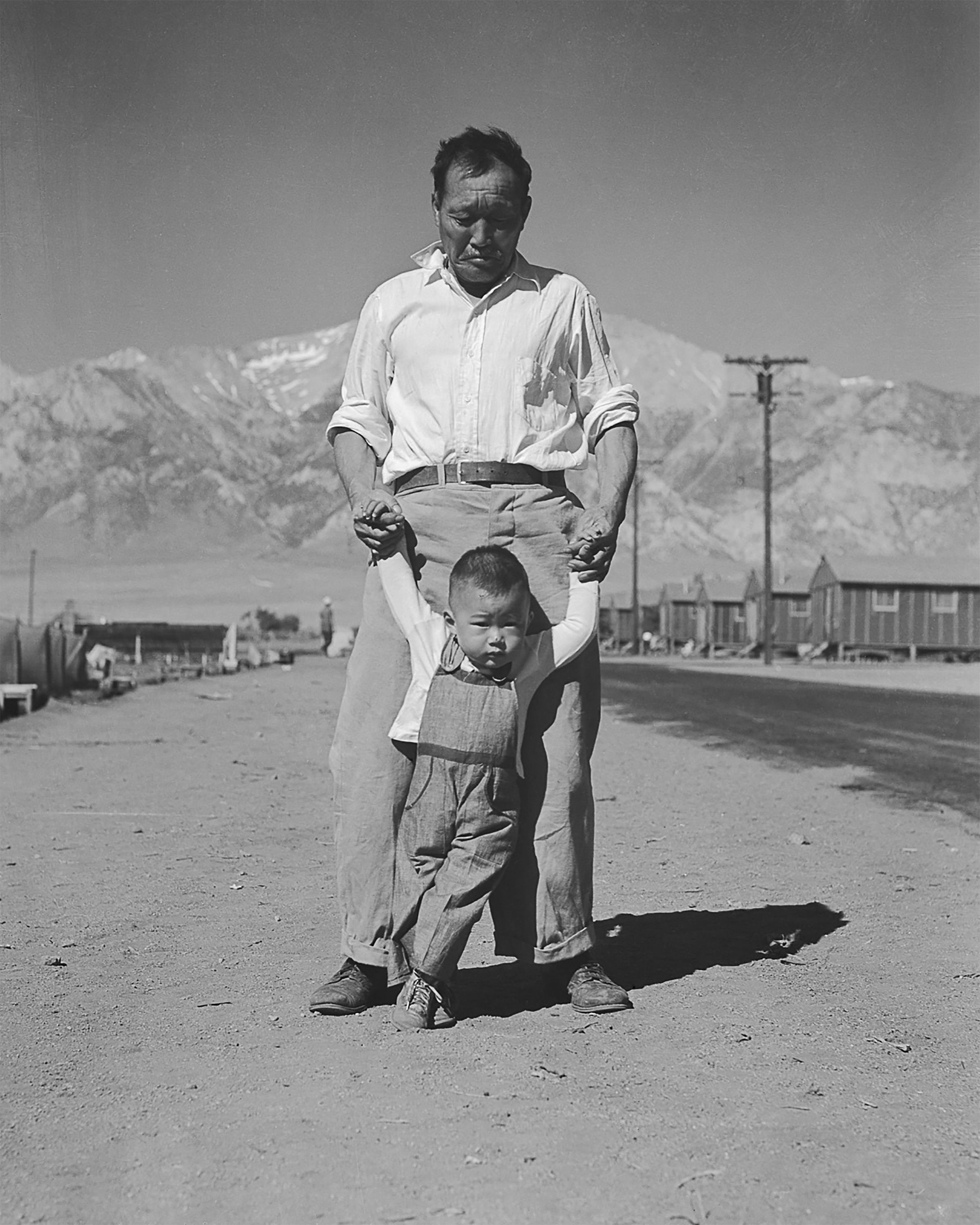

Buddhist study group at the Fresno assembly center. (1942. US Army Signal Corps.)

Buddha’s birthday is April 8th, and the first Buddha’s birthday celebration in the camps required a lot of invention. Traditionally for Buddha’s birthday, we have a little statue of Baby Buddha, and we pour sweet tea over it and surround it with flowers. But they didn’t have any of this. At a North Dakota internment camp, a man snuck a carrot from the kitchen and carved into a Baby Buddha, and the internees pooled their sugar rations to make sweet coffee to pour over it. At a camp in Wisconsin, they didn’t have any flowers so they dyed toilet paper red with beet juice and folded that into paper flowers.

Learning to Walk. (Manzanar, CA, 1942. Dorothea Lange.)

