How To Write Resilient MongoDB Applications

Update: This technique has been superseded by MongoDB’s built-in retryable writes, introduced in 2017. Retryable writes are far simpler and superior to the techniques described here. For even stronger guarantees, use transactions, released in 2018.

Once, on a winter afternoon in early 2012, I met a MongoDB customer who was very angry.

He'd come to our regular "MongoDB Office Hours" at our office in Soho, and he had one question: "How can I make my application resilient in the face of network errors, outages, and other exceptions? Can I just retry every operation until it succeeds?" He demanded to know why we hadn't published a simple, smart strategy that would work for all applications.

This guy, I'll call him Ian, was upset, and I couldn't help him. My guilt has pressed the details of that day in my brain. We were sitting in a windowless room, the only free space we could talk in at our little office. There was a nasty fluorescent light overhead. We sat side by side on the edge of the table, because the room had no chairs. Ian had deep circles under his eyes, like he'd been up the night before worrying about this question. "How do I write resilient code?"

All I could tell Ian was, "We can't publish a strategy that deals with network errors and outages and command errors for you, because we don't know your application. There's a variety of operations you can do, and a variety of tradeoffs you can make between latency and reliability, between the risk of doing an operation twice versus not doing it at all. That's why we haven't tried to write a one-size-fits-all strategy. And even if we could, all the drivers act differently, so we'd have to publish a guide for every language."

I was not happy with my answer, and neither was Ian.

In the years since, I've worked to come up with a better answer. First I wrote the Server Discovery and Monitoring Spec, which all our drivers have now implemented. The spec vastly improves drivers' robustness in the face of network errors and server failovers. Complaints like Ian's are rarer now, because drivers throw exceptions more rarely. Additionally, all drivers now behave the same, and we validate their behavior with a standardized common test suite.

Second, I developed a technique called Black Pipe Testing so Ian can test how his code responds to network failures, command errors, or any other event while talking to MongoDB. Black Pipe Testing is convenient and deterministic; it makes error cases reproducible and easy to test.

Now it's possible to answer Ian. How would you answer him, if he came into our big office in Times Square today? What's a smart strategy for writing a resilient MongoDB application?

Your Challenge

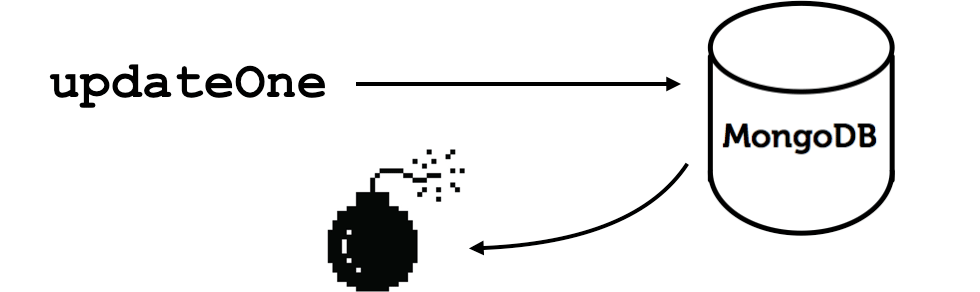

We're going to tell Ian how to do this updateOne resiliently:

updateOne({'_id': '2016-06-28'},

{'$inc': {'counter': 1}},

upsert=True)The operation counts the number of times an event occurred, by incrementing a field named "counter" in a document whose id is today's date. Pass "upsert=True" to create the document if this is the first event today.

What Can Go Wrong

Transient errors

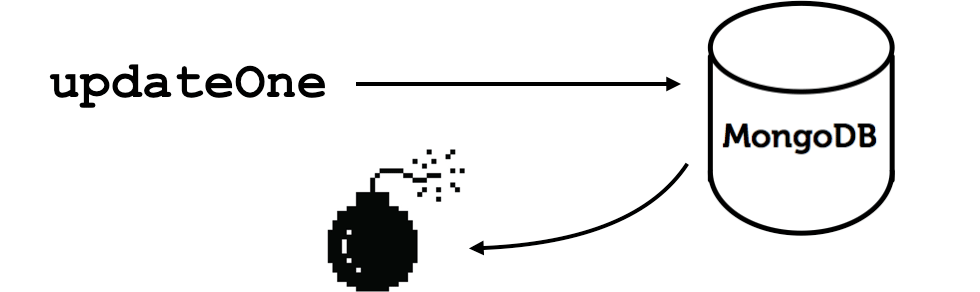

When Ian sends his updateOne message to MongoDB, the driver may see a transient error from the network layer, such as a TCP reset or a timeout.

