Review: Timestamp as a Service, not an Oracle

Timestamp as a Service, not an Oracle, by authors from Alibaba Cloud, in Proceedings of VLDB this year. Watch my presentation to the Distributed Systems Reading Group above, or read my summary below.

Timestamp Oracles #

Priestess of Delphi (1891) by John Collier.

An oracle is someone who speaks for a god and reveals divine knowledge. In computer science we’ve used “oracle” to refer to theoretical machines that could do something impossible, like solve the halting problem or produce truly random numbers. Also, for some reason, real actual machines that produce monotonic timestamps are called “timestamp oracles”.

A timestamp oracle is used by a distributed database to get monotonically increasing IDs, for ordering events. It’s a single server in your data center which provides a larger number every time you ask it. The timestamp might or might not be related to the wall clock.

- Why not Lamport clocks or vector clocks? They require you to pass these clock values between clients and servers, through all the layers of your multi-tier architecture. I know personally that database users find that burdensome.

- Why not synchronized clocks? Syncing clocks is hard, and no matter how precise the clock is, you need to add some latency to wait out the uncertainty. Well-synced clocks are becoming widely available, though; see Huygens and AWS Time Sync.

The paper mentions that timestamp oracles are used by various distributed systems: PolarDB-X, OceanBase, CORFU, TiDB placement driver, Percolator, Postgres-XL. I’ve only heard of half of these. The TiDB placement driver (“TiDB-PD”) includes a timestamp oracle in its implementation, and it’s the main example that this paper’s authors use as a comparison for evaluating their alternative.

Timestamp oracles only work for one data center. The timestamp consumers should be on a very low-latency link to the timestamp oracle server; cross-DC links are too slow for practical use. This paper doesn’t try to solve that problem: this paper’s timestamp-as-a-service is also intended for one data center.

A fault-tolerant timestamp oracle is a consensus group: each new timestamp is majority-committed. If the leader fails, the next leader must know the highest timestamp that the previous leader produced. The paper mentions that this can be optimized: the leader could reserve a range of timestamps. It majority-commits the range, and it gives out timestamps until the range is exhausted. A new leader reserves a higher range of timestamps than any previous one.

