Review of "Autotools: A Practitioner's Guide"

My colleague Amalia Hawkins and I are choosing interns for our project this summer: a new Lua driver for MongoDB. Looking over their resumes I have to chuckle. Kid, you're 20 years old, you're not proficient in C, C++, Java, Javascript, and PHP. Maybe you did some homework in a language and you know some syntax, but it does not make you "proficient." I am proficient in one language: Python. It took me a decade.

When I began learning Python as a professional, what I didn't know that I didn't know was how to maintain a cross-platform open-source package like PyMongo. I didn't know how to write source code compatible with Python 2 and 3. I didn't know all the grotty little details about individual Python versions. I didn't know, for example, that assigning to a threadlocal isn't thread-safe in Python 2.6. I did not know how to design Python C extensions to run in mod_wsgi sub interpreters. I did not know that Python 2.7's unittest framework introduced assertRaisesRegexp and that it was reintroduced to Python 3.1 as assertRaisesRegex without the "p", then backported to Python 2.6 via unittest2, again without the "p". I did not know how to make a package installable on Linux, Mac, and Windows, with and without a C compiler.

I tell you this, not to brag about what I have learned—although to be honest I am proud of how far I have come. I just want to explain how high my standards for "proficient" have risen, as a result of my experiences working on PyMongo.

Now that I am taking over libbson and libmongoc, the C libraries for MongoDB client applications, I am humbled by how much I do not know. I am even more humbled by the unknown unknowns. I expect they are primarily in the distribution tools, not the language. After all, I "learned C" in college—or so I thought when I was 20 years old. But all I learned was its syntax. What I did not learn was how to maintain a cross-platform open-source distribution in C. So when I was charged with becoming an expert C programmer, I did not pick up a book on syntax or algorithms. I looked for a book on the Autotools.

Autotools: A Practioner's Guide to GNU Autoconf, Automake, and Libtool, by John Calcote, seems virtually the only modern book on the subject. Compared to all the C++ books out there, or all the "Learn C in 21 Days"-type introductions to the language, there is very little written about the Autotools. But a huge proportion of open source software for Linux and Unix uses the Autotools for packaging and distribution. Becoming an expert open source C programmer requires enough familiarity with the Autotools to create distributions and debug problems in them.

Calcote's book tackles this tiresome subject in a stylishly written and carefully organized manner.

We get off to a bumpy start, however. Calcote must begin by listing the parts of the Rube Goldberg device: primarily Automake, Autoconf, and Libtool. But there are wheels within wheels, like autom4te, aclocal, and a whole gearbox of little-known cogs. We barely understand the purpose of the Autotools, so we read the list of parts without understanding their functions. It is discouraging at the outset. But you will be alright if you just read the chapter once, do your best, then soldier on ignorantly and hope to muddle through.