Transient Network Error, Failover, or Stepdown

The driver cannot tell if the server received the message or not, so Ian doesn't know whether his counter was incremented.

There are other transient errors that look the same as a network blip. If the primary server goes down, the driver gets a network error the next time it tries to send it a message. This error is brief, since the replica set elects a new primary in a couple seconds. Similarly, if the primary server steps down (it's still functioning but it has resigned its primary role) it closes all connections. The next time the driver sends a message to the server it thought was primary, it gets a network error or a "not master" reply from the server.

In all cases, the driver throws a connection error into Ian's application.

Persistent errors

There might also be a lasting network outage. When the driver first detects this problem it looks like a blip: the driver sends a message and can't read the response.

Persistent Network Outage

Again, Ian cannot tell whether the server received the message and incremented the counter or not.

What distinguishes a blip from an outage is that attempting the operation again will only get Ian another network error. But he doesn't know that until he tries.

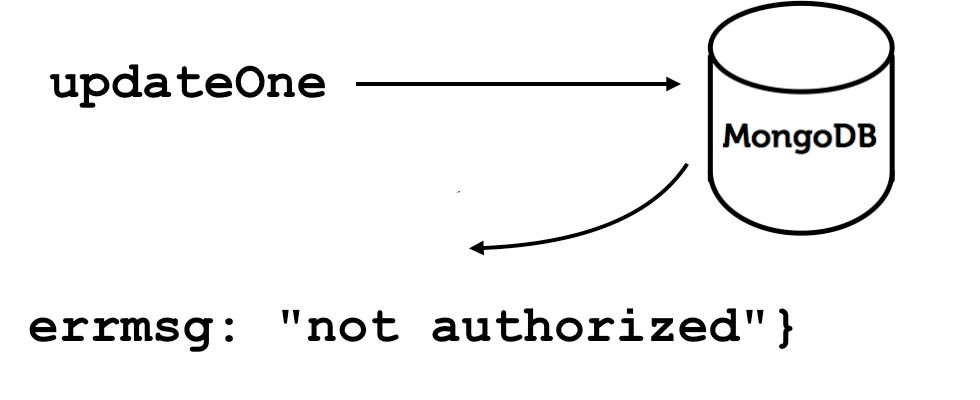

Command errors

When the driver sends a message, MongoDB might return a specific error, saying that the command was received but it could not be executed. Perhaps the command was misformatted, the server is out of disk space, or Ian's application isn't authorized.

Command Error

So, there are three errors that are not entirely distinguishable and require different responses from Ian's code. What single smart strategy can you give Ian to make his application resilient?

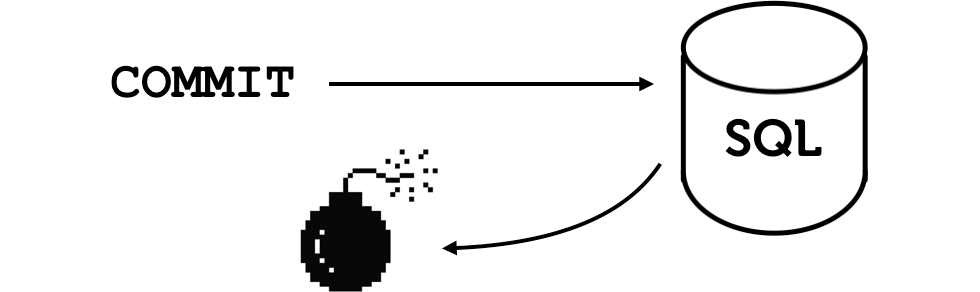

Is It Because We Don't Have Transactions?

You may wonder whether this is specific to MongoDB because it doesn't have transactions. Consider if Ian used a traditional SQL server. He opens a transaction, updates a row, and sends the COMMIT message. Then there's a network blip. He cannot read the confirmation from the server. Does he know whether the transaction has been committed or not?