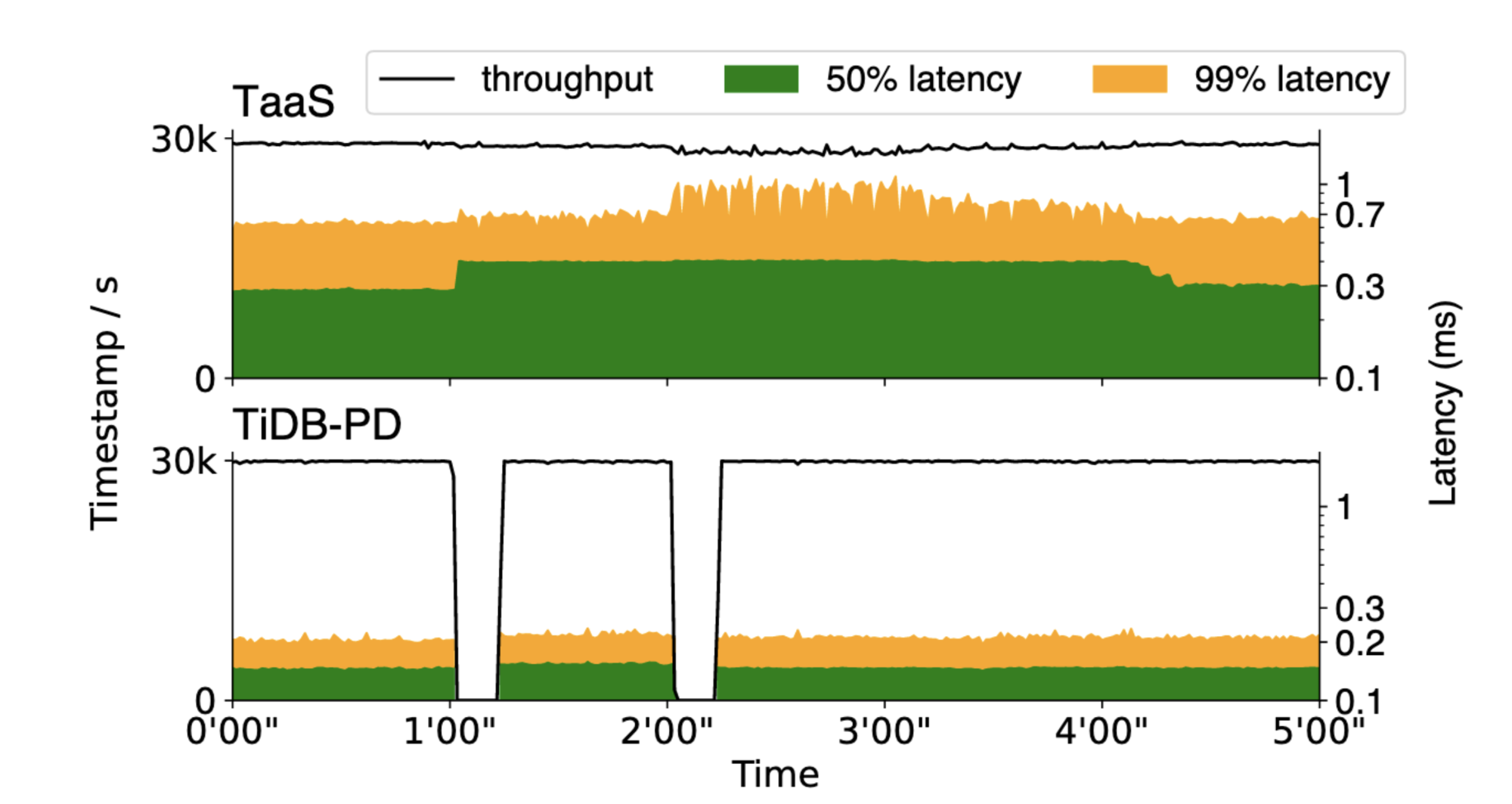

A consensus group is fault-tolerant, but nevertheless, losing the leader causes some brief unavailability. Especially since this consensus group must use timed leader leases, for speed and consistency. Therefore the new leader has to wait for the previous lease to expire. The paper shows that TiDB-PD is unavailable for 10 seconds after the leader dies. The black throughput line drops to zero each time the leader is killed:

Figure 9 from the paper, lower half

Besides being a single point of failure, the leader is a bottleneck—you can’t get timestamps from followers, so a system could saturate the timestamp oracle leader.

A Service, Not An Oracle #

The authors propose a timestamp service, rather than an oracle. They say an oracle is one server, therefore a single point of failure, even if it’s the leader of a consensus group. A service, however, is not a single point of failure. I don’t know if everyone agrees with these definitions of oracle and service, but it’s a useful distinction for this paper. The paper says a Timestamp-as-a-Service is “a distributed algorithm that computes logical timestamps from a consensusless cluster of clocks.” That means no unavailability from loss of the leader, and no bottleneck on the leader. Consensuslessness is not only fun to say, it’s the funnest part of this paper!

The Algorithm, 1.0 #

The paper presents the Timestamp-as-a-Service (TaaS) algorithm in two stages, starting with a simplified version that assumes no server failures or message loss. There can be any number of clients, and N servers.

A client starts a session S by sending the bottom timestamp ⊥ to all servers. The paper generally uses σ (sigma) for a session but I’m going to use S because I don’t read Greek. That symbol for “bottom timestamp”, you could think of it as negative infinity. Whenever you see that symbol you know you’re probably in the world of lattices and order theory and abstract algebra.

A “session” in this paper is not a sequence of database commands. It’s just the commands required to get one timestamp, then the session is over. The client gets its timestamp and then forgets everything, no state persists into the next session. So the client always starts its session by sending ⊥, even if it got a timestamp in a previous session.

Each server has a persistent timestamp, which is somehow initialized to some value when the server is born. When the server receives the client request, it increments its timestamp and sends its new current timestamp back to the client. Thus if a server replies with “5”, the client knows the server’s current timestamp is 5, and it knows the server had a timestamp less than 5 before the client talked to it. This will be important.

The session is complete once all servers have replied. The client uses the Mth‑smallest timestamp from the replies, for some M ≤ N. All clients must use the same M.

M can be anything! M should be the smallest majority, so if N is 5 then M should be 3. The paper starts abstractly, by showing TaaS is correct for any M from 1 to N. Eventually it admits that for maximum fault tolerance, M should be the smallest majority, same as a quorum in Paxos or any consensus algorithm. But for now, M is any number 1 through N.

Let’s look at an example of TaaS 1.0 in action.

Figure 2 from the paper.

There are Clients V and Client W, and Servers X, Y, and Z. Session Alpha starts concurrently with Session Beta. Session Gamma starts after Session Alpha. Let’s say M = 2, so at the end of each session the client chooses the second‑smallest timestamp from all the server replies.

