Reading A Journal of the Plague Year in New York

In New York City today, the streets are empty and the air pollution is clearing. During the plague outbreak of 1665, London’s streets, too, began reverting to a state of nature:

… the great Streets within the City, such as Leaden-hall-Street, Bishopgate-Street, Cornhill, and even the Exchange it self, had Grass growing in them, in several Places; neither Cart or Coach were seen in the Streets from Morning to Evening.

Reading Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, I see parallels with New York on every page. His stories are as eerie, and sometimes horrible, as New York’s current experience. But Defoe’s narrator makes a good companion these days for the lonely reader: swapping stories with a fellow veteran is a comfort.

Daniel Defoe was only five years old in 1665. Yet his Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722, is so obsessive and disordered it seems like he must have lived through the outbreak as an adult. Defoe’s narrator is a character based on his uncle, Henry Foe, and I suspect much of the book is taken from Henry Foe’s actual journal of that year. No novelist could invent an account so unhinged. The narrator circles again and again around a few stories and ideas, constantly inserting “as I have mention’d before”, “as I have observ’d above” into his sentences. There are no chapters or sections, no structure except the roughly chronological. There is little plot except the one we are living now: the first reports of the infection, the flight of the aristocrats, the exponential onslaught, the isolation of the middle class, the dangerous work of the poor.

This is not a well-written book. But it’s a conversation with someone who survived an epidemic, someone who understands, and that is the only kind of person I want to talk to.

At the onset of the virus in New York, my partner Jennifer and I considered fleeing. Out-of-state family and friends offered their homes to us for the duration. We hesitated until the decision was made for us: the White House advised anyone who escaped from New York to self-quarantine for 14 days, so we stayed put.

Defoe’s narrator “H. F.” also hesitates to leave London, while the news darkens and his brother begs him to evacuate. By the time H. F. decides, it’s too late:

For tho’ it is true, all the People did not go out of the City of London; yet I may venture to say, that in a manner all the Horses did; for there was hardly a Horse to be bought or hired in the whole City for some Weeks.

He prepares to leave on foot with a servant, but his servant quits. It’s a sign from God that H. F. should stay, and he takes the hint.