Doing an operation exactly once with a SQL server has the same problems as doing it with a non-transactional server like MongoDB.

How Do MongoDB Drivers Handle Errors?

To formulate your smart strategy, you need to know how MongoDB drivers themselves respond to different kinds of errors.

The Server Discovery and Monitoring Spec requires a MongoDB driver to track the state of each server it's connected to. For example, it might represent a 3-node replica set like:

- Server 1: Primary

- Server 2: Secondary

- Server 3: Secondary

This data structure is called the "topology description". If there's a network error while talking to a server, the driver sets that server's type to "Unknown", then throws an exception. Now the topology description is:

- Server 1: Unknown

- Server 2: Secondary

- Server 3: Secondary

The operation Ian was attempting is not retried automatically; however, the next operation blocks while the driver works to rediscover the primary. It re-checks each server twice per second for up to 30 seconds, until it reconnects to the primary or detects that a new primary was elected. These days MongoDB elections only take a second or two and the driver discovers the outcome of the election about half a second after that.

If there's a persistent outage, on the other hand, then after the 30 seconds are up the driver throws a "server selection timeout".

In the case of a command error, what the driver thinks about the server hasn't changed: if the server was a primary or a secondary, it still is. Thus the driver does not change the state of the server in its topology description, it just throws the exception.

(To learn more about the Server Discovery and Monitoring Spec, read my article Server Discovery And Monitoring In PyMongo, Perl, And C, or watch my presentation from last year's MongoDB World 2015 called "MongoDB Drivers and High Availability: A Deep Dive". There I talk in detail about the data structures described in the spec and how the spec tells drivers to respond to errors. That's a great background for this article about resilient applications.)

Bad Retry Strategies

I've seen a few.

Don't retry

The default is to not retry at all. This strategy fails in one of the three error cases.

| Transient network err | Persistent outage | Command error |

| May undercount | Correct | Correct |

In the case of a transient network error, Ian sends the message to the server and doesn't know if the server received it. If it did not, the event is never counted. His code logs the error, perhaps, and moves on.

Interestingly, in the face of a long-term network outage or a command error, "don't retry" is the correct strategy because these are non-transient errors that cannot be profitably retried.

Always retry

Some programmers write code that retries any failed operation five times or, if they really care about resilience, ten times. I've seen this in a number of production applications.

i = 0

while True:

try:

do_operation()

break

except network error:

i += 1

if i == MAX_RETRY_COUNT:

throwLast year I talked with a Rackspace engineer named Sam. He'd inherited a Python codebase that applied this bad strategy: it just retried over and over whenever it received any kind of exception.

Sam could see that this was dumb. He noticed that I'd recently rewritten PyMongo's client code in terms of the Server Discovery and Monitoring Spec, and he suspected he could take better advantage of the more robust new driver. There was a smarter retry strategy out there but he didn't know exactly what it was. In fact, it was from my conversation with Sam that this article was born.

What did Sam see? Why shouldn't Ian retry every operation five or ten times?

| Transient network err | Persistent outage | Command error |

| May overcount | Wastes time | Wastes time |

In the case of a network blip, Ian no longer risks undercounting. Now he risks overcounting, because if the server read his first updateOne message before he got a network error, then the second updateOne message increments the counter a second time.

During a persistent outage, on the other hand, retrying more than once wastes time. After the first network error, the driver marks the primary server "unknown"; when Ian retries the operation, it blocks while the driver attempts to reconnect, checking twice per second for 30 seconds. If all that effort within the driver code hasn't succeeded, then trying again from Ian's code, reentering the driver's retry loop, is fruitless. It causes queueing and latency in his application for no good reason.

The same goes for a command error: if Ian's application isn't authorized, retrying five times does not change that.

Retry network errors once

Now we're close to a smart strategy. After his initial operation fails with a network error, Ian does not know if the error is transient or persistent, so he retries the operation just once. That single retry enters the driver's 30-second retry loop. If the network error persists for 30 seconds, it's likely to last longer, so Ian gives up.