Session Alpha gets timestamp 1, Beta gets timestamp 2, and Gamma gets timestamp 3. Beta’s allowed to have any timestamp since it’s concurrent with the others. So you can see these timestamps uphold the linearizability guarantee. The important constraint is, Session Alpha’s timestamp must be less than Session Gamma’s, and it is: 1 is less than 3.

The client could send its messages to all servers in parallel, or any order within a session, and the latencies could be of any length, TaaS still works.

Theorem 1 #

“The timestamp for session T is guaranteed larger than the timestamp for any session S that ended before T began.”

This sounds like a linearizability guarantee, and I believe you could call the timestamp a linearizable data structure. Proof:

- The Mth‑smallest response in S ≤ the Mth‑smallest server state at the end of S. (Servers’ timestamps increase monotonically, so their timestamps at the end of S must be ≥ their responses in S.)

- The Mth‑smallest server state at the end of S ≤ the Mth‑smallest server state at the start of T. (Monotonicity, and S ends before T starts.)

- The Mth‑smallest server state at the start of T < the Mth‑smallest response in T. (The client makes all the servers increment their timestamps during T.)

So by transitivity, the left side of #1 < the right side of #3. Q.E.D.

The Algorithm, 2.0 #

In the second and final version of TaaS, servers can crash-fail indefinitely, and they can come back online.

A restarted server still guarantees monotonicity, i.e. it remembers the last timestamp it produced before it crashed. The only way to guarantee this is some sort of replication.The paper suggests using RAID, or cloud storage like S3 which has its own replication, or make each timestamp server a consensus group with fault-tolerance. You might ask, if we make each timestamp server a consensus group, haven’t we come full-circle to the “timestamp oracle” that the paper says is bad? Not quite: now we have a separate group for each timestamp server, so if one group loses its leader, TaaS can proceed with the other groups without waiting for a new leader.

The TaaS client’s goal is to find a timestamp t such that:

- t > Mth‑smallest of all servers’ timestamps when the session started

- t ≤ Mth‑smallest of all servers’ timestamps when the session ends

These two properties are the two facts that Theorem 1 depends on.

Here’s an example where Server X is partitioned from the client. Let’s say M=2; we want the 2nd‑smallest timestamp.

From Figure 3.

The client remembers that it got timestamp 5 in some past session from Server X. This memory is a new feature of the fault-tolerant version of TaaS.

In session δ, the client gets a 4 and a 5 from the servers it can reach. It picks 5 as the timestamp for this session, because the client knows, without talking to Server X:

- 5 > 2nd-smallest timestamp at the start of the session: The client heard Servers Y and Z respond with timestamps 4 and 5, so their previous timestamps were less than 5.

- 5 ≤ 2nd-smallest timestamp at the end of the session: The client knows Servers X and Z now have timestamps at least 5.

The two facts that Theorem 1 relies on are both true, so the client can pick 5 without talking to Server X.

From Figure 3.

In session ε the client gets 5 and 6 from the servers it can reach. Now it doesn’t know the second‑smallest timestamp. If Server X is talking to some other client, it might have advanced to 7; then the second‑smallest would be 6. Or Server X might be at timestamp 5.5—timestamps don’t have to be integers! (I wish the paper had mentioned this earlier.) If Server X has 5.5, then 5.5 would be the second‑smallest. We don’t know. What’s the solution?

The client does something new now. Instead of sending the bottom timestamp to all the servers, like it did before, it continues this session. It thinks 6 might be the second‑smallest timestamp. So it sends 6 to any servers that might have less than 6: Server Y. Then Server Y updates its own timestamp to at least 6, increments it by one, and returns it.

Now the client has 6 from Z, 7 from Y. X is still down, but the client doesn’t care, it can choose 6:

- 6 > 2nd-smallest timestamp at the start of the session: The client heard Servers Y and Z respond with 5 and 6, so they started with less than 6.

- 6 ≤ 2nd-smallest timestamp at the end of the session: The client eventually heard Servers Z and Y respond with 6 and 7, they ended with at least 6.

So the client achieved certainty by advancing one of the server’s timestamps. That’s a specific example, here’s the general algorithm.

Algorithm 2.0 pseudocode #

The paper uses a pseudocode that’s hard for me to read, so of course I’ll make my own pseudocode that seems easier to me but may be worse for you. Sorry.