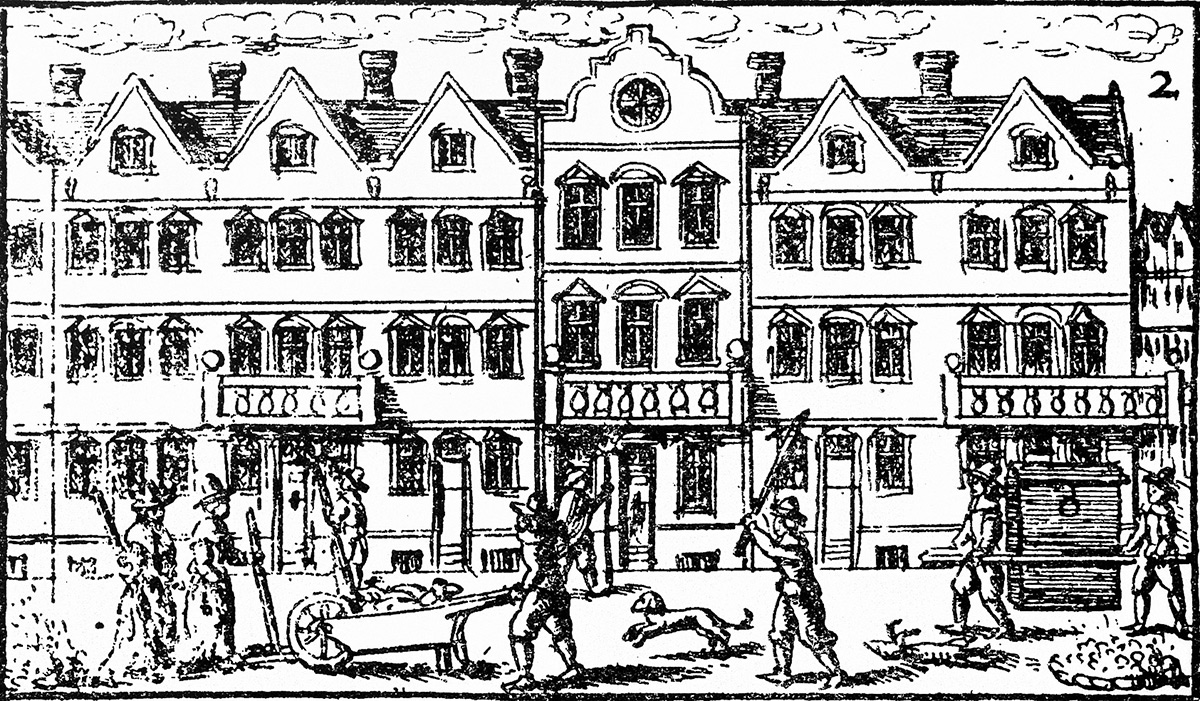

The London magistrates’ main defense against the plague was the “shutting up of houses”—when any member of a household became sick, their house was locked and a red cross painted on the door with the words “Lord have Mercy upon us”. Two watchmen guarded the house, one in the day and one at night; it was their duty both to keep its inhabitants inside, and to supply them with food and medicine, and to call a doctor or the Dead-Cart when needed.

New York has not enacted such paternalistic measures, but China has:

This contract is a pledge that we are not going to leave the house over the next 14 days. She also gave us plenty of information material about COVID-19 and then walked us home. Once at home, she put a seal on the door that would make it obvious if we left the house. 15/n pic.twitter.com/1Wvxbs2lI6

— Lukas Hensel (@LukasHenselEcon) March 19, 2020

Generally, China is a great country to be quarantined. The community actively supports us. For example, the community leader offered to bring our online orders to our door as delivery drivers are not allowed to enter communities at the moment (and take our trash out). 16/n

— Lukas Hensel (@LukasHenselEcon) March 19, 2020

In London, H. F. himself is briefly deputized to shut up houses, but the job is so repugnant to him that he quickly bribes his way out of it. On no point is H. F. more passionate than the injustice and uselessness of shutting up houses. This policy confines the well with the sick, likely dooming them to infection. Their sacrifice does not accomplish its purpose, for he suspects that the plague, like coronavirus, might be carried by those who seem well, making containment impossible. And besides, many households break out through stealth, bribery, or force. He hears that one family

blow’d up a Watchman with Gun-powder, and burnt the poor Fellow dreadfully, and while he made hidious Crys, and no Body would venture to come near to help him; the whole Family that were able to stir, got out at the Windows one Story high… After the Plague was abated they return’d, but as nothing cou’d be prov’d, so nothing could be done to them.

In New York, our unloved mayor inspires no confidence during the crisis. But in London, H. F. praises how “my Lord Mayor” and the aldermen manage the city’s response. Law and order are upheld for the most part, and bodies in the street are always carted away by the morning.1 Even at the plague’s peak, “Provisions were always to be had in full Plenty, and the Price not much rais’d neither”.

Although the food supply is intact in H. F.’s epidemic and ours, shopping for groceries is fraught.

It is true, People us’d all possible Precaution, when any one bought a Joint of Meat in the Market, they would not take it of the Butchers Hand, but take it off of the Hooks themselves. On the other Hand, the Butcher would not touch the Money, but have it put into a Pot full of Vinegar which he kept for that purpose.

While many open-air farmers markets remain open to provide New Yorkers with fresh goods from regional farmers, fishers and bakers, GrowNYC has ramped up safety measures to comply with social distancing guidelines. In order to safeguard the health and well-being of market visitors and staff, they’ve banned customers from handling produce (only gloved staff), suspended all sampling by vendors, supplied hand sanitizer at every market and barricaded most food from direct public access with plexiglass.

Despite our precautions, shopping is the most anxious activity in my weekly routine, and perhaps for good reason:

This Necessity of going out of our Houses to buy Provisions, was in a great Measure the Ruin of the whole City, for the People catch’d the Distemper, on those Occasions, one of another, and even the Provisions themselves were often tainted.

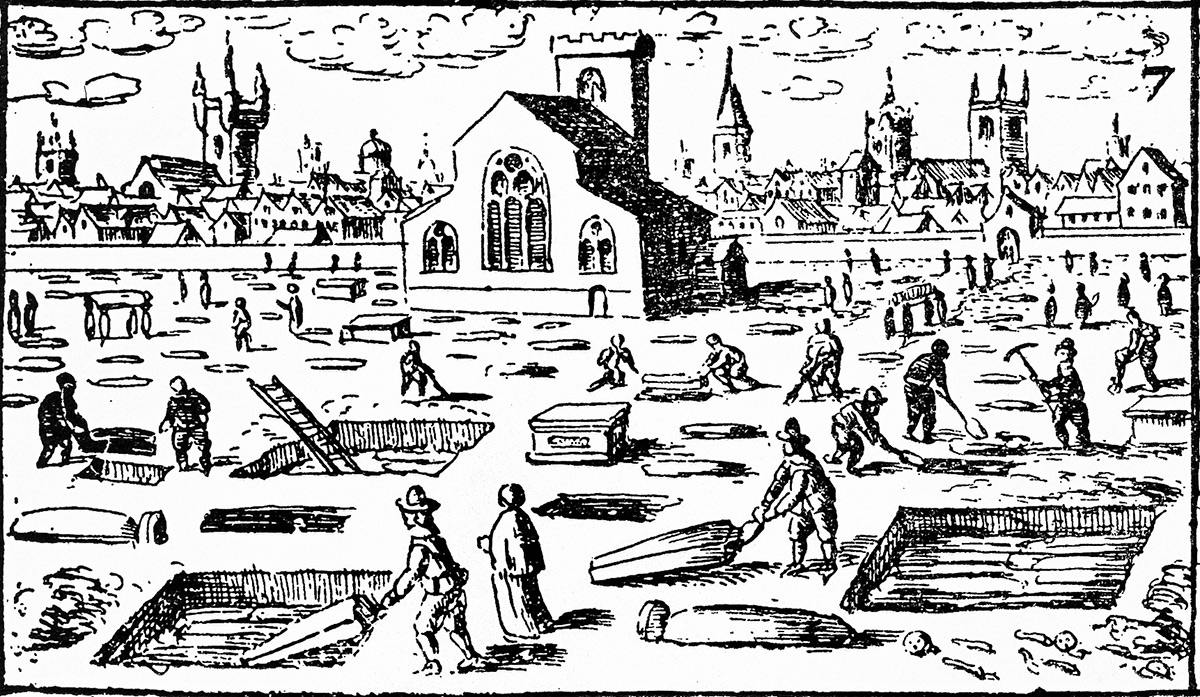

The Butchers took that Care, that if any Person dy’d in the Market, they had the Officers always at Hand, to take them up upon Hand-barrows, and carry them to the next Church-Yard.

To avoid shopping, New Yorkers seem determined to bake their way through the crisis. Stores’ stocks of flour are low, and yeast is always sold out. I’ve begun a sourdough starter and I bake two loaves a week. H. F. has the same idea:

I went and bought two Sacks of Meal, and for several Weeks, having an Oven, we baked all our own Bread; also I bought Malt, and brew’d as much Beer as all the Casks I had would hold.

In New York we are advised to keep six feet apart and wear face masks. In London they practice social distancing too:

Whether it were in the Street, or in the Fields, if we had seen any Body coming, it was a general Method to walk away.

Londoners in public carry herbal prophylactics in their mouths and pockets, especially once they learn about asymptomatic carriers who appear to be “sound”:

But when the Physicians assured us, that the Danger was as well from the Sound, that is the seemingly sound, as the Sick; and that those People, who thought themselves entirely free, were oftentimes the most fatal…. Then I say they began to be jealous of every Body, and a vast Number of People lock’d themselves up, so as not to come abroad into any Company at all, nor suffer any, that had been abroad in promiscuous Company, to come into their Houses, or near them; at least not so near them, as to be within the Reach of their Breath, or of any Smell from them; and when they were oblig’d to converse at a Distance with Strangers, they would always have Preservatives in their Mouths, and about their Cloths to repell and keep off the Infection.

The rich fled both cities at the onset. A friend of mine left New York by air, and he reported that first class was full but he had all of economy class to himself. The same in London:

Indeed nothing was to be seen but Waggons and Carts, with Goods, Women, Servants, Children, &c. Coaches fill’d with People of the better Sort, and Horsemen attending them, and all hurrying away.

A few merchant families sheltered in their ships on the Thames. A waterman tells H. F.:

All those Ships have Families on board, of their Merchants and Owners, and such like, who have lock’d themselves up, and live on board, close shut in, for fear of the Infection; and I tend on them to fetch Things for them, carry Letters, and do what is absolutely necessary, that they may not be obliged to come on Shore.

I have heard no such reports from New York, but David Geffen is enduring the crisis in his giant yacht off the Grenadines. He posted a sunset photo on Instagram with the message, “I’m hoping everybody is staying safe”.

Staying safe is possible for some middle-class Londoners:

Many Families foreseeing the Approach of the Distemper, laid up Stores of Provisions, sufficient for their whole Families, and shut themselves up, and that so entirely, that they were neither seen or heard of, till the Infection was quite ceased, and then came abroad Sound and Well.

But the poor must work, in London and New York:

Subway use has plummeted in recent weeks, but in poorer areas of New York City, many people are still riding. “I don’t want to get sick, I don’t want my family to get sick, but I still need to get to my job,” said Yolanda Encanción, a home health aide.

Daouda Ba, a 43-year-old immigrant from Senegal, sat hands tucked between his knees at the Burnside Avenue station. Mr. Ba lives in a nearby shelter, where he says more than 50 men share three bathrooms. On a recent morning, a friend had called with a small, paying job: Someone was moving out of their apartment and needed a hand. He sat waiting for the train to take him to Brooklyn, the rin-tin-tin of light rain hitting the metal awning.

“If I die, I die,” he said. 2

In London:

Where they could get Employment they push’d into any kind of Business, the most dangerous and the most liable to Infection; and if they were spoken to, their Answer would be, I must trust to God for that; if I am taken, then I am provided for, and there is an End of me, and the like: OR THUS, Why, What must I do? I can’t starve, I had as good have the Plague as perish for want.

H. F. fears the poor might form mobs, break into wealthy houses, and loot them:

But the Vigilance of the Lord Mayor, and such Magistrates as could be had, for some, even of the Aldermen were Dead, and some absent, prevented this; and they did it by the most kind and gentle Methods they could think of, as particularly by relieving the most desperate with Money, and putting others into Business, and particularly that Employment of watching Houses that were infected and shut up; and as the Number of these were very great, for it was said, there was at one Time, ten thousand Houses shut up, and every House had two Watchmen to guard it, viz. one by Night, and the other by Day; this gave Opportunity to employ a very great Number of poor Men at a Time.

In New York as well, the city has begun a jobs program related to the outbreak:

#JobAlert: @NYCHealthSystem is hiring 500 nonclinical staff and will expand to thousands soon.

— NYC Council Speaker Corey Johnson (@NYCSpeakerCoJo) April 12, 2020

Despite the great differences between H. F.’s London and my New York, and the different diseases attacking us, I mostly see the resemblance of our experiences. Our stories have the same plot, and the same characters: some are craven and selfish, some are brave and generous, most are just trying to make it through. Despite our isolation, we feel intensely our connection with each other and with people of all eras who lived in an epidemic.

Images: UK National Archive.

-

Samuel Pepys is less impressed with municipal services in his diary entry of August 22, 1665: “I went on a walk to Greenwich, on my way seeing a coffin with a dead body in it, dead of plague. It lay in an open yeard. … It was carried there last night, and the parish has not told anyone to bury it. This disease makes us more cruel to one another than we are to dogs.” ↩︎

-

Edited for space. Read the full, sad article on the New York Times. ↩︎