In the face of a command error, however, he does not retry at all.

| Transient network err | Persistent outage | Command error |

| May overcount | Correct | Correct |

So we've only got one red square left—how can Ian avert the possibility of overcounts?

Retry network errors, make ops idempotent

Idempotent operations are those which have the same outcome whether you do them once or multiple times. If Ian makes all his operations idempotent, he can safely retry them without danger of overcounting or any other kind of incorrect data from sending the message twice.

| Transient network err | Persistent outage | Command error |

| Correct | Correct | Correct |

So how should Ian make his updateOne message idempotent?

Idempotent operations

MongoDB has four kinds of operations: find, insert, delete, and update. The first three are easy to make idempotent; let us deal with them first.

Find

Queries are naturally idempotent.

try:

doc = findOne()

except network err:

doc = findOne()Retrieving a document twice is just as good as retrieving it once.

Insert

A bit harder than queries, but not too bad.

doc = {_id: ObjectId(), ...}

try:

insertOne(doc)

except network err:

try:

insertOne(doc)

except DuplicateKeyError:

pass # first try worked

throwThe first step in this pseudo-Python generates a unique id on the client side. MongoDB's ObjectIds are designed for this kind of usage, but any unique value will do.

Now, Ian tries to insert the document. If it fails with a network error, he tries again. If the second attempt fails with a duplicate key error from the server, then the first attempt succeeded, he'd merely been unable to read the server response because of the error from the network layer. If anything else goes wrong, he cancels the operation and throws an exception.

This insert is idempotent. The only warning is, I have assumed Ian has no unique index on the collection besides the one on _id that MongoDB automatically creates. If there are other unique indexes, then he must parse the duplicate key error: if it was on some other index that might signify a bug in his application.

Delete

If Ian deletes one document using a unique value for the key, then doing it twice is just the same as doing it once.

try:

deleteOne({'key': uniqueValue})

except network err:

deleteOne({'key': uniqueValue})If the first is executed but Ian gets a network exception and tries it again, then the second delete is a no-op; it just won't match any documents. This delete is safe to retry.

Deleting many documents is even easier:

try:

deleteMany({...})

except network err:

deleteMany({...})If Ian deletes all the documents matching a filter, and his code gets a network error, then he can safely try again. Whether the deleteOne runs once or twice, the result is the same: all matching documents are deleted.

In both cases there is a race condition: another process might insert matching documents between the two attempts at deleting them. But the race is no worse than if his code weren't retrying.

Update

So what about updates? Let's ease into it, by first considering the kind of update that is naturally idempotent.

# Idempotent update.

updateOne({ '_id': '2016-06-28'},

{'$set':{'sunny': True}},

upsert=True)This is not the same as our original example; here Ian isn't incrementing a counter, he's setting today's "sunny" field to True to cheer himself up. Saying that today is sunny twice is just as good as saying it's sunny once. In this case the updateOne is safe to retry.

The general principle is that there are some MongoDB update operators that are idempotent,

and some that aren't. $set is idempotent,

because if you set something to the same value twice it makes no difference,

whereas $inc, which was our original example,

is not idempotent.

If Ian's update operators are idempotent then he can retry them very easily: he tries once, and if he gets a network exception he tries again. Simple.

try:

updateOne({' _id': '2016-06-28'},

{'$set':{'sunny': True}},

upsert=True)

except network err:

try again, if that fails throwSo now we're finally ready to attack our hardest example, the original non-idempotent updateOne:

updateOne({ '_id': '2016-06-28'},

{'$inc': {'counter': 1}},

upsert=True)If Ian does this twice by accident, he increments the counter by 2.

How do we make this into an idempotent operation? We're going to split it into two steps. Each will be idempotent, and by transforming this into a pair of idempotent operations we'll make it safe to retry.