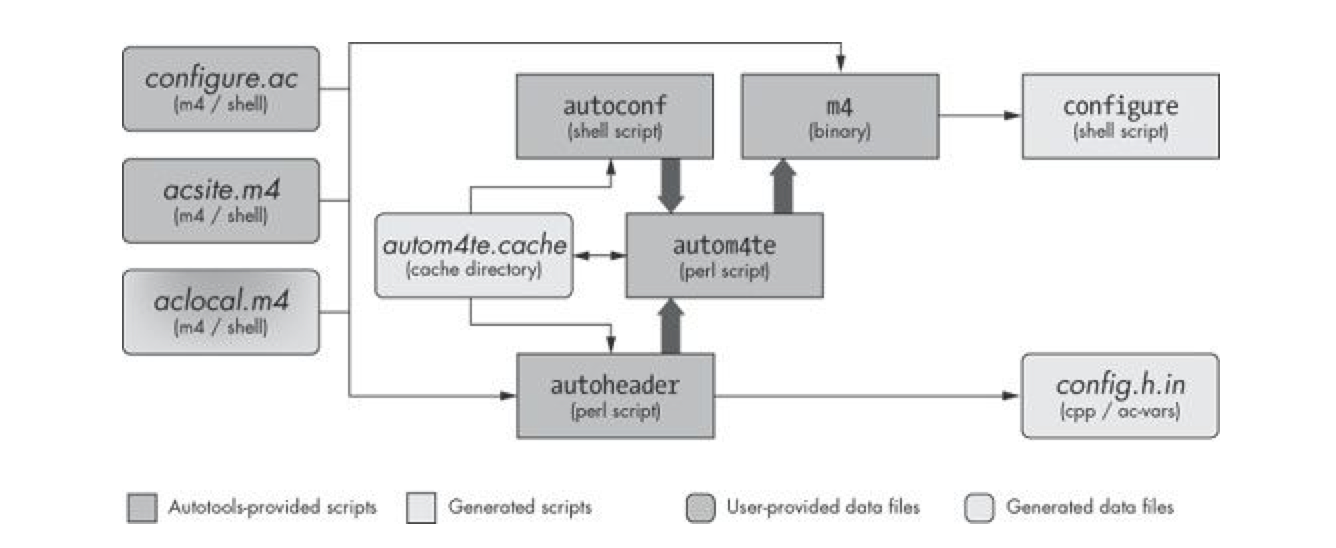

It only gets more disheartening when we come to the data-flow diagrams:

Data can flow in so many directions among the Autotools that the diagrams, although we desperately want them, are almost meaningless: every file depends on all the others, it seems, and the scripts all call each other. The system is so complex you need to read much of the book before the diagrams in Chapter One can make sense. Indeed, I have read the whole book, then reread the first chapter, and I still do not understand it. But the round trip brings a bit more clarity, and more hope.

The next chapters are tractable, since they explain the contraption one gear at a time, beginning at the lowest-level tools and working backwards from there. Due to the Autotools' design-by-accretion, each chapter discusses a tool, like make, and the script it executes, like Makefile, and then the tool that generates that script from a higher-level script. As we climb the levels of script-generating scripts we arrive, gasping, at the pinnacle: Automake. Except, of course, that the levels are not so cleanly separated at all, but are incomprehensibly intertwined. Calcote makes a heroic effort to focus each chapter on a specific aspect of the toolkit, but by necessity refers upwards and downwards, in the same way the tools themselves do.

In Chapters Eight and Nine, Calcote describes the monstrous undertaking of converting a large project from hand-written Makefiles to the Autotools. Here I skimmed quickly, but my admiration deepened for the author's patience. If I am ever willing to make such an expedition myself, I will want Calcote beside me. As A. E. Housman put it:

It will do good to heart and head

When your soul is in my soul's stead;

And I will friend you, if I may,

In the dark and cloudy day.

The last two chapters best fit the archetype of a "missing manual" for the Autools. In Chapter Ten, Calcote teaches us to use the M4 macro language in the context of Autoconf. I had recently been frustrated Googling for something as simple as this: How to execute one M4 expression if a symbol is defined, and another expression if not. The main trouble is that the M4 Manual teaches you to use raw M4, and the Autoconf Manual tells you that it has renamed all of M4's macros, so there is no one place on the Internet that actually tells you how to write Autoconf scripts. Calcote's explanation suffices to get you unstuck.

The final chapter, "A Catalog of Tips and Reusable Solutions," is without apology a bunch of facts that washed to the end of the book without coming to rest in any of the tutorial chapters. Yet the short sections here are more worthwhile than a "catalog" might promise. The opening bit on "Keeping Private Details out of Public Interfaces" teaches you enough about designing stable C APIs to keep you safe until you read David R. Hanson's C Interfaces and Implementations. Later, the section on cross-compilation collects crucial details, not just for people who actually cross-compile libraries, but for maintainers like me who must ensure their libraries are truly portable.

"Autotools: A Practitioner's Guide" is not fun to read, most likely. You read it when you must, and on that day it is indispensable. Calcote completes a tough job with honor and style, and his book testifies to his years of honest effort.