Nyogen was sent to Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming. He established what he called the Wyoming Zendo. He wrote:

Here in this room, twenty by twenty in size, I live with another family, parents and a daughter, and the visitors bring their own chairs or sit on the floor. Ten or twelve of them enjoy the tranquility of their contemplation. They are the happiest and most contented evacuees in this center.

The camp administrators were suspicious of Buddhism. Officially, the policy was that all religions are respected and permitted equally, but in practice sometimes, some Buddhist gatherings were shut down, or some Buddhists leaders were questioned and given loyalty tests. Some of the Buddhists in the camps thought the best strategy would be to abandon Buddhism, and maybe even convert to Christianity, to avoid any more suspicion, or any more questioning of their loyalty.

But there was a counter-movement called the Young Buddhist Association, which was led by second-generation nikkei. At a camp in Arizona, the Young Buddhist Association held a conference called “Gassho.” The keynote speech was from a Pure Land priest, Noboru Tsunoda. He said:

Buddhism in America is doomed. Such was the impression of many people following the outbreak of war and the resulting evacuation. … However, we find that the very opposite has taken place; the hardships and adversities of our faith in the Lord Buddha and His All-embracing Teachings and our experience in the relocation centers has shown more than clearly that religion does not consist of beautiful churches and hosts of clergymen, neither does it consist of dogma as set down by authorities; the fundamental basis of religion is in the strength of our faith.

When there’s a crisis like this, when people’s lives are turned upside down, they don’t go back to normal. They just keep transforming.

As the war between Japan and the United States came to an end in the summer of 1945, Japanese Americans were incrementally released from the camps. The West Coast towns that they returned to were not welcoming. There were newspaper editorials saying “all Japs should be deported.” There were stores that refused to sell to them. The Buddhist temples that had been locked up for the duration of the internment, almost all of them were broken into, looted, vandalized.

The Kimura family, after the war, returned to try to buy their farm back. The farm’s new owners asked for a price ten times what they’d paid the Kimuras. The Kimuras couldn’t afford that, so they gave up, and went to live with relatives in Los Angeles, and left their farm behind. The new owners had torn down the garage so there was no hope of locating where they had buried the sutras that had been in their family for generations. The Fresno Buddhist temple where they had stored their suitcase of valuables had been broken into, and the suitcase was gone. They lost everything.

Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. (Hayward, CA, May 1942. Dorothea Lange.)

Japanese Americans rebuilt, though. They restored their temples. For a while they were using them as hostels or as job centers, to get the returning evacuees on their feet again. The main Pure Land Buddhist school, called the Nishi Hongwanji, renamed itself the Buddhist Churches of America, and transformed itself into something that was more acceptable in America, something that could survive to this day. The nikkei had lost almost everything, but they rebuilt their farms and their businesses, and they found their place in America after the war.

I have told you such a tiny fraction of this story. I really recommend reading the book. I’ve had to skip the whole experience of Japanese American soldiers fighting in the U.S. military. They fought and they died in unbelievable numbers, with astonishing bravery, even while their loyalty was questioned, the military insulted their race and their religion, and their families were imprisoned in concentration camps. That story is the thing that I’m most sorry that I had to skip tonight. So I recommend reading the book.

I think that we should read about this time in history because this is our story. Our practice was founded in America by Japanese immigrants, and it’s because they preserved, protected, and adapted this practice during World War II that it survived in America. After the war, non-Japanese seekers, philosophers, poets, hippies, and beatniks came looking for somebody to teach them zazen. It’s out of the conversation between these seekers and Japanese American teachers—that transmission created the style of Zen that we practice at the Village Zendo.

We owe that generation of Buddhists an enormous debt, an unrepayable debt. But we can try to repay a little bit of it now, by preserving this practice, preserving it in this moment. They weathered confinement and economic devastation and the deaths of their loved ones, and they got through it. We can get through this. We don’t have all our altars and Buddhas and incense bowls right now. We can’t even get into one room and all chant in unison, and we can’t sit side-by-side in zazen. But, religion does not consist of this. It’s in the strength of our faith.

It happened that on the same day Japan surrendered, Nyogen’s camp in Wyoming was closed. He shut down the Wyoming zendo and returned to Los Angeles. An old student of his owned a hotel there and gave him a room to live in.

Nyogen wrote:

For forty years I have not seen

My teacher, Soen Shaku, in person.

I have carried his Zen in my empty fist

Wandering ever since in this strange land.

The cold rain purifies everything on the earth

In the great city of Los Angeles, today.

I open my fist and spread the fingers

At the street corner in the evening rush hour.