// global map from server to timestamp, initially bottom timestamp for

// all servers. the client persistently tracks this.

cache = {server: ⟘ for server in servers}

// client code to acquire one timestamp

def do_session():

// "session" is like "cache" but reset with top timestamp each session

session = {server: ⟙ for server in servers}

// like TaaS 1.0, initially send bottom timestamp to all servers

send timestamp ⟘ to all servers

while true:

reply = await next reply

// update global cache with max per server, local with min

cache[reply.server] = max(cache[reply.server], reply.timestamp)

session[reply.server] = min(session[reply.server], reply.timestamp)

if we received at least M replies:

candidate = Mth-smallest value in session

if candidate ≤ Mth-smallest value in cache:

return candidate

else if no more quickly-available replies:

// promote the candidate

for server in servers:

if cache[server] < candidate:

send candidate timestamp to server

As the client gets replies, it updates the global and local maps. The purpose of these two maps is to determine when we know the two facts we need for Theorem 1.

Each server’s timestamp is guaranteed to increase monotonically, but a client could get replies out of order. So it uses max when updating the global cache, to ignore delayed messages. The client uses min when updating the per-session map called session. I don’t understand why; it seems that if the client got a 6 from Server X, then a 5, it should keep the 6, because it knows that 5 is a delayed message. The algorithm is still correct, it just has unnecessary retries.

How does the client know when it’s acquired a correct timestamp, at the return timestamp line? Remember, the goal is to find a timestamp t such that:

- t > Mth‑smallest of all servers’ timestamps when the session started: at least M servers started < candidate, according to session-local map

- t ≤ Mth‑smallest of all servers’ timestamps when the session ends: at least M servers end > candidate, according to global map

The client knows candidate satisfies the first criterion, because according to the session-local map, there are M servers that had smaller timestamps when the session started, before the client talked to them. All the values in the session-local map are values that servers incremented during the session, so the starting values were smaller.

The client knows candidate meets the second criterion because it explicitly checks it in the global cache. The client hasn’t talked to all the servers, but it’s talked to enough of them to know that this fact is true. It wants to ensure that future sessions are guaranteed to get a larger timestamp than this one, and it’s learned enough to guarantee that.

If the client has no candidate, it tries to make the second criterion true by advancing the timestamps on servers that might have less than candidate. The client tries all lagging servers, including those that were unavailable recently, in case they came back online.

At the line, else if no more quickly-available replies, there’s some timeout while the client waits to see if the remaining servers are going to reply soon or not. I guess that’s a tunable parameter.

What Should M Be? #

It’s finally time to descend from lofty abstraction and decide a value for M. The authors write, “The system allows at most min(N − M, N − 1) downs while continuing its service.” So for optimal fault-tolerance M should be the median of 1 .. N:

I suppose it’s theoretically interesting that M could be any number, but practically, it should be a majority, which makes this protocol resemble consensus a lot. However, the authors insist this isn’t consensus, because servers never talk with each other. TaaS is a “bipartite architecture”, where clients and servers talk to each other, but servers don’t talk to servers and clients don’t talk to clients. There’s a nice little discussion in Section 6.2 of the definition of consensus and consensusless consistency.

Unique Timestamps #

Concurrent sessions may get the same timestamp. Solution: each server appends its server ID to the returned timestamp.

Their Evaluation #

Comparing TaaS to a consensus-based timestamp oracle (TiDB-PD), the authors claim:

- In the happy case, TaaS is higher-latency than TiDB-PD, especially with more servers.

- TiDB-PD stalls for 10 seconds after leader failure.

- TaaS latency doesn’t increase much when servers are slow or dead, if a majority is healthy.

Thus TaaS is closer to constant work, which makes it more stable as part of a whole system and avoids metastable failures. Here’s Figure 9 again, now with TaaS included:

At the 1- and 2-minute marks, the authors killed a server. TiDB-PD suffered a complete stall in throughput, TaaS merely increased latency a bit.

My Evaluation #

The algorithm is fairly simple, but the authors explain it with needlessly weird notation. These are three pieces of notation actually used in this paper:

This looks less like math and more like an alien language. The one on the bottom means the “second‑smallest timestamp received by session delta.” I guess that’s ok, but they never explain why delta gets an upside-down hat? Is that a rule in this alien culture?

More seriously, I’m curious about several questions:

- TaaS doesn’t assume timestamps are integers. If it did, i.e. if there were a minimum increment amount, could the fault-tolerant algorithm be more efficient?

- What happens when a client restarts and loses its long-lived global cache? Does that weaken fault-tolerance?

- What about reconfiguration?: how are timestamps servers initialized, added, or removed?

- Has Alibaba deployed this? It seems like they haven’t. Why?—did they use synced clocks instead?

I enjoyed this paper, and spent a long time understanding it (as you can see). It describes a new protocol in the classic distributed systems style. It provides rigorous explanations and proofs, and informative experiments. If you need monotonic ids within one data center and you can’t use synchronized clocks, TaaS is a simple solution with stable performance during failures.

Update: One of the authors has answered some of my questions about the protocol.