To begin, let us say the document's counter value is N:

{

_id: '2016-06-28',

counter: N

}In Step One, Ian leaves N alone, he just adds a token to a "pending" array. He needs something unique to go here; an ObjectId does nicely:

oid = ObjectId()

try:

updateOne({ '_id': '2016-06-28'},

{'$addToSet': {'pending': oid}},

upsert=True)

except network err:

try again, then throw$addToSet is one of the idempotent operators. If it runs twice, the token is added only once to the array. Now the document looks like this:

{

_id: '2016-06-28',

counter: N,

pending: [ ObjectId("...") ]

}For Step Two, with a single message Ian queries for the document by its _id and its pending token, deletes the pending token, and increments the counter.

try:

# Search for the document by _id and pending token.

updateOne({'_id': '2016-06-28',

'pending': oid},

{'$pull': {'pending': oid},

'$inc': {'counter': 1}},

upsert=False)

except network err:

try again, then throwAll MongoDB updates, whether they are idempotent or not, are atomic: a single updateOne either completely succeeds or has no effect at all. So if the token is removed from the pending array, then and only then is the counter is incremented by one.

Taken as a whole, this updateOne is idempotent. Imagine Ian pulls the token out of the array and increments the counter on his first try, but but then he fails to read the server response, because there's a network error. His second try is no-op because the query looks for a document with the pending token but he's already pulled it out.

So Ian can safely retry this updateOne. Whether it's executed once or twice, the document ends up the same:

{

_id: '2016-06-28',

counter: N + 1,

pending: [ ]

}Mission accomplished?

Now you've done it: you took Ian's original updateOne that was not safe to retry and made it idempotent by splitting it into two steps.

There are a few caveats to this technique. One of them is that Ian's simple increment operation now needs two round-trips. It requires double the latency and double the load. If the events he's counting are ok to undercount or overcount once in a blue moon when his friend trips over a network cable, he shouldn't use this technique.

The other caveat is, he will need a nightly cleanup process. Consider: what happens if this second step never completes?:

try:

updateOne({'_id': '2016-06-28',

'pending': oid},

{'$pull': {'pending': oid},

'$inc': {'counter': 1}},

upsert=False)

except network err:

try again, then throwSay there's a network outage that begins after Ian adds the pending token, but before he can remove it and increment the counter. The document is left in this state:

{

_id: '2016-06-28',

counter: N,

pending: [ ObjectId("...") ]

}Ian needs a nightly task to find any pending tokens left over from today's aborted tasks and finish updating the counter from them. To avoid concurrency problems, he waits until the end of the day, so there are no more processes updating the document with today's count. His task uses an aggregation pipeline to find documents with pending tokens, and adds the number of them to the current count:

pipeline = [{

'$match':

{'pending.0': {'$exists': True}}

}, {

'$project': {

'counter': {

'$add': [

'$counter',

{'$size': '$pending'}

]

}

}

}]

for doc in collection.aggregate(pipeline):

collection.updateOne(

{ '_id': doc._id},

{ '$set': {'counter': doc.counter},

'$unset': {'pending': True}

})For each aggregation result this task updates the source document with the final counter value, and clears the pending array by unsetting it.

The updateOne is safe to retry, because it uses the idempotent operators $set and $unset. Ian's cleanup task can keep trying it until it succeeds

no matter how flaky his network is.

With this cleanup task installed,

Ian's count of events for today will be eventually correct.

If Ian accepts these caveats—an increment requires two round trips, and may not be completed until the end of the day—then for very high-value operations this technique is a resilient way to increment his counter exactly once.

Testing for Resilience

We have a strategy for Ian, but he's still unhappy. How is he going to test that he's implemented it correctly throughout his code? I have a technique that I call "Black Pipe Testing".

When we test an application as a black box, we give it input and out pops the result, like toast. But these black box tests can't cause network failures, timeouts, outages, or command errors. Mocking at the network layer would be better, but if the network layer itself has bugs then mocking it out just masks those bugs.

Instead, I've come up with an idea I call "black pipe testing". It uses a real network server that speaks the MongoDB Wire Protocol. Ian connects his application to this server the same as he'd connect to MongoDB. But unlike MongoDB, Ian can tell this server to hang up, time out, or behave however he needs at the precise moment required to test every corner of his new error-handling logic.

My black pipe testing series includes articles and code to guide Ian. It provides everything he needs to test whether he's applied this strategy correctly.

A Smart Strategy

We've finally given Ian an answer. There is a strategy he can employ throughout his application. It correctly responds to transient network errors, outages, and command failures. It's effective and efficient, and a lot simpler than we might